-

Support Steve at SV Panope

30 CommentsReading Time: 2 minutesFreeRead more: Support Steve at SV PanopeLet’s support a guy who is making a real difference.

-

Goodbye “Morgan’s Cloud”, What a Ride

63 CommentsReading Time: 3 minutesFreeRead more: Goodbye “Morgan’s Cloud”, What a RideThe sale of our beloved “Morgan’s Cloud”, a custom aluminum McCurdy and Rhodes expedition sailboat, closed yesterday.

-

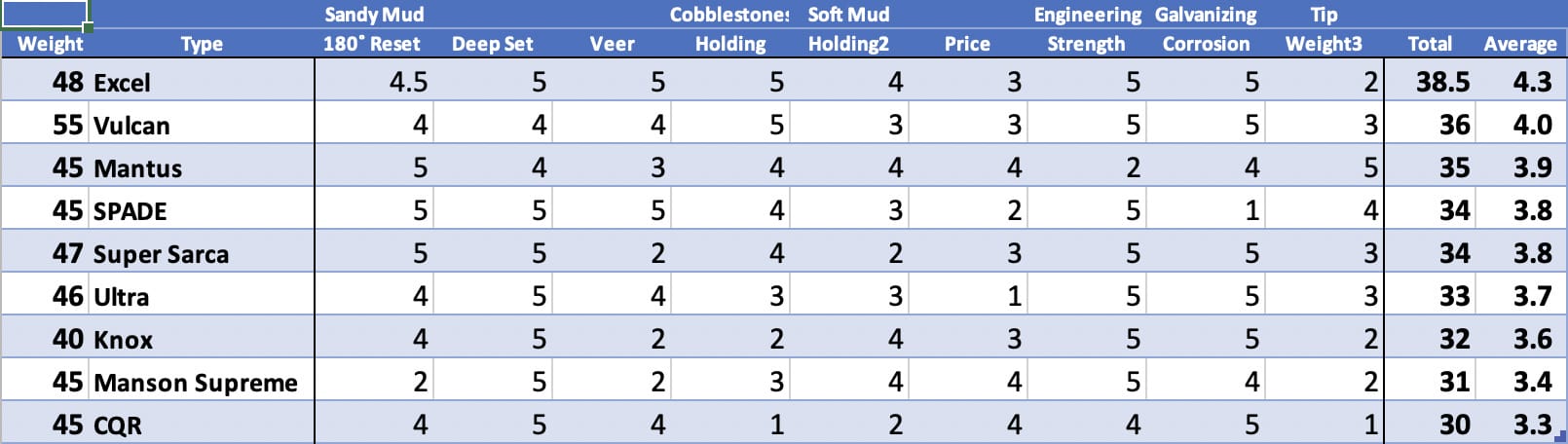

Making Anchor Tests More Meaningful

125 CommentsReading Time: 10 minutesMembersRead more: Making Anchor Tests More MeaningfulJohn starts with testing from “SV Panope”, adds a large dollop of experience, and comes up with his own best anchor table as well as demonstrating how you can do the same.

-

Colin & Louise are Buying a New Sailboat

44 CommentsReading Time: 8 minutesFreeRead more: Colin & Louise are Buying a New SailboatWe can all learn a huge amount when two of the most experienced sailboat owners anywhere go boat shopping.

-

Choosing A Cruising Boat—Shade and Ventilation

18 CommentsReading Time: 12 minutesMembersRead more: Choosing A Cruising Boat—Shade and VentilationA cruising boat without adequate shade and ventilation can make life a living hell once we head for the palm trees. Here’s how to choose a cruising boat that will be comfortable in hot places.

-

Refits, What You Need to Know

17 CommentsReading Time: 2 minutesFreeRead more: Refits, What You Need to KnowNew boats are horribly expensive, so most of us will be faced with refitting an older boat to get out there. We have recently reorganized all of our many articles on how to do just that.

-

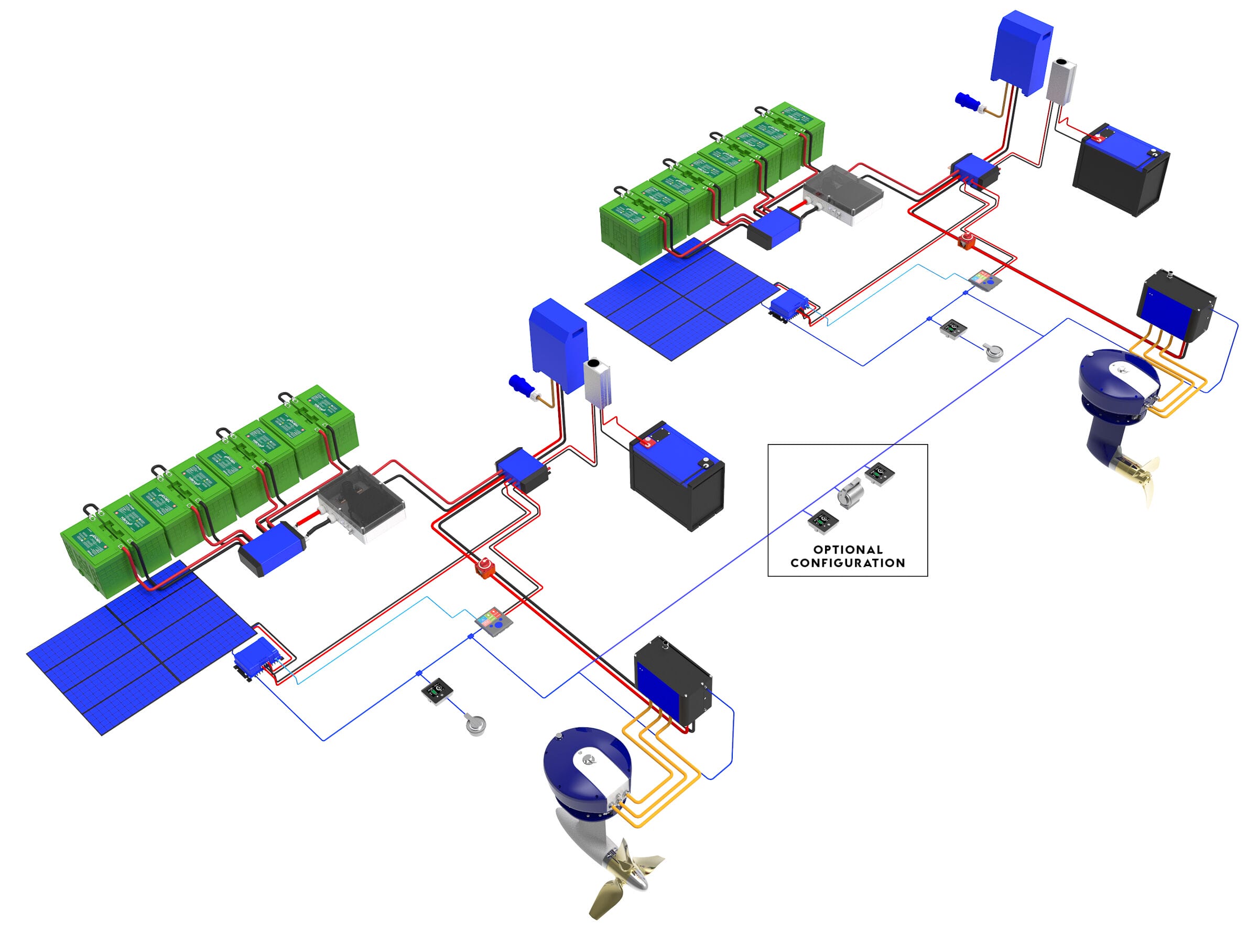

When Electric Drive Works For a Cruising Sailboat

148 CommentsReading Time: 11 minutesMembersRead more: When Electric Drive Works For a Cruising SailboatLessons we can learn from Jimmy Cornell’s Elcano Challenge when considering electric drive for a cruising sailboat.

-

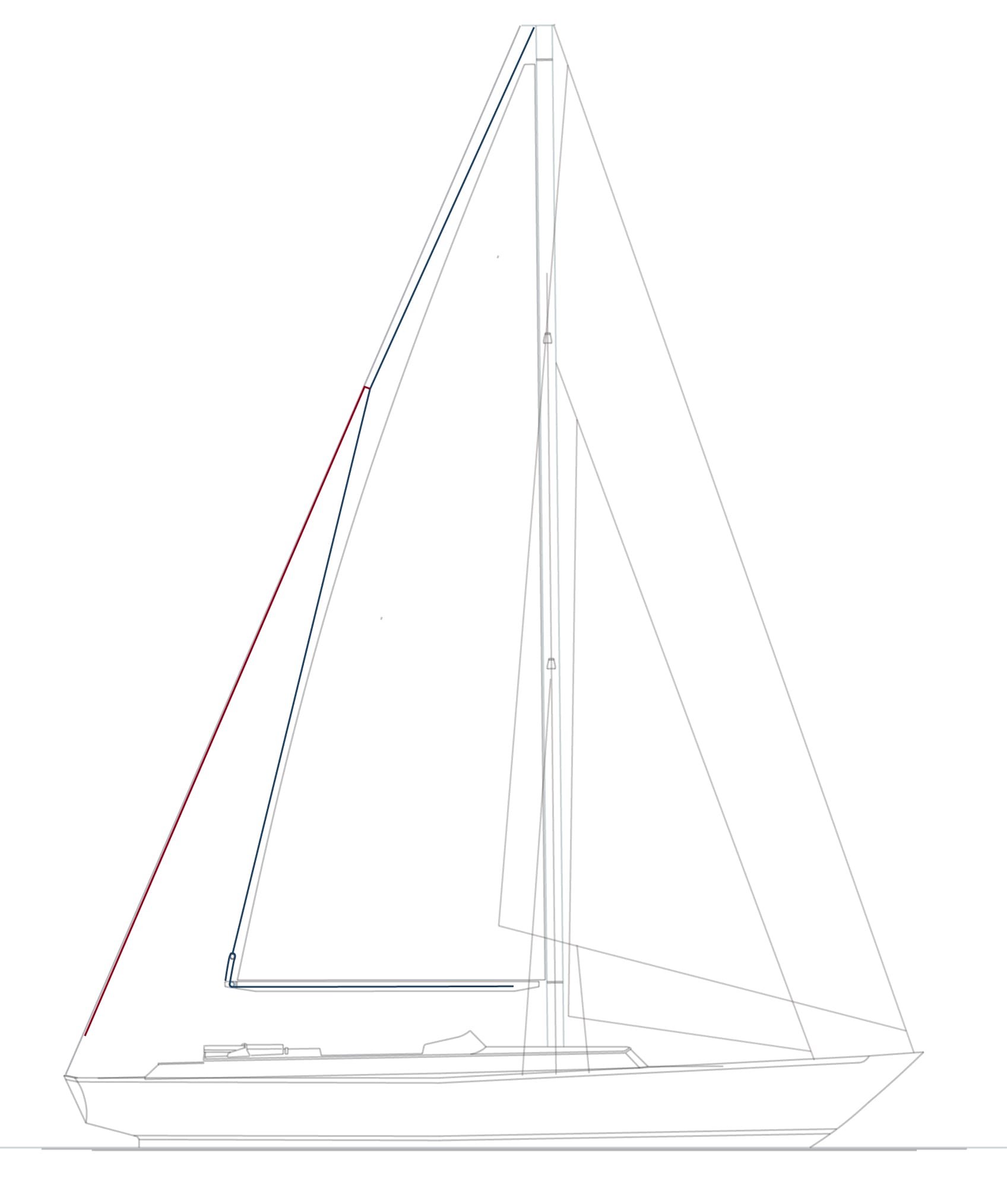

Roller Furling Headsail Risks and Rewards

45 CommentsReading Time: 6 minutesMembersRead more: Roller Furling Headsail Risks and RewardsAn interesting question from a member gets John thinking about how to handle headsail roller furling failures, and risk versus reward on a general basis.

-

Choosing a Cruising Boat—Shelter

30 CommentsReading Time: 11 minutesMembersRead more: Choosing a Cruising Boat—ShelterJohn takes a deep dive into the tradeoffs between open cockpits, dodgers, enclosures, raised salons and wheelhouses on offshore boats.

-

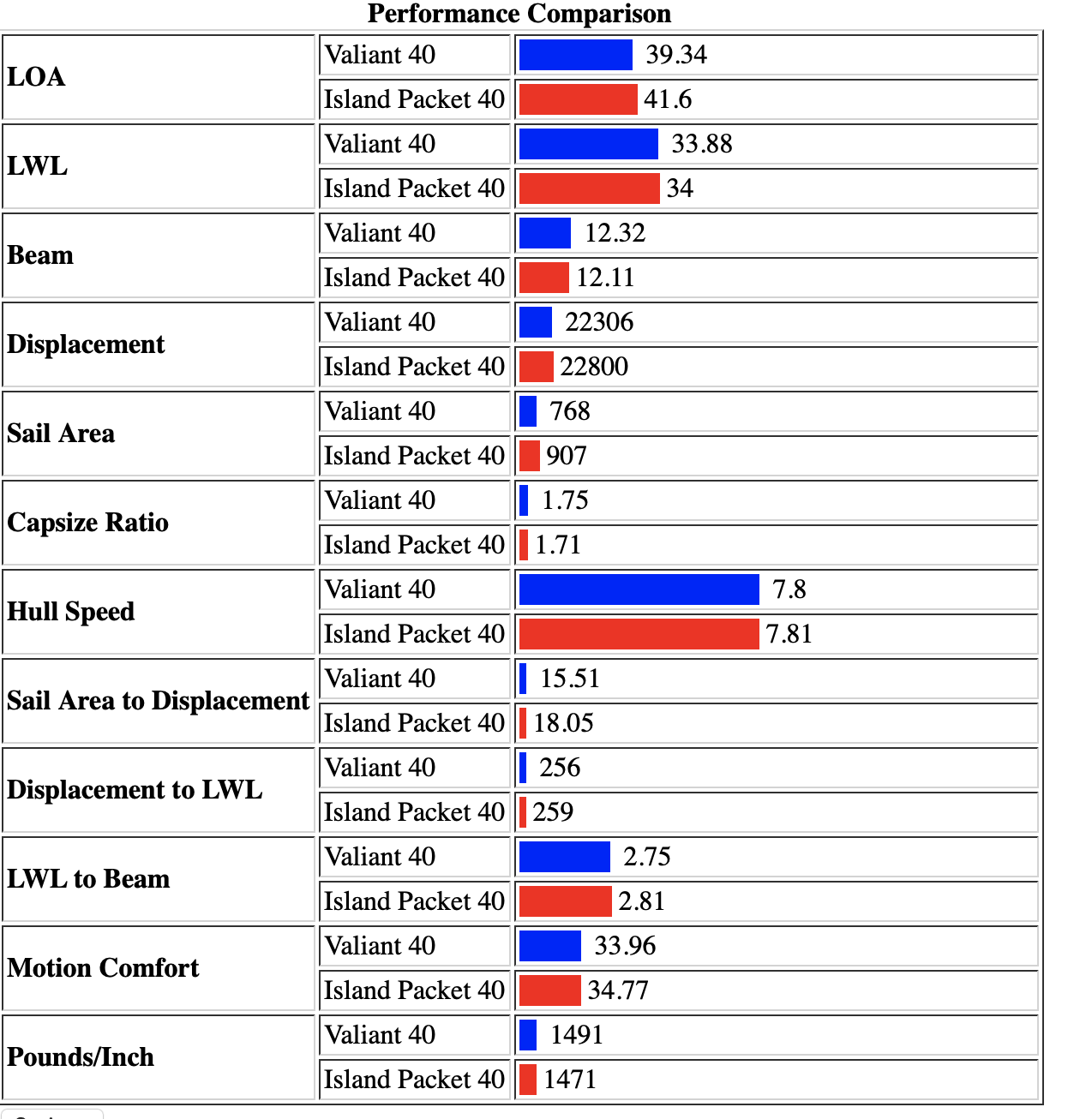

Q&A—Sailboat Performance, When The Numbers Fail

18 CommentsReading Time: 3 minutesMembersRead more: Q&A—Sailboat Performance, When The Numbers FailA member asks an interesting question about why a boat that appears slower from the numbers is actually faster.

-

Offshore Sailboat Winches, Selection and Positioning

57 CommentsReading Time: 10 minutesMembersRead more: Offshore Sailboat Winches, Selection and PositioningThese days the offshore sailing community seems to be fixated on rig automation, but a well-specified and installed set of winches will contribute far more to a successful passage than all that expensive failure-prone stuff.

-

Best Offshore Boat Cockpit Cushions

40 CommentsReading Time: 4 minutesMembersRead more: Best Offshore Boat Cockpit CushionsGood cockpit cushions are a lot more important on an offshore boat than you might think.

-

A Day on a Great Canal

12 CommentsReading Time: 8 minutesFreeRead more: A Day on a Great CanalTransiting the Welland Canal in a sailboat makes for a long day, and half the night, of line handling and ship avoiding.

-

Buying a Boat—A Different Way To Think About Price

81 CommentsReading Time: 5 minutesMembersRead more: Buying a Boat—A Different Way To Think About PricePhyllis and I have been thinking and talking a lot about which boat we will buy after Morgan’s Cloud sells. And a big part of that has been setting a specification and budget, but in a different way.

-

Safety: We Can’t Do Or Even Learn About It All

37 CommentsReading Time: 6 minutesMembersRead more: Safety: We Can’t Do Or Even Learn About It AllThese days it seems like hardly a month goes by without the announcement of a new and/or improved safety device, aggressively marketed as the latest thing that we all must buy, to the point that it’s getting impossible to keep up. Here is how John decides which of these new technologies to put energy into understanding and which to ignore.

-

Cockpits—Part 2, Visibility and Ergonomics

49 CommentsReading Time: 8 minutesMembersRead more: Cockpits—Part 2, Visibility and ErgonomicsThere are few areas on any boat that are used for more diverse tasks than an offshore sailboat cockpit. Everything from lounging on a quiet day at anchor to handling a fast-moving emergency at sea with a bunch of sail up…in the black dark…in fog…with a ship bearing down on us. Given that, picking a boat with a good cockpit layout is one of the most important parts of boat selection. Let’s look at what really matters.

-

Cooking Options For Live-aboard Voyagers—Part 2, Liquid Fuel

62 CommentsReading Time: 7 minutesMembersRead more: Cooking Options For Live-aboard Voyagers—Part 2, Liquid FuelIn Part 1 I looked at induction electric cooking and concluded that for most cruiser usage profiles, particularly for us live-to-eat types, propane was still a better solution, and greener, too. So what about liquid fuels Alcohol, Kerosene and Diesel? Let’s take a look.

-

Companionway Washboard Hacks And Getting Out There

50 CommentsReading Time: 5 minutesFreeRead more: Companionway Washboard Hacks And Getting Out ThereMost sailboats have companionway washboards sliding into channels. And while this is a good simple solution, a little work needs to be done to make them really safe. Here’s a simple hack that will take less than half an hour and cost less than US$20, together with a couple of tips on how to actually get out there, rather than working on your boat the whole time.

-

Cooking Options For Live-aboard Voyagers—Part 1, Electric

49 CommentsReading Time: 8 minutesMembersRead more: Cooking Options For Live-aboard Voyagers—Part 1, ElectricThree months ago I did some experimenting with induction cooking and wrote about it. And that spawned four more articles as I investigated the changes to a cruising boat’s electrical system required to support high loads like those from electric cooking. So now we can properly answer the original question, is electric cooking practical on a yacht?

-

Cockpits—Part 1, Safe and Seamanlike

76 CommentsReading Time: 11 minutesMembersRead more: Cockpits—Part 1, Safe and SeamanlikeThese days there seems to be an endless fascination with yacht (both motor and sail) cockpit amenities, but we must never lose sight of a cockpit’s primary function: to be the command and control centre of a vehicle that operates in a potentially hostile environment.

-

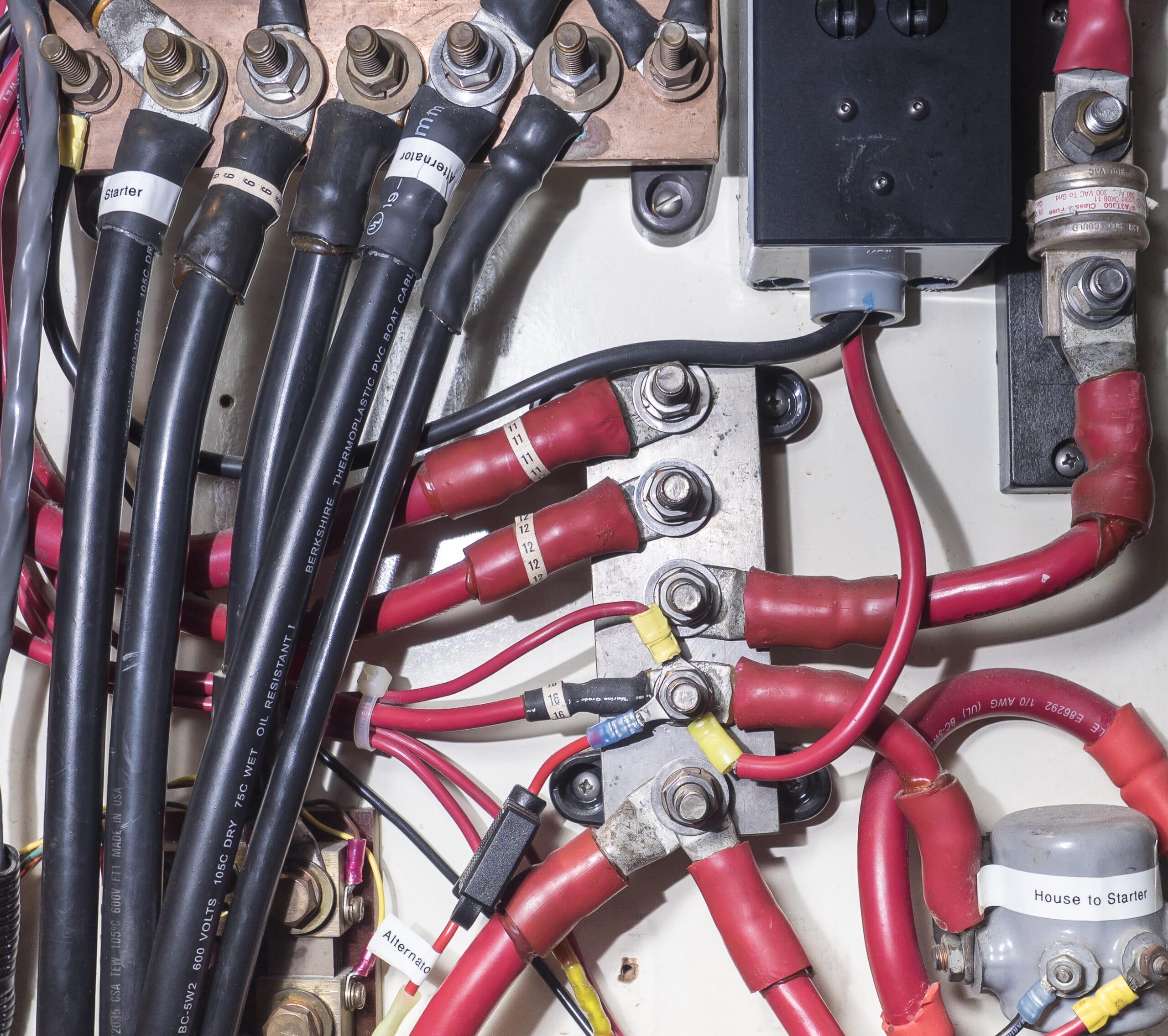

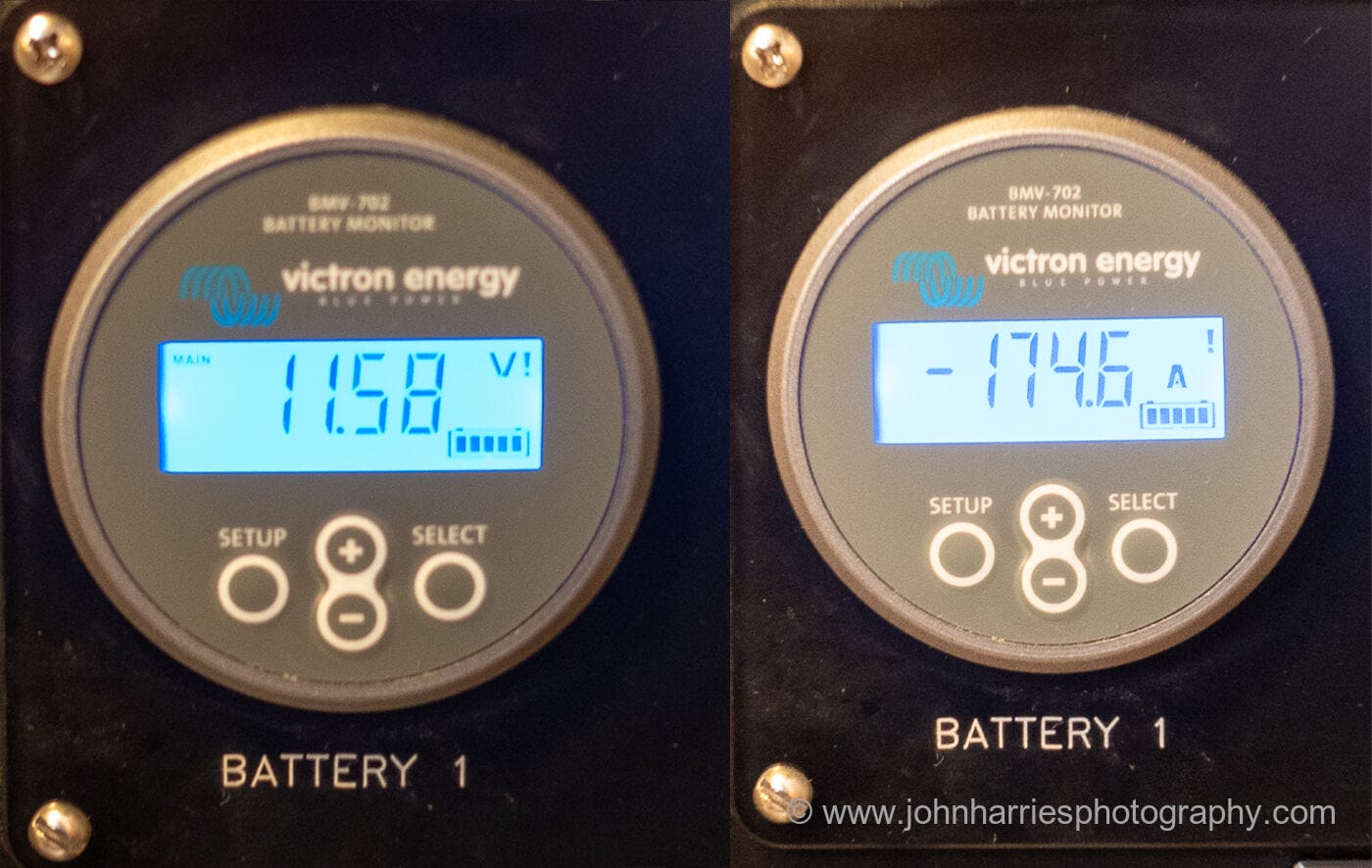

Should Your Boat’s DC Electrical System Be 12 or 24 Volt?—Part 2

67 CommentsReading Time: 7 minutesMembersRead more: Should Your Boat’s DC Electrical System Be 12 or 24 Volt?—Part 2In Part 1 we learned that it was inefficient, and often impossible, as well as potentially dangerous, to supply the high-load equipment, that so many cruisers seem to want, with a 12-volt system. And, further, that the solution to this problem is either to forgo all very high-current (amperage) gear, or select a boat with a 24-volt system. So let’s look at that.

-

Should Your Boat’s DC Electrical System Be 12 or 24 Volt?—Part 1

81 CommentsReading Time: 7 minutesMembersRead more: Should Your Boat’s DC Electrical System Be 12 or 24 Volt?—Part 1So which is better, 12 or 24-volt DC systems for live-aboard cruising? Like most things, it depends. Here’s a definitive way to determine which is best for your boat and usage.

-

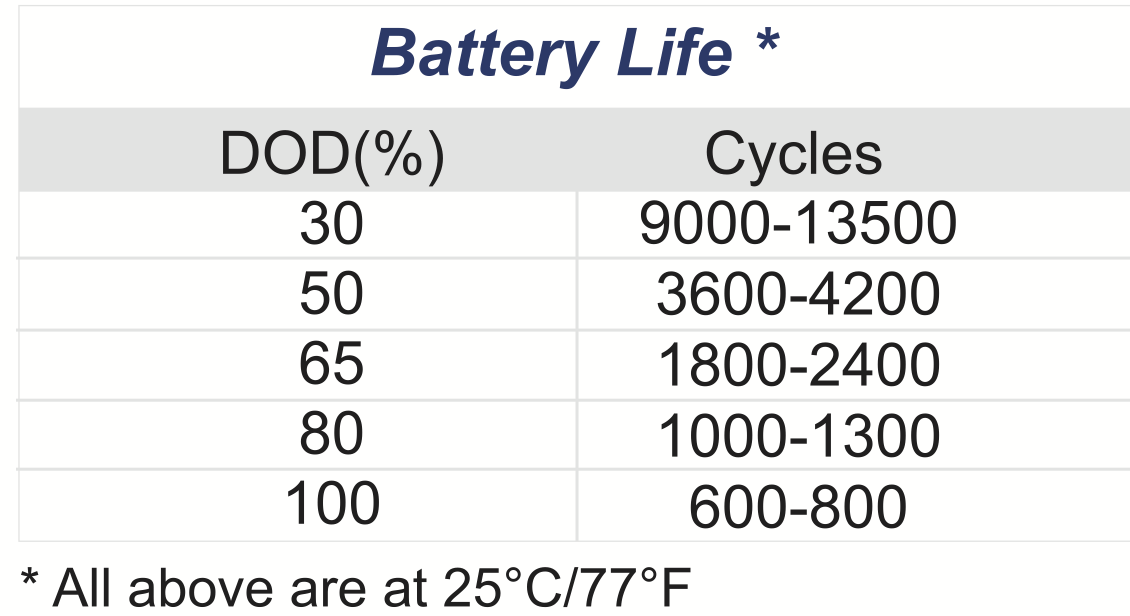

Firefly Carbon Foam Batteries Are Great, But Read The Fine Print

41 CommentsReading Time: 4 minutesFreeRead more: Firefly Carbon Foam Batteries Are Great, But Read The Fine PrintThese days we are seeing some great new battery technologies for a live-aboard voyaging boat, but with that we are also seeing some wild claims. It’s important not to let our enthusiasm for the former blind us to the latter.

-

Topping Lift Tips and a Hack

66 CommentsReading Time: 5 minutesMembersRead more: Topping Lift Tips and a HackDo you need a topping lift? John shares how to decide, and how to rig it if so, as well as a cool hack to reduce topping lift related chafe and noise at sea.

-

The Danger of Voltage Drops From High Current (Amp) Loads

63 CommentsReading Time: 6 minutesMembersRead more: The Danger of Voltage Drops From High Current (Amp) LoadsThese days we are seeing more and more gear added to boats, much of it AC supplied through inverters from the battery, that demands current (amperage) way higher than even dreamed of a decade ago. But will our electrical system buckle under the load? Here’s how to figure that out ahead of time.