In Part 1 Kurt explained the fundamental forces acting on preventers and why we must get the angles right.

In this chapter he shares:

- A simple method to calculate the loads on our own boats, including a spreadsheet.

- A table of examples using well-known boat designs that we can sanity check our results against.

- Detailed preventer construction recommendations.

Simplified Model

My computer model addresses the various complexities, including dynamic loads due to momentum and boom swing due to preventer stretch, which allowed me to make a more complete evaluation of the loads over the full range of motion to determine both the peak and final preventer tension.

While this detailed analysis is insightful, it is probably unnecessary for basic preventer design on a typical boat.

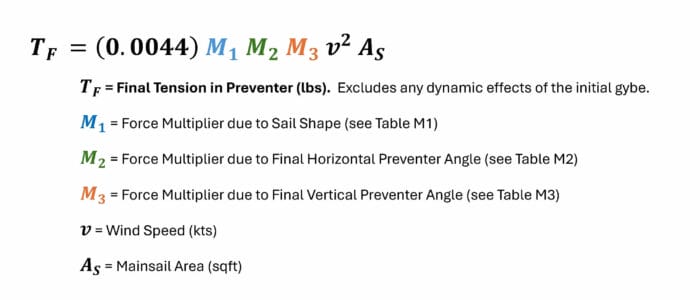

The following simplified methodology, using the equation at the top of the chapter, provides skippers with a tool to evaluate a particular boat’s final preventer tension so that all the components can be sized accordingly.

To make this even easier, we have provided a spreadsheet that does all the required calculations based on a few simple inputs.

Brilliant. This is why we subscribe and very happily pay!

Excellent. Thanks.

Many thanks for making this simple to understand

Thank you for the excellent information.

Kurt, thanks for the excellent data and spreadsheet. It’s clear that the turning block at the bow carries the highest potential loads. I have just upgraded to a new 70mm plain bearing Selden block, attached to our integral aluminum toerail’s 25mm top bar with a dyneema soft shackle.

The boom sweep angles in your table seem relatively small at 3-4˚, so the distance the boom has for acceleration is limited.

Something that has always concerned me is lthe oad placed on the mainsheet hardware and boom during a “normal” planned gybe in strong wind. Normally we sheet the main quite far towards the center before gybing, but there always seems to be more movement in the boom than I would like, 10-30˚ or more. And no matter how gently Helen eases us across the wind I always cringe when the boom finally crosses over. Bang!

I’d be interested in hearing how others perform a controlled gybe in 3-4m following seas and 25-30 knots of true wind. Main would not normally be reefed due to apparent wind decrease. Our main is 450 sq. feet, fully battened, 43′ cutter. I remember Beth and Evans on their Samoa 47(which has a huge main) replaced their traveler line with a dynamic (stretchier) 11mm climbing rope to provide some shock absorption. I wonder about the mechanics of this.

Keep up the good work!

Brian on Helacious…in Sweden

Hi Brian,

We will be getting more into usage in my part three, but I can answer this one now: if the jibe is too violent I would suggest that the first thing to think about is reefing earlier. On the M&R 56 down wind or broad reaching we would have one reef in about 22 true and two in at about 25 and three once over 30. To be blunt I think you are driving the boat way too hard for safe short handed sailing by having a full main up in 30 knots.

It’s important to remember that wind pressure scales by the square of wind speed and there is very little, if any, speed loss from reefing a bit earlier. Reefing earlier also means that if something goes wrong the loads are less likely to cause damage, and finally, it will be way easier to get back on course and things under control in the event of being caught aback. Oh yes, and it’s easier on the autopilot.

As to using DCR, I don’t think I would do that since it will make properly preloading the preventer more difficult to judge.

Good advice, John, thanks. In general we reef when conditions require it. Downwind in 25 knots (of warm air, not Greenland dense air) we’d be making 7 kts,or so, which puts the apparent wind at 18 or 19. By 30, yes, I’m sure we would reef. I much prefer keeping speed up when saiing downwind. I think it actually puts less load on the autopilot since we are overtaken by fewer waves and get slewed about less frequently, but it also depends on how steady the wind direction is. Of course there’s a point when the waves get too large and surfing begins, but fortunately we’ve mostly avoided that. 5m is about our maximum experience.

I would benefit from a detailed discussion of safe open-ocean gybe (or jibe) technique. I didn’t find the subject covered on the site.

Hi Brian,

There is really nothing to say about a “safe open ocean jibe”. Safe jibing is always the same: trim the main in before the jibe, and let it out as soon as it comes across. There is nothing I can add that will change the forces at work. Therefore I stick with my original recommendation: if the jibe feels too violent we have too much sail up, it’s that simple.

One other thought: I assume you are using wind instruments to measure true wind but unless you have fully calibrated them, and maintain that calibration regularly, the way a full on race boat does, they are almost certainly reading low when you are sailing off the wind, so it may be blowing way harder than you think. And once again, remember wind pressure scales by the square of wind speed, so if you are, for example, reading just 5 knots low off the wind (very likely) the wind pressure would be way higher.

And yes, I agree that keeping speed up is important, but I still think you need to look at this from the angle of being consistently over canvased. Judging safe sail area off the wind, particularly in waves, is one of the hardest things to do in offshore sailing.

John, Can you explain why wind instruments are prone to reading low in down wind sailing? Sailing downwind offshore Nomad (Sabre 38 Mk I) is both steadier and faster with a well-reefed main, fine tuning power by rolling the headsail in or out. I am always surprised at how much power I get with the main double reefed in what seems like 20 knots true.

Hi Seth,

Hum, not sure I even know, but factors such as heal, upwash from the sails, and motion of the rig all affect accuracy, and then of course boat speed through the water must be right on and that’s affected by heal angle, motion, and different boundary layer thickness at different speeds. And then of course there is nothing to calibrate apparent wind speed against, unless we have an accurate wind tunnel test facility.

And then these errors seem to scale larger in the process of calculating true wind, and I have noticed that generally when I bear off indicated true wind drops too.

Of course that could all conspire to make the true wind read high too, so there is nothing definitive here, that says true wind will be lower when running, at least that I know of, although perhaps upwash from the sails changes.

What I do know from playing with our top end H5000 system on the J/109 (came with the boat) that it’s fantastically difficult to get true wind speed and angle accurate on all points of sail, even though the system has calibration tables for each wind true wind angle and wind speed band as well as for boat speed bands, which most gear on cruising boats does not have. (Pro race boats spend literally days calibrating a system like the H5000 to get true wind speed and angle accurate.)

Anyway, I have found is that over reliance on true wind speed numbers is a mistake and that it’s best to do as you do and reef the main conservatively while balancing the loads with the headsail.

Hi Brian,

One other thought for you: you may be leaving too much main up in relation to the jib. I see this all the time because the jib is easy to reef down so off the wind and reaching people tend to roll it before reefing the main, and therefore leave too much load on the main. The main should always be reefed first at each step of reducing sail. Then, when jibing, particularly in the ocean, you can roll up the jib most of the way to make it easy, and then jibe with a much smaller main, before unrolling the headsail again. Keeps things nice and controlled.

I watched a video from Tom Tursi at Maryland School of Sailing, where we did our basic training. Although I don’t approve of his exact preventer setup, I determined I am having difficulty bringing the main boom to the center because I’m not putting the traveler all the way to windward first, then sheeting the main hard to the traveler, then centering the traveler (and boom) before executing the gybe. It will be much easier to bring the boom in those last 10-15˚ via the traveler. And certainly would be easier with a smaller sail!

We have a Maretron ultrasonic wind sensor high above the mast head, connected to our N2K network and displayed both on a B&G Zeus 3 and a Maretron DSM250. It seems consistent in calculating the apparent wind as we change course and proceed from wind ahead of beam to aft of beam. Sorry to sort of hijack the preventer thread. While my preventer setup is pretty bombproof, and we use it religiously when the wind is aft of the beam, I realized I was not happy with my ” controlled” gybe. Thank you for indulging my curiosity, I now have some actionable information.

Best Regrads, Brian on Helacious

I have to second John’s comment. When heading downwind, I’ve found most boats are much more directionally stable when being “pulled” by the foresails rather than pushed by the main. The main is off to the side causing rotational forces around the keel & boats axis of rotation. Reefing the main down first reduces this tendency and is much easier on the autopilot.

Hi Brian,

I have played around with different traveler lines on our CS36T with mid boom sheeting. By far the biggest benefit of a lower modulus line to us is in slatty conditions where the slamming is not nearly as bad as when we had much stiffer line in there. With stiff line, it would sound like the rig was going to come down every time a powerboat waked us badly but now it isn’t bad. The stretch does help a little with jibing but only a little and we do not jibe any differently than before.

If it gets too stretchy, it is bad too. For one, your sail control will suffer when going upwind and it will be hard to get the traveler right. It will also hurt you in preloading your preventer.

On our boat, we ended up with 3/8″ double braid nylon with a 4 part purchase on each side which is actually reasonably beefy for a boat our size. When hard on the wind right before reefing, the leeward traveler line will just start going slack slightly where I can see it is not longer straight but it is still not touching the track. It has not been a problem with the preventer but a previous version with very stretchy line was and we had to drop the traveler to improve the geometry although this is a bit self-defeating as you have more line involved so we sometimes dropped it all the way onto the stop. I do like the system we have now but wouldn’t want to go much stretchier and if we raced, we would probably want regular polyester.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Thanks for the fill on that, particularly since after thinking about it I was wondering if I was wrong to discourage Brian from using DCR. My concern was that this would make it more difficult to get a reliable preload on the preventer without putting too much load on the mainsheet. So good to know that was right to worry. By coincidence, while I was thinking about this last night it struck me that we could solve that problem by always dropping the traveler to the stop when the preventer was rigged. But, on the other hand, I’m always nervous of solutions that require us to do that kind of thing every time to be safe, and also a lot of stops I have seen are sketchy.

Thanks for posting these articles. My two main takes: tension the preventer to eliminate movement and peak loads, run the preventer across the bow to the windward side to reduce loading on the blocks. This latter point was a light bulb moment for me. In my line of work I inspect lifting arrangements and often I see padeyes above a fixed winch that are equal to the WLL of the winch, when it should be twice that (sure you can get away with 1.5 or even 1.25 as the safety factors will allow that). However, for the gybe preventer, where a sharp turn is created at the bow, this is such an obvious solution. Also, at least on my boat, having a gybe preventer control on the windward side is just less clutter as I will have genoa and staysail sheets on the leeward side. A minor point, but clutter is never a good idea and if it can be avoided, it should. Of course goose winged somewhat negates that.

Hi Alastair,

Very good points as usual. And I too have often been amazed by situations where the load increase from turning a line has been ignored. Kurt’s articles will go a long way to educating people about that, which will make them safer, and not just around preventers.

Yes. Your point is well made about getting the preventer on the windward side where you are more likely to have a free winch and less clutter. Thanks for this observation.

In your experience with lifting, what are the typical safety factors that are applied to the lifting hardware (shackles, etc.) where you have good testing documentation of a given components working load and breaking load specs? I believe the rope suppliers recommend 5:1 safety factor on rope for normal applications and 10:1 safety factor on rope in lifting applications. I believe these higher safety factors on rope are due to the many unknowns that affect rope’s strength (i.e., wear, knots, splices, bend radius, etc.). I’m curious what you see or recommend for safety factors on hardware that is less impacted by these sorts of unknowns.

Thank you Kurt.

Ive got some measuring to do.

And some maths to convert it all back to metric, i also didn’t see the tables for the force multiplication factors (in built into the spreadsheet i presume).

Just looking at the sanity check figures i can see my preventer was underspecified. We would most likely be reefed by the time we were possibly getting 35kt squalls but its a good reference as “most likely” is a long way from I will always be.

And up to this point I’ve used double braid polyester so more stretch, more movement and more force.

Hi Dan,

Yes, there are three hidden tabs on the spreadsheet that actually do the calculation.

Several years ago, your article on preventers encouraged me to join your site.

This practical work by Kurt, which puts the numbers out there, is instrumental in helping us understand the loads we are putting on our rig.

While I use the preventer as initially designed here on AAC, I have wondered if my turning block is up to the task. Kurt’s formula estimated 2053 lbs measurements on the turning block. I reached into my kit bag and grabbed what appeared to be a beefy block to use. I now need to examine the block’s working load.

Many new sailors fail to consider the issues involved

Thanks for this article.

The bow turning block can be a challenge. This element of the preventer system deserves the highest degree of scrutiny. The load ratings on most of your typical bearing blocks are generally too low for the calculated preventer loads on medium to large yachts. I think in these circumstances, you may need to look at frictionless eyes, with substantial dyneema loops or strops to attach the eye to the deck. I’ve seen some preventers set-up with this system and in general I think it is a good approach, but some of the examples I have seen appear to have strops that are undersized. The actual deck attachment also needs to be closely evaluated. Unfortunately, every boat is different so I can’t give specific recommendations, but hopefully the calculator helps define the forces to guide the evaluation and design needs.

It looks like the crossover arrangement might have three substantial advantages for fair-weather coastal sailors. First, it permits the use of a smaller (cheaper) diameter line. Second, it can run the line to a windward available winch. A big deal for those of us who would rather not buy one or two new winches. Third, it might permit using a single line for the preventer. The downside is leaving the boom swinging free for probably 2-3 minutes while adjusting the line—pulling in the old winch end to attach to the boom, then running the old boom end through a block at the toe rail and back to the new windward winch. This would be a risk if planning to jibe but not if conditions permit a chicken jibe and you head up before making the adjustment. I suppose the second half of the procedure also puts you on the leeward side to run it through the block and back to the winch.

What are your thoughts about the mechanics and risks of this arrangement?

I believe that you might be able to make a single-line work for both sides, but I think it is potentially boat dependent. Specifically, I think it will depend on the lifelines. If your preventer has to go under the lifelines to get to the boom, then a single preventer becomes more problematic. In my mind, the single line may be more problematic than simply running two separate lines, had have both cross-over at the bow. It is more line and more hardware, but ultimately may be more flexible from an operational standpoint.

Hi Scott,

I will be looking at the practicalities in Part 3, but I can say after 30 years of using preventers offshore I would always want two, one for each side. More coming.

Hi Scott,

Good points, but one caution, the cross over arrangement does not reduce the load on the line allowing the use of smaller line. It only reduces the load on the turning block at the bow.

Hi Kurt,

This is great. And I think the design point you have chosen makes a lot of sense. It would be very easy to pick an improbably high design point and then stack safety factors on top or similarly to pretend that we will never get caught in a squall but you have picked what to me is appropriately conservative.

One small thought on the cross-bow implementation is that this may put the preventer winch in a place where it is more likely to be underwater in case of an accidental jibe and being pinned. People on here with lots of experience racing IOR boats may have more thoughts on this, I have had that side of the cockpit be hard to access but never with a really critical to release line there so can’t say if this is a real issue, especially with a conservatively sailed cruising boat.

Eric

Hi Erik,

As someone who raced old IOR boats, you are right to be worried about the winch being underwater! That said, I think that at the end of the day we do have to assume, and encourage, that our audience of primarily short handed cruisers will be sensible and conservative about how they sail their boats. And if the boat is an old IOR design, that goes double.

Thanks, Eric. I’ve spent a fair amount of time debating the design criteria with myself so I’m glad you agree that it is appropriate. Ideally, we shouldn’t experience these conditions, but it does seem to be a potential scenario worth designing for.

I agree with your observation about the cross-over preventer being on the low-side in a post-gybe situation. This is certainly worth considering when choosing that option. I’m wondering how much the boat would heel post-gybe if the boom swing is limited to a few degrees by a stiff preventer. I’ve certainly experienced what you describe, but is usually after the boom has swung over close to the mid-line and the forces are acting perpendicular to the beam. In John Kretschmer’s video that John Harries re-posted here, there is only minimal heal after the gybe so I’m wondering if that is partly due to the limited boom swing. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on this.

Hi Kurt,

I can speak to that one. Generally having the boom retained by a preventer makes getting pinned with the old weather rail in the water more likely, not less.

Not sure of all the forces of work here, but I’m guessing that it is a function of the momentum in the fast uncontrolled veer toward the boom after the boat gets caught aback—much like a broach, only the other way around.

Anyway, having raced old IOR boats I have seen it enough to be pretty comfortable with that opinion. Stan Honey has said the same thing about preventers and he has pushed way more boats hard than I have. In fact really hard driven race boats don’t generally rig a preventer for just this reason—Stan and Sally never did on their Cal 40 when racing full out.

All that said, the primary reason that boats get pinned is too much sail up, so that’s the key seamanship take away here. As you point out, in John K’s video the boat hardly heals when caught aback, but that’s a function of conservative seamanship: It’s only blowing barely 20 (look at the sea state) but John has at least one reef in.

Fascinating article. When I enter my numbers in the spread sheet on a Mac running Ventura 13.6.9 and Nunbers, all the results other than sail area and preventer length show a red triangle and the note “Geometry::Table1::G127 contains an error”. Will this spread sheet run in a Mac or do I need a winidows machine and /or windows excel?

Hi Ian,

It runs fine on Excel for Mac, since that’s what I have. Compatibility with Numbers may be more of a problem, particularly with a spreadsheet this complex. I have found in the past that Excel compatibility in Pages is a bit sketchy. Maybe just borrow someone else’s computer with Excel loaded?

Sorry it isn’t working for you. If you want to give me your inputs I can check them on my end to make sure there isn’t a bug relating to your specific inputs.

Hello Kurt and John,

Thanks so much for providing this amazing tool. I’ve carefully measured my boat but can’t seem to get the spreadsheet to accept my inputs for “A” and “B” as they require a value between 0 and 0.6.

I’m also using a Mac and Google Sheets and don’t have access to Excel unfortunately.

I’ve attached a screenshot with the errors I get and I’ve typed in the two missing inputs for A (16.07ft) and B (1.97ft) just to the right of where they belong.

We currently use a Dyneema strop attached to the end of the boom and hitched via bowline to climbing rope and run forward to a low friction ring at the base of our cutter stay then back to a dedicated winch on the aft deck which is otherwise used for a running backstay. It leaves a lot to be desired and we did have an accidental gybe this summer that proved it. However, my husband is reluctant to go away from climbing rope in the fear that a rigid set up will be catastrophic if we were ever unlucky enough to stuff the end of the boom into a wave. I think locking the boom down will prove to be the lesser of two evils! Our boat is a 1990 Najad Aphrodite 510.

Many thanks,

Marina

Hi Marina,

Sorry, but the spreadsheet does not work on Google sheets, and we are not really in a position to fix that or to support more than one version. Maybe you have a friend with Excel you could ask to run it for you if you just send them the few inputs?

As to stretch, while I totally get your concern about boom dip, I would strongly recommend getting rid of the DCR, which stretches even more than marine nylon braid for the reasons Kurt explains in Part 1. Bottom line, with that much DCR in the system I’m guessing the preventer is not a lot better than not having one at all.

The absolute most stretchy line I would consider for this application is double braid Dacron

On boom dip, your comment has inspired me to write something on managing that risk. I will put it on the list.

Hi,

Also, keep in mind that DCR probably comes in at most 10.5mm diameter, which is very undersized for a 50+ ft boat in this application. But I’d make a wild guess that the rope has so much stretch that it’ll never get to the point of breaking.

My current preventer system utilizes a line led from the cockpit (under the dodger and through a clutch) forward to the base of the mast. It terminates with a snap shackle. From there it can be led forward through two heavy duty Harken snatch blocks on hard deck eyes and aft to where that snap shackle attaches to one of two lines (p/s) that have eye splices forward for the shackle. These two lines terminate aft on the boom to a large Dyneema strop. The nice thing about this system is the lines on the boom are always there and held up by shock cord. However, I wonder if attachments via the shackle is advisable and if securing the line in the cockpit with only the clutch is adequate? Thanks.

Hi Jesse,

I will be addressing these issues in part 3.

It is important to check the load ratings of all the various components. The load ratings on snatch blocks and snap shackles can be surprisingly low so I would recommend checking those. Pad eyes at the bow are more difficult to check from a load rating standpoint (not always published or marked), but these are also a concern because they see nearly double the preventer load due to the 180 degree turn. There have been documented failures of pad eyes so give these careful consideration (size of eye, deck attachment method, backing plate, etc.). Any rope components (strops, soft shackles, etc.) should carry at least a 5:1 safety factor to cover the uncertainties of material degradation, bending radius, splicing, etc.

Thanks for the article. Very keen to see Part 3 as I am about to apply the science from the first 2 articles to our Adams 45. Given the recommendations for high-modulus lines and cautions about the loads at the bow fittings, where ideally should the ‘fuse’ go in the system?

Hi John,

I’m working on it. On fusing, the general thinking from the engineers is we should not think that way in this case, but rather bring the entire system up to the same standard and safety margin—see comments to part 1.

That said, as you point out, I sure as hell would not want the bow fitting and turning block to be the weakest part because if it lets go someone could be in the bight of the line.

The turning block calculation on the spread sheet is confusing for me. I would like to know if the estimated total force at preventer turning block is for a 1 block or a 2 block setup which I would likely implement. I own a beneteau 57 and using the spreadsheet with approximate numbers I get 5200 lbs of total force at turning block. A block for 5200 lbs would be a Harken 75mm black magic and costs about $525. Before I buy 2 of these I would like to know what that number (total force at turning block) means. thanks in advance for your help.

Hi George,

The force calculated by the spreadsheet is for one block turning the line almost 180 degrees which effectively means the block and its attachments are subjected to twice the load on the line. Using two blocks reduces the load on each by about 45% so only a little more than the line load on each—see diagram in the article above.

John,

Thank you for the clarification. Therefore each block would need to be 5200 x(1-.45) = 2860?

Hi George,

That’s it. Also I am exploring this whole issue further in part 3, which is close to done and we will be publishing in the next couple of weeks.

Thank you for this! I’ll be revisiting my guesstimated preventer construction over the winter, and perhaps relaxing a bit more downwind.

Thanks a lot, this answer some of my worries. Except …

For those who want to use metric values, you can use Preventer-Calculator-Metric.xlsx.

If you save original Excel in the same folder as the metric version then the results from original should be shown in the metric one.

If you enter formula ='[Preventer-Calculator-Metric.xlsx]Sheet1′!D5 into cell C11 of original and copy to cells below, there will be no need to copy the values.

Now, why is this not part of the original version?

thanks so much, Gordan!

Hi John, 2 things,

2.also, some times I have used a brake when sailing up wind, and the main is lifting and dropping ( I have a soft vang) bc of weird wave pattern,, I suppose you would say not a good idea?

Hi Jim,

Yes, with only two winches there is no other option. That said, if it were me, I would consider adding a couple of secondary winches: https://www.morganscloud.com/2021/02/23/offshore-sailboat-winches-selection-and-positioning/

And as far as the boom lifting is concerned I would fix that right with a proper solid vang: https://www.morganscloud.com/2020/11/16/rigid-vangs/

Kurt/John–using the load calculation spreadsheet and all outputs show error (#NAME?). Excel for PC, v2410. Even just adjusting one parameter slightly makes everything go wonky. Macro issue? Another setting/authorization? By the way…AWESOME content and dedicated to setting up a proper preventer this next season so want to get it all right. Thanks!

Hi Bruce,

Hum, it’s working fine on my Mac Studio, latest version of Excel. I have emailed Kurt to see if he has any thoughts. v2410 just came out, so maybe Microsoft broke it. Would not be the first time!

Hi Bruce, Sorry it isn’t working for you. Not sure what may be causing the problem. I’ve checked a fresh copy from the website and don’t see any issues on this end. There are not any macros and the formulas are all pretty straightforward. The only feature that I think might cause a problem is some error checking we have incorporated to limit the inputs to within a certain reasonable range. If you were on an older version of Excel then those Error Checking features may not be supported. That’s my only thought.

If you want to send me your input values, I can test it on my end and send you the results.

Guys thanks for the quick response. I did find some funky responses to data validation & limits but what ultimately worked was opening it in Google Sheets as I had to anyways to share results with crew and all formulas worked. Go Figure. All set (for now), thanks!

In the table, “Example Rope Material and Size Recommendations”, in the “Preventer” column, does “B.L.” stand for Breaking Load?

Hi Lisa,

Yes, break load.

Do you see any reason to install a preventer on catamaran ?

Hi Philippe,

Absolutely, why would we not? An accidental jibe is potentialg dangerous regardless of number of hulls. The good news for multihulls is that if the preventer is run from the lee bow the geometry is better, so the loads are lower.

How can I be sure that I have 250lbs of pre-tension on the preventer? Do I put it around the winch and hand tighten? Should I use a winch handle?

Note, I am using an end boom attachment point for my preventer and I have mid-boom sheeting. So, I want to be careful not to bend the boom.

Hi David,

It’s not critical that that you preload to 250 lbs, Kurt is just sharing the assumptions he used in his calculator. Further down the chapter in recommendations he writes:

“Pre-tension preventer at least a modest amount to limit boom movement and mitigate shock loads.”

That said, given that you have mid boom sheeting, if it were me (or Eric Klem) I would move the preventer end point to the same location as the mainsheet to avoid boom bending. See Part 3 for a discussion of this trade off.

Thank you