One of the reasons many of the yachts arriving from the USA tend to bypass Yarmouth is their wish to give the local Cape Horn a wide berth. And with good reason, as Cape Sable is beset by ferocious tides and uneven shoals that can undoubtedly generate some pretty wicked overfalls with wind against tide. Throw in regular doses of dense fog due to a major cold water upwelling close to the Cape, and you’ll need no convincing to avoid this place in bad weather.

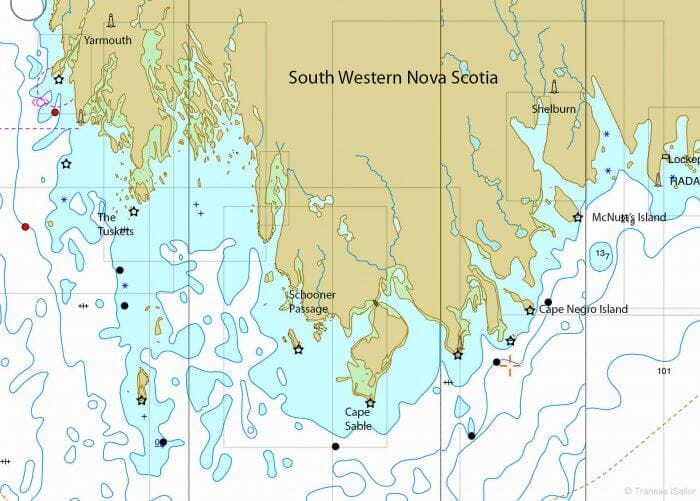

Being so close to the Bay of Fundy, the tidal range at Yarmouth is more than six feet greater than on the other side of Cape Sable, a mere 40 nm to the southeast, which means that the tidal streams between the two places can run at 3 knots or more, especially in and around Schooner Passage, through the Tusket Islands, and down towards the Cape.

There’s an additional complication, just to make life a little more entertaining, in that the flood tide starts two hours earlier at Cape Sable than at Yarmouth, so you have only four hours to fly down to round the Cape at slack water before the tide turns against you. Get it wrong with the prevailing southwesterly winds, and you could spend at least six thought-provoking hours being battered in the races off Cape Sable.

Knowing this, and having grown up facing as bad (and often worse) around the various Cape Horns of the British Isles and northern France, I tend to do my homework for any such passage very thoroughly indeed, having suffered the vividly memorable consequences of slack planning on more than a few occasions. Get it right and all will be well, though—it’s not that hard.

So it was with everything in our favour that we set off from Yarmouth dead on time, according to Peter Loveridge’s excellent pilot guide, at two hours before local High Water, followed by two Norwegian yachts who had evidently been swotting up the passage with equal diligence. Timing it like this means facing a diminishing foul tide for the first two hours before picking up a full four hours of fair tide down to the Cape, but it’s a tight-run thing so there’s no excuse to dawdle.

By the time we reached the Tuskets the tide was on the turn and we only had a short time to view the islands as we surged through. Once fairly populous, most of the inhabitants have now opted for the comforts of living on the mainland rather than the rugged remoteness of the islands, although there are apparently still a few hardy souls who stick it out all year round. But these are lonely enough places and it is hard to imagine they would hold much appeal for today’s digitally-obsessed young people, especially in winter, so it is hardly a surprise that families leave.

As is so often the case with headlands, there are two possible routes to take to round Cape Sable, an inshore and an offshore route. Your choice will largely be dictated by weather and visibility and I for one would not be keen to try the inshore route in anything other than perfect conditions, for obvious reasons if you look at the chart.

We weighed up the options and decided to use the offshore route on this occasion as our time to arrive off the Cape would be around midday when the wind tends to pick up, and we didn’t want to be anywhere too close to the shoal water inshore if we were late arriving for slack water.

Our companions, faster and bolder, went for the inshore route and were soon distant specks. It looked like they had made the best choice, but we steadily watched our boat speed rise until we were clocking double figures and the gap ceased growing. By the time we were all safely around, there was nothing much in it.

Within an hour the wind filled in as predicted and before too long we were busy tucking reefs in and blasting northeast towards Shelburne, with Cape Sable safely (and thankfully) well astern.

A Changing Coast

Once around the Cape the mood of the place begins to change. Not only are the tidal streams far weaker, the coast is less rugged, more wooded and has an altogether gentler appearance. It’s certainly very different from the austere boulder-strewn shores around Yarmouth, although it still retains a wild and remote feel.

Very appealing, in fact, and as we tacked up in the approaches to Shelburne we were feasting our eyes on lovely wooded McNutt’s Island on the port hand side of the entrance. With the wind now fresh from the north, Shelburne was still a good couple of hours up the river, and with evening approaching we scanned the pilot for somewhere to stop off for the night. Noticing a fine-looking spot on the chart on the western side of the island, we decided to go and check it out.

Dolce Far Niente

Skirting around a long sand and boulder spit that would provide excellent shelter from the north, we entered a broad bay, dropped our hook off an old and seemingly abandoned wharf and settled down to meet the neighbours.

Within minutes three white-tailed deer cautiously emerged from the trees to join the party out on the spit, where eiders murmured, cormorants dried their wings, and surly greater black-backed gulls quietly surveyed the area for opportunities to cause mayhem.

Ungainly herons clattered down into the trees along the shore to roost and in the distance an owl softly hooted, welcoming the end of the day and the hour when the island would become its own domain. Nice place, we agreed.

This was an impression that was only heightened the next morning, when we launched the dinghy and set off to explore ashore. Tying up at the old wharf, we wandered into the interior, following a dirt track used to service the light on the southern point and the few summer homes that still remain on the island.

Some local prankster had taken it upon himself to enliven the place by adding a series of comedic signboards along the way to remind us that we were in hunting country, but neither sight nor sound of hunters was evident to disturb the total peace.

So we slowly meandered down to Hagar’s Cove at the southern end of the anchorage and out on to the long spit that shelters the bay from that direction. Out on the shingle on a benign and sunny day it was hard to imagine what it must be like here in winter, although the storm-tossed debris high up on the bank provided a clue.

On our way back to Pèlerin a large barred owl glided silently through the trees across the path, pursued by a truculent crow. We wondered if the owl was perhaps our balladeer of the night before, brutally aroused from his daytime slumber by this noisy aggressor, itself enraged from a lack of sleep.

Such was the sum total of activity on McNutt’s Island that day, with not a soul in sight, apart from a few insects that buzzed sleepily around us as we hiked along the trail. Perhaps it was through subconscious absorption of the general atmosphere of dolce far niente that we felt prompted to row quietly back to our floating home for a long afternoon nap.

A Just Reward

Our time in Yarmouth had been wonderful, but with the constant damp chill of fog while we were there, we had been very glad to have our newly repaired Webasto heater working. Here at McNutt’s Island that never felt necessary and we settled down for a few days to just soak up the peace and quiet in the warm, mild conditions that signified that summer had finally arrived. After a long hard slog to get to Nova Scotia, this felt like a just reward and time to slow the pace down.

And what better place to start?

Further Reading

- Phyllis’s articles on the Tusket Islands and McNutt’s Island

Colin,

Great article! We are considering crossing the Bay of Fundy later this summer. Our thought is to cross from the Penobscot Bay area in Maine, and sailing straight to Shelbourne staying far away from Cape Sable to avoid the currents. Any thoughts as to how far south of Cape Sable we should be to avoid the worst of it? Or, as first time crossers, would we be better off going to Yarmouth and then following the inshore or offshore passage to Shelbourne. Thanks in advance for any suggestions or thoughts.

– Paul

Hi Paul,

Colin is unlikely to respond, see comment guide line #3: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/11/10/aac-comment-guide-lines/

That said I have rounded Cape Sable over 20 times and can say the best source of information on how to do that well is: http://cruisingguidetons.blogspot.com/2016/11/how-to-get-books.html

When coming from Maine direct, as long as you avoid a wind against current situation in over 20 knots and maintain a safe distance outside Seal Island and the surrounding shallows you should be good. Refer to the current charts to time the rounding.

For the inside route from Yarmouth, definitely see the above guide.

John, thanks for your reply. I have been in contact with Peter re: his guide. Will purchase a copy from him once we are in Shelbourne. Unfortunately, getting a copy while we are on the boat in Maine is a bit more problematic. Thanks for your tips. We will follow Colin’s articles on CoastalPassage planning as we plan our first crossing to Nova Scotia. Great timing of the series!