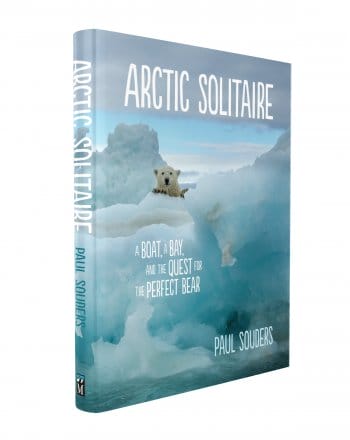

I have been uneasy about Paul Souders’s book Arctic Solitaire: A Boat, A Bay, and the Quest for the Perfect Bear ever since I finished reading it a few months ago.

But before I go on to talk more about my discomfort, I want first to congratulate Paul on his achievement. His photographs are amazing and the book is beautifully designed and laid-out. His story is gripping and he writes exceptionally well. I really wish I could be unequivocally positive about his book, but I can’t.

Risky Adventuring

And, at first glance, it is easy to understand why I would be uncomfortable, since he does the classic thing that we discourage here at AAC: buys an unsuitable boat, and then heads north with little experience in ice and spends a number of seasons beating up the boat and himself, almost dying numerous times.

And I have to admit that this aspect of his story did cause me a lot of stress. Though I’ve never sailed in Hudson Bay (Kangiqsualuk ilua in Inuktituk), I have spent a good bit of time in the Arctic, usually in a state of hyper-vigilance, very conscious that we were on our own in a remote hostile environment and vulnerable to the consequences of any negligence or mishaps.

Paul, on the other hand, took numerous risks, anchoring in open roadsteads or passaging in weather too heavy for his 22-foot motorboat, entering ice too thick for a fibreglass non-ice-strengthened boat, and approaching polar bears and other wildlife too closely (not only risking his own safety but also potentially causing stress to the animal), on a quest to make

…the best polar bear images ever shot in the 150-year history of photography.

And it does seem that our society loves this sort of “adventurous” behaviour, way more than the research-based, safety-oriented approach that we apply to boating here at AAC. You only have to look at the number of people who follow YouTube videos of newbie mariners crashing around the Caribbean (usually scantily clad and young and beautiful) compared to the number who subscribe to AAC or Practical Sailor. It’s disheartening, to say the least (and not only because I know I can’t compete in the scantily clad and young and beautiful stakes!).

Entitled Voyaging…

But there’s a more complicated aspect to my discomfort with Paul’s book that was clarified just recently, when I read “Where Not to Travel in 2019, or Ever” by Kate Harris, in the March 2019 edition of The Walrus.

In the article, Kate, an adventurer herself, reacts to the story of John Allen Chau, who approached an isolated Indigenous tribe despite their protestations that they didn’t want contact. When he wouldn’t leave, they killed him.

But, instead of treating Chau’s actions as a crime (the willful introduction of harmful germs into a population without the antibodies to fight them is a crime), many voices in the adventuring community lauded him as the epitome of a “true adventurer”.

Kate reacts to that interpretation of Chau’s actions by writing,

…what is…missing from this scenario is consent. In its place is a sense of entitlement as extreme as it is commonplace…he was just another person who believed that the world was his to do whatever he wanted in and with…

She continues on to suggest that, instead of approaching travel with a sense of entitlement and the belief that we should be able to go where we want when we want,

…how can we foster an ethic of restraint and reverence and the sort of curiosity not secretly convinced of its own superiority?

And this is what resonated for me in regards to Paul’s story, though, let me hasten to add, I don’t in any way want to suggest that Paul acted as egregiously as Chau did.

…Or Respectful Pilgrimage

The area north of Churchill, where Paul spent most of the time chronicled in his book, is populated by Inuit, who hunt and trap, and whose lifestyle has been repeatedly attacked by Greenpeace and other such anti-hunting groups.

Since Paul didn’t introduce himself to the local hunter’s association or any other officials, and he was running around in their hunting grounds in a small boat taking pictures and flying drones, a number of Inuit assumed that his

…motoring around the Bay these last few years was clearly part of a secret anti-hunting campaign to frighten off the seals, belugas, and narwhals with underwater sonar…

and they expressed their displeasure.

And, though Paul does make an attempt to see the situation from the Inuit’s perspective, overall, in my opinion, his writeup was a justification of his right to “do whatever he wanted” and not an apology for mishandling his foray into their place. In fact, he remained in the hunting grounds and continued with his previous activities after this tense altercation.

And so I can only wonder, if Paul had visited with the goal of making a “respectful pilgrimage”, as Kate calls it, instead of with the goal to make the best polar bear photographs, though that could still be one aim of the voyage, would things have turned out differently?

Crossing Lines

At the end of his last season in Kangiqsualuk ilua, feeling that he had not achieved what he hoped to, despite the risks he took, Paul quotes Robert Browning to console himself,

A man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for?

As Kate Harris writes in response to this quotation,

…[h]eaven, in this case, symbolizes noble striving at best or tragic overreaching at worst, and history is full of…casual tourists crossing lines they shouldn’t have crossed to reach it [heaven] themselves or to impose it on others.

But exactly where are those lines Kate writes about? Paul feels that his actions are justified in that he

…did my best to tell the story of one of the last wild places on Earth, a difficult land that I had grown to love.

The Inuit, though I can’t speak for them, may very well feel that they should be the ones to tell the story of their place, or at least to be consulted when someone else attempts to do so.

What About Us?

And, closer to home, what lines have John and I crossed in our voyaging? It’s hard to know. We have tried to be respectful of the cultures where we travel, but the damaging truth about entitlement is that its consequences are usually invisible to those who exhibit it.

Thank You

A sincere thank you, Paul, for giving us a copy of your book (sorry I was so harsh). And thank you, Kate, for your advice on how to voyage more responsibly.

Comments

Has anyone else read Paul’s book? Please share what you thought in a comment. I would also be interested to read what you have to say about responsible voyaging.

I haven’t read the book yet but I believe a curious mind and a gracious, gentle presence soften the impact and risks of cultural meetings. Without travel, we’d be doomed to forever wallow within the echo chambers of our own beliefs. In my opinion, travel is a fabulous freedom with a greater responsibility to not impress ourselves upon the people we meet or the Earth we traverse.

Hi Phyllis,

Very good thoughts to bring to our attention and certainly a necessary area to consider for those who wander farther afield.

For those interested in polar bears: A very good example of “non-intrusive” video of wild animals was of Polar Bears in Svalbard. Robots (think R2D2 and about as cute) followed polar bears from hibernation w/cubs for long periods. The pics/video is amazing and a great deal of fun to watch. I saw it years ago and the closest url I could now find now is: https://wildtech.mongabay.com/2015/11/personalizing-climate-change-spy-cameras-document-polar-bear-behaviors-on-and-off-sea-ice/.

The polar bears treated the robots as a curiosity and eventually their curiosity destroyed the one of the camera robots (there were a number: for snow, ice, water). You really get a feel for how these bears live and the narration does a pretty good job of describing their life and struggles.

Well recommended, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Phyllis,

I know one of the guiding head-sets in Ginger’s and my travels is that, wherever we go, we are ambassadors, if you will, and certainly representatives, for the cruising community and that our actions and choices make a difference for all the cruisers that follow. We are also aware of the same “representative” status for our nationality as we all must fly an ensign for all to see.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

A very good moral compass by which we hope also to travel in remote places…to a degree. We are strangers and have one shot at first impressions. We hope not to make them ones of arrogance, destructiveness or ignorance.

Hi Phyllis,

On another note, part of what you are addressing is in the realm of what I consider “stunts” (many of which are dangerous, show poor judgment, and should not be given display where others may experience them as representative). These “stunts”, by their very nature, are designed, at least from my observation, in part or in whole, for an audience (as opposed to someone doing something, say, for one’s own curiosity, although that motivation can also over-step good traveler judgment).

And, unfortunately, the media provides the vehicle for the audience. I cringe when I see headlines along the lines of “Youngest person ever leaves to sail around the world non-stop in smallest boat!”: and “follow daily reports and video” and wish the media would not give this person/family an audience. I believe there would be far fewer “stunts” if there were no audience.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

I have not read the book, I’d like to but I’m not sure I want to patronize bad behavior.

We see the sexy, sensationalism selling all too often, how many times do stories about foolhardy, would-be cruisers who have to be rescued from themselves making the headlines? The two women and their dogs drifting in the Pacific, aboard a vessel that appeared to have a functioning mast and sails, comes to mind, but there are countless others. While stories of epic passages that include adventure, made in safety without incident aren’t worthy of mainstream media’s attention. As a result, the general public’s view of us is often skewed at best.

Having spent time in high latitudes, including Antarctica, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Svalbard, and in close proximity to polar bears and other wildlife, I’m an avid bird photographer and these areas are a paradise for this pursuit, this story struck a chord.

As a photographer I constantly have to balance the goal of getting the perfect image with not stressing the animal. A couple of years ago, I had the opportunity to see and photograph a polar bear swimming across a fjord mouth, and then ambling up the shore, onto a patch of snow, where he promptly rolled over like a dog and stuck all four paws skyward while rubbing his back. I felt privileged to be there, and to have the opportunity to photograph it from a small boat, and doing so without intruding on his space made it all the more enjoyable. Conversely, last year I was in Mexico on a project and I watched a (professional?) photographer filming pelicans feeding while he was in the water, using an UW camera, sadly he exhibited all the wrong behavior, he had a mate dropping bait into the water on a line that he quickly pulled away from the birds repeatedly to get his shot. It went on for about 10 minutes before I yelled over to him, “what are you doing?” as if I didn’t know. I kept yelling questions, distracting them, drawing attention, making them as uncomfortable as I could until they finally stopped. It was appalling. I watched a Dutch tourist, an amateur photographer festooned with gear he clearly didn’t know how to use, stomp into the middle of an Arctic tern nesting area, and stand there for some time taking photos, with a strobe no less, as the birds dive-bombed and finally drove him off.

If nothing else, these examples of poor animal interaction give photographers a bad name.

Every wildlife photographer gets too close to a subject at one time or another, in the heat of the moment, when photographing a subject. I did it recently while photographing Mikado pheasant in Taiwan, and then I caught myself and stopped, and stepped back. There’s a big difference between that and intentionally setting out to put yourself in an animal’s (or foreign culture’s) personal space over and over again. If you see people doing this, remind them it’s not right, and if necessary shame them into stopping.

Hi Steve,

Agreed and all very nicely put.

It is indeed distressing to watch the manipulation of wild animals for our enjoyment and for profit making. Whether it is dive ops inducing manta rays or those surface ops chumming for sharks, these profit making tourist attraction activities are sometimes dangerous (sharks learn that outboard engine noise = food) and never in the best interest of the animals.

I would not think it unwise to take the position that the feeding of any wild animal should be discouraged/banned: I can think of few instances where it is the animal species best interests to be fed by humans (an emergency food drop to starving reindeer trapped in unusual snow conditions might be one example).

I applaud those cities that have banned the feeding of pigeons and might easily go so far as to suggest that the commonly seen bird feeders outside homes are unwise as well (if the homeowners want to see birds, they can make the effort to go for a bird walk).

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Thank you all for your comments.

I really don’t want to vilify Paul. Rather, I give him full credit for being brave enough to put himself out there in his book. And I am very glad I read his book, because it inspired me to think deeply about my own impact on the places and people where I have traveled, since I sincerely believe he behaved no more insensitively than I have at times.

By virtue of being affluent enough to own a boat, and by virtue of being white (as I’m sure most of our readers are, though I hope we have some diversity within our membership), I operate from a sense of entitlement. A sense that I should be able to go where I choose to go on my boat. Just as the photographers Steve talks about felt they should be able to do whatever it took to get the shot that it was their “right” to get. (Thank you for being honest about when you also crossed the line, Steve, since we all cross the line at times.)

But what do the people where I travel actually think about my foray into their territory? In Greenland, dock space is very limited. When we tie up somewhere, by definition some Greenlandic is not able to tie their boat up there. Maybe what I perceive as their self-possession is actually resentment. And what about all the other things I do that I don’t even realize have an impact radically different than what I am intending?

However, neither am I implying that we shouldn’t travel. I agree with Paul Padyk on that. But where, when and how are all things I am going to think about much more deeply in the future.

Hi Phyllis,

I think your lauding Paul’s book for its stimulation to consider these issues in general and to examine one’s own personal impact is warranted, but I doubt you have acted with the same degree of insensitivity.

My thinking is, generally speaking, two-fold.

First, I believe it possible to be aware of how you are received in a new community, even if you do not share a language: but you must want to tune in to those indications and make it clear that you want to be told of any transgressions. I suspect that you and John do as I do, when I raft up on a fishing vessel (or tie up on a wharf): I search out the owner and the harbor authorities, I ask if there is a better place to moor, I stay with the boat unless informed that the fishing vessel is there for the day etc. (In other words, I convey that I do not feel entitled to a place on the wharf or in their community.) All these actions tell the community that you want to respectfully visit, not be in the way of their making a living, etc. and when we feel we receive consent to stay, we relax and settle in. As we become better acquainted with the community and receive an interest to participate in the community, does not always happen, we are very pleased.

Secondly, I believe that motivation is important: in your description, Paul’s motivation was a competitive intrusion for personal aggrandizement (I will capture the best picture polar picture ever) and far from a respectful pilgrimage. While we can tune into the community’s reactions to out visit (and should), but we should also look at our own motivation for doing what we are doing, for visiting the places we visit.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Steve,

Agreed and all very nicely put.

It is indeed distressing to watch the manipulation of wild animals for our enjoyment and for profit making. Whether it is dive ops inducing manta rays or those surface ops chumming for sharks, these profit making tourist attraction activities are sometimes dangerous (sharks learn that outboard engine noise = food) and never in the best interest of the animals.

I would not think it unwise to take the position that the feeding of any wild animal should be discouraged/banned: I can think of few instances where it is the animal species best interests to be fed by humans (an emergency food drop to starving reindeer trapped in unusual snow conditions might be one example).

I applaud those cities that have banned the feeding of pigeons and might easily go so far as to suggest that the commonly seen bird feeders outside homes are unwise as well (if the homeowners want to see birds, they can make the effort to go for a bird walk).

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

My wife the wildlife rehabber would agree: Ducks in particular will die eating bread, which they can’t easily digest. As for marine life, some of us did not shed many tears over such “popularizers” such as Steve Irwin’s untimely interaction with a stingray; one suspect he was annoying the poor thing.

Dick:

Eliminate bird feeders… what is this world coming to;-) My wife shares your thoughts on bird feeders, she says it teaches the birds to live on hand-outs, which isn’t good for them. I counter, referring to the feeders as “forest and renewable energy offsets” arguing that our home and yard used to be a forest, we’re making up for its loss. We’re also offsetting for the millions of birds that are killed annually by wind turbines (and domestic house cats, which are technically an “invasive species”).

Hi Steve,

“Forest and renewable energy offsets” I love it! And domestic cats should definitely be kept as in-house pets: at least in the forested suburbs, perhaps not on a farm.

I see us as largely on the same page, but I will use our dialogue to flag a pitfall that I see many in our world falling into: were we to argue about bird feeders, we might not act in our many areas of agreement. Or to put another way: sometimes the enemy of getting things done is arguing about where to draw the line.

BTW, aside from the feeding aspect, I also look askance at bird feeders because they are manipulating wild animals for our pleasure and, furthermore, undermining our motivation to get out and see the birds in their natural habitat.

My best, Dick

Dick:

But a healthy difference of opinion, and this is applicable to the forum, articulated in a positive, constructive manner, is the very spice of life, we don’t need to reinforce all that we agree upon, that list would be far too long and boring, in order to debate an important tissue. I think the important part is to keep differences civil and not take them personally, that seems to be where we as a society have gone astray, IMO.

Now, back to bird feeders, unlike polar bears, which live in a wild environment and hopefully are not overly affected by direct contact with people, the birds in my backyard are habituated to people, millions are killed by the actions of people every year, the aforementioned wind turbines, being hit by cars, eating pesticide etc, so again bird feeders are a small way of offsetting what humans have already altered.

Birds in more wild environments may be a different story, Atlantic gannets, puffins and guillemots, but few are setting up feeders for them.

Hi Steve,

Agree about the importance and fun of sharing differences when not taken personally and, indeed, it is one of the spices of life (and a superb way of continuing to learn and grow). And agree: birds (indeed many animals) who share environments with us humans have taken a beating and deserve some TLC.

My best, Dick

Great thread. I will say why can’t we have bird feeders and go out and look for and find birds too? Our city parks are part of the Great Texas Birding Trail and they used to have feeders too. The park feeders are gone, but we do have a couple in our back yard. It does not deter us from spending many Saturdays walking our trails in search of birds. Conversely, some residents started feeding the turtles in the park bread at one of the bridges across our creek. Lately, there were about two dozen turtles waiting for their handout at the usual time. My wife did some research that indicated the bread was unhealthy and of course the behavioral manipulation was not appropriate either. She spoke to the people feeding the turtles about this and they agreed to stop. Park turtles do not compare at all to wilder things like polar bears or even pelicans, but it does illustrate that most people want to do the right thing when given the proper information.

Hi David,

If your wife’s approach to the turtle feeders was as pleasant as your posting, I am not surprised she received a positive response. And I certainly agree there is a continuum here.

My best, Dick

Just to put the issue of whether bird feeders are good or evil in perspective—–

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/sep/27

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/23/destruction-of-nature-as-dangerous-as-climate-change-scientists-warn

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/feb/10/plummeting-insect-numbers-threaten-collapse-of-nature

*Earth’s sixth mass extinction event under way, scientists warn

*Plummeting insect numbers ‘threaten collapse of nature’

*Of all the mammals on Earth, 96% are livestock and humans, only 4% are wild mammals

*Since the rise of human civilization 83% of wild mammals have been lost

*orca-apocalypse-half-of-killer-whales-doomed-to-die-from-PCB contamination.

Hi Steve,

Agree about the importance and fun of sharing differences when not taken personally and, indeed, it is one of the spices of life (and a superb way of continuing to learn and grow). And agree: birds (indeed many animals) who share environments with us humans have taken a beating and deserve some TLC.

My best, Dick

An interesting thread, and a tough one. One of my sailing exploits – a solo Atlantic Circle in a thinly-disguised quarter-tonier – might be considered a stunt, so I don’t know how to consider this. Taking a 22-foot motorboat to the Arctic isn’t something I’d consider, but most of you wouldn’t consider what I’ve done, either. If I’d waited to get what most contributors to this blog seem to consider necessary for ocean cruising, I’d still be waiting; I went with what I had, and the experience and confidence to think it would be okay.

The stunt aspect is something else, though. I didn’t make my voyage for fame, fortune or to break any records. It was for me. I like to ride fast on a motorbike, but I don’t care for spectacular wheelies! I have to agree with others here: I too cringe when I see children setting off on circumnavigations. However, I also remember Robin Lee Graham’s book “Dove”: a stunt for sure, yet also a damn good yarn with some lessons to give.

I guess I’ll have to read this one and make my own mind up!

Thank you so much for your comment, Jim, because I totally agree with you that this is a complicated tough topic, and I would really like to hear your thoughts once you have read Paul’s book. I am a very anxious person, especially when sailing on the southeast coast of Greenland! And, so, maybe my anxious nature led me to misrepresent his voyages in my article. Maybe you would have a very different take on his voyages than I did.

What I don’t think I communicated very well in my article is that Paul did not take what he did lightly. He worked incredibly hard to achieve his goals for his voyages. He did not approach his voyages as stunts. He is an artist who wanted to make his art in that environment and he did it in a way that he could be self-sufficient, rather than relying on others to ferry him around, and in a boat that he could afford.

So where is the line on the other side of which lies “stuntness”? Or the line on the other side of which lies “disrespectful” voyaging? Tough questions but I think worth thinking about as we plan our voyages.

Hi Phyllis,

a lot of my thoughts have already been reflected in the previous comments so I’m not going to repeat them, just one basic voyaging principle that we might consider – “my own freedom ends where the freedom of the next starts”, and this naturally includes wildlife as well. Sport divers have a similar rule – “bring nothing than curiosity, leave nothing except bubbles”. This pretty much sums it all up.

And, finally, “because I know I can’t compete” – oh Phyllis, just look deep into Johns eyes and you’ll notice that you very much can.

I’ve added Arctic Solitaire to my backlogged reading list, thank you for bringing it to my attention.

Phyllis’ thoughts, and subsequent discussion, brought to mind a book I recently enjoyed: “Across Islands and Oceans” by James Baldwin. The interactions Baldwin candidly describes in his account of his mid-80s circumnavigation (on a Triton!) relate to this thread, and struck me as reflecting a very healthy philosophy regarding how to manage the effects of our serial intrusions into worlds where we, as cruisers, are transients. Baldwin made it a point to walk across every island he stopped at, and interacted, as well as he could, with the locals and *their* environment. His growing awareness of how much bigger the world and humanity are than the perspectives he left Michigan with is uplifting. From the forward:

“While there turns out to be no perfect plan, I learned some things on this imperfect voyage that shaped my life in the best ways possible. Beginning with a world-view as small as my boat left me with no room for passengers. Alone on the oceans, I learned how to live in isolation. Hiking across the islands with near-empty pockets and well-worn boots, dependent on the generosity of the inhabitants, taught me how to live in society. What richer reward for a passage of two years?”

Comparing the experiences these two young men tell of should be interesting.

Hi Phyllis and John,

Despite all the earlier explorers writings, heavy boats, groundings, crushed boats, sickness, cannibalism, and wild egos, Paul actually survived, and came back with beautiful pics. Clearly a driven photographer, not your usual cruiser, he took a small light boat, worked the shore, often in the dinghy working hard for special photos. He made multiple ill-fated trips/adventures, and came home with not only stories, but great photos. I was impressed, what a lot of work. I though the book was one of the most honest and personal I’d read in a long time. Paul tells so many realistic stories about his mistakes, screw-ups, fears, overstocking, un-prepared planning, er, lack of, that I was worrying, understanding, and enjoying the book like it was a Twain or Bryson adventure. Yes, I do consider it a serious cautionary tale, and understand your concerns.

Thanks for the comments, Lee

So glad to hear from someone else who has read Paul’s book. Thank you for highlighting another aspect of his story that I didn’t include in my article—just how hard he worked and how exhausted and overwhelmed he felt much of the time (it’s impossible to include everything in a short piece, so I always feel, after I’ve written something, that I missed so much other important stuff!). The fact that we have so much to write about is a testament to the fact that Paul wrote a very interesting book.

Is it possible to visit as a respectful Pilgrim where you don’t speak the language? I want the answer the be yes and welcome examples. However I fear that the assumption I can get by with just English creates a foundation of entitlement that flavours everything else.

If the answer to this question was “no” it means one can only travel to places where the inhabitants speak English, that smacks of sheltering and narrowing one’s view, and in itself could be considered entitlement. That would also be terribly limiting in so many ways.

I’ve traveled to many places, by sea, air and land, where few if any speak English, rarely have I felt it was off-putting to the locals, especial if you take the trouble to learn a few words or phrases in the native language, in fact in many cases they admire those who are unafraid to leave the comfort of the “English zone”.

I travel in China and Taiwan often, at times I’m the only westerner in an entire hotel, sometimes the only English-speaker, I find that sort of immersion the most interesting and rewarding type of experience, I actually prefer it, and it broadens one’s view, which is one of the reasons for going cruising.

As an aside, English is the official language of aviation and maritime communication, would that too be considered entitlement?

Showing deference and respect for the culture goes a long way even of you don’t speak the language. In Taiwan, for instance, there is a very definite means by which one shares one’s business or credit card, holding it by two corners, with two hands, using thumb and forefinger, palms up, with the card’s text facing the receiver. Taking the time to do this speaks volumes to the person on the receiving end.

Hi PD,

I agree with Steve completely. I have little language facility and not speaking the local language was a worry of ours in just the way you voiced your concerns. In one notable season we visited 7 different languages. Operating in a very similar way to what Steve describes we met with similar accepting responses from the people we encountered. I think it is always possible to find little ways to show you are respectful and not operating from an entitled position.

That said, I will observe, to my lasting disappointment (I have a growing list of skills to garner in my next life and one of the foremost is a language facility), that not knowing the local language puts a “ceiling”, if you will, on how close to a community/country you can become, but I think that respect and the feeling of dealing in good faith by and large transcends language.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Dick:

Re. language, I agree, it has left me feeling as if I could only delve so far into the culture of other civilizations while cruising. I recently had a detailed discussion with a taxi driver over a 20 min ride in Taiwan, covering everything from politics to food, he talked the whole time and it was very enjoyable, and neither of us spoke the other’s language. He had an electronic stand-alone audio translator that was remarkably accurate (it referred to itself as a “translation machine”), it enabled us to converse freely. I find that many people in Asia who conduct commerce with the public have these, even in rural areas. They are not expensive. Of course I use Google translate, and I use the visual translation feature of WeChat to translate signs and labels. Times have changed, the language barrier is not what it once was while cruising. I’ve had a few amusing experiences with these, recently I was buying jewelry for my wife while visiting Gulangyu, an island near Xiamen China. The saleswoman, who was incredibly helpful, kept asking, via a translation app, if I took a shower, it was a hot day and I had been walking a lot so I was wondering if I smelled, ultimately what she was saying was, “don’t get it wet”. Now, if only there was a version that could translate a Scottish brogue.