In this chapter I’m going to look at some of the options that we considered to solve the dangerous problem of wave strikes while heaved-to that I described in the last chapter, and then describe what we did do.

What We Didn’t Do

But let’s start with what we didn’t do:

Running Off

I did briefly consider running off towing the Galerider drogue that we have carried for years; however, we had stopped sailing earlier because even our massive autopilot was no longer able to handle the loads and, while the autopilot might have handled steering while dragging the drogue, I had recently heard from two friends who had Galeriders pull out of a wave face, resulting in their boats rapidly accelerating—a very dangerous occurrence that, in the conditions we were experiencing, could have led to a bad broach or even a roll over, particularly if the boat was being steered by the autopilot. All in all, this option failed all five of our goals.

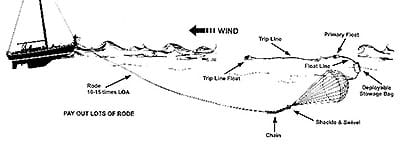

Lying to a Sea Anchor

At the time, we were carrying a 24-ft (7 m) diameter PARA-TECH sea anchor that we had bought in case we were dismasted or some other damage made it impossible to heave-to. I considered using it but was loath to do so because the deployment process required setting it on 600-ft (183 m) of 7/8″ (22 m) line as well as a trip line with three fenders on it; way more complicated and fraught with opportunities to get hurt than I was comfortable with in the very rough conditions.

I was also skeptical about our ability to retrieve this massive sea anchor and its associated gear, which would weigh several hundred pounds when wet, at the end of the blow. I know you are supposed to just pick up the trip line and pull it in, but the thought of trying to haul the boat upwind to, or motor up to, the trip buoys and snag them with a boat hook in the left-over sea after the blow, was an evolution so full of opportunities for disaster that it gave me the horrors.

We had bought the sea anchor with an awareness of the retrieval problem and were willing to accept that, since we felt that it was the best technology at the time. Assuming that it had done its job in a true survival storm, the loss of several thousand dollars worth of gear, if we had to cut it away, would be an acceptable price to pay. However, in this case, although the wave strike had been violent, we did not feel that the conditions were actually threatening our survival.

So, with the deployment challenges, together with reports that said that lying to a sea anchor in big breaking seas can result in violent yawing and pitching, this option failed two of our goals, at least.

We got rid of the sea anchor some years later and do not recommend them.

The Pardey Bridle

At the time, we were set up to use the sea anchor discussed above with the “Pardey Bridle”, a method for deploying a sea anchor while remaining heaved-to with sail up, pioneered by Lin and Larry Pardey.

I think this technique would have removed the wave strike danger without the yawing and attendant violent motion problem of the sea anchor alone. Also, if I had fully understood their method at the time, I would have bought a much smaller sea anchor than that recommended by the manufacturer and perhaps lighter gear, making deployment and retrieval easier.

Having said that, I would guess that Lin and Larry’s boat weighs less than half what Morgan’s Cloud does, making the loads a great deal smaller and deployment much easier for them.

Although we did not try it then, because of the deployment and retrieval problem, I think the “Pardey Bridle” technique, discussed in Lin and Larry’s Storm Tactics book, makes a great deal of sense.

I would also strongly recommend that anyone who goes, or is planning to go, to sea in a sailboat read the section of their book on the dangers of running off in heavy weather. I had long been uncomfortable with running off, but it was Lin and Larry’s book that really clarified and confirmed my thinking on the matter.

That said, I now believe that for most of us a Series Drogue as designed by Don Jordan, is a better option.

What We Did Do

OK, all of that covers what we didn’t do. Now let’s look at what we did do.

Having watched Morgan’s Cloud’s behaviour for a while after the wave strike, I realized that all we needed to do to solve the problem was to slow her down just a bit and keep her bow just a bit up to windward. More drastic measures like our huge sea anchor really weren’t called for.

While still heaved-to, I shackled 250 ft (76 m) of 7/8” (22 mm) nylon line to our Galerider drogue and then struggled forward dragging the substantial weight of gear behind me. After passing the bitter end through our well-rounded bow fairlead, I cleated it off and then slid the Galerider down the windward side of the hull some 10 ft (3 m) aft of the bow (I did not want the drogue blowing off to leeward where the boat could reach over it) and into the water.

This was surprisingly easy to do with the wind holding the drogue against the hull. Once the drogue was immersed, the boat slowly forereached away from it while I paid out the line. There was none of the high loads or fast run-out of the line that you get with a drogue deployment over the stern when running off.

As soon as all the line paid out, the result was immediate and miraculous. The boat slowed to a virtual standstill from the 1 to 2 knots she had been making and the bow no longer fell off to leeward when a gust hit after a lull. We lay heaved-to like this for 18 hours very comfortably with no further wave strikes.

The great thing about this drogue technique is that, unlike with sea anchors, the loads are very low. The rode was quite often slack and I would estimate the highest load as lower than what you would get on an anchor rode in a 15 knot breeze. In fact, the gear could have been much lighter than I actually used, or what would be required for a sea anchor on a boat our size. (Morgan’s Cloud displaces 26 tons.)

In the morning I was occasionally able to see the drogue in a wave face to windward. Despite it only being set on 250 ft (76 m) of line, the Galerider showed no signs of pulling out of a wave face or being tumbled. Again, I think the secret here is that the low loads on the drogue allowed it to sink well into the water thereby reducing that danger.

Originally I said that if I did it again I would use 500 ft (152 m) of line, but having thought about it some more, and in light of the above, I think I would be happy with 300 ft (91 m).

Easy Retrieval

When the wind started to ease, we easily recovered the drogue, using the anchor windlass. Even though it was still blowing near gale, I would estimate that the load on the windlass was less than that when pulling up our anchor and chain on a calm day, because the boat was still heaved-to and we were not trying to sail away from the drogue.

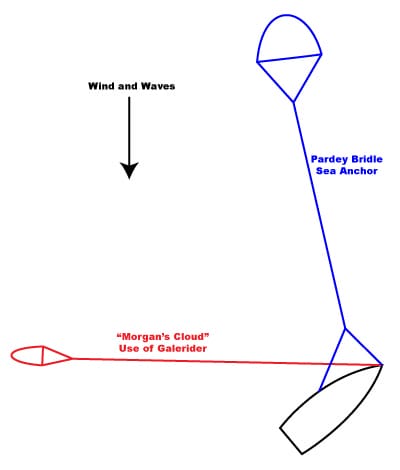

This is Different

It is important to understand that although the goal and result of this use of the Galerider are the same as Lin and Larry Pardey’s technique of setting a sea anchor on a bridle while heaved-to, the positioning and deployment of the drag device is very different. In our case the drogue ended up to windward and slightly aft of the boat with the rode making an angle of about 130 degrees to the bow and there was only one line to rig, instead of two.

Important Caveats

There are a couple of cautions with this technique:

- It specifically violates the Galerider’s instructions in which the manufacturer says that it should never be deployed from the bow of a boat.

- If the boat should tack through the eye of the wind with the Galerider deployed in this way, I think there is a chance that the boat could sail over the rode and perhaps the drogue. In a gale at sea, this could definitely ruin your whole day. However, Morgan’s Cloud showed no signs of tacking. In fact, I would be hard put to see how she could have tacked since the drag of the drogue was stopping her getting up enough speed to get her bow through the eye of the wind, nor was the drogue exerting enough pull to drag her bow through the wind—a self-limiting system. But if you have any fears that your boat might tack while set up like this, I would strongly suggest you use Lin and Larry’s technique instead.

Another Tool in The Kit

Since that day in early 2000 we have not had occasion to use this technique again, but it is really comforting to have it in our back pocket. By using the Galerider in this way, I’m confident that we can stay heaved-to safely in sustained gale force winds.

Obviously, I can’t guarantee that this technique will work for you to stop your boat fore-reaching out of her own protective slick, but the fact that just adding a little drag worked so well for us should give you a starting point to devise your own solution.

But what happens if it blows even harder and the waves get truly mountainous and breaking? What would we do if heaving-to, even with the drogue, stops working?

- Deploying a Jordan Series Drogue is now our preferred storm survival strategy.

- In the next chapter I cover some thoughts on transitioning from a being heaved-to to deploying a series drogue.

When using this technique, do you think you could transition to running off with the drogue astern without first bringing it aboard? Could you shackle a line outside the stanchions and pushpit to the rear cleats and rotate to running off by undoing the forward cleat?

Yes, I suspect you could do that. Although story after story of storm survival at sea indicates that in the vast majority of cases the set up that you go into a storm at sea with is the one you stay with. It is just too hard at the height of a full on storm to change much.

Having said that, if we were using the drogue off the bow and felt that it was becoming unsafe due to breaking waves we would, I think, cut it away and immediately deploy our Jordan Series drogue off the stern, which we keep in a bag and ready to go whenever we are at sea. I’m assuming a life threatening situation here where the loss of the Galerider would be an acceptable price to pay.

I was interested to read your ideas on heavy weather techniques. We’ve come to similar conclusions and did ride out a blow 120 nm off the SW corner of Ireland riding to our Jordan/Rimbach series drogue, which we deployed off the stern, making 40 nm downwind in 22 hrs.

How big is your Galerider? I’m going to make a small sea anchor/drogue for use when hove to and am looking for input on size. The Galerider can’t create a lot of drag, so I guess one doesn’t need a lot.

The Galerider we used off the bow, as detailed in this post, was their largest model. Having said that, I think a smaller one would have worked just fine too. The point being that with a boat that heaves-to well, like Morgan’s Cloud, it takes very little resistance to achieve the aim of stopping forereaching.

Could you have deployed a portion of your Jordan series drogue off the bow and achieved the same result as you did with your Galerider?

Interesting question. I think the answer would be yes, but without trying it I can’t be sure.

Having said that, I don’t think I would ever do that since dragging the whole JSD up forward would be a tough job in storm conditions and would leave us without our ultimate backup ready to go in case the situation got so bad that we could no longer remain hove-to.

Hi John.

Very interesting reading. Would have been good to try this out when stuck in gail south of Iceland last summer. But isn’t the setup Pardley Bridles or yours depending on how the boat is mowing while heaved to(sailing forward or drifting). Regarding the drought do you think it matters what kind is used Galerider or can it be just some sea anchor.

Hi Gudjon,

The whole idea of our system is to stop the boat sailing forward so she drifts sideways, leaves a slick, and does not get out from behind the slick’s protection. So yes, it depends on the boat and how she lies heaved-to. And that will effect the optimal size of the drogue to use. Having said that, I really don’t think the size is very critical. I like the galerider for this purpose because the webbing construction is massively strong and by letting the water through, the loads are kept very reasonable.

The one thing that I would caution against is using too big a sea anchor. It’s not necessary and the loads will get huge. By the way Lin and Larry have come to the same conclusion about size with their system.

“The whole idea of our system is to stop the boat sailing forward so she drifts sideways”

Do you think unfeathering the prop and locking the shaft might have stopped the boat sailing forward?

I wonder if keel endplate wings and/or large bulbs might inhibit the sideways drift significantly.

Hi PB,

The locked prop is an interesting idea, but I don’t think it would have stopped the bow dropping off the breeze in the lulls, which was the core of the problem.

And, yes, a keel bulb or deeper draft might have had a small effect on leeway, but then leeway was never a problem when heaved to in that boat, and isn’t generally. In fact we want the keel to be fully stalled when heaved to so that the boat will drift sideways and create the protective slick to windward. And once the keel is fully stalled things like bulbs and wings have only very small effects.

You used the Galerider in this situation. I’m assuming it was of a size rated for you vessel to be used off the stern. However, when used off the bow in this way I’d have thought it would be too large considering it was design for stern deployment and maybe risk tacking the boat, even if you did not experience this. If you had your time again would you use a down rated drouge off the bow in this way or still stick to one rated to be used off the stern for your displacement. For optimal use I doubt the same size would ideal for bow and stern. Thoughts?

Hi Tim,

Actually the Galerider we used was the recommended size for towing. But I don’t think that the size is critical for this method of deployment. As I say in the post, the system seemed to be self correcting in that as soon as the boat tried to go forward and tugged on the Galerider, she would slow down and the warp would go slack. So my thinking would be that the danger of tacking is a lot more about boat type than the size of the Galerider.

Having said all that, since I don’t much like the galerider as a stern towed device (prefer the JSD) a person could certainly go with one size smaller that recommended and still, I think, have this system work well.

Hi – im new to sailing and appreciate yoru article very much as Im learning more and more about surviving in rough weather.

However – from the sketch and article I cant quite make out exactly what you did, and if the red or blue was the way you rigged your boat.. of course its my inexperience – but i was wondering if perhaps you could re-iterate / clarify?

thanks!

Hi Francois,

The red in the diagram is how we rigged our boat. The blue is how Lin and Larry Pardey set up for heaving too with a small sea anchor. I have never tried the their way, but I think that, when done right as explained in their book, it should work at least as well as our way. Having said that, our way is easier to set up and retrieve.

John, with your method did you really sit at a total standstill? My assumption was that the key objective of the Pardey method was to create a slick that you remain firmly in and don’t fore reach out of?

Hi Tim,

Yes we did, total end of forward motion with the boat drifting sideways down wind leaving a slick to windward.

Hi John,

The Pardey Storm Tactic as detailed in their excellent book (thanks for the recommendation) has one great advantage which is the low rate of drift. The Pardey’s report a number of different sizes and shapes of vessel using their system – all experienced 1/2 knot of drift or less. With a JSD we should expect more like 2 knots.

Did you measure, or could you estimate the rate of drift you experienced in the set-up above please John? My thinking is around “what-if” we had a lee shore to consider in choosing between being hove-to with a drogue and deploying the JSD.

Many thanks,

Rob

Hi Rob,

Good point, and question, rate of drift when we are set up as detailed above is around 1 knot. One of the advantages over the JSD. The others are ease and speed of deployment and retrieval and comfort. That said, I would still want a JSD in case of getting caught out in huge breaking wave conditions.

Hi John, the extra pull of the para-anchor using a bridle would easily account for a 1/2 knot difference. Good information thanks.

Having studied “Storm Tactics”, we are electing for your approach ( + JSD) as both are largely “set and forget” strategies that are not dependent so much on how our boat behaves. The Pardey method as I read it, requires an element of adjustment for wave length conditions (to avoid surging against the para-anchor) and frequent line tending (to avoid chafe).

That said, their book is much more than a single “trick” idea, and provides excellent pointers and check-lists for preparing to weather a storm hove-to. At just $6 in Kindle e-book format it is so well worth the read.

Kind regards,

Rob

Hi Rob,

I agree, in fact I would call L&L’s book a must read at any price.

Hi John,

For bridles (and even to relieve chafe on a single line) I have contemplated attaching the bridle (or a sacrificial line) with a rolling hitch or one of its iterations. I have never seen anything written on whether rolling hitches can produce chafe and/or decrease rope strength at the knot.

I would appreciate your thoughts/experiences.

Thanks, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

Interesting question.

Although I’m a huge fan and user of the rolling hitch, I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t know answer to that. That said, my personal rule of thumb when thinking about the loads that lines with knots in them are going to take is to allow for a 50% reduction in safe working load and break strength of the original line when a knot is added.

Of course the case you postulate is more complex than that since we are interested in the strength reduction both of the line with the hitch in it, where I think 50% will be a good guess, and the line hitched to, where I don’t have a clue.

Given all that uncertainty, and the consequences of the rolling hitch being loosened by wave action, I think I would prefer a spliced bridle as Lin and Larry recommend. If I did use a rolling hitch, I would tie a double rolling hitch, very carefully, and then secure the end with a wire tie.

Stepping back a minute, the great advantage of our technique as detailed in the post above, is that no bridle is required, so everything is way simpler.

Hi Dick,

As you probably know, the Pardey’s recommend a large sheave snatch block on the end of their bridle, to reduce chafe and minimise possible weakening of the main rope as you describe. The other reason I believe, is when they let out the para-anchor rope to “freshen the nip”, the bridle is unaffected and the yacht lying hove-to remains at the same 50 degree attitude to the wind.

Rob

Hi Rob,

Yes that is a strategy, although I dislike having heavy pieces of gear “out there” on lines out of sight and bouncing around. That said, thanks for the reminder as it is always good to have alternatives in mind. Dick

Hi Dick,

I’m with you on that. I think one thing that must be bourn in mind when evaluating the Pardy bridle system is that Taliesin is quite a small boat. As boats get bigger the loads go up a lot, but of course our strength to deal with these loads stays the same. I too would worry about dealing with a block as big as required for your boat, never mind mine.

Hi Dick,

Good point, I will give that some thought. I have to say, your concern aside I like the snatch block idea as it could be more quickly deployed (and retrieved) once hove-to and after the sea anchor was in position and working as John describes. Certainly a lot easier for my money than trying to tie off a double rolling hitch on a moving foredeck with possible wave strike, and then ease both the sea anchor rode and bridle without snags – maybe I have become soft!

We plan to deploy a bridle immediately Bonnie Lass shows any tendency to round up on the sea anchor, threatening to put us about. I envisage keeping the pull on the bridle quite low, so it only loads up if the stern falls off to leeward.

I wonder if in considering this, we are forgetting that the loads involved with the sea anchor as described in John’s method above, are quite moderate compared with those on a para-anchor set-up described by the Pardeys. If so, perhaps which bridle attachment method used (block or hitch) is less of a concern either way and we could confidently use whichever best suits our purpose.

Rob

Hi Rob,

If you do decide to go with the Pardy method I would make sure that the sea anchor is not too big. I know that Larry, later in his sailing time, kept cutting the size of the sea anchor he recommended. The key point being that the primary technique in both his system and ours is being properly hove-to, not the sea anchor, which is just an addition to stop the boat from getting out from behind her slick.

Bottom line, neither we here at AAC or Larry recommend sea anchors: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/sea-anchor-system/

You probably know this, but I want to be very sure that others seeing these comments don’t get the wrong end of the stick.

Thanks for clarifying John, we are running with your tactic using this multi-purpose drogue to achieve the same result we hope: http://www.burkemarine.com.au/pages/seabrake

Using a bridle is a back-up plan, as I described above.

The Seabrake design is such that the more pressure applied to the rode, the more resistance it creates and so it should be self-regulating.

The makers claim successful multiple uses, acting as emergency steering, controlling a tow from surge, aiding active steering downwind or even providing an emergency MOB recovery harness. But what I really like is they can be deployed to dampen rolling at anchor (a common situation in the SW Pacific Islands) – so we have bought two, one for each side.

Rob

Hi Dick,

With our previous boat, we cruised with a mixed anchor rode and grappled with the same questions of attaching lines to each other. We tried 3 different techniques to ensure we wouldn’t become detached from the anchor if the line chafed through at the fairlead. One of them was to use a rolling hitch or prusik on the anchor line so that we put the load on a snubber. Our theory on doing this was that this had to fail before the main anchor rode so that we maintained our attachment. To do this, we used a 1/8″ smaller diameter line. Once properly set, we found that the rolling hitch really doesn’t move so I wasn’t worried about chafe. I think that John’s 50% knockdown figure on strength is likely right for most line constructions as the line does take on a pretty tortured path.

The whole topic of safe working loads on line is very interesting. The ABYC provides rating in their mooring load recommendations and if we were to follow those recommendations, we would have a 1-1/8″ snubber on our 36′ boat, kind of ridiculous. Their safety factor to encompass terminations, chafe, wetness, etc is on the order of 10X if you use high quality line. I prefer to take a different approach and use a 5X safety factor (3X for systems with a full backup like a snubber) and then focus on proper terminations and eliminating chafe. To eliminate chafe, I do my best to make sure that a line never moves relative to anything else it touches and use line constructions that are chafe resistant where needed. There are many accounts of broken sea anchor lines which would give me pause in doing anything to weaken the line as it suggests that we don’t fully understand the loads, the strength of the line or the degredation in line strength in this application. I have never used a sea anchor but if I carried one, I would try hard to understand these failure modes and not have them and I suspect that would mean not using a rolling hitch for a leg. In the case of a JSD, I would use the attachment as suggested by Don Jordan which does not have these shortcomings and is very similar to that tested in the MIT study.

Eric

Hi Eric,

I’m with you, no rolling hitches in a storm survival system.

Also, thanks for all the other useful information, particularly your engineer’s view of appropriate safety factors.

Hi Erik,

Thanks for the thoughtful response. Appreciated. I too, worry about losing critical lines and am moving toward having a back-up line rather than the sacrificial line I have used in the past. This back up line would be attached with the rolling hitch (doubled or I use a modified RH that has worked well for me over the years), loaded briefly to set the RH knot, and then slackened to allow the primary line to take the full load. ,The RH will only come into play if the primary chafes through and the back-up becomes necessary. Then I need to notice before the back-up goes south also.

The above may be un-necessary as my observations mirror yours: that a rolling hitch does not chafe the line it grabs onto if properly firmed up. As for line size, I like smaller line for many of these applications (especially the snubber) as long as I am around to watch for chafe and or other problems. Smaller diameter lines are just much easier to work and get tight around other lines in general and to then tease loose.

My best, Dick

Hi John,

Thanks for your thoughts. Agree that no bridle is far the best solution and your comments have shifted my thoughts on having a “sacrificial line” attached with a rolling hitch to a “back-up line” attached with a rolling hitch (or a double with a wire tie).

My best, Dick

I wondered if you might comment on towing the drogue from a midship cleat as opposed to off of the bow. I’ve got a Morgan 382, and I don’t have a lot of attachment point options. My midship cleats are very big and very strong. While it doesn’t seem like it would keep the bow from falling off, it does seem that it might keep the boat from forereaching. Thanks.

Hi Ken,

Assuming you are referring to the technique that we detail above, I think it might work, but there is no way to know for sure other than trying it offshore in gale force conditions. That said, I’m really surprised that the boat does not have decent cleats forward and if it were me I would be focusing on fixing that anyway because there are so many situations in cruising where strong belay points are vital, both forward and aft.

Thanks, John. I have the standard cleats that came with the boat. I re-read the article a few times, and it seems that I didn’t process your discussion regarding the loads created by the drogue while hove to. It sounds like my cleats should be up to the task. I’ve not experienced gale force conditions offshore as of yet, so I was trying to ascertain the best method for my boat. Thanks for the quick response!

I’m wondering if it would be feasible to deploy a ‘mini jordan’ drogue (which has the added benifit that I can make it myself) rather than the Galerider for this purpose? Perhaps a line with 10-15 cones on it with a suitably long line (for my 5000kg boat)? Include a light chain on the end (5kg’s?) might be the business.

Hi Ian,

I really don’t know. The problem with these things is that there is no way to know for sure, other than trying it in extreme conditions, so if it were me I would stick with the Galerider because we know it works. The other advantage of the having a Galerider is it makes a great emergency steering device, again this has been tested.

One thing, I’m not sure that weighting any sort of drogue off the bow when being used as described in the post above, would be a good idea. I fear it might sink down so far during lulls that when the boat tried to accelerate in a puff the restraining load would not have an optimal vector.

Not saying that would happen, just that it’s a worry and just one of the many possible unintended consequences of going with an untried option.

Hi John,

From your reply comments above to Ian, do I understand correctly that when deploying the Galerider drogue as described, you are NOT using any weight attached to the drogue?

Hi Jim,

As I said above, no weight and I don’t recommend it. This works in a completely different way than a JSD so we should not confuse the requirements of one with the other.

I have a question on heaving to. You eluded to it a little in the chapter about using an engine. My boat is tough to heave to. Easily rounds up and tacks. So i figured that using the autopilot (ap) to keep the boat pointed in the right direction might help to prevent tacking? Would that work? And if so, should the ap be in heading hold or wind mode (maintain wind angle)? What do you lot think?

Hi Rob,

Good question, but no having the autopilot on won’t help when heaving to, or at least if it does you are not heaved to. The point being that when heaved to correctly the boat is making little or no forward way, so steering has no effect.

If your boat is tacking, that means that she is not heaved to properly, so more experimenting with sail combinations is in order. We have a chapter on that here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/how-to-heave-to-in-a-sailboat/

My guess would be that setting up with a storm staysail may help, and having an inner forestay is a good idea anyway.

If you have any further questions as you solve this I’m happy to help in the comments to that chapter.

Hi Rob and John and all,

It is my take that learning how to heave-to is hard in light to moderate winds: the forces just need to be potent to figure out sail/traveler/rudder combinations that get things just right. In light to moderate winds everything just felt to me sloppy and the boat never really “settled”. My most successful attempts were in off-shore gale force winds where I just went out to practice. I learned a lot, but I did not have to contend with big waves and swells. My handful of hove-to attempts in modest winds when waiting a few hours for dawn to go into an anchorage were fine, but again felt sloppy and I have been fortunate to have not needed to employ what I had learned in a storm at sea.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Ps. In talking with others, I think the most neglected tool in heaving-to is adjusting the traveler.

Hi Rob,

We hove to and fore-reach a lot. A few observations:

As John says, if the autopilot would work then you aren’t hove to, which is where your foils have stalled (no flow over keel or rudder) and you are slowly drifting to leeward in your own “slick” with your bow up into the waves, as if magically parked behind your own portable ocean reef. Few modern beamy yachts will do this in gale conditions without the assistance that John describes in his excellent post above.

Interesting too that Dick’s yacht is more flighty in light conditions, but settles in heavy airs. Ours is the opposite, where as the wind increases, we just can’t reduce sail enough to slow down enough whilst remaining hove to AND we can’t hold the bow close enough to the wind to avoid the odd wave slamming into the hull, as we continually sail out of any slick.

Our experiment streaming our sea anchor worked a treat, but took some setup and retrieval that doesn’t suit quick or casual use, which is where heaving to is so useful (like making dinner in wild conditions, dealing with an issue aboard, or waiting an hour for a daylight port entry).

So your idea of using the autopilot may have merit if the objective is fore-reaching, not heaving to. This is an “active” survival tactic that suits fully crewed, modern fast racer cruisers, where the waves are too big to hove to, or there are chaotic wave patterns, and / or a lee shore to prevent running off.

This was all described in dramatic detail after the 1999 Sydney Hobart storm event in this excellent book:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/843276.Fatal_Storm

by Rob Mundle.

I was meant to be part of the crew on the record setting and winning entry Nokia that year, though ill health forced me into a passive spectator role, so this read was particularly compelling. A number of yachts were lost and many lessons learned – it was our antipodean “Fastnet Race storm”.

With fore-reaching you are heavily reefed under storm sails, and with the issue you describe, possibly with the jib backed to prevent tacking if you can maintain enough headway over and through the waves. You are taking the waves at a narrower angle on the bow than when traditionally hove to.

About 1.5 to 2.5 knots is good we find, with backed jib.

Normally in these conditions you would be hand steering around the biggest waves, probably with engine assist. Certainly the full Sydney Hobart race crews were all hand steering. But if your yacht was settled in this attitude, then perhaps the autopilot could take on the hard work on WIND VANE mode. But someone would need to be in the cockpit on watch, ready to take over the helm instantly.

I find practising in daylight around any decent headland with a strong wind against tide situation works well in simulating gnarly offshore conditions, although with a much shortened wave period.

And I would be interested in John’s and other’s thoughts and experience with this.

Hi Rob,

Fore-reaching is a big subject and more than I can tackle in a comment. That said, I should do a chapter on it since it was the way I got through my only full on survival storm, and also how we got through several gales back in the day.

Spoiler alert: I don’t recommend it as a survival strategy for short handed crews.

Hi John, that would be a very interesting read – look forward to it.

Full agreement on the short-handed part, but if you have to preserve sea room, then having a fore-reaching mode could be life preserving, short-handed or not.