Some time ago, Eric Klem, sailor and professional engineer, asked in a comment if I had ever applied fault tolerance theory to my gear acquisition and system design decisions for Morgan’s Cloud, the aluminum expedition sailboat that has owned us for the last 25 years.

I have to admit that he caught me a bit flat-footed on that one, as I had never really thought about it…or maybe I had, but not put that name to it.

A Good Way To Think

Anyway, I read up on fault tolerance and realized that it’s a way of thinking that all of us who go to sea in small boats (or aspire to do so) should be using every day. And further, that many of my experience-based prejudices against certain systems and gear were actually the result of thinking about fault tolerance, although I had not used that label.

It Works

Also, this way of thinking, that I was unconsciously practicing, has yielded a reasonably reliable boat (touch wood) as we cruised to remote places where gear failures have much worse consequences than they do in more frequented locals where parts and services are available.

For All of Us

But fault tolerance thinking is not just for us high latitude sailors. After all, if something fails us halfway to Bermuda, we are just as much in a pickle as we would be in Greenland, perhaps more so since we can’t anchor in a nice sheltered cove to sort out the problem.

Heck, even if you do not plan to go offshore at all, gear failures are the most common cruise ruiner out there, so it still pays to apply fault tolerance thinking to your gear acquisition and installation decisions.

Defined

So what is fault tolerance? Wikipedia has this (and much else) to say:

Fault tolerance is the property that enables a system to continue operating properly in the event of the failure of (or one or more faults within) some of its components.

And I would add that it’s important to grasp that fault tolerance is different from reliability, repairability and backup (all important things to think about too).

At this point I could write a lot more words, probably really boring words, about fault tolerance theory, but let’s not do that.

Instead, let’s look at three real world system choices we sailors are faced with, and show how fault tolerance thinking makes the right choices obvious, or at least easier to arrive at. So here we go:

Looks to me that option two would be two 200ah 12v banks totalling 400ah.

That aside, good article. I’m looking forward to seeing reasons for splitting a house bank.

I have:

Start: 2 x 100ah 12v

House: 6 x 100ah 12v

Fwd: 4 x 100ah 12v (mounted at base of mast for windlass & bow thruster)

0000 cables connect all banks and all are connected with Blue Sea Systems ML-ACR & ML-RBS with remote switches at the nav station. So I can use any or all of the banks for engine or electronics.

Hi Robert,

Whoops, you are right. Option 2 consists of 4 400 ah batteries in series parallel.

Thanks for the catch, I will fix it.

Hi John,

Interesting article again, the most important part for me being the decision process in selecting critical gear. I would like to make a distinction between fault tolerant planning and back-up planning – something we gave a lot of thought to in our network business.

Fault tolerance in the network industry meant either absolute network (resiliency) or partial network (redundancy) with back-up. Most customers wanted resiliency until they saw the cost – true resiliency is very expensive and hard to implement. If the customer chose redundancy (or no fault tolerance) we would ask them for their back-up plan and where we fitted in to this. The plan needed to include full operational running of their business by alternate method ie. de-centralised computing and phones able to run without network support. Even more importantly their staff needed to be able to revert to the back-up operation without our intervention, and run independently. This needed good processes on their part, documentation and regular practises and training. For some customers this was indeed the best compromise because of their budget, location, or usage. Lesson1 – back up needs to be simple and fool-proof. This thinking can be applied to sailing but we need to understand what fault tolerance gives us, but also what it doesn’t provide. Very few systems are truly resilient, and often a well used and rehearsed back-up is much better than a partly fault tolerant option that then fails. When we are sailing, our sails are our primary propulsion system with the storm sails and working jib as back-up. The engine is secondary back-up. When we are motoring the engine is the primary, and the sails are the back-up and should be ready to hoist, halyard attached and cover off. Ditto the anchor. There is little redundancy in these systems but they are effective back-ups to each other if regularly used and practised.

Taking this further to the electronic navigation example above, option 2. This may seem to be fault tolerant, but it is important to recognise it also has a number of systemic weaknesses and dependencies. What if the GPS system fails – both units are probably using the same GPS system? What if the electronic charts are from the same provider – will the rock be missing on both sets of charts? What if we have a lightning strike – would we loose both? So for us, yes the chart plotter is now the primary system. The back-up is a well used paper chart, compass, identical route and way points with updated plot for each appropriate time interval and 2 handheld battery GPS units (and sextant in reserve). Importantly we both use the back-up system and it is part of our routine. We do have my iPad also with iSailor to give us some redundancy for the chart plotter function, and different (raster) electronic charts, but this is not our back-up. The weakness is we will only have paper passage and island group charts and we will be missing a number of the large scale island charts.

I spoke to my brother who is a Coastguard skipper about resiliency, and he says very few of their systems are duplicated and independent. Too costly and heavy and I wonder if this is true on most boats? I would much prefer a reliable primary system with a proven and well rehearsed back-up than a partial fault-tolerant system – too many “gotchas”.

Rob

Hi Rob,

Interesting, and I certainly agree that we can’t make our boats, or even a single system on them, totally fault tolerant, or even close, I also agree that other factors including backup must come into our thinking, as I said in the post.

My point was and is that we can make better decisions by thinking about fault tolerance in conjunction with other factors.

In my third example I deliberately discussed a situation in which over focus on fault tolerance would yield the wrong decision, to make just this point.

Hi John, I think your point was well made – I hope I didn’t infer otherwise. We used redundant network links often to improve availability of services to customers and this can improve things in most respects. The point I was trying to make (clumsily), is the paradoxical situation we observed with our customers where the better the fault tolerance of their system, the greater the time between failures experienced, the less likely their back-up system would work with staff able to operate it.

Rob

Hi Rob,

Now that’s really interesting about the inverse correlation between fail rates and backup effectiveness. I wonder if the voyaging equivalent might not be the number of people who think they are properly backed up because they have paper charts, but really are not because there skills are so rusty. I talked about that in the post, and I think it’s a real worry. I know that even though I navigated on paper for some 40 years—including being a race navigator, a real skill enhancer—I would fumble a lot in an emergency with all electronics down. That’s why we now have an iPad ready to go for backup.

Precisely why I bought a 2017 Almanac at the boat show. The outlay encourages sextant practice. Some may smirk, but the stars, so far, can’t be turned off. Also, if one can be said to have a navigational mind, celestial nav keeps it sharp in a way plotters do not seem to. Same with taking bearings, etc. The physical side of nav means the mental side tends (for me) to make fewer mistakes, and it’s therefore worth at least one stashed iPad to me.

Whilst I generally agree with you Marc, one of the great benefit of GPS, which many of us ornery old critters often overlook, is that it works when the sun and the stars are switched off, which they very frequently are for days on end, by clouds.

Hi Paul,

I agree. In my experience those who laud celestial navigation are often those who never had to use it with no other backup. One memory of the stomach churning anxiety of an approach to the north reef of Bermuda (then unlit) on a sketchy day old sun sight LOP and dead reconning tends make one forever grateful for GPS. https://www.morganscloud.com/2014/11/30/qa-which-sextant-to-buy-if-at-all/

Hi John,

I think there are numerous voyaging equivalents, the biggest one being the yacht itself. We put so much thought (this site is dedicated to it) to staying afloat, right side up, that most of us will never use our back up – the life-raft. But how many readers have done a sea survival course in the last three or five years and know the latest thinking on survival techniques i.e.. Plan B?

Jenny and I did our coastguard course two weeks ago. Let me add though I am not feeling smug. My three year old auto-inflate lifejacket failed to operate when I jumped in the wave pool clad in full wet weather gear, and the manual pull also failed. Luckily the back-up (he old unzip the jacket and blow air in) saved my day. We later found my gas cylinder lying on the bottom of the pool, having unscrewed itself.

Rob

Hi Rob,

I think that’s a very good tip, thanks.

Option #1 of the bettery connection diagrams is also a strictly parallel connection and will yield a total voltage of only 2 volts.

Woops again, I will fix it. Thanks

Hi All,

My, my, I was having a total brain fade the day I did the diagram and got option 1 completely wrong—I do know better…really I do!

Anyway, thanks to Gary and Tom for pointing out the error. In fact Tom was even kind enough to send me a corrected version of my own diagram—what a guy.

All of this, including a comment from Robert that picked up an error in the text, is just another reason why we value the AAC Brain Trust, as I call those of you that comment, so much.

Hi All,

I’m relatively new to this site and sailing in general and on my way to closing on our our first sailboat with a dream of one day cruising “out there”. I primarily joined this site above others as it represents true quality in dialog based on real experience. To date this is by far my favourite article since joining because it implies direct thinking to saftey, and questions I have for myself as responsible for my 7 and 10 year old, as well as my wife, and I’ll throw in the dog when we are out there. The boat we are closing is mid 80’s and has basic equipment which is what I wanted because I wanted to install a reliable system that is future proof saftey wise.

I have worked in R&D the telecommunication field for over 20 years which means fault tolerance and backup systems are at built into implicit thinking in any design. Ask yourself when was the last time you tried to make a call and the system didn’t work, and you can understand the complexity, and how it is hidden behind a simple interface of 10 digits.

In the Telecom space fault tolerance implies the system interruption, say to end users, cannot be unavailable for any period of time. One of the main fault tolerance use cases is emergency handling (I.e. 911). These systems have fault tolerance, backup systems, as well as manual systems (completely separate networks) if ever needed. Think disaster zones.

What I have gained from the above is primary system, secondary system (iPad), manual system (charts). Try to build in redundancy in all, and balance that on cost based on primary use cases (high latitudes vs lake sailing, vs coastal) against cost.

The heart of the article, to me, lies in the balance of where and in what conditions I sail in. My primary use case is safty. Achieving that allows me to enjoy sailing… 20 years of telecom and witnessing the most remote corner cases one could imagine Murphy could devise has taught me a lot.

It comes down to what level of risk you are comfortable with.

PS… sorry for posting a previously incomplete post (fat fingers on an iPad)

Hi John,

Thanks so much for the kind comment. Clearly you got exactly what I was trying to comunicate, which is huge for any writer and particularly valued by me this morning since my self esteem was in the toilet about the stupid mistake I made on the diagram.

Hello John,

The beauty, and one of the main differentiators of AAC lies in the fact that it is admiringly not perfect, but like all of us endeavours to get better and better at what it stands for. AAC doesn’t draw hostility and that’s nice, especially when a novice like me can try and add value.

You see, I would not have picked out the unintended error, and if someone hadn’t pointed it out I would not have had anything to compare it against. In other words I have learned something thru others coming together and refining a message. The internet is full of “hmmm can I trust this” questions. AAC strives to be accurate thru a living audience, that contributes.

This is huge for those of us at the starting line of sailing.

Regards,

/John C.

PS.. issued corrections have been part of print in magazines, news papers, and on-line since the dawn of each. It’s actually quite normal, and says a lot about the editor when they make them 🙂

Spirits up… you and Phyllis have created something great :).

Hi John,

Thanks again, that makes me feel better. That said I was particularly ashamed of this error since electricity is a discipline that I’m qualified and have decades of experience in. Or to put it another way, I know the difference between serial and parallel and therefore this error was the result of pure carelessness—something I have learned from.

I have a removable forestay, primarily to hank on a storm jib if necessary. If the roller furling system fails, I still have a jib.

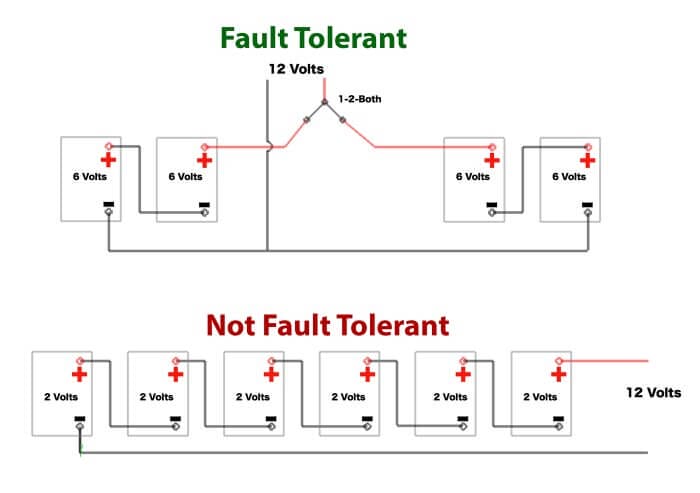

I have long followed the guidelines of Nigel Calder with respect to battery bank configurations. His thinking was that the house bank should be all in one. This is similar to option 2: two 6 V batteries in series connected in parallel with two additional 6 V batteries also connected in series. Option 2 adds the 1,2, All switch to the mix.

Here is the conundrum: the switch is now a single point failure element in the system, just like one of the two volt batteries in option 1. Granted, it is likely a high reliability item, but there are also extra wiring and connections to look after.

Fault tolerance can also be achieved, without the switch, by making sure the wiring that parallels the two 6 V series batteries can be reconnected to isolate the bad string. Not as convenient to be sure, but less wiring, fewer connections and a tad more reliability.

As you say, it is a balance.

Hi Bill,

Sure, you could do that and get the same benefits. That said, there are a lot of other benefits to the 1-2-both switch—a subject for another article—and said switch can always be bypassed if it fails.

Anyway, the key point, regardless of switch or not, is that option 2 is more fault tolerant than option 1 because a single battery failure can’t bring the whole thing down.

I appreciate the references to my well-named law–for which I have developed a corollary: If anything can go wrong, it already has–you just don’t know about it yet. And a grammatical question (perhaps for Phyllis): What is the plural of “single point of failure”?

Hi John,

After initial good design, my go-to response to reliability (or trouble-mitigating) is a suggestion that always gets raised eyebrows: “clean your boat”. I have found more problems, or potential problems, cleaning my boat than in any other endeavor. When one cleans one looks closer. And you often have the luxury of a clear and open mind (no distractions) so you can really attend to what you are looking at and notice the: loose wire, slight burn mark, bolt in the corner, etc.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

I agree, although I would add to your excellent advice: clean your boat with a very bright head lamp on.

Having a very bright head lamp is, I have found, standard operating procedure if you want to cruise with fewer issues. Because things in the brightest parts of the boat never seem to malfunction!

Hi John,

I think that you present 3 very good examples of how to use this type of thinking.

I also believe that it can be applied to more than simply gear choices but with the same caution as before. For example, I really enjoy sailing on and off our mooring/anchor and I really hate starting the engine for a short period. When doing this, I am always thinking about what would happen if the wind shifted suddenly, the steering broke, the engine wouldn’t start, the windlass jammed, the anchor wouldn’t set, I can’t find a big enough place ahead to tack etc. The key is that I can deal with any one of these faults although all together, I wouldn’t necessarily be able to. If I ever get to a point where one of these faults becomes something that I can’t manage, then I need to do something to change whether it be turn around or start the engine. Interestingly, the one that causes me to abort the most often is the concern over loss of steering in close quarters as with the sails up, this can be very hard to control very quickly.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Very good points, as always. I too plan for a steering failure in close quarters more than just about anything. It always amazes me when I see sailors hugging a lee shore to save a few tenths of a mile on their route without ever thinking about what a steering failure, or even just a broken sheet or torn sail, would result in.

I have the same sense when I see autopilots programmed to steer directly at nav aids as used as waypoints. Offing is not the opposite of awning.

John

It appears that you had vertical space under your old 8Ds and chopped out to put in the L16s

Good Idea. We lowered the bottoms of our seat lockers and now have space for 8- L16s

( P&S banks of 4 ea in series= 800 AH @ 24 V).

I have been watching since last August to see which way you jumped on Bat Type/Brand

Hi Pedr,

Yes, sorry, that article has just not got to the top of the list. Anyway, the short answer is Lifeline AGM. Proven technology that I know how to manage and get the best out of.

Hi John

A reflection on hanked on foresails. We have a demountable inner forestay which can be tensioned in two positions, outer for twin headsail rig, inner for storm jib, both hanked-on. Not a cutter rig, unfortunately. We have taken a tip from the Pardeys and have a downhaul for the hanked-on sail. With the downhaul made fast and the lee sheet taut, the sail is pretty well controlled, and a couple of nylon tapes add security. Have never used this in extreme conditions but it does reduce time and exposure on the foredeck.

Yours aye

Bill

Hi Bill,

Sounds like a good system. There’s a lot to like about hanked on sails, particularly in smaller sizes. We have a chapter on that here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2012/03/08/hank-on-sails/ and the other side of the concept here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2012/03/23/handling-roller-furling-sails/

Truly excellent article, John (and as augmented by many). I would like to see elaboration of the comment, “the better the fault tolerance of their system, the greater the time between failures experienced, the less likely their back-up system would work with staff able to operate it”. That is an immensely intriguing idea; and may not be so relevant for the relatively closed system (Morgan’s Cloud) that you and Phyllis use (and it’s only you too, for the most part).

As well, as the author of three books with a major publisher, I can tell you it’s almost impossible to proof your own work, and the more technical, the more likely this is. IOW, don’t worry about the diagram; as others have noted, this is THE major difference between the printed word and an on-line journal: every book is out of date by the time of release, and errors can never be fixed in them. Your approach here is excellent, and one of the reasons we have turned to on-line delivery of our material, by audio and video and our own forums—immediate feedback, correction where necessary, and the systems become self-refining over time. This is much more like real life! I am extremely glad I am a subscriber.

Mr. Harries,

I’ve been looking for a topic insert my questions and this one prompted it so I’ll ask it here. I’m about to splash with my completely refitted 1965/ 2018 Pearson Vanguard. I took it down to the outer hull and truly have an epoxy primed blank canvas. I built battery shelves just behind the engine bulkhead to hold two to four 6v batteries and a shelf for one starting battery near the 24hp Vetus. I can almost do without electricity (think the Pardeys on a frozen snot (grp) boat). No fridge or a/c and just foot pumps for water. I’m not quite big enough to go engineless and will have navigation lights, a few cabin lights and reading lights to back up oil lamps.

The short main question is can I have a 1/2 / both battery switch coming from the house bank to a second 1/2 / both switch from the engine? I am thinking fault tolerant so the house bank could start the engine in an emergency but remain separate otherwise. (if it’s not clear these will most likely be quality golf cart and starting lead acid)

I can and will do the actual wiring but I am having trouble with lay out for a completely new system. I have an idea of the physical equipment but could use a recommendation of someone for layout and design (diagram, shunts needed, charger location, fuses on the big stuff etc.).

I follow your thinking and get my advice from just a few trusted sources, you, RC Collins, and the like. In fact I want to thank you for the anchoring advice. I had settled on some type of spade anchor and after research and reading your articles went with an actual Spade direct from Spade (with AAC discount of course). I also had Ed Joy design the bow roller as I had none and wanted one designed right.

I will be in the water in a few weeks and will sail locally until I finish trimming the interior with just a starting battery and new wiring hanging in the mast so any direction would be appreciated.

Scott

Hi Scott,

First off, thanks for the kind words. It’s very gratifying to hear from a member that has got good value from the site. Makes it all worth while.

As to ganging the batteries. The best way to do that is to keep the start and house batteries separate, except for two connections through two continues duty relays:

This way there is no possibility of forgetting to disconnect the house and starting batteries and flattening both.

Such a down-to-earth, practical perspective; I love it. Redundancy and fault tolerant systems; this leads to being able to really relax at night! Excellent.

Hi Kit,

Thanks for the kind words.

To amplify my remarks:

These considerations are why I have two fluxgate compasses and to GPS antennas on our boat; one compass drives the AP only, and the other is used by the separate Furuno and Raymarine MFDs: the two MFDs are the redundancy (each is stand alone, with their own GPS and antenna) and the AP is a separate stand alone system to both of these. We plan using the MFDs and paper charts and follow the route using the AP manually. We do have a limited NMEA 2000 system, but it only connects the AIS-enabled Raymarine VHF and the Axiom Pro.

I will definitely add the iPad-Garmin GLO to the systems, too; excellent suggestion.

Thanks so much for this article, John. My whole focus in setting our boat for long term remote cruising had, I thought, been simplicity and reliability. However in reading your article, I suspect, subconsciously fault tolerance has been the critical goal.

I’m not good at electrics despite the best efforts of John Harries, Nigel Calder and Clark (from Emily and Clark’s Adventure on youtube), so my approach is to minimise my reliance on electrics to the basics. That means windvane steering, lots of hand pumps, lots of spare batteries for spare lights etc and no microwave, washing machine, etc. It also means I save a heap of weight by not having a genset and a heap of heavy appliances so the boat sails better.

I think we’ve been completely conned into thinking we can have everything on our boat we had in our condo. To be fair, we probably can, if we’re a marine engineer or have easy access to one or don’t mind having to constantly fix unreliable and unnecessary luxuries.

Hi Paul,

I think that’s a very good way to look at it, particularly that you are not distorting yourself to have a more technically complex boat than you are comfortable with, despite all the pressure to do so from the market and fellow cruisers.

In my experience talking to cruisers while out there, the most serene and happiest cruisers are the ones with relatively simple boats.

By the way, and to others, be very careful what you take aboard from Emily and Clark’s Adventure on you tube. A lot of it is technically sketchy, in my opinion, and worse than that, one glance at their boat tells us they are not really voyagers that actually go anywhere, but rather people that like to play with the technical-toys and make YouTube videos while going round and round an anchor. Nothing wrong with that if that’s what makes them happy, but if we actually want to go sailing and voyaging they are not the people to listen to, in my view.