Last night, for the second time in less than a week, we got hit with much stronger winds than forecast, generated, we think, by the proximity of the Greenland icecap.

The first time, we were hit with gale force (34 to 40 knots) winds, gusting higher, just after dropping Grete, our scientist, off at a village in a flat calm. We worked our way into a tiny “U” shaped cove on the lee side of an island, dropped the anchor in 60-feet (20-meters) of water as close the head of the cove as we dared, and dropped back into deep water. The anchor held after one heart stopping jump as we were caught broadside by a 50-knot gust.

We were secured and away from the ice but far from safe since any shift in the wind that was howling directly out of the cove would put us ashore, so we launched the dinghy and put in a shore-fast to each side, slightly aft of the beam, giving us options no matter what the wind did and a backup in case the anchor dragged.

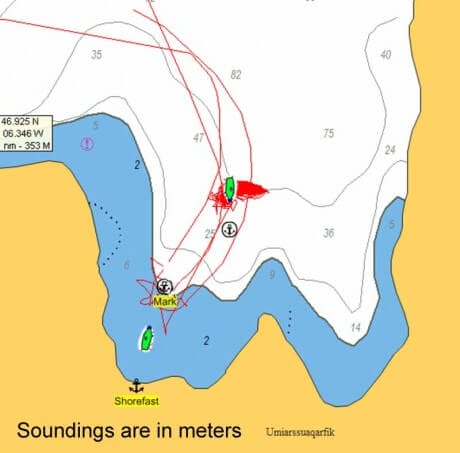

Yesterday, in anticipation of a forecast gale, we had dropped the anchor in a larger cove (see map above) that would be in the lee, backed in toward the shore, and put in a shore-fast off the stern. Thirty minute’s work, and we felt snug, well away from the ice sloshing around further out and prepared for the forecast winds.

But when the winds reached strong gale (41 to 47 knots) with much higher gusts that came first from one beam and then the other, the boat was being slammed back and forth placing huge loads on the anchor and shore-fast. Everything was holding, but if either failed we would have been on the rocky shore in seconds and the boat lost, and there was no knowing how much worse it was going to get.

So we made the very hard decision to slip the shore-fast, haul the anchor, and move further out in the cove where, although it was blowing even harder, and the water was a lot deeper at 100-feet, the boat could swing to the gusts and we had a good half a mile to leeward to sort things out if we dragged. (At this point, the strong winds had blown the ice away to leeward.)

The point of all this is that in the first case, putting in shore-fasts was the right and safest thing to do and, in the second, after the conditions changed from the forecast, it wasn’t—just another time in offshore voyaging where there is no one right way to do things. In each case our decision was driven by what set-up would give us flexibility and the most options if something failed or the conditions worsened.

And the second situation reinforced the way our thinking about anchorage selection has evolved over the years: Although being close to shore when it is blowing can feel more secure because you get more lee, moving out into more open water can often be safer because you have more time to react if anything goes wrong.

There is no question in my mind that moving away from shore was the right thing to do. You were originally less than one anchor-length away from shore giving almost no time for corrective actions if dragging started. Instead you moved on your own terms in safety to a much safer location. Dropping the anchor at the new position in the center of the 25 meter contour looks about as perfect as possible.

I always assume whatever choice I make will be wrong and may need to be changed. You made your decisions and then made changes when needed. You and your boat came through unharmed, so in my opinion you made the correct choices.

It doesn’t take high latitude voyaging and challenging conditions to put the boat at risk. Actually the everyday attitude and gear favored by many cruisers does the job quite adequately!

Case in point: This spring I joined a boat in Panama heading north to Cuba. 61 foot of ultramodern cruising design, Seizure Furl main, 8’6″ of draft, and an owner who had been a major force in west coast offshore racing. About 150 miles to the east of Honduras is a place called Quita Suenuo (stop dreaming!) reef. Not a grain of sand above the surface, the only landmarks the hulks of huge freighters sticking up at 45 degree angles where they had come to a tragic end. So our owner decided it would be a cool place to stop overnight.

After picking our way through ten miles of coral gardens to leeward of the reef face we came to a large sand patch at about 3 meters depth. Skipper chose to set the 55lb Delta (barely adequate for a 36′ boat to my way of thinking) in this sand patch and lie back with the gentle trade wind breeze. Refused my suggestion to set a stern anchor. Did I mention that the skipper had racing trophies that certified that he knew more than anyone else? So here we are in the middle of the ocean, with the ghosts of dead sailors all about, needing only for the light trade winds to die to put our 8’6″ bulb keel permanently in the sand, send two million dollars of epoxy and carbon to the boneyard, and put us adrift in the most remote part of the Caribbean.