While thinking about how to make the Adventure 40 an incredibly trouble free and reliable ocean voyaging boat, I have worried most about two areas: chain plates and the rudder.

Both for the same reason: they are the area in conventional fiberglass production boat construction where stainless steel and fiberglass come together in the presence of salt water to make an unhappy marriage.

Let’s leave the rudder aside for this post.

Stainless steel chain plates, particularly if they are set inboard and poke up through a slot cut in the deck, will, if the boat is sailed hard offshore, eventually leak, usually within a few years of launching, sometimes much sooner.

And once water gets in, the chain plate itself starts to corrode—a problem that is serious enough that any boat so built that is more than ten years old should have its chain plates carefully checked, and after 20 years replacement is often the only safe alternative.

Yes, I know, there are a lot of different ways to try and leak-proof a stainless chain plate. Some of them even work for a while. But the facts are that as long as you are mixing two different materials with radically different mechanical properties and trying to keep water from getting between them, things are probably not going to go well in the long term. Something to remember when refitting a boat—teak decks, or any wood trim for that matter, come to mind.

One of the very cool things about metal boats is that the chain plates are made of the same material as the hull and are bonded to it by welding, thereby avoiding leaks and other problems for many decades.

I want to do the same sort of thing with the Adventure 40, and Matt Marsh, engineer and all around smart guy, with a lot of hands on experience with fiberglass, makes a very convincing case that we can do just that by making the chain plates part of the hull.

One option would be to build the composite chain plates outside of the boat from pre-preg materials over a mold and then bond the resulting assembly to the hull and/or bulkheads, as well as the deck, with epoxy or Plexus adhesive.

I’m pretty sure this would work well since a friend of mine made a lot of complex fittings, including a goose neck, in this way, very quickly and inexpensively.

And I have another friend, one of the world’s most experienced composite boat builders, who assembles the high tech boats he builds with Plexus and says that the resulting bonds are stronger than the laminated assemblies they connect.

By the way, I’m not the only one who does not like stainless steel chain plates. The new Navy 44s have composite chain plates because of the intractable leaks that the older generation of boats suffered from.

A Campaign Against Stainless Steel?

And if you are beginning to think that I have a “tude” (Bermudian dialect for attitude) against stainless steel, you would be right. I think that we yachties put far too much trust in the material and often use it, just because it looks shiny and strong, when other materials like good quality bronze, galvanized steel, aluminum, or composites would be better and more reliable.

Comments

If you have solid engineering knowledge or first hand experience that will help us solve this problem in a cost effective way, both for the Adventure 40 and chain plate replacement in older boats, please leave a comment.

How about titanium?

Hi Steve,

No, not the answer for two reasons: very expensive and still a very different material with very different properties from the hull and deck.

If we just wanted to change to a better metal, then good quality bronze would probably be the first choice.

But as long as you are mixing fiberglass and metals you will never get a good watertight bond between the two.

The whole idea here is to fabricate the chain plate from a material that will expand, contract and flex in the same way as the hull and deck and that can be reliably bonded to them.

Hi John,

Bond pre-molded fiberglass/carbon chainplates into the boat with a secondary bond using Plexius or epoxy? Not on my boat! Look at a finite element analysis of the proper fiber orientation for load distribution and you will see why.

Plexus certainly has its place, and one of those is bonding an internal liner into a hull where the large surface area and imprecise fit makes use of the tenacious and somewhat flexible adhesive properties.

I’m no fan of stainless steel either— I’d always prefer silicon bronze for things like bobstay tangs that regularly get dunked in salt water.

Hi Richard,

I never said carbon. As I understand it, it is usually better not to mix carbon and lower modulus fibers in the same fabrication.

Having said that, I’m talking at least 200% of what I know here.

Fact is that good composite chain plates have already been done on a bunch of boats, including the new Navy 44s, so it must be doable.

The bigger question is, is it doable at a price we can afford and with consistent QC?

Failing that, I’m with you in looking at bronze over stainless steel.

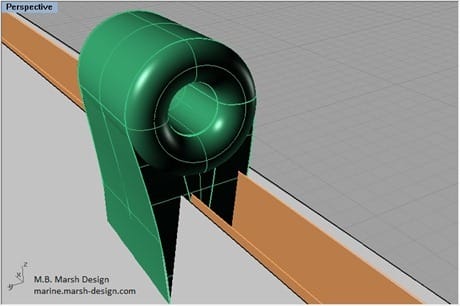

Richard, while I agree with you that gluing a composite plate into the hull with Plexus is not the way to go, I respectfully disagree with your negative assessment of composite chainplates in general. We are talking here about long loops of continuous fibres, moulded right into the part they connect to; this is a tested and proven system that is well understood. Glued-on plates of flat stock are a very different animal and one that I do not recommend.

I have built similar components in both carbon and e-glass, by hand with minimal or no tooling, that took no longer to make than their metal equivalents would have. There are many well-documented successful examples of composite chainplates that are fully integrated into the hull.

Knowing how the fibres have to be oriented is one key to making it work; creating easy-to-use tooling is the other. The former is a solved problem, the latter can be a bit tricky to engineer but is certainly doable.

Hi Matt:

Actually I have a very positive attitude toward composite chainplates and would use them on any custom boat I was building for myself. My reservations are for a production run of perhaps 100 boats where the goal is to deliver function and reliability at a price point no other manufacturer currently meets. The valid comparison is not the time it takes to build a one-off item in composite vs. metal, but the difference in time and expense of building upwards of 1,000 semi-one-off fabricated items vs. calling up your favorite CNC equipped machine shop and having them delivered to the factory door.

John, I’d change your comment that metal chainplates always eventually leak to “improperly designed chainplates that protrude through fiberglass decks are a frequent cause of leakage. ” We could make the statement that all aluminum boats in salt water eventually disintegrate and be perfectly correct as well! (LOL) Time and the sea always win in the end.

A properly designed metal chainplate tang installed as D. Stevenson described in an earlier posting should easily outlast several sets of standing rigging, and need never leak if re-sealed when the standing rigging is replaced every ten or 12 years.

Six or eight years ago, Richard, I would have agreed with you 100%- doing this in composites, in production, would have been a royal headache of the worst kind.

In that time, though, composites manufacturing technology has been flying ahead at a crazy pace. In this case, you’d drape a handful of fibres through a set of CNC-milled moulds, clip that to the gunwale of the hull mould (or to the edge of a bulkhead that’s being infused as a flat plate on the floor), feather out the fibres, tape the mould seams, bag the rest like you normally would, and hook up a vacuum hose.

I wouldn’t have even considered doing this on a production basis without the incredibly precise tooling that modern CNC provides, or the excellent infusion resins that are now available, but it’s not nearly as difficult as it used to be.

Regarding leaks: I’m inclined to attribute the “leaking through-deck chainplates”) problem to structures that aren’t nearly stiff enough and to a generally poor understanding of how to properly seal complex joints.

Kurt Hughes recently sorta/kinda discussed this very thing on his blog and suggested a strong, leak-proof, inexpensive, and easily done on a production basis method…

Welcome here, Boat Bits (For those who don’t know him, RLW writes a fun and interesting blog, click on his initials.)

Thanks for the link. Makes a really good point that carbon is not required and that E-glass is many times stronger than required once you make it thick enough to look strong.

Have we considered bonding a pair of composite load-distributing loops to the hull and passing SS bolts through the loops to be the sacrificial (maintenance) wear and shroud attachment point? An arrangement such as this seems like it would give the best of both worlds. Making and bonding loops should be pretty easy even in an assembly-line type mass production setting.

Hi Charles,

If I understand you correctly, that is just what most composite chain plates look like. So, yes.

That’s essentially how they work, yes. Loops of continuous fibres form a thick, strong bundle with an eye above the deck, and the tails of those fibres then fan out into the hull or bulkhead. You then use a metal bolt or toggle through the loop to attach the rigging. This bolt (unlike the bolts that secure a traditional metal chainplate) is not subject to anaerobic / crevice conditions that would cause corrosion.

Why aren’t we looking at the stick. Maybe a redesign here and we can forget about the chain plates ?

Hi Myles,

We have talked about free standing masts a lot in the comments to previous posts in this series. I think that while they do have advantages, they are not the way to go for the Adventure 40. However, if, once you have read the debate on the subject to date, you have something new to add, I’m all ears. Please append your comments to those on the same subject in previous posts.

Great idea. A stayless Adventure 40 with carbon fibre mast ought to be an option.

I would not even consider using stain-less steel of any stripe for replacement chain plates when suitable titanium alloys are readily available in flat bar. Expensive? Depends on your frame of reference doesn’t it? How expensive do you imagine it could be to lose your rig in the middle of a passage?

Hi Gary,

Good point. If I were faced with replacing stainless steal chain plates, I would certainly look at Titanium, although I would have to do more research and talk to a metals expert, since I’m not well informed on the properties of the metal. I would also look at good quality bronze.

However, my preferred alternative would always be a composite solution, where practical, for the reasons I state in the post.

It seems a key focus of this thread is how to avoid deck leaks in the long term.

We can easily avoid crevice corrosion by using bronze or another metal, but the potential for deck leaks would remain.

It may be useful to set a reference point against which we can compare – may I ask what is the “best practice” method we can use to install conventional metal chainplates in order to minimize leaks?

I assume it is to build a hard doughnut around the chainplate exit point, and fill this in with very low modulus butyl.

But if I am assuming wrong, can John or Matt or Richard correct me? It will be useful to have that reference point.

Hi Martin,

The best answer that I have heard to the problem of stopping leaks around stainless steel chain plates is that used and detailed by very experienced Valiant 42 owner Dick Stevenson, which is basically just as you suggest.

Hi John,

I’ve looked for Dick’s ideas on chain plates, but no luck. Can you refer me to the article where they appear?

Thanks,

Tom Bohanon

Hi Tom,

Sorry, despite 15 minutes of using our advanced search I was not able to find that comment either. Dick keeps a fairly close eye on the comments, so maybe he will come up again on that.

On my old Fastnet 45 I solved the problem once and for all by making some two part teak blocks that fitted around the chain plate tightly at the top and had a slight hollow in the base around the plate which I filled with boat life and then screwed them down to the deck while the goop squished out.

I think Dick’s method was very like that, although I suspect he used butyl rubber as I know he is a big fan.

Thanks John. I’ve seen some descriptions of using SS or aluminum cover plates in a similar fashion to your use of the teak blocks, but it seems like better odds of stopping a leak with yours. I’ll lurk around to see if Dick chimes in…he’s got a lot of good ideas.

Hi Tom,

Yes, a lot of ways to do this, but the key point, I think, is that the goop needs to be compressed from the top, not just slathered around the sided of the chain plate.

Way back in 1989, I installed some ‘hybrid’ chainplates on a series of 64 foot John Shuttleworth charter cats. For the main chainplates, John designed massive CNC-cut stainless plates, with broad horizontal slots below the usual holes for clevis-pins. The plates were installed through the glassfibre deck (solid at this point) and were a tight fit in their slots, so the deck played its part in stabilising the plates against rocking. We ran UD carbon through the slots and down onto the bulkhead or web below, in the obvious fan pattern, and that was that. 12 tons of cat with enormous righting-moment and as far as I know they are all still out there.

However, I still don’t have any problem with properly-installed stainless chainplates: totally agree about butyl bedding and also the use of good wide cover-plates, thick enough to be fixed down without bending, so as to compress the bedding nicely but gently.

Last thought: make sure the chainplate is thick enough to fill up the space between the toggle legs: there’s nothing nastier than a thin chainplate!

I recommend that you focus on a cost effective solution. Exotic and non-proven solutions means increased production cost.

Stainless steel chain plates are a proven method, and very cost effective. If installed properly they will not leak.

If you still have concerns about leaks you should perhaps focus on accessibility in case it leaks. If the chain plate is easy to access a leak is not the end of the world. Easy accessibility normally means less installation time in production.

Hi Roland,

I couldn’t agree with you more about focusing on proven solutions. However, where we differ is in classifying composite chain plates as exotic and unproven. Five years ago I might have agreed, but not today.

Also, rest assured that we won’t do something that will increase production costs unless, and this is an important point, it reduces 10 year cost of ownership and the frustration of STDW (stuff that doesn’t work.)

And yes a chain plate leak is not a world ender, but trust me, it’s damned unpleasant, particularly if it’s above your own bunk!

Hi All,

Several people have opined in these comments that I have overblown the problem of leaks around metal chain plates that poke through the deck of a fiberglass boat. I think I know why that is:

One of the non-intuitive things that I have learned over my 40 years of going offshore on sailboats is that what works for years on a boat sailed inshore can fail in a matter of months on a boat sailed consistently in ocean swell.

I’m not really sure why that is, but I suspect that it has to do with the frequency and amplitude of cycle loading from ocean swell when compared against inshore chop.

The result is that a boat that is perfectly watertight through her hull ports and chain plates for years when racing and cruising inshore starts leaking like a sieve as soon as she is faced with a few months of ocean sailing, and often a week will do it.

This is not idle speculation but based on hard experience delivering and racing fiberglass sailboats to and from Bermuda to the US east coast.

I envision the Adventure 40 as a boat that will be able to sail around the world (say 30,000 miles) without significant problems, and certainly without the chain plates leaking.

And then, six months after getting home from her first circumnavigation, do it again in an equal trouble free way.

And that goal will, I believe, only be served by designing a system that does not rely on trying to waterproof the joint between two materials with radically different coefficients of expansion, and stiffness, and one of which is very difficult to adhere anything to.

Hmm. The most common thing to leak on a boat is portholes, skylights and

genoa tracks.

Hi Roland,

A very good point. But in both those cases the leaks are from poor construction techniques, not fundamental to the nature of the materials and their use, as I believe is the case with metal chain plates poking up through a hole cut in a fiberglass deck.

John,

I thought that I would throw out an idea, I am not sure that I have sold myself on it but something to ponder. Certainly, composite chainplates would be the best but it would be an idea if you had to go metal.

My first thought was, is it really a problem? My conclusion is just like yours that it really is. The next thought was, can you mitigate the effects through good interior design but I don’t think that would work terribly well as you still have fresh and salt water entering through the deck. Finally, I thought about whether you could make it easily serviceable so that the people who actually sail offshore could reseal them easily once a year but again, I don’t think that this is the solution.

This got me to thinking about how we would have approached this problem when I worked as an engineer for large industrial air compressors and steam expanders. These machines are full of critical seals both from a safety and longevity standpoint and we had extremely few problems. The major difference in application was that in those machines, you could very tightly clamp two rigid surfaces together so that an o-ring or gasket (some of these are pretty advanced these days) would work. So why couldn’t you do the same thing on a deck? The problem with current designs is that they have too much relative movement between parts so we try to deal with this through using flexible goop which invariably looses its seal with one surface. There is no reason why you couldn’t design a chainplate with virtually no movement relative to the deck.

What I have in mind is a chainplate which sits flat to the deck and bolts through the deck to a massive backing plate. Both plates need to be designed to be rigid enough which should be easy and the deck needs to be designed to take a pretty high compressive load. The bolts would be torqued up pretty hard so that even at maximum rigging tension, the friction force of the plates to the deck prevent any movement. A little deflection and tolerance stackup is acceptable with a properly sized o-ring, this is standard stuff that any good mechanical engineer should be able to put numbers on.

From a production point of view, this would be doable at a reasonable cost. You could cast your chainplate and backing plate (including attachments to whatever internal structure are required) and do a bit of post machining to get the flatness tolerances. O-ring grooves are expensive on high run items as they take a little while machining but are probably cheap compared to many other options being discussed. The trick with the deck would be that you would need to get it flat and it could not be too far out of parallel.

Sealing head bolts have been around for quite a long time and they really work well. The simplest ones use an o-ring under the head and need to be torqued down hard enough so that there will be no relative movement between the head and the plate it contacts. Using these bolts in conjunction with an o-ring outside of all the bolt holes between the chainplate and deck would fully seal everything.

The biggest problem that jumps out at me is that you have created a really rigid point in the deck so you need to transition to the rest of the deck which is less rigid. I have also not run any numbers of the compressive strength of a solid fiberglass laminate versus the necessary bolt preload.

As I said at the beginning, I am not sold on this and have not done any real engineering on it but it might work. Thoughts?

Eric

Hi Eric,

A very interesting idea and just the sort of out-of-the-box thinking I hoped this post would spur.

You do a much better job than I have of identifying and explaining why flat bar chain plates poking up through the deck will always tend to leak, thank you.

I don’t have enough engineering knowledge to really comment intelligently, although I thought that castings where not very reliable under high loads, but I may be wrong about that?

Richard (RDE) does make some good points about the potential problems with this type of assembly, although he only dealt with welded fabrications (undesirable) and machined from a solid block (expensive).

I guess the key question is would this idea actually be less expensive and easier to do than composite chain plates, particularly when you take into account the deck laminate requirements? I’m guessing not, but that is just a guess.

Anyway, thanks very much for the very well reasoned comment.

John,

I see that you feel composite chainplates will work which is great.

I did want to respond to the question about cast parts under high loads. Cast parts have gotten a bad reputation due to poor design and manufacturing over the years. Nowadays, there are 3D computer modeling tools which can be used to ensure that the mold fills and cools properly. Most problems are related to voids and areas where the metal cools too quickly and isn’t bonded to the surrounding metal.

From an engineering perspective, the first thing is to design a part which is compatible with casting (basically the part shape determines this). Then you need to do stress analysis on the part. When determining your allowable stress, it is standard to use knock down factors for castings as they are not as strong as billet material. In the end, you have to have a slightly larger cast part provided that your design and process control are good.

Spartan Marine Hardware casts all of their bronze chainplates. I am not aware of any failures and they have a lot of sea miles on them so it can be done.

I hope that this answers your question.

Eric

Hi Eric,

That’s a great explanation, which taught me a lot, thank you.

Sounds like it could be a viable alternative if composite chain plates don’t workout for us when we actually come to try to make them.

I have always had great respect for Spartan, so that is useful too.

High Eric,

This is exactly the type of chainplates which are fitted on my Nicholson 31, except without the o ring. I believe they are the originals ( built 1977 ) and I have just inspected them with the intention of replacing with nitronic 50 or silicon bronze. There is no evidence of leaking (even after all this time) so it would appear this is a well engineered design and a good alternative to composite.

Magnus

Hi Eric,

What you describe here is basically what my own boat has.

The original rig was masthead, inline spreaders, deck-stepped. In the early 1980s the previous owner decided he wanted a bit more juice, so in went a fractional, swept spreader, keel-stepped rig from the next-bigger model boat from the same designer — all done with his approval.

Anyway, as you can imagine this necessitated new chainplates in new positions. The above deck part is just a flat plate with an upstand with the appropriate holes for the rigging, and is connected to the backing plate by six bolts. The backing plate is a litte different in that it’s actually a small “I” beam with end plates, and it spans the gap between the bulkhead and some very substantial FG knees that were added. But the above and through deck concept is as you describe, and it is a success.

In the 40 years since this work was done, the boat has done at least 30,000 miles — many of them offshore — and no leaks.

Eric,

You are absolutely right. It is all about preventing the movement between deck and the chainplate. This is a technique used on many boats, with success.

John,

You are right that leaks from skylights and ports are from poor techniques and material. But the reality is that quality ports and skylights are more expensive to buy. You have a very limited budget. You want to spend the money as wise as possible. Anyhow, Good Luck with the project.

Hi Roland,

You are absolutely right, in my opinion, buying high quality hatches and ports is being wise. Our whole concept is save money on fancy and unnecessary features and then put that into gear and construction that will result in trouble free sailing and low cost of ownership.

For example, I would guess that we can pay the extra for good quality hatches and ports (as long as we don’t have too many) and great hull construction, and good deck fittings for the price of the twin wheels fitted on some of our competitors.

Hi All,

First off, thanks very much for all the thoughts and comments on this knotty problem.

Based on the input here, a long and very interesting Skype call I had with Matt Marsh, and the successful use of composite chain plates on may boats, including the new Navy 44s, I’m satisfied that composite chain plates are the way to go on the Adventure 40, at least for those plates that are sighted inboard.

I’m also fairly sure that the cost of composite chain plates, when produced in mass, will not be significantly more than those made from stainless flat bar stock. But even if I’m wrong about that, I would still lean toward the composite solution since it is the best alternative when measured against our goal of providing a trouble free boat with a low cost of ownership.

Having said all that, of course we might run into problems I have not anticipated (like those Richard (RDE) has brought up) when we actually come to engineer a solution that will work in mass production, in which case, a rethink will be in order—that is always the way.

But for the moment, all inboard chain plates, at least, will be made from composites and we can now move on to other things.

Hi to all.

I love to embrace the new but surely a proper cruising boat should repairable worldwide with simple tools and low technology. If I were younger I would build a Fay 40. May even follow Paul Fays design to the letter and use a junk rig. Solves all the problems created by complex designs. This dialogue is very good reading, and maybe get us ‘die hards’ thinking of the alternatives.

Hi David,

For me, I would rather have a chain plate that won’t need fixing for the life of the boat, rather than one that can be repaired in remote places. Since we will engineer the chain plates with a significantly higher fail load than the standing rigging itself, I really can’t see any likely scenarios that would result in a chain plate repair.

Yes, the junk rig is interesting, but it does have two big drawbacks: it’s slow and the chafe eats you alive. This is first hand information in that when I was sailmaking I, on the insistence of the owner, made a complete set of junk sails for a Herreshoff “Marco Polo” type three masted schooner. We fussed with that rig for two years trying to make it satisfactory, before the owner scrapped it and went with the rig Herreshoff had originality designed.

I’m not saying that the Junk rig is wrong for everyone, but if you rig a boat that way, to get the advantages of instant reefing, you need to be someone who is happy with passages that take a lot longer and with constantly working on the rig and sails to keep ahead of the chafe. Just read the voyage accounts of anyone with this kind of rig to verify what I’m saying here.

For me, a sloop or cutter with good slab reefing makes a lot more sense.

I would have to disagree on using bronze before Titanium. Titanium (if you were forced to use a metal) is superior in almost every single respect over almost any other metal. It does solve one issue and that is the corrosion and rust problem with commonly used stainless. if you could solve the leaking issue, titanium would certainly outlast the entire boat and you!

Hi Murry,

I never said that titanium was not a good metal, just that it did not solve the problem in a cost effective way in this case.

By the way, titanium in and of itself is not necessarily the best metal for every situation. Witness the titanium keel that failed on the Open 60 “Safan”.

I’m no metals expert, but to say that titanium is just plain better than bronze may not be accurate. It depends on the application. For example bronze is, I believe, less likely to fail due to brittleness than titanium.

Bottom line, no matter what material you use, you have to get your engineering right at a price that works for the project in hand.

I may be mistaken but aren’t metal chainplates often part of the lightning dissipation system on many sailboats? If so, would some additional conductive material material need to be added to the shroud ends ?

Hi Paul,

A good point, and something we will have to address. Having said that, it is my understanding that it is not generally a good plan to rely on your shrouds as a lightning conductor, anyway. We will need to take advice on this, but I’m guessing that a lightning rod on the mast and the mast bonded will be a better bet. Anyway, the whole issue of lightning protection and bonding will need, and will get, thought.

Ive not seen the deck layout of your boat.

Composite or any chainplates located outboard, on the sheer clamp near Bmax , are vulnerable to collision damage at the dock . When the shrouds are outboard you are also exposing your standing rigging to the dock or boats next door during a blow on the beam. When damage occures expensive structural repairs and a new topside paint job are needed.

Additionally shear clamp chainplates make crew movement forward difficult because the diagonal and shroud block their way. Moving bags of sails forward at sea becomes troublesome .

When the chainplates inboard , thru the deck, crew can easily clip into the jackline with their safety harness tether then charge forward outside the shrouds with a steading hand on the lifelines.

I see no advantage to sheer mounted chainplates.

As for composite chainplates…ss chainplates are simple to visually inspect, composite is not.

When standing rigging is inspected for flaws… all components, chainplates, Hydraulic rams, mast step, partners… must be inspected .

Be careful when transferring lightweight race boat techniques to an all purpose cruising boat.

Hi Mike,

I’m not sure where the chain plates will end up on the Adventure 40, that will be up to the designer. Having said that, I would expect them to be inboard. Rest assured they will not be vulnerable in the way you describe.

Your commitment to inspection is laudable, however there is no way for visual inspection to determine the health of any stainless steel assembly with any certainty. For example, I had a Nitronic 50 shroud fail on me just three months after it was dye tested by an expert. If you would like to understand more about why this is, I recommend this comment.

The engineering information that I am receiving indicates that a properly engineered composite chain plate will be stronger, more reliable and longer lasting than stainless steel.

Dye testing rod is a fools game. Chop the head off and re head. Visual clues are corrosion at the terminal or loss of symmetry of the rod head when you rotate it with your fingers. Rod Standing rigging with more than seven years or 70,000 miles is normaly replaced.

I’m sailing a rod boat and have covered 300,ooo miles over 20 years. The rods have been replaced 4 times. Tip cups once and chain plates once. The cups and chain plates are condemned not for any visible decent, but because the rigger could not certify them. This will also happen with composites.

In a lightning event energy must rapidly escape. Rigging is a normal path. You should discuss this with your NA.

Hi Mike,

All good points and I would agree with your 70,000 mile replacement cycle. I disagree on the seven year option since I think that the failure mode of rod is pretty much 100% cycle load driven, not time.

One other thing. Calling me, or anyone else on this site a fool, even indirectly, will not be tolerated. This is not a forum. If you do it again I will delete your comment and ban you. Sorry to be so harsh, and I’m sure you did not mean to be rude, but once that kind of language has been used by one person it has a nasty habit of spreading.

Don’t get me wrong, you can disagree with me, or anyone else, as much as you like, but no harsh personally insulting language please.

“I think that the failure mode of rod is pretty much 100% cycle load driven, not time. ”

crevice corrosion at the stem ball fitting happens at the dock…no cycling. The stem balls of Turnbuckles and backstay insulators that face upwards and trap water are particularly prone.

Hi Michael,

Good point, I agree that there is some time effect, but I think it is minimal. I know of several boats with rod that is over 20 years old without failure. Now that’s not to say that I’m recommending a 20 year replacement cycle, but for a boat that does not get a lot of use, I think seven years is overly aggressive.

We have a steel boat , but the chainplates are all 2206 duplex s/s.

This is both stronger and much more corrosion resistant than 316.

I’m resurrecting this thread because I’m getting ready to replace the through-deck chainplates on my 1979 Pearson 10M. There’s a good conversation here about how to incorporate them into a new build, but only a few tantalizing references to retrofit. Is there anybody out there that’s done the math and testing?

I know this is an old post but I was wondering what opinions were out there regarding using a material such as g10 which could be purchased premade and installed in much the same way as a conventional chainplate. Perhaps with fg reinforcements in addition to bolts. It would appear at least in tensile strength g10 is similar to SS. Perhaps a little less, (38,000 psi yield vs 42,000 psi) however, that could be compensated by going a little thicker on the chainplate. Especially as many chainplates to not fill up the toggle gap that attaches to them as they should. You would get the advantage of having similar materials all of which are corrosively inert.

Hi Erik,

I wasn’t aware that G10 was that strong but, assuming it is, I don’t see why that would not work. Then again, I’m not an engineer so there may be something about the material that disqualifies it that I don’t know about. What I can say is I have never seen a fibreglass chain plate, although I have seen carbon ones, so I probably would not want to be the one to experiment.

Hi John,

I am writing to ask about my chainplates (aluminium, welded to the deck and the stringers below), and this seems to be the best place. The clevis pins have not been removed for about 20 years, and are now quite stuck, having corroded themselves in place (i.e. the hole is clogged up with aluminium oxide around the pin). I’ve managed to remove one over several days with patience, lots of penetrating oil, heating the chainplate whilst cooling the pin, vinegar, and some larger swings of a hammer directed at the pin. The hammer did manage to do the trick, but there are 8 more, and they all have a lot less swinging room. Also, I am a bit nervous about damaging my chainplates in the process.

Do you have any suggestions for how to best proceed? More of any of the above? Or are there any specific tools I should be looking at? I could see for example that a strong rod of metal that just fits through the hole for the cotter pin could be used to apply a torque to unstick the pin by twisting.

If you have some ideas for how to prevent this in the future, that would also be great. I thought about gluing in a stainless bushing with some epoxy, but then I worry that this adhesion will create a weak point. Perhaps I will just coat the pin in tef-gel…

I’ve attached a photo for context. Many thanks!

Hi Alwin,

I was faced with the same problem when I bought the M&R 56 30 years ago.

What I did was have a machine shop make me a press in the shape of a square out of heavy flat bar steel with a fine threaded bolt in one side and a hole to accommodate the pin head opposite. Any good machine shop will be able to make you one if you take them pics and dimensions.

Worked a treat in conjunction with penetrating oil left for several days between applications. Much safer, I think, that beating on it which may stress or bend the chain plate. Also be careful about applying too much heat since that might, I think, change the characteristics of the chain plate alloy, although I don’t know that for sure.

I then replaced the toggles and pins and reassembled with Tefgel and never had another problem.

Hi John,

Many thanks for your reply, and happy to hear of your solution. That sounds like it should work!

Best,

Alwin

Hi again John,

Reporting back as after several rounds of penetrating oil, the press I bolted together is not moving anything. I suppose most likely the issue is the gauge of steel (3mm) – it is bending significantly. I will try doubling it up for now, and we’ll see where that gets us! Do you remember what thickness you went with?

Hi Alwin,

Yes, that’s no where near a heavy enough gauge to take the loads. As I remember we made ours out of 1″ thick steel bar stock and welded it. And remember that stiffness scales by the square of thickness, so, for example 3/4″ is much less stiff than 1″.

Hi John,

Thanks for the rapid response! I will go with that then.

Hi John,

Still waiting for the bigger press. In the meantime, I’ve got a related issue to deal with: The screws holding the jib track onto the deck (blind threads into welded thickened sections) appear to be held down by the pressure of the surrounding expanded oxide more so than thread. Taking them out obviously breaks that bond, so I only see four possible solutions:

1. Leave them in place and postpone the problem until the track eventually has to be removed, hoping the pressure of the oxide and remains of thread provide a sufficient bond

2. Take them out and hope that the remains of thread will hold when putting them back (with fresh duralac/tef-gel of course)

3. Take them out, redrill and retap to a larger thread

4. Option 3, but fitting a helicoil.

What would you suggest? I’ve attached a photo of the bolt just to illustrate the degree of lack-of-thread.

In the end, we were able to extract the pins with relative ease with the tool shown in the image below (made from grinding out a fork from a wedge designed for smashing up bits of concrete). Turns out the trick is to pill instead of push – that way, you are elongating rather than compressing the pin, which very much helps it exit the hole.

Hi Alwin,

Glad to hear you got them out. I had never thought about the difference between pulling and pushing. A good thing to learn.

That said and for others considering this. Be very careful to protect the chain plate while prying the pins out since dents and dings in said plate will, as I understand it, cause stress concentrations that can weaken the chain plate, although past my pay grade to estimate how much.