See if you can count the number of shorefasts (click to enlarge).

In Part 1 I covered the physics that govern shorefasts. Now let’s move on to some example configurations and then some fun stuff: tips, tricks and hacks that make putting in shorefasts safer and easier.

And, yes, I deliberately put the fun tips at the end so you would have to read through more theory to get to them—no cheating now.

Seriously, do read carefully. I learned a huge amount, as well as trashing several of my long-held assumptions, while putting together the diagrams for this chapter.

Never Two Points

But, first off, let’s expand on why we pretty much always need more than one shorefast and an anchor.

(There is one exception, which I will get to later.)

I’m guessing that most of you already figured it out from Part 1, and that just goes to show the importance of properly analyzing these things, rather than relying on common practice, like I did when I used to use just one shorefast and an anchor. (I like that excuse better than the other option: I’m a dummy.)

Anyway, the reason is that there are two vital requirements to make shorefasts work safely:

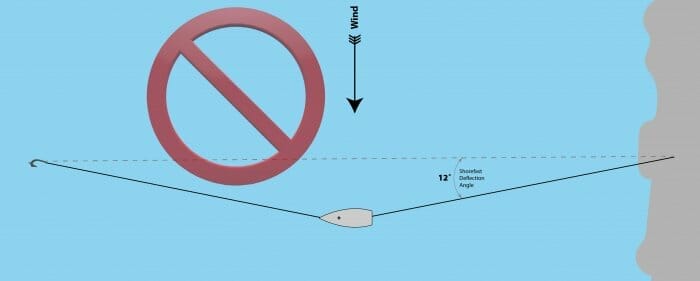

- We need to avoid small shorefast angles, like that in the graphic above.

- On the other hand, we need to take slack out of the system to reduce impact loads from the boat slamming back and forth caused by multi-directional gusting—common in small anchorages.

So let’s look at adding more shorefasts and/or anchors:

Hi John. Love your combination of theory and practise. One question tho: after having put out the anchor one of you gets in the dinghy to go ashore. The other, you say, keeps the boat in position. Could you elaborate on what position? I asume it would be done by reversing?

Hi Bob,

See the linked article on prop wash and walk in further reading for the fundamentals of moving a boat around without putting any way on.

Dear Phyllis & John

You have no idea how disappointed I was when I found I couldn’t read your new post in AAC today because my subscription expired.

But at 8:06 AM, my subscription through Paypal renewed automatically. And now I can read your posts again! Yay!

(P.S.: “Experiment in Survival” by George Sigler, is an excellent book on survival at sea.)

Best wishes,

Charles

Charles L Starke MD FACP

s/v Dawnpiper

Hi Charles,

Glad the billing kicked off in time. It just drives Phyllis and me crazy that even after a member fixes an expired credit card they have to wait several days for PayPal to actually process the outstanding charge. Bottom line, PayPal had a monopoly for far too long!

Hi again Bob,

That chapter in the Docking Book will give you the basic concepts. Perhaps, if people are interested, I could do a chapter on moving the boat around once we have an anchor down since it would also be useful when going stern to at a wharf as often required. Too much for a comment.

John, do you see any value in a shorefast situation with surge and storm-force winds of (fuel supply considered) leaving the engine on in neutral or dead slow ahead to ease the strains, or to be prepared to ease the strains, involved on the setup?

Hi Marc,

No. Same reason it does not work at anchor: you just can’t reliably apply the power in any useful way since even in a full on storm the wind varies a lot in both velocity and direction.

Also remember that by far the largest loads are when the wind hits on the beam, so no way to offset that.

Hi John and all

There are three circumstances where I use shorefast lines and each requires a different technique to run the lines.

1. Good holding and very windy but with trees to hide behind if you can get close enough to them – Patagonia is the classic example. Here I use a stern anchor and two to four shorefast lines.

2. Good holding but no trees in a cove that has insufficient swinging room to anchor – Greenland, northern Labrador, Falkland Islands for example (kelp can be a problem in these areas). I use a bow anchor and as many shorefasts as seems necessary – at least three plus the anchor. Using a second anchor to limit the swinging room without running shorefasts also works but almost invariably end up with the rodes twisted – a foul hawse.

3. Very poor holding such as in Antarctica with its ice-scoured bottoms. Skip Novak, Jerome Poncet and others use shorefasts because they have no choice; an anchor will not hold in many Antarctic Peninsula bays. In this case I use an anchor as a dead weight to hold the vessel temporarily while I run as many shorefast lines as possible. This limits a single hander to moving in settled weather only.

In Patagonia I almost always used shorefasts because that is by far the most comfortable way to secure for the night, even when there is room to swing to anchor. The winds are strong and almost always have a westerly component. It is easy to choose a cove with protection from that quadrant then haul up close under the lee of the trees to get out of the wind.

Greenland and Labrador are more problematical as there are no trees to hide behind and the wind is more variable. Fortunately the wind is seldom as strong as in Patagonia. My preferred option is to lie to anchor if there is room to do so. If there is not, I drop the bow anchor at the windward end of the cove, drop back, set the anchor then run the shore lines at my leisure. There may not be room to swing when the wind shifts, but in the interim it is unlikely the gusts will vary in direction enough to put the vessel ashore before I run shorefasts.

Antarctica is the hardest one to deal with – there is little protection from the wind (and often a lot of wind) in many anchorages and the holding is usually very poor. There is little running water in Antarctica to bring silt or other sediment into the sea so the bottom is generally bare rock. Ice is often an issue too. Shorefasts are the only solution, but not always easy to run. Each bay and cove has its own peculiarities, so the time spent on reconnaissance is vital.

The technique I use to run shorefast lines is only a minor variation on John’s. The chief difference is that I frequently use a stern anchor as my primary anchor and drop the bower underfoot to temporarily hold the boat while I get the shorefast lines run. This system works well when using shorefast lines to pull the boat into the wind shadow of trees in Patagonia

Here is how I did it in Patagonia:

1. Stooge around under engine and decide how I will arrange things.

2. Launch the dinghy, put it on the hip and flake a 100m (rarely 200m) shorefast line into the dinghy with the end of the line (which is of course on the bottom of the pile) sticking out so I can find it later. The bitter end is secured to the big boat.

3. Motor into the cove and drop the stern (kedge) anchor typically 40 or 50 metres from the final berth. This anchor is usually a 35 lb Manson Supreme on rope with only a little chain. I have a fairlead on the transom to make this easier.

4. Motor into the berth paying out the anchor line as I go. At this stage everything is controlled from the cockpit – engine, steering and anchor, which is critical when single handed. The common yacht practice of letting go the bow anchor and backing in towards the shore is difficult or impossible when single handed and probably not desirable if fully crewed. There is the difficulty of handling gear from each end of the boat, the poor manoeuvrability of most yachts astern and if things go wrong it is the rudder and propeller that take the hit, not the relatively robust front of the keel. And if backing into the berth it is likely that the companionway will end up facing into the weather letting rain in unless the washboards are kept in place.

5. Once in the berth belay the kedge, engine into neutral, then nip forward and drop the bow anchor on very short scope. This is to steady the bow while I get the line ashore and is not expected to hold the boat for long.

6. Leap into the dinghy and row the windward bow shorefast ashore as quickly as I can. I do this in reverse to John’s method – paying the rope out from the boat towards the shore rather from the shore to the boat. I don’t have an outboard engine and find it easy to row with the line paying out over the dinghy transom. If using an outboard motor it is probably better to use John’s method, paying out over the bow starting from the shore end. This keeps the engine further from the rocks.

7. On reaching the shore I tie the end of the shorefast around my waist (that’s why I left it sticking out), throw the dinghy anchor up the shore and scramble to my chosen tie point. Tie off the shorefast line.

8. Row back to the boat as quickly as possible.

9. Take up tension on the shorefast and belay. There are still several more shorefast lines to run, but once the windward line is secure the rest can be done in a more leisurely manner. There are a few busy minutes when things need to be done quickly and correctly but with practice the process becomes less stressful.

Hi Trevor,

Thanks very much for a great comment that fills in most all of the gaps in my knowledge.

To others: make sure you read Trevor’s comment with care and not just scan it, there’s a huge about to be learned there.

One caution, you will note that Trevor ties the shorefast around his waist with the other end tied to the boat and I totally get why he does it that way. But this works for him because he has huge experience and probably an almost sixth sense for the wind and how his boat will react. Also single handers just have to take more risks to make things work.

But for the rest of us, this could be a really dangerous thing to do, particularly in a cove without the protection of trees, since if the boat suddenly swings to a puff of wind one could be dragged across the rocks and into the water. So, I would suggest that our way of attaching the line to the boat last is a lot safer for most of us, particularly those new to shorefasts.

Hi John,

Great writeup, as always, and thanks to Trevor for the added value! I’ll try to contribute with my experiences. It’s the same topics as in my comment in part 1, but I’ll go in more detail.

Mostly when thinking about shorefasts, they are seen as a way to stabilize the anchoring position, and the boat is kept at a good distance from the shore, “to be safe”. (More on that later). I use shorefasts only to get the boat close enough to land to step directly ashore from the deck. Since I’m a Norwegian, I prefer the “Scandinavian moor”, with the anchor from the stern and the bow to the shore. This is normally used in nature, where the coast in Scandinavia is mostly smooth granite bedrock.

The “Mediterranean moor” is the opposite, anchor from the bow and stern to land. This is meant for mooring at a dock, not close to a natural shore line. The Med doesn’t have as many locations with a protected coast line that is deep enough close to shore. Scandinavia has an endless supply of that. I strongly prefer the “Scandinavian moor” over the “Med moor”, because the former allows me to approach the shore without fear of damaging the rudder, I can get much closer, and because it’s much easier to manoeuvre precisely in windy conditions. As described in the previous comment, my procedure is roughly as follows:

1. DECIDE LANDING. I go to land where we want to be, to check it’s suitable to get close enough to walk ashore from the bow there. I also look for suitable shorefast attachment points in various angles. It’s smart to be picky at this stage.

2. DROP ANCHOR. I go out again, spend some time considering exactly where to drop the anchor to get a good bottom, plenty of scope and correct pull angle to suit the chosen landing spot. Electronics can be a good help with this.

3. PULL-IN SHOREFAST. I go back in to the shore, normally just letting the anchor rode quite loose. If i’m alone, I set the rode and have an engine at slow fwd and go to the bow. I go ashore, set a single slack shorefast. Then I decide the anchor tension that makes it reasonably easy to jump ashore from the bow, and still tight enough so the boat can’t hit anything if pulled in hard. This shorefast is normally moved a bit and adjusted when all else is set, to facilitate pulling the bow in for stepping on/off. When this line is not pulled, the boat goes out quite a bit. When stepping on and off a lot, like unloading grill equipment, this line is tied tight, and then released immediately when finished.

4. ANGLED SHOREFASTS. The boat is now roughly in its intended position, but it’s vulnerable to wind. I need to add shorefasts to get good angles and a precisely locked sideways location. Shorefasts from the bow and angled as far apart as possible so that they don’t pull the boat inwards much, just controls the sideways position. These angled shorefasts normally end up at a great angle to the anchor, often 60-80 degrees. This is a key advantage from being very close to the shore. It’s possible to reduce the added anchor tension a lot.

5. EXTRA SHOREFASTS. Sometimes I also bring a long angled shorefast to the stern, to keep the boat more aligned without pulling too hard on the anchor. This can make a difference, but is mostly used to position the boat relative to other boats or stones under water.

6. SLACK SYSTEM. It’s important for this to work that there is enough slack in all the lines when there’s no load from wind etc. The boat position should be defined by line directions rather than line tightness. The lines should give clearly defined limitations for where the boat is able to go, and otherwise be fairly loose. The first hour after mooring this way I spend observing and mostly releasing the various components until it’s good. Often I move or add a shorefast. I normally end up with a boat that can move max ½ meter (1,5 feet) sideways at the bow, about 2 meters (6-7 feet) sideways at the stern and about 2 meters (6-7 feet) longitudinally, towards and away from land. At night I normally pull in a slight bit like 30 cm, (1 foot), on the anchor and release suitably on one or more shorefasts, to sleep well.

The Med moor also mostly puts the boat very close to the pier, making it possible to get good angles. Normally 4 shorefasts are used. One straight in from either side of the stern and one long crossing spring from either side of the stern to a point well outside of the boat width. This gives good angles and the completely locked sideways positioning needed in full Mediterranean harbours. Quite often there are mooring lines from the pier to be lifted by the boat so no anchor is needed.

Summing it up, my take on it is that shorefasts are best for getting very close to the shore, and normally not a suitable strategy for added safety. Counterintuitively, I think keeping the boat very close to land makes shorefasts safer and better than using long shorefasts to keep the boat further off. Close to land you can get far superior angles by directing them sideways so they don’t tension the anchor rode much.

The “Scandinavian moor” is very nice to use in suitable locations and conditions, and reduces some of the inherent problems with shorefasts. Still, it won’t remove the problems. Shorefasts add complications and risks we need to monitor, thus it’s mostly for protected spots and rarely suitable if the boat is left alone.

When I go places with a boat, I love the sailing and views from a distance, but my main pleasure is to stay close to what I explore, which is land. Scandinavian moor is a bit like having a garden around your house. You can just walk out the door and you’re immediately in it, anytime you want. Zero hassle. Staying further out, so you need the dinghy, is like having that same garden, but you need the car to get there.

Hi Stein,

Great explanation of the Scandinavian system, thank you.

Good point about the loads being lower because of being closer to the shore. I’m pretty sure that’s right although of course they will still be higher than with and anchor or for that matter with a four point. But of course two anchors for a four point will not work often because it would be very inconsiderate to take up so much room that others could use—not the Scandinavian way!

And very good to make the point that this is a strategy to have some fun and get close to the shore, not an increase in safety over anchoring.

Hi Stein,

That sounds interesting, and fun, for calm situations.

I hope I’m not hijacking this thread with these questions.

How do you secure the anchor to the stern? Do you use a bridle to cleats to even it out? Do you have a windlass of some sort? Also, I have seen pictures of Scandinavian mooring where they use a reel with some kind of webbing material. What are you thought on those?

Thanks

Ralph

Hi Ralph,

I’d agree that mooring very close to land is absolutely for calm situations. However, that’s easy to find most places in Scandinavia, no matter what the weather is like. The archipelagos makes it possible to sail in protected waters along much of the coasts. Innumerable islands and small coves. Protected locations can almost always be found. Also, the weather is actually mostly quite nice and warm, in the southern parts. In the arctic parts that’s very different, but there are islands all over the place there too.

Since the locations and conditions are protected, the gear normally doesn’t get too challenged. Quite poor equipment and practices will mostly do the job. I prefer to do it better, though… How I do the anchor depends. Mostly I use a fairly large Fortress with a rope rode. If it’s deeper or hard bottoms, I use the bower with chain and all. Drop and set it from the bow. Transfer the rode to the stern with a rope under the bridge deck. (Catamaran).

The webbing on a spool is a Swedish product. Ankorlina is the name. The marketed advantage is compact size and easy handling. It only works on relatively small boats. I see no good point, and prefer normal rope. I have a small roller on the aft deck to pull the anchor by hand. Since it’s a pure rope rode, I can use the spinnaker winches to pull it in, but that’s never been needed. The aluminium Fortress anchor is around 5 kilos…

I don’t normally use a bridle on the stern anchor. I rather pick which side of the stern is the most useful. The boat is held in position by the combination of the shorefasts and the anchor, with the latter mostly left with the job of limiting how close the boat can go, not how it yaws. If I for some reason could only have one shorefast, I’d probably want to have a bridle on the anchor. With our 7 meter beam, it would make a difference.

Perhaps worth mentioning is that we have several bolts and other metal objects meant to get a grip in cracks in the rocks. ALso a good hammer. That’s important most places.

Scandinavian moor really isn’t very hard, if you take your time observing, thinking and adjusting. Most local boaters skip several of those steps and rather hope nothing unexpected comes along. They drop the anchor haphazardly, run one main shorefast plus normally one more to the side, then have a drink. A recipe for vulnerability, but normally nothing happens.

Thanks

Ralph

Hi Ralph,

I used polyester/Dacron flat “rope” on a reel for years in the Med. It was particularly nice to use as I would swim to shore with it tied around my waist coming off the reel easily and secure it ashore. (Later when sorted and dinghy launched, I would better secure the shore connection: chain around rock or ensure the tree was protected from chafe.) This was particularly nice as it did not seem to sink (or quickly sink) so it just scooted on top of the water. Polyprop would also float, but I just found it too poorly behaved to cope with and in those days, HM line was new-ish and very pricey.

This area had particularly calm nights and very cozy anchorages generally: with any unsettled forecast, I would back up the flat rope with nylon 3 strand shorefasts to either side.

The one challenge I remember was how hard it was to secure it to the cleat as it readily slipped: like the very slippery HM line John refers to (unlike rope there was no “bulk” to get squeezed tight and the flat profile would slip underneath). I resorted to the Lighterman’s hitch (great for bollards and winches) which then worked well.

Its flat surface also found vibration harmonics at certain wind speeds. Not a big deal during the day, but at zero-dark-thirty bothersome.

Out of warm swimmable waters, it still comes in handy occasionally as it just slips out easily when rowing ashore, but more often, the dinghy gets launched, and more robust equipment is rowed ashore.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Thanks

Hi John,

This article and the comments from Trevor and Stein really reminded me how one of the differences between the way most people sail and those who venture to tricky places like high latitudes is how much time and effort needs to go into each step of the process. This includes prepping the boat ahead of time but also can mean spending a huge amount of time just getting snugged in for the night. Where most of us cruise, I find that probably 75% of the time, we can have the anchor down and the sails furled within 10 minutes of first approaching an anchorage close enough to start picking a spot. My experience with multiple shorefasts is very limited but it is a significantly more involved process and you are not going to do it without starting the engine. It can be a lot of fun to get yourself really snugged up into a tricky spot but it can also be a real drag if you just want a few hours of peaceful sleep before continuing on.

For anyone calculating loads, I would encourage them to do a free body diagram centered around the boat as I believe that this will make the mast sense for people. In your 3 point diagram for example, you end up with 2 forces vertically on the page, the wind force and then a component of one shore tie (I am ignoring the fact that you have drawn the anchor rode as not quite perpendicular to the wind). You can then solve this for the force on the shore tie. Once that is done, you know that the horizontal component of that shore tie is equal to the anchor force. Part of the reason that I recommend it is that then the diagram also becomes fully defined. I just quickly held a protractor up to the screen (not on a computer with CAD this second) and the angles that I measured gave me a geometry that yields a load factor of 1.3 for the shorefast (I did include the non-perpendicularity) instead of 1.6 and the difference could well be that I measured the angles poorly. It is also worth noting that the anchor and shorefast loads are not equal in this scenario, the anchor has less load than the shorefast.

Eric

I defy any AAC member to find another comments section that has the word “non-perpendicularity” in a graspable context. Thanks, Eric.

Hi Eric,

Thanks very much for the fill on that, and the corrections. Good to know I was at least close, and I think close enough that the fundamental conclusions still stand?

And I agree, shorefasts are a pile of work!

Hi again Eric,

After thinking about it, rereading your comment, and looking at the diagram again, I think my mistake was to leave the wind arrow where it was in the two point diagram. Am I right in saying that to actually draw the worst case (my intention) I should have moved the wind to bisect the angle made by the anchor and shorefast? And in that case my 1.6 factor would be more accurate?

Hi John,

Yes, you are correct that with the 3 point configuration, the worst case wind angle would be different than the other 2 diagrams. And that also explains the difference in our numbers and why I didn’t have enough information to do the calculation without a protractor.

Regardless, I think that your conclusions are unchanged. This is a case of more is better if you goal is to stay put provided you get the lengths and angle about right.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Thanks again, I will fix the diagram.

I found phyllis! 3/4 to the right. Just above the bare rock spot in front of a pond. What do I win??

Great and thought provoking article.

Stay healthy and safe.

Ralph

Hi Ralph,

Well done. Hum, as to a prize, didn’t think of that! Oops.

One of our favorite anchoring tools is a laser rangefinder… there is no more guessing at distances. We know exactly how far it is to that tree over there. We have a Nikon Prostaff 550 that is maybe 5 years old. Because the display is unlighted it is only usable in daylight. That is its only fault.

Bill

Hi Bill,

That’s a great suggestion, thank you. I will add it to the chapter.

We have an old optical rangefinder that is a) also daylight-only and b) not as accurate as a laser, but has been useful at times for establishing distance off. They are sometimes seen at swap meets.