We recommend that those who voyage offshore or dream of doing so take the time to do some racing, preferably offshore.

Now I’m not suggesting that racing, and particularly ocean racing, is for everyone. In fact, despite having done quite a bit of it, or perhaps because of that, I have a fair amount of sympathy for those that say such pursuits are only for the seriously unhinged. In fact, on Morgan’s Cloud we have a saying when things are nasty and uncomfortable: “Could be worse…could be racing”.

But here is an example of why doing at least a bit of racing may help you enjoy your cruising more:

The Passage

Three weeks ago (mid-October) we were crossing the Gulf of Maine from Nova Scotia to Maine. This is an overnight passage of about 170 miles that, although I have done it scores of times, I still treat with great respect because the entire track is subject to substantial current due to the world-record tides flowing in and out of the Bay of Fundy. There are some areas, most notably off Cape Sable, where the tides can run in excess of 4 knots, and even a 25 knot wind blowing against that much tide can generate a dangerous breaking sea.

The Strategy

Our preferred strategy when heading west, is to leave Nova Scotia in a calm with the tide under us and motor around Cape Sable to avoid either beating against the tide, a profitless endeavour, or beating with the tide under us, at best uncomfortable and at worst dangerous. (Of course the best option would be running with the tide under us, but that requires an east wind, which at this time of year will likely be a northeaster blowing gale force.)

As we left Shelburne in a dying northwest wind with a high pressure moving through, I was feeling pretty smug at my planning prowess. A bad situation for Phyllis who was, as usual, a captive audience for my crowing. I only got more insufferable as the wind died and we motored around the dreaded cape in a flat calm with no fog. (Cape Sable has the highest incidence of fog in the North Atlantic.)

And the forecast was for the wind to fill in from the southwest, which would give us a lovely reach all the way to Mount Desert Island (MDI), Maine. See how incredibly smart I am? (Now you know what Phyllis must put up with.)

The Reality

But not so fast. Due to an un-forecast kink in the back side of the high, the true wind filled in at 15-20 knots, gusting a bit higher, from just north of west—just 20 degrees off the port bow when we set course for Maine. Some years ago, in my macho phase, I would have put up all working sail and puked my way (Phyllis does not suffer from seasickness) to Maine into a building tide-enhanced Gulf of Maine sea.

But the smarter, or at least older, John hoisted the main to steady her and motor-sailed, which let us get within 25 degrees of the wind instead of the 50 that we would have achieved, when you include leeway, under sail alone into the steep chop. For several hours we punched into it on port tack at about six knots, not quite laying the course to MDI, but within 10 degrees.

The Tactics

The forecast was still for the wind to back to the southwest and I could see just a hint of cloud in the moonlight out to the south. As we pounded along, I was thinking about the two options open to us:

- The obvious one of continuing to sail on the tack that pointed us closest to the destination.

- Tacking onto starboard toward the expected new breeze.

An additional 10 degree shift to the north, which I was pretty sure was temporary, crystallised my decision: we tacked to starboard. Not an easy decision to make when it meant heading the bow further away from the destination, thereby reducing the velocity made good (VMG), as read off the GPS, to only a knot or so.

The Payoff

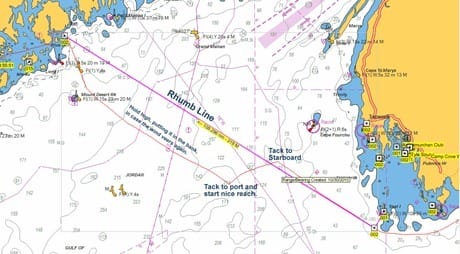

Two hours later the wind went southwest, a great development for us since we were, by then, well out to the south (see chart above). We tacked back onto port, shut down the engine, unrolled the jib and cracked off on a booming 8 knot reach, arriving in Maine just before noon. The only drawback about my decision to take a tack to the south, at least for Phyllis, was that it put me firmly back in smug mode. (The same strategy would have worked without motor-sailing too, although we would have been a couple of hours longer due to the wider tacking angles.)

I was smugger still when I discovered that another boat on the same passage that had stayed on port tack, was so far to the north that when the forecast shift finally turned up for them, they were hard on the wind, motor-sailing all the way to MDI.

The Point

The point of all this gratuitous boasting is that there is very little information circulating in the cruising community about this kind of strategic planning and tactical execution. That’s a pity since getting a series of decisions like this right can make all the difference between a pleasant sail and a nasty slog.

Am I always right in these situations? Of course not. But years of racing—where making the wrong call puts you dead last and the right one in the glory, and let’s face it, us guys love the glory—has given me enough experience that I’m right a great deal more often than I’m wrong.

So, if you are a cruiser (or an aspiring one) that has never raced, do everything you can to get a crewing position on a race boat and watch the tactics used and their results carefully. Even a year or two of racing will teach you more about getting from here to there as quickly and comfortably as possible than reading a bunch of books, or for that matter, this post.

What do you think? Is a racing background a good idea for a voyager? Do you have a story in which racing tactics improved a cruising voyage? Please leave a comment.

If you are wondering about the red racing dinghy in the photo, it’s an International 505 that we found languishing in the back lot of a boat yard on MDI. I raced 505s for years—before going badly nuts and taking up ocean racing—and can testify that sailing a 505 is simply the most fun you can have with your clothes on.

Hi John:

I think even informal racing, sometimes even with boats you don’t know, is a good way to sharpen your thinking and planning skills, which in turn makes you a better and safer sailor. Several years ago in Maine, Philadelphia Sailing Club had chartered a J46 and a J44 with racing keel so the boats were pretty evenly matched as we found out in a crossing tacking duel the wrong way down Eggemoggin Reach. My good friend Bill and I were the two skippers. And, as any time we were on separate boats on the same water – principally the Chesapeake – a race was almost inevitable. Later in the week, we were coming back from Matinicus and heading for Winter Harbor on Vinal Haven. It was a bit foggy and the light winds were behind us. Both of us started out wing on wing, and were drifting and bobbing more than sailing. I got bored and decided to head up to starboard to take a look at Isle au Haute where Linda Greenlaw (of Perfect Storm fame) is from. I would love to claim it was intentional, but it may have been intuition or an unconscious memory of the weather forecast. Anyway, the wind filled in where we were to the east and we had an increasing to 8 knot reach back toward Winter Harbor. As we converged back toward the other boat, they picked up the wind and we were soon racing almost side by side toward Winter Haven. I had momentum in my favor. Also, it is very, very important in informal racing to NOT get too excited and forget your navigation!!! The J44 had to take a quick tack out to avoid an underwater ridge, and we won handily.

Sometimes taking the “cruisers tack” can get you to your destination more quickly than sticking closer to your rhumb line. You will definitely be more comfortable. One time on the way to Bermuda, we weren’t making any headway and decided to take broader tacks – it was the first time I had heard the term “cruising tacks” – to give that a try. A larger tall ship was staying close to the wind. We tacked out and back several times and were keeping up with the larger tall ship, and I am sure we were more comfortable.

Hi Lee Ann,

Good point, put two sailboats on the same piece of water and there is no such thing as cruising. And every such tussle, as you point out, adds to our skills.

Having been bitten by the ocean racing bug in recent years, I agree that there are many potential benefits for cruising sailors who try their hand at racing, well beyond the tactical lessons associated with positioning your boat to take best advantage of anticipated wind shifts (good job, by the way!). Racing “forces” one to learn (or at least try to learn) how to sail and sail well in conditions that many cruisers would normally choose to avoid sailing in — at the light end as well as the heavy end of the wind spectrum; hard on the wind as well as off the wind. Racing boats are usually set up and rigged in innovative ways designed to make adjustments to sail trim easier; cruisers can often adapt these innovations to great benefit, but may not be aware of them if they haven’t been exposed to them through racing (or at least paying attention to racing). Many racers are fanatics about keeping excess weight off their boats, and maybe experiencing how much better a lightened boat can sail, or how much easier it is to work on a boat that is free of excess clutter, might prompt some cruisers to consider putting their own boats on a diet and exercise regime. Racers often sail and maneuver their boats in very close proximity to other boats, the experience of which might help cruisers with getting their boats in and out of tight marinas or crowded anchorages, and might help them evaluate crossing situations and collision potentials. The attention to offshore safety issues given by most ocean race organizers is another area where many cruisers could potentially benefit from experience participating in such events. Racing can also just be a lot of fun (especially if you’re on the right boat with the right skipper and crew…)

Hi Tim,

Good point that the great lessons taught by racing go far past tactics and strategy. Even after the race is over there are valuable lessons learned: For a couple years I sailed an E22 out of a berth in a crowded marina. The task of sailing her back into the berth without hitting something and doing it quickly to place well in the most important race of the day, FIB (First In Bar), really sharpened the boat handling skills.

Likewise, 20 505 dinghies converging on the wing mark on a screaming three sail reach, all trying to get the inside position on the jibe. One guy who crewed for me used to add to the excitement by screaming “we’re all going to die” repeatedly in the final seconds—not sure if he was trying to intimidate the competition, or me.

John

Agreed! An addition to this. Windsurfers.

I learned to tack & jibe on a windsurfer in an afternoon. This one experience dramatically changes how I sail my boat. Windsurfers have no rudder. Steering is by changing the center of sail relative to the hull. It is that simple.

This makes rudder-steered boats look a lot more complicated. What if we try to take this complexity out of the equation? Take the rudder out of the picture & steer the sailboat like a windsurfer?

I applied the insights learned from the windsurfer to my boat, a full keel, heavy displacement ketch. I find it very easy to go upwind, reach & run (to 45 degrees or so of true downwind), just by setting the sails & sheets. For example, once I ran downwind between Iceland & the Faroes for 18 hours, the wind on the quarter, the wheel untouched, the course adjusted solely by setting the mainsail or genoa sheet. My boat has a wind vane & autopilot. Have yet to use either.

So, in steering with sail only, the rudder is taken out of the picture. It dangles free. It is in the position of absolute minimum drag. Steering with the rudder means constantly increasing its drag factor, which reduces hull speed. This drag could be a LOT. Water is heavy. Slicing through water at speed means a rudder laid over to one side is going to create a lot of drag.

So here we now have 2 ways of steering. Let me compare. Steering by rudder. The sails are set at maximum efficiency, but the rudder drags. The boat is in a state of contradiction. She is not in a state of grace. Steering by sails/sheets only. Sails are not set at max. (With practice I set them close to max pull.) But the rudder no longer in the picture. It hangs free. No drag. The boat has no inner contradiction. She is now in a state of grace. I can feel it – a flow, an elegance, a rightness.

Which method is faster? I have not used GPS to determine which method is faster.

When the boat steers herself, she is always constantly responsive to changes in wind. When the direction changes she instantly feels this and responds. She is always at maximum sensitivity relative to a changing wind. It is impossible for a helmsman to attain this level of sensitivity to change in wind direction. This alone is a big plus for steering by sails/sheets.

This method may be faster.

Its hard for friends who come along for a sail! They typically have the modern fiberglass boat which seems to need constant steering. They always want to grab the wheel of my boat! They seldom understand what I’m trying to do here. It is just too different a way of thinking!

Steering the boat like a windsurfer is a different paradigm. It requires regearing how one understands how to sail. All this arose from a single encounter with the windsurfer. While irrelevant for tactics, it opened up for me a totally different dimension in sailing.

Nick

39′ Colin Archer ketch

Hi Nick,

Well the first thing that strikes me is that you have much better balance than I do. It took me many afternoons to master a wind surfer and I never did get the hang of jibing.

But I think your point about balance is really good. Powerful autopilots can make us very lazy about making sure that the boat is balanced correctly for the conditions. We have a rule that there should never be more than 1/2 a turn of weather helm on the wheel.

John,

Thanks for such a well presented article and theme. Competition is a big filter for me, separating out those things I think I know well—but don’t—from those that have become instinctual. So yes, bring on the racing to cement the skills and expose the flaws.

Thanks again,

Jeff

Nick; The happiest marriage of those two approaches is to be able to change the relative centers of effort between above and below- eg centerboard(s) or flexible rigs or shortening a divided rig- thus trimming sail well and shifting their c of e for course. Hull shape- beam particularly- determines a steady or unsteady course as heel increases (eg when to reef). I used to be mostly unbeatable in light air down wind racing small boats as I would use weight alone to steer- no rudder- mostly to induce asymmetry to the hull. In short, I agree with your approach.

Following Nick Katz’ suggestion about steering with sails depends on the boat. It works well on a Pearson 35 and a Bristol 45. Each has 2/3 footed keel and centerboard and a conventional sailing rig (main and genoa or staysail). But does not work on my current Freedom 36′—unstayed mast well forward, large main, small self-tending jib, fin keel, and spade rudder.

And—having the temerity to dispute a portion of John’s response about not allowing a weather helm of more than ½ turn of the wheel: I try to keep a limit of ¼ turn. Needing more than ¼ turn is my signal to take another reef. In strong windward conditions, the Freedom sails faster—and easier—with more reef and less weather helm.

Hi Westbrook,

Really good point about the type of boat being critical. Boats like Nick’s Colin Archer are famous for how well they will steer themselves.

Morgan’s Cloud will self steer on the wind down to a beam reach, as long as the wind is not too fluky. Off the wind, it would get scary.

I think the part of a turn that signals a reef or some sail trimming is dependent a lot on the ratio of wheel turns to rudder movement, so probably not directly comparable. A quarter turn on MC represents the minimum “bite” that she needs to go upwind well.

My 22′ catboat is similar to the Freedom- appropriate reefing is extremely important. I am building a bowsprit currently that will carry, among other uses, a small self-tending jib. I have no illusion that this will be very meaningful in combating weather helm- with my 10 1/2′ beam. A barn door rudder really makes the braking effect obvious…

Totally agree Sal & I sail around the Brittany coast in France where we have tidal range of 13 metres and currents of up to 9 knots. The worst we did was F9 on a beat into 8.3 knots tide (WOW) yep the waves were huge but in our Colvic Watson 32 at 20 tons we just bash through it. I have on occasions taken people on a friends yacht through the Sept Isles passage on the Ebb in a Westerly F8 just to show them that it can be done safely but wouldn’t recommend it to a novice. They say it’s these tests that make us better sailors but I recon better sailors don’t look for them. He He He

Done racing…but the instinct is still there.

Hi John

Rookie Marblehead to Halifax navigator here. Hoping to tap some local knowledge re: inshore versus offshore currents from Cape Sable to Halifax, typical wind patterns, do’s, don’ts, etc. Grasshopper seeking Master’s advice. Cheers

Hi Sparky,

Wow, to do justice to that question I would need to write a book, not a comment.

Ocean race navigation is complex enough, add in the currents around western Nova Scotia and it gets to the equivalent of Phd level.

I would start with the basics and read a couple of good books on racing tactics. Unfortunately, I’m out of date, but back in the day when I was a race navigator, Tom Whidden was The Man, and I see that you can still get the book he contributed to: https://www.amazon.com/Championship-Tactics-Anyone-Faster-Smarter/dp/0312042787

The other piece of advice is don’t over rely on computer tactics software in the area but rather make sure you have a paper copy of the current charts for Cape Sable, the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine.

I will close with an old but good piece of tacticians wisdom: when faced with the choice of heading for good winds or good currents, winds win most of the time.

Oh, one more thing. If you are buying tactics books, stuff by Stuart Walker really never worked for me, in fact he tended to confuse me more than educate me.

Rookie NAVIGATOR for this race, far from an ocean racing noob. I’ll try to simplify my question. What are three bits of local knowledge that would help re: coastal currents between Cape Sable and Halifax? I’ve already acquired Fundy / GOM Atlas of Tidal Currents and TideTech. Both are thin re: Cape Sable to Halifax. Cheers

Hi Sparky,

Well, if you are an experienced ocean race navigator, you know that every race is different so skill analyzing the conditions and executing good tactics and strategy will win the day, not local knowledge, which in my experience, tends to be more mythical than fact and often counter productive since, even if it’s right, it will only apply in certain circumstances.

For example, the standard tip for the Newport Bermuda race is “go west”. And yes, being west probably wins more often than not (guess) but if it’s a year where the conditions favour being east, following the tip will not end well.

Also, I have never done the race in question, so I would be reaching to presume to tell you how to navigate it.