The six-foot waves are beginning to pile up and the wind, a gusty Force 4, is backing just enough to call an end to wing-on-wing. Maverick V is in her element, loafing along at a happy seven knots under full main and #3 jib, as we come up to a beam reach and start scanning the horizon for the markers that’ll guide us back into the commercial shipping lane we’ve been carefully avoiding all day.

She’s picked up some weather helm and the Hydrovane is asking us to take in a reef on the main, but in a few minutes we’re going to be meeting 700-foot freighters in a 600-foot channel, so it seems wiser to take the canvas down and let the Yanmar stretch its legs. We’ve covered 46 miles in eight hours—not bad, for a day that started out dead calm. Tomorrow’s adventure is something totally different. We’re going to cover just 23 miles, horizontally, but also 99.5 metres vertically.

Yes, it’s time to go gunwale-to-gunwale with thirty-thousand-ton commercial traffic, and transit one of the world’s great canals.

Experiencing History

Maverick V, Seaway Welland. Check-in confirmed, I see your fees cleared on Secunik, please be ready at the staging dock at 0700 and call us on VHF 14. Transit should take about eight hours.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

This is not the first Welland Canal, nor the second, nor the third. Today’s iteration is the fourth, in service since 1932, and under construction—punctuated by war, epidemic, market collapse, and just about every other kind of crisis—for 19 years prior.

Every great canal, worldwide, shares a similarly colourful history. They are, almost by definition, among the grandest works of civil engineering that humankind can produce. Monumental in scale, in schedule, and in budget, the great canals—the Panama, the Suez, the Welland, the China Grand, the Kiel, the St. Lawrence, the Erie, and the list goes on—testify to the victory of blood, sweat, ingenuity, and the almighty dollar over the tremendous natural power of geology and hydrology.

Every cruiser ought, at some point in their sailing career, to see one of these creations firsthand. Not from the drive-in shoreside viewing platforms, or from Google Earth, but the way they were meant to be experienced: from the deck of a ship in transit.

An Exercise In Patience

NACC Capri, Seaway Welland. Proceed under Bridge 21 to Lock 8. Maverick V, hold position at the staging dock, we’ll try to get you in at 1100.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

We paid $200 for our transit; the 5200-ton cement carrier would have paid closer to $4,000 and is on a schedule.

It’s just as well. In a perfect example of “Location, Location, Location,” the first business we encountered after tying up at the pier was a Chinese restaurant that happily stuffed us to bursting (with plenty left over) for a modest fee.

Sixteen hours later, we’re still feeling a little lethargic, and using what energy we can muster to fix up a few issues from yesterday’s shakedown run.

I flip through the canal’s procedures and regulations manual, a 59-page tome in which valuable tidbits about how the lock staff will handle your lines are interspersed with dry technical regulations about the calibration of the ship’s Draught Information System console.

It’s nowhere near as captivating as an AAC article, but I’d hate to be the yachtie who pisses off a Vessel Traffic Services officer in the 13th hour of his 9-hour shift over some dumb procedural mistake.

Maverick V, Seaway Welland. You’re next after Baie Comeau, sorry for the delay, please be ready to clear Bridge 21 at 13:00.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

Lock 8 is a control lock, guarding the canal from Lake Erie’s seiches: the wind-driven pseudo-tides that shift the shallow basin’s water east or west, causing as much as a twelve-foot swing in water level at the far ends of the lake.

Today, its drop is just a few feet, and we slowly rotate the boat in place to keep her clear of the lock walls until the lower gates open. The Azimut 50 motoryacht behind us issues bow and stern blasts from its thruster packs. Nobody bothers with lines at Lock 8.

COLREGS? Yeah, about that….

The canal here is 160 metres wide, and with our nearly shoal-draft keel, we could go within a boat length of the bank if needed. Traffic is light, though, so as long as we stay to the right of anything coming upbound, we’re good. The Azimut plows ahead, a few knots faster than us, trimmed seven degrees up with a wake to match.

There’s a strict no-anchoring, no-mooring rule along here, with one exception: a damaged ship needs to get the hell out of the active waterway, like, ASAP. We pass the Alanis, stacked high with wind turbine tower segments, a large gash across her starboard bow.

Not long after, the coal bulker Florence Spirit comes into view, her hull split wide open with the fresh imprint of the Alanis‘s bulbous bow. While I have not yet seen the official report on the accident, video taken from the shore shows the coal bulker cutting across the path of the Alanis, her steering gear apparently having jammed to port, then being rammed a few seconds before she would have hit the bank.

I double-check our own steering. The freshly replaced main cable is still taut, and the boat responds nicely to a manual touch on the vane’s independent tiller.

The smashed-up ship is a sobering reminder that we yachties are only visitors here, this canal is the freighters’ turf and they are unforgiving of mistakes and failures.

We glide in toward Bridge 11 to find the Azimut circling impatiently. VTC is only willing to raise the bridge once for both yachts. Serves him right for speeding on ahead.

The bridge goes up, and we carry on. While the Seaway is now heavily automated via a central command office, I can’t help but double-check that the bridge is indeed up and locked. Back in 2001, a bridge attendant, badly hungover from the previous night’s antics, lowered this exact bridge on top of the MS Windoc, somehow without killing anyone in the process.

The Flight

It’s rare to cover much more than about 15 vertical metres in a single lock. The structural engineering gets ugly and the ship handling gets awkward. Larger drops, like the Thorold Flight that’s about to lower us over the Niagara Escarpment, are done by chaining lock chambers end-to-end.

Coming down Lock 7 is easy. Two friendly attendants toss us some huge coils of surprisingly light three-strand mooring line. Line handling, while downbound, is dominated by one overwhelmingly, critically important rule: You never, ever, tie off that line to anything, ever.

Single-handing is, of course, out of the question, but a double-handed cruising boat rarely needs to take on any extra crew for a downbound transit. With one person on the bow and one on the stern, each paying out the line by hand and fending off with a boat hook, lowering is a calm, almost peaceful operation.

For us, used to looping our own ropes around the permanently-affixed drop lines of the Rideau locks, this vastly larger chamber is only a minor change in procedure, and the sheer amount of open space to play with (5400 square metres) is a refreshing change from the densely-packed recreational traffic of our older, smaller local canal.

An upbound boat faces more of a challenge. While the downbound lock is tranquil, the upbound one is turbulent with white water rushing in. Few (if any) canals will allow upbound passage with fewer than three crew, and four or more are generally recommended. The two biggest, burliest crew will haul in the lines, while the others lean on boat hooks wedged against the lock wall.

If you’re big enough, far bigger than any yacht an AAC reader might own, you might not bother with lines at all. The Maccoa, squeezing into Lock 7 with little room to spare, and coming to a dead stop within a couple of metres of the intended position, is grabbed by the robotic hands-free vacuum moorings as a few of her crew lean on the rails, looking rather bored.

Baie Comeau, Seaway Welland. I’m sorry, I can’t get Bridge 5 out of your way yet. Just hang out in Lock 4, the technician’s on his way.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

The freighters aren’t moving. A bridge is jammed halfway open, and the local hydraulics expert is flying back down Highway 406 in an old minivan stuffed with spare parts. A ship arrestor is acting up, too. It’s not clear whether the huge hydraulic arm has failed to deploy the thick ship-catching cable across the front of the lock, or if it’s unable to retract it, but either way, that lock ain’t moving.

We loiter for a while as the bridge is fixed and the freighter backlog cleared, then carry on down the flight: locks 6, 5, 4 in quick succession. “Yeah, that’s typical Seaway”, says one of the line handlers.

Despite dire warnings of “holes the size of Volkswagens in the lock walls” and “inch-thick rebar sticking out everywhere”, we find our fender board to be nearly unscuffed. Sailor gossip does, indeed, become somewhat exaggerated over the course of two or three days.

The Black Gates of Mordor

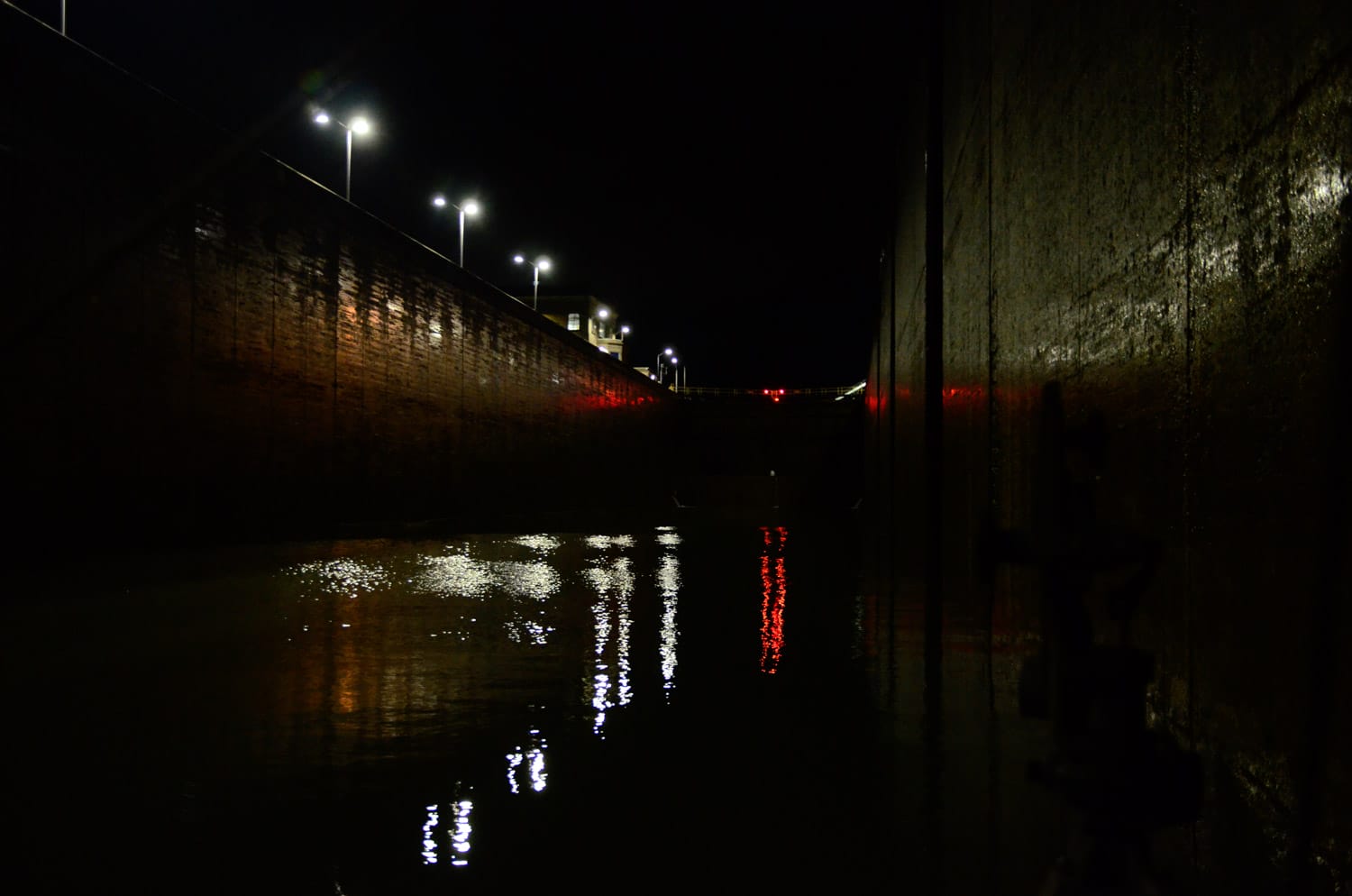

The downstream gates begin to crack open, and for a moment, I’m braced to repel a rampaging horde of Uruk-hai. The armies of Sauron do not materialize, but the view over the Niagara Escarpment does. It’s a thoroughly unnatural, thoroughly engineered environment, and you can feel the absence of normality. While aboard a sailboat, one should not look down a hundred-metre cliff to a horizon five times farther away than it ought to be. Yet here we are.

Just wait there above the lock, please. The yachts are in the lock, they’re stuck a metre down, something broke. The technician’s on his way.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

We’re dropping very slowly, just a few inches per minute. A 600-volt hydraulic pump has tripped a thermal overload, and with a quarter-megawatt arc flash hazard in its control cabinet, nobody’s willing to go check and reset the thing until a high-voltage electrician shows up to lock it out with the proper safety gear. Our line handlers’ shift has ended, and we’re trading idle banter with the yacht behind us and with the bored-looking guys on the pier.

Maverick V, Seaway Welland. Watch for a red bulker upbound one mile ahead of you, please keep to the east bank under Bridge 4A.

Seaway Welland vessel traffic control

It’s long past sunset. The freighter, unladen and riding high, is twice as long as the channel is wide. We see her range lights, showing us head-on right down the middle. We pass, port to port, so close that we can see the welds between her hull plates. She carries on silently to the south, as we continue northbound to the final locks.

Clearing Out

The Seaway can’t sleep until all ships are clear and safe. A small yacht like us will certainly not be allowed to remain within the canal, as long as it’s physically possible to get us out. Midnight comes and goes. We catch another set of lock lines. The water slowly drains away. A kaleidoscope of coloured light plays off the wet concrete walls as sodium lamps, mercury lamps, LED lamps, and signalling lamps compete for dominance.

The great black gates open for the final time, revealing a rolling swell funnelled in from Lake Ontario. Twenty hours into our eight-hour transit, we are free. We find the upbound staging dock and, with no objections from VTC, tie up for bed. The great canal adventure is at an end.

Well told, and very reminscient of how we spent our own summer locking down the St. Lawrence. Did you happen to notice at the top lock how wonderfully the AIS targets appeared at unprecedented distances? Because even in Toronto Harbour, I could see vessels locking up the Canal until they vanished over the top.

Our only complaint about the process was the tendency of the lock operators to put the “morning” and “evening” pleasure craft transits, the ones pre-booked, at the full mercy of the commercial traffic, meaning we had the “morning” slot not lock through until as late as 4 PM, which necessitated a rush to the next lock or marina before sunset as we didn’t care to be in the Seaway in some places after dark.

We found all the commercial vessels professional and safe (unlike some of the recreational yahoos) and we would, as depths permitted, go a little out of the channel to allow them to pass if they were crossing a similarly large vessel. Even the ones passing up at 12 knots or so threw less violent wakes than a few of the power boats passing too close on some summer weekends, but then a lot of the Seaway in Quebec is also clearly “cottage country”.

I generally like being around commercial vessels, in this area. They’re predictable and they follow the COLREGS precisely. On the other hand, I was once asked if I could design a sound-homing torpedo specifically tuned to target a two-stroke SeaDoo.

I share your complaint, Marc, about being scheduled at the mercy of commercial traffic. The Welland Canal operators specifically declare predefined time slots for small-craft transit; they should either respect those (rather than shifting them back by two hours at a time until a gap presents itself), or openly admit that it’s “first come first serve” with no guarantee that a transit will be allowed at that time.

We don’t carry AIS, at least not yet. Maverick V came to us without modern electronics, and we navigated our delivery passage by paper chart and hand-bearing compass, with smartphone GPS serving as a cross-check. She’ll be getting her electronics fit-out over the next couple of years.

We have found AIS very useful in the Seaway and as an adjunct to radar in foggy or night conditions, or, as we learned, in crowded ports such as Halifax with long and sometimes constrained approaches.

Parts of the Seaway are both narrow and, outside of the channel, surprisingly shallow, and often we would “see” an overtaking cargo vessel on AIS some time before it would appear aft or foward of us “around the bend”. This gave us time to investigate the depth contours in front of us, which was helpful in terms of knowing if we could go where they could not, drawing about 1/4 their draft. Is it essential? Not if you keep a proper watch. Is is a useful tech that ties into complementary tech, such as VHF and radar? We have found it to be so.

Hi Matt,

Nice story told in a nice way. It reminds me of some experiences from European inland waterways. The strangest lock I’ve done was on the Rhein – Main – Donau Channel on the newest highest part, finished in the mid 90ies, linking the Black Sea / Mediterranean and the North Sea. Several of those locks have been blasted into the bedrock and have massive elevation. The one I’m thinking of was entered through a hole in the rock wall, through a short tunnel entering the chamber through heavy rain from the walls. Looking up to the small piece of sky between dark 26 meter (85 feet) high walls with water dripping off them on all sides was very strange, like in a science fiction movie. When the heavy steel gate lowered behind us it even felt creepy. Since the locks are modern with floating bollards, it was an easy process, though.

On European inland waterways it’s strictly forbidden to go fast and make a big wake. Doing either will invoke a big fine, so it’s fairly unusual. However, in more open waters, some motor boaters have a low awareness about wake issues. A few times I’ve been able to elevate their awareness by means of a simple water hose. If I spot one looking like he’s planning to pass by at an inappropriate distance and speed, I have pointed the hose across his course and started spraying seawater, reaching about 20 meters (65 feet), while looking intently at the skipper. Apparently that makes the coin drop. They have invariably slowed down and increased distance. To that reaction I have given a polite bow and a friendly smile with thumbs up.

Motor boaters are simple beings. They learn best from clear imagery and a simple disadvantage / reward logic. Some of them can achieve a surprisingly high level comprehension, almost like a good dog. 😀

Thanks for the water hose tip, Stein!

BTW, fun fact about Rhein-Main-Danube Channel: the basin between the locks of Hilpoltstein and Bachhausen is the highest point on Earth reachable by a seagoing vessel. Anyone who transits the channel gets automatic bragging rights.

The water hose is a nice touch, Stein, I’ll have to remember that one….

There is a large gap in boating education surrounding powerboat speed, wake, and etiquette. An understanding of these things is conspicuously absent from most books and curricula. As a result, a lot of powerboaters seem to think that going faster always burns more fuel, so they slow down to 10-15 knots. What they don’t realize is that with almost all planing hulls, there’s a band of extreme inefficiency at those bow-high plowing speeds, and fuel consumption per mile will decrease significantly if they either slow down enough to drop the bow, or speed up enough to lift the stern and level out. I don’t mind being passed by a 40-footer doing 25-30 knots; up there, its wake has flattened out and I just have to ride over two or three gentle rollers. Being near the same 40-footer at 10-15 knots, where it’s throwing up a huge breaking crest, is a much less pleasant experience.

Exactly…and Stein, I appreciate both your dry wit and your wet hose method.

Thanks Matt I enjoyed this narrative very much. And it prompted me to go and read up more on the Welland and it’s history. It’s a part of the world I doubt I will ever get to, but I feel like I’ve experienced a sliver of it through your eyes all the same.

I’m glad you enjoyed the read, Philip. None of us can ever explore all the places we dream of seeing, but it’s always fun to share a bit of it this way when the chance permits.

Thanks Matt. Now I know what happened that night in 2001 when we were held up in the canal for hours. We were told eventually that the gates had closed on a freighter’s bridge wings “because of the newly-installed computer system”.

Your account brought back vivid memories of “a night to remember”!

Yes, there was a bit of “what do we blame?” going on after that particular bridge vs. ship incident. The official report, though, made it pretty clear – while they couldn’t determine how much alcohol and Darvon-N were affecting the bridge operator, he was definitely impaired enough to drop the bridge on top of the ship that was right under him. Seaway management took a lot of blame for not having any protocols or safeguards in place to prevent something like that. It’s a pretty useful case study in several ways, and really drives home the reason why we always save our beer for the pier.

That’s a standing order on our boat, and given that even small cruisers can weigh several tons, I am always a little surprised when I see drinking underway. Tied off, it’s a different story, but I stop at one even in a dead calm anchorage…the forces at play demand full sobriety. Besides, when you are transiting things like rivers and canals during Canadian summers, you are usually too tired to stay up much past sunset.