Some 15 years ago, Bee and I decided to sell up and commit to a voyaging life. It was an easy decision, taking just 4 months from decision, to selling the house, to moving aboard.

During that time we hunted around, rejected various boats—usually because they required far too much work, and we wanted to sail, not build—until we found one that seemed to suit us. We made an offer, more than we wanted to spend but much less than any of the rebuilds would finally have cost, had it accepted, and moved aboard.

I mentioned what we had done to a guy I worked with. He was probably 20+ years younger than me, had spent a number of years in the boat industry, and he proceeded to question me closely:

“Do you have an EPIRB? Do you have a watermaker? Do you have a forward-facing echo sounder?”

“No”, I replied.

“Well”, he said dismissively, “you can’t go cruising…”

70,000 Miles Later

However, we did go cruising and, some 70,000 miles later, we still do not possess any of those items he deemed necessary. Rather than fit out a boat for a lifestyle we had no idea we would like, we simply opted to try the lifestyle and then see what we might need to make things better.

The answer is surprisingly little, despite what the magazines and pundits would tell you. In fact, little has changed on the boat since we left Southampton: the original Garmin 128 GPS and the NASA Navtex still work, but we have replaced the depthsounder. After 9 years we added a secondhand radar and an AIS receiver.

A Less-Trodden Path

The first couple of years were hard as we learnt to slow down from a working life and, more importantly, learned to appreciate being in each other’s company for 24 hours a day, but we got better at it. And, whilst we have not sailed around the world, we haven’t languished in the Caribbean either.

So this post is about a less-trodden path for “wannabes” that is, I think, still valid in this world of the “consumer cruising” approach to all things marine. I am at a loss to understand why folks buy a boat, then spend thousands making changes whilst using up the one thing they can’t replace: their lives. Perhaps if the boat requires so much time and money it’s the wrong boat?

Hannah

We chose an 8-year-old, 36′ ferro-cement gaff ketch. The reasons were numerous, but principally, if you’re on a small budget, ferro boats offer a lot of advantages. Yes I know that the armchair pundits will tell you not to touch them, but I doubt ANY of those naysayers have ever owned one. Sure some can be dogs to look at, but you can see that and leave that one alone…find another one.

We paid UK£34,000 (US$47,000) for Hannah and that was a high price for a ferro boat. But the quality of workmanship, the storage and space, and the amount of practical gear on board meant we had little left to do but go sailing.

We liked the owners, found them open with us (and have remained friends since). The surveyor we chose had been party to putting the hull builder out of business in a legal case. He (the surveyor) spent a long time on the boat, charged accordingly, and still managed to get things wrong. But we talked it through with the sellers, offered less than the asking price, and have never regretted the decision.

We kept everything simple:

- Tiller steering.

- Manual windlass.

- Big cleats.

- No electric this or hydraulic that.

- No pressurized water.

- No refrigeration.

Result: no huge list of repairs, no shopping list from the chandlers, and certainly not years spent attempting to bullet-proof a boat to deal with the vagaries of the sea. Life is too short.

Gaff Rig

Gaffers are not so common on the cruising scene but are a wonderful way of crossing oceans with a minimum amount of money. They tend to be long-keeled, so track well; lend themselves to wind-vane self-steerers; heave-to well; and are pretty comfortable in big, ugly seas.

They also have negative qualities: that deep forefoot makes tacking in any sort of sea difficult, and going to windward is a lesson in patience—”like a cow in a bog”, according to John Illingworth.

Also, in a gaffer light winds mean slow speeds and possibly long passages. Sure, sometimes we wish we could move along a little faster, but we have no timetable to adhere to, no jobs requiring our presence, and so no real reason to rush. Not for everyone of course, but if you’re involved in long distance voyaging, I guess speed is not the big issue.

Over the years I suspect our tolerance of what is an acceptable speed has become wildly different to most, given the number of Bermudian rig boats we see motoring with a fair breeze crying out to be used.

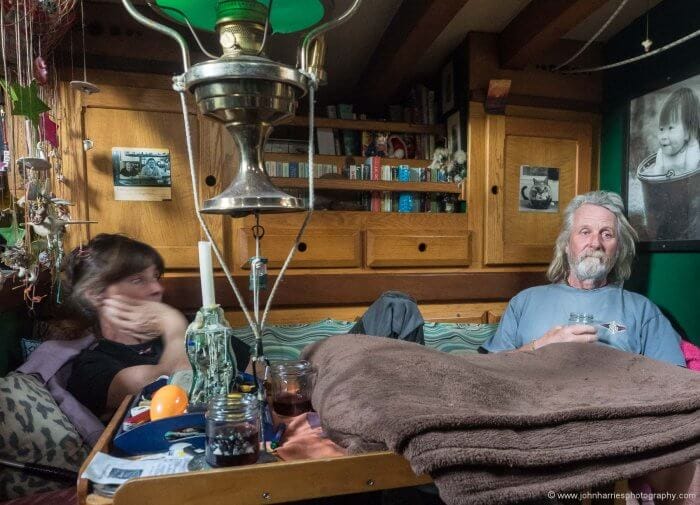

With a boat like ours comes the additional benefit that this beamy hull happily accepts a small library of books (around 700 at the last count), not to mention a cast iron wood-burning stove to read by.

No Need To Go To The Gym

Hannah certainly is a heavy boat with heavy gear, and you need to be reasonably fit to sail her. Both mizzen and main have throat and peak haly’ds and no mast winches. Both haly’ds are hauled by one person (Bee) at the same time. No furling gear.

The stays’l is hanked on but the jib set flying on the end of a 3-metre bowsprit, but we don’t have to shimmy to the end of it to change the sail: the tack is attached to a traveller (a leathered iron ring) and then hauled out. Hauling on the haly’d raises the sail and the luff is tensioned via a downhaul. All pretty simple. We drop the jib by bearing away and blanketing it with the main before easing the lines away.

Gaff rig is low load with small masts; but the mains can be very big—we looked at one gaffer that had a 27′ boom—OK around the Solent perhaps but not suitable for what we had in mind.

Sail changes can be numerous—Hannah carries 13 sails and, like paper charts, they take up a lot of room—but having to go onto the foredeck to change the jib means we keep a very sharp eye on what the barometer and clouds are doing, change headsails early, and snug the boat down at night to ensure a comfortable night, not a wild one—we just keep the boat in our comfort zone.

Cheap To Maintain

Solid wood masts, lanyards, and deadeyes, etc., make for a boat that is easy and cheap to maintain. Ironwork is mild steel, rusts, but in the 22 years it has been on the boat little if any has been replaced. Stainless may look nice but it is not, I believe, as strong as galvanised steel and is more expensive to boot.

- We recently replaced the inner forestay…US$38.

- A bail broke when we were in Spain many years ago. I removed it and took it to a garage to be welded…€4.

Interior

We have maintained the simple approach inside too. For years we used a Taylor cooker, but the escalating cost of spares pushed us to a cheaper, simpler solution: a gimballed “Primus”. Paraffin has always been easy for us to find, and we top up whenever the chance occurs. K1 kero is ok but the best has always been Jet Fuel A, which we can get from small airfields. We carry about 130 litres in jugs. Paraffin in Greenland is good too. We bake bread using a Dutch oven.

Our lights are LED but we frequently use an Aladdin oil lamp as it is bright enough to read by. Whilst on night watch we keep it turned down low, as it allows visibility below without ruining night vision, and adds warmth to the cabin too.

Equipment

We do have and use an engine and, whilst the cruising areas we like have either too much or, more often, too little wind, we rarely bother motoring on passage. If the wind fails we drift. If we’re several hundred miles or more offshore we really can’t be bothered to stand at the tiller for hours on end steering (we have no auto-pilot but do have a wind-vane). Monotonous doesn’t come into it, so we drop everything, sometimes leaving a staysail up, and let the currents take us where they will.

Many times we end up a few miles closer to the destination, sometimes we lose a few miles, but it gives us a great chance to catch up on sleep, saves on diesel and, on a journey of several weeks, another day or so doesn’t really make that much difference. The wind will return eventually.

We’re not Luddites and we’d be idiots going to sea without a GPS. They work, they’re accurate, and they offer a huge safety margin over sextants.

We use a mixture of paper charts and free electronic charts on a laptop with a $35 GPS dongle. We do not have paper charts for every area we cruise and they, like the electronic ones, are not up to date or anywhere near it. But the charts are better than folks had years ago and we’re relatively cautious in our approach and our sailing.

The radar, a Furuno 1613, we added after many years spent negotiating Maine/Nova Scotia/Newfoundland without one, but if we hadn’t spent so much time in foggy areas we probably would not have bothered.

The AIS receiver has been a boon, but we’re pretty useless at bothering with the weather, so the SSB receiver doesn’t get that much use. For ocean crossings I mean—there we tend to get a single station forecast and deal with whatever we get on passage.

Safety

We take an old-fashioned view about this sort of thing, mostly because, as a soldier at Kiel in the sixties, I taught other soldiers to sail, and safety obsession, EPIRBs and the rest of it, were all in the future. The boats were engineless (and most other things -less) but we did learn the importance of staying on board—one hand for the boat, etc.—acknowledging and accepting that sailing small boats has a risk element. It still does.

Whilst we do have life-jackets, we have never yet worn them, but have sometimes used a harness. It doesn’t make us better. Or worse. It is simply our choice of how we do it.

A Go-Anywhere Boat

We were recently on Morgan’s Cloud and marvelled at the complexity, the massive winches, the beautiful sail material, and how well thought-out the boat was, and came away with ideas we could adapt to make life simpler aboard Hannah (I know it sounds a contradiction).

MC is a go-anywhere boat—strong, practical—and we dreamt of how comfortable our life aboard would be compared to Hannah…however, all way beyond our price range.

But Hannah too is a go-anywhere boat and, whilst our approach to what we do differs dramatically from how John and Phyllis deal with life aboard, our voyages have shared many similarities.

The Bottom Line x 2

Finally…Despite having had our share of rough weather, Bee and I would still say that the single most difficult thing to deal with is not the storms, but saying goodbye to friends you have made knowing that, because of the lifestyle, you may never see them again—tough times.

Finally, finally…In the 15 years we have been doing this, we have spent somewhere between US$200,000 and US$240,000: that’s boat, sails, engines, living expenses, visas, booze, the lot.

It is a lot of money when looked at like that. Friends have done it on less. You’ll spend what you have. But don’t be persuaded that living and voyaging has to be horrendously expensive. Many, many unknown sailors are happily crossing oceans on a fraction of what is deemed necessary.

Think outside the box.

Further Reading

- You can learn more about Mick, Bee, Hannah, Toots, and their voyages over at their blog, but put some time aside, it’s addictive.

- Getting Out There Cruising Online Book (Members*)

*Non-members can read the Online Book Introductions and Tables of Contents, to assess their value before joining, at the above links.

Thank You

A huge thank you to Russ Nichols, SV Walkabout, for granting the rights to use his great photos of Hannah in Labrador.

Oh boy do I love gaffers an how gorgeous Hannah is. Great post and life lesson. Cheers!

Richard, thank you….if there is a lesson to be learnt here it might that we should always ensure our lazy jacks are slacked off enough as we’ll never know when that incriminating photograph will appear.

M

I didn’t even notice… But no worries, they are called “lazy” for a reason 🙂

Voyaging back in the day was certainly a far cry from today’s organized flotillas of million dollar electronic palaces with all the comforts of home. As someone old enough to have met David Lewis, Bill Nance, and John Guzzwell and listened to their sea stories, It is refreshing to hear of someone who still rejects the umbilical cord to land.

Least one believe that exemplary voyages cannot be made in cement boats, remember Bob and Nancy Griffith’s voyages on Awahnee in the 1970’s.

http://www.stexboat.com/books/circumnav/ci_21.htm

And in addition:

http://www.insidemystery.org/navigation/awahnee.html

http://www.amazon.com/Blue-Water-Self-Reliant-Sailboat-Cruising/dp/0914814192/ref=cm_cr_pr_product_top

Thanks Mick – refreshing first post.

When you heave-to in gale/storm conditions, is it best to centralise your sail around the main-mast (reduce yawing), or drop the main and run with jib and mizzen? What sail combination do you find works best? Since we have a mast-head sloop rig with a moderately long fin keel, my interest is purely ‘academic’, although I once raced against a ferro yacht in the UK that took delight in hailing “concrete”, with absolutely no correlation to which tack they were on!

Rob

Rob,

We use a combination of techniques depending on circumstances/how we feel. In big blows and seas I prefer to get the main down and heave to under stays’l alone or stays’l and try. Mostly this is because I want the boom and gaff down low and secured. Hannah is ok under stays’l alone lying about 60 degrees off the wind, creates a decent slick and is “comfortable’ below. If we’re stopping for a rest we can heave to under main and backed stays’l but it requires more fine tuning. The mizzen/heads’l combo is wonderful when it picks up from a stern quarter, restful without losing too much speed if the winds are 30+ but I don’t think we’ve used it to heave to.

I have heard of folks yelling “concrete” in close call situations although oddly enough we find the sight of the bowsprit bearing down on folks tends to concentrate a crews attention pretty sharpish..

M

Very nice article. And a nice reminder about slowing down and simplifying where possible, especially as I prepare for a Tahiti – Hawaii – Alaska voyage in the coming months. Thank you!

Hi Mick

great post, and a great reminder that real voyaging can be made on a small budget!

Best wishes

Colin

Thank you. Slowing down and the full time, constant proximity of your partner is definitely one of the key things to understand and come to terms with if you want this (or any other) life to continue.

Enjoy the forthcoming trip.

M

Hi Mick.

Thanks. Great stuff! Love it!

Many boaters seem to have completely lost their bearings when it comes to what a boat neds of equipment. On this site, most are quite focused on equipment that has an important function, but even here I think many of us might go too far when we fall in love with the coolest equipment. Yes, it’s doing the job better than a simpler version, or none, but only when it actually works and only at a cost that is always more than money.

I’m a multihull fanatic with a “need for speed”, I love very light boats in high-tech materials and i love to look for better solutions. This sounds like I’d disagree with your philosophy on the advantages of simplicity, but I don’t. Decades of racing have taught me that nothing beats simplicity.

You mention that just not having it, whatever it is, can make the difference between actually sailing or not. The cost or time spent making the boat “perfect” and “complete” can be extended unnecessarily, maybe into too late and abandonment.

Simplicity can be seen in many ways though. A ferrocement, gaff rigged, classic style boat like yours, can certainly qualify, but so can a high tech design, if designed, built and equipped the right way. As mentioned extreme racers are normally quite simple and stripped of anything not essential. I strongly believe in that type of attitude for long distance cruising. I think many long distance sailors would prefer it, if they tried it.

I like the style of your boat and life. I think it keeps alive much more of what is in the romantic image of the voyages of the past. I think the image and those ways of life actually makes that adventure become reality. As just described, I’d choose a different type of boat, and I’m aware that I’d lose that effect, but gain some in other ways.

What I’ll never be tired of hearing, or repeating, is the gospel of simplicity. In your article here I think you made it clear and showed how it can even be an attractive solution.

Thank you. I’m not against equipment as such but somehow the belief that the “right” equipment somehow makes you a “genuine” cruiser seems to have become a badge.

At the risk of boring everyone I was, in a previous life a keen bike – camper. I read avidly, researched equipment and had a pretty cool bike. I went to India and within 48 hours had wrecked my forks and front wheel. In Europe I would have replaced both items but that wasn’t a choice where I was so carried on. That wasn’t the lesson I learned though. During the seven months I spent there I met a guy who had cycled from the UK to India on a bike he paid coppers for. From a junk shop. To my equipment biased brain it looked fit for the scrap heap and yet he had cycled to India whilst I had flown and I realised then that it is really the spirit of the person(s) that make the difference not the equipment. OK in a competitive field equipment can make all the difference but that isn’t where we are in our lives. Well Bee still remains fiercely competitive..

“but so can a high tech design, if designed, built and equipped the right way. As mentioned extreme racers are normally quite simple and stripped of anything not essential. I strongly believe in that type of attitude for long distance cruising.”

That may be so but Hannah is our home and carries our dreams and well being. Given the choice between doubling our daily speed and having access to all our books and music, essential to us despite the weight, we’d stick with what we have. And no we’re not going down the Kindle road! But you’re right in that we have met folks who are using ex-racing boats and move from place to place at warp speed as far as we’re concerned. But without exception all were on short term lives aboard; a two year sabbatical rather than a life-style choice. Equally we have met boats that qualify as expedition craft that we look at enviously, imagining ourselves pushing further into the Arctic Circle than the “toe in the water” we’ve managed. Yet the owners have no intention of anything more than a few seasons in the Caribbean, flying home every 6 months. Obviously people have the right to make their own choice about what will work for them; all I was attempting to do was suggest that the magazine driven approach to cruising doesn’t have to be the only path and if your pockets are shallow, a rewarding and interesting life can still be available to you. To my surprise people seem to, so far, agree.

Lastly, I agree we’re probably coming to this from the same page, albeit in different books and I have appreciated your positive input.

M

We don’t yet have the confidence to take such a self sufficient approach, but your piece is inspirational.

It is also, if I may say so, beautifully, sparely written (until that final jarring cliché brought me rudely back from my reverie – ouch!).

Wishing you the winds you wish for yourselves.

Mark

Mark,

Thank you very much for the extremely kind words and compliments. I have no defense for the cliché other than laziness. As Gore Vidal once said of someone..”He’s not a writer, he’s a typist…”

M

mick, this is impressive…i guess you know that lynn and larry pardey don’t even have auxiliary power on their boat taleisin…remarkable…can you give a few more details re your fresh water system please ? i believe you indicate yours is not pressurized…so do you store it in jerry cans ? and i presume you catch rain whenever possible ? thanks…richard in tampa bay (but soon to head out for the antilles)

Richard,

Thank you.

Yes we do know of the Pardey’s although have never met them and certainly would NOT put ourselves at their level. We did think about being engineless but Hannah draws 7′ (2.10m) and weighs around 17T. More importantly I don’t feel I have the skill set to be able to sail everywhere.

Fresh water. The tank is an ex-industrial s/s sink (suitable adapted) that holds around 150litres and is pumped up via a foot pump. We also have about 200litres in jerry cans which we carry in one of the cockpit lockers. The tank is sufficient for about 2 weeks normal use and we can probably go 6 weeks without refilling but never do. We have had a rain catcher for the last 7 years or so but have never got around to using it….mostly, it has to be said, ‘cos when it’s raining I don’t want to go out and rig it!

M

Thank you, Mick & Bee, for sharing your story. I always find it somewhat refreshing to see that yes, there are indeed people making a successful life for themselves out on the ocean without spending a fortune.

Your story’s particularly touching for GenY / millennials, as so many of us simply do not have the financial and employment opportunities that were available to our parents’ generation. The idea of buying a $400,000 boat and spending $40,000 a year to run it is, for most people my age, utterly absurd. However, buying a $40,000 boat and spending $15,000 a year is vastly more realistic and potentially achievable.

I think a lot of people here would be very surprised by the number of 20- and 30-somethings who might be willing to give up most modern luxuries (as long as they can keep a laptop, a tablet and a good Wi-Fi booster) to live the voyaging life, if only they knew it was a realistic possibility.

(I have a few partially-formed ideas for such back-to-basics boats…. there are a few designers, George Buehler and Bruce Roberts come immediately to mind, who share this idea of sturdy, robust, cost-efficient boats drawing their heritage more from commercial fishing than from racing. It’s a sector that I would love to see a lot more interest in.)

Matt,

You raise some interesting points on the finances of living this sort of life and I would agree $400k as a starting point is a ludicrous amount of money and way out of the range of many people. Even $15k a year is still a lot of money to come up with so this is probably going to seem pedantic but the budget we lived on for much of the first 13 years drifted between $5000 and $7000 pa which covered food, fuel and general living expenses. Capital items: sails, engines etc we covered with a savings account or by working when in the UK. I mention this as I want people on limited incomes to know you can get by with very very little, provided you have some form of nest egg you can call upon if needed. Even now, flush with various pensions, we still bumble along on less than $10k.

For anyone who hasn’t yet come across it I’d suggest a look at Annie Hill’s “Voyaging on a Small Income”. It is probably dated by now but I think the core is still very valid. It gave us a tremendous boost when we first read it and realised that our, seemingly, unattainable dreams may actually be possible. An exciting time!

M

Hi Matt,

I had a lot of fun talking about design concepts for the A 40 in its development stages, but like you I don’t consider a cash outlay of 200+k affordable or “attainable” for a younger member of the now nearly extinct middle class unless they were lucky enough to ride the property bubble escalator in Vancouver or Toronto and escape before it pops. I know my friend who moved back to Calgary in 2012 to expand her yoga studio isn’t going cruising any time soon—-.

So here is a short list of 50 k boats that will get the job done. And perhaps do it better than a new 150k condo design.

Valiant 40 blister boats. 4 or five on the market at any given time with asking prices under 50k. In this group you’ll find some with new sails, dyform/staylock rigs, Lighthouse windlasses, Monitor wind vanes & the desired chainplate replacement. And even some without blisters! But blisters won’t sink the boat or make the keel fall off.

Bare aluminum Camper & Nicholson 36 that was originally Peter Nicholson’s personal boat . Nicely cruise equipped with hard dodger, watermaker and quality sails from Carol Hasse. 37k ask. But you’ll have to start your cruise in Tahiti—-.

Frers 44 built to the same design as a Hylass 44, only nicer. Buy it for 50k. It will need some out fitting, new standing rig etc. so it isn’t really a 50k sailaway, but 70k would have it ready to circumnavigate.

The tropic sunset will look better from either of these boats than from the deck of the 300′ Malteese Falcon that poor Tom Perkins couldn’t afford to keep up and sold to the Russian Mafia—.

Hi Richard,

To me, a key take away from Mick’s article, and what has made it work for them, is that they didn’t buy a refit boat. Instead, by shopping in an unloved part of the market (ferro cement and gaff rig) they got a boat that was in great shape and ready to go for a very small amount of money.

While I agree that the old boats you mention may be a road to cruising on less, I also need to point out, as I have in the past, that most will require a huge amount of work and at least the same amount as the purchase price in refit expenses—they are not $50,000 boats, in most cases they are $100,000 and at least three years of work boats. And further that the buyer will need the kind of deep skill library that you have to make it work.

And I’m not taking here about adding a lot of unnecessary stuff. This kind of time and money will be required just to make the boats safe and stop water from pouring in through every fitting, hatch and port every time they are sailed offshore

In summary, most of old boats are in need of a refit and will cost the buyer two to three times what “Hannah” cost Mick and Bee before they are ready to take on the kinds of voyages that “Hannah” handles so well.

Of course there are exceptions to the above, and the boats you list may be those exceptions, but it’s also important to understand that accurately determining which old boat is good one among the hundreds of value traps requires huge skill and experience that most of those new to voyaging don’t have.

Hi John,

I know we have different perspectives— and I understand the validity of yours. There are certainly pitfalls awaiting the naive, but those pitfalls are not limited to older boats.

To me a Valiant 40 blister boat fits exactly into the unloved segment of the market you mention. There is no question about the excellence of the design and its sailing characteristics— unlike the choice of a cement boat or a one-off that is cheap because nobody knows anything about it.

Out of 170 odd examples from the blister years, only a handful have blister conditions that are actually structural. And even those won’t sink because of the blisters.

In my sample:

Updated hatches are common, remedying the primary leak point in the early versions.

Many have new standing rigging and recent sail inventories

Most have autopilots and wind vanes

Several have new or newer engines

Two have Lighthouse windlasses

One has new chainplates. A very straightforward job that should be done on all of them.

Any of them can be bought for 45k. In fact I’ll be soon inspecting one with an eye to my own purchase. Like any design there are things I don’t like, and if I had 200k or 400k I wouldn’t be buying one even if it were new, but I’d rather be sailing than dreaming.

I’ve sold several of these boats and personally inspected Mark Schrader’s V40 just after he returned from his first solo non-stop circumnavigation. And I know for a fact that it won’t take anywhere near an additional 50k and three years to make one of them equal to his factory demo model that he sailed around Cape Horn.

Look through most of the new 200k boats on the market, and you’ll find disasters waiting to happen that won’t be there on your blister V40 if you’ve exercised a measure of common sense in setting priorities. Take a glance at the thru-hull fittings that came out of Richard Spindler’s (Latitude 38) 450k Leopard 45 production catamaran and tell me how many design errors and potential disasters they represent!

I rest my case!

Thank you Mick for sharing your life and spirit and beautiful boat, and helping us all to refocus our dreams and prioritising our cruising path.

Cheers

Michael

I have many friends who cruise, as a lifestyle, and have met many more. The idea has long appealed to me. Now, after sailing around the Caribbean and New England waters for many years and not so much recently, I often fantasize about doing it again. But, I have a new consideration: and almost 9 year old son. The problem is I am single parent, I am 65 years of age and his mother is still in contact with him and, I am not sure she would approve of me taking off with him. Well, maybe for the summer. Anyway, reading your article caused me to have some positive thoughts about giving it a whirl…

Hi everyone,

I thought I might mention some of the advantages I have noticed over the years to traveling with limited resources. If your goal (or at least part of it) is to get to know the various countries that your travels take you to, then there are (at least) two conditions that will pave the way into a more intimate contact with local people and communities: cruising with children and having limited resources (and clearly these conditions often go together).

Children open doors everywhere, but, in my observation, so does limited resources. Cruisers who enter a community who have resources end up in a commercial marina and gravitate to the commercial operations for the boating community. They meet and deal with people in the service professions, who certainly can be and often are, wonderful, but their livelihood is in service and that is how they will (initially) respond to you: as a customer.

Someone who is (truly*) on a tight budget will poke around and find local alternatives to the commercial marina (or the marine fabrication shop/chandlery etc.). They will engage the people they meet on a more intimate personal way and, almost invariably, will find alternatives: a raft to a local fishing boat or an empty private pontoon or a welder who cares for automobiles rather than yachts. That evening they will have their “hosts” for drinks or coffee. Language barriers will diminish as a tour of the boat commences and pointing/pantomime takes place. Pretty quickly the cruisers feel part of the community in a way that can be more challenging for those whose interactions are largely with service people.

Cruising with children just makes becoming a part of the community that much easier and quicker.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

*Please be clear that I am referring to people who are truly cruising with limited resources: little is more off-putting than a cruiser whose intention is to “get over” on a cruising destination and its people, service or otherwise.

Hi RDE,

If you end up joining the Valiant family, please come to the discussions on the Valiant web site as I am sure you will have valuable contributions pertinent to Valiants in the same way you do here on AAC.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

A beautiful read. The paradox of modern cruising isn’t necessarily the gadgets and comforts, I find, it’s having the skill set to do without them. Learning marlinspike seamanship, such as splicing and sail repair, learning how to “make and mend” and learning how to sail conservatively, off the calendar, save for an awareness of the seasons, are all difficult for people not born to this lifestyle. The time limitations can lead to an overcompensation in the boat acquisition, as people hope that burning currency will appease Neptune.

The other take-away for me is strength and a tolerance for a certain level of discomfort or absence of modern conveniences. Working a boat with muscle power makes you (or keeps you) quite fit in back and limbs, but if you aren’t fit to start with, or if you’ve bought too much boat, you could injure or endanger yourself. Same with modern conveniences: hot water in a black bag over a cockpit is not how many (even with weather cloths) would care to clean themselves, but hot pressure water in an enclosed shower stall brings its own issues. It’s nice to see the simple side, but it’s made me aware, as someone who didn’t sail under age 38, that there’s only so simple I can get. Partly that’s just because we are bringing a teenager who will be schooled aboard, meaning we must provide some means of communication…and a quick way to get clean…and partly it’s because I understand and appreciate items like radar, AIS and a simple PC-based plotter in aiding and abetting, but not replacing, keeping a proper watch. Other than that, there is much to admire and to emulate in the choices you’ve made and the life you are living. Fair winds.

Hi Marc,

Lot’s of good points, thank you. I have a post in much the same vein coming.

Marc,

Thank you for the kind words.

The key point in your comment, for me, is ” there’s only so simple I can get.” My intention was never to suggest that we had the correct way of doing it only that there is a simpler way which you clearly understood and appreciated. For you and your family it may be a step too far but for others, perhaps at a different point in the quest for a life afloat it may give them some thought.

Good luck with your future plans

M

Thanks for the reply. The complexity in our case is both choice and opportunity. As we are bringing a highschooler whose mother has a teaching degree, we need a certain level of communications ability. We have a steel boat with a full keel, as well, and we are capable of carrying a fair amount of batteries where they will do the most good as internal ballast. This leads to solar panels, etc. but our actual gadget tally is less than most cruisers, but is geared toward “independence from the shore” and self-repair. Having said that, were it just my wife and I, things would be more simple, and I’d probably have a solid fuel stove and just oars for the tender. I think the key element is to find a partner for sailing who has similar goals and aspirations, and, dare I say it, tolerances. This is clear from reading the Smeaton and Hiscock stories from the ’50s and ’60s, where damp wool and a mug of OXO was near the limit of the comforts, and marinas and rescue teams didn’t exist. Yes, we’ll have GPS, AIS and RADAR, but I can swing a lead line and use a sextant, and will take pride in the more manual, muscle-powered aspect of sailing, just out of pride and the need to keep fit and alert.

To me, Hannah’s beautiful under full sail.

A lovely read Mick, thanks. Enjoying the blog as well. Fair winds ~

Wonderful article, Mick, thanks, have referred it to a number of friends & reposted on Facebook.

I have the same problem with my Taylor type paraffin stoves. What is the make of your Primus? I can look this up online.

Cheers.

Nick,

Hah that explains the fb hits we’ve been getting.!

We first changed to a Butterfly brand, available in the US from St Pauls Mercantile. We simply used the Taylor’s as the gimbal. Wasn’t perfect as the balance was wrong but it got us through a year or so. The one we use now is a Rhino. We got ours second hand but they were available from Atomvoyagers.com but he seems to have stopped trading. He has the plans of the gimbal arrangement on his site so it is possible to build (if you’re a stainless welder) or have built. However the Rhino and the Butterfly are not interchangeable so the plan would need to be altered a little. The beauty is partly in the cost, about $55 for a complete stove. I think you’re in Ireland from memory so you could probably find something in http://www.base-camp.co.uk

M

Thanks, Mick.

Hi Mick, Thankyou for your inspiration. The reading of your blog was a major factor in encouraging us to buy a cruising boat & take off. Your marvellously retold adventures are much appreciated. Cheers. ruthndave. Black Dog