Question: I am planning a west to east North Atlantic crossing and have read that most yachts leave in May and June. What about leaving in mid-September or early October? Is that still a possibility? Ideally I would like to cross from St. John’s, Newfoundland to Britain.

Answer: We don’t recommend autumn crossings of the northern North Atlantic. While it has been done—in one case by a 78 year old man in a 32-foot boat, albeit with a stop in the Azores—the bottom line is that most people do it in the early to mid-summer because that is the best time.

Having said that, this question has come up a couple of times lately so I’m going to write at some length about why we feel this way.

One glance at the pilot charts will show that the gale frequency goes up dramatically in that part of the world once September 1st comes. But these charts do not really communicate the size and intensity of storms that start to appear in the autumn. Over the last 15 years I have often been working my way south from Newfoundland or even Labrador or Iceland when September came. During those trips I spent a lot of time hunkered down in snug anchorages listening to the wind scream in the rigging and looking at some pretty scary weather maps showing huge low pressure systems generating gale and storm force winds covering the entire Atlantic from Newfoundland to Ireland. The really nasty systems are often the result of a hurricane that has gone extra-tropical as it tracks north—if you want to know what that feels like, read The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger.

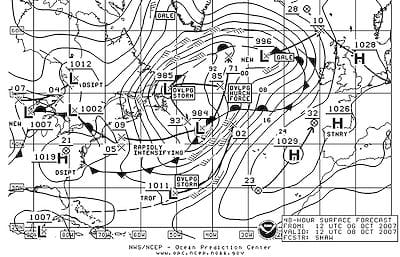

The level of gale and storm activity in the northern North Atlantic shown on this chart is by no means exceptional for this time of year. Particularly note the rapidly intensifying low that starts at 1009 mb and plunges to 984 mb in 24 hours and 971 mb in 48 hours. A storm like that is impossible to dodge, difficult to forecast accurately and can ruin your whole day. Meteorologists call lows like this ‘bombs’ with good reason. I got hit by one off Hatteras 20 years ago and the memory is still, shall we say, vivid.

While the wind speeds in these storms are pretty impressive, what really makes them dangerous is the waves that their size and duration are capable of producing. Significant wave heights of 20 to 30 feet are common and the latest research indicates that this means there are 40 to 60 foot monsters around in such a storm. It was a storm like this in September of 1995 that generated a wave close to 100 feet high that hit the liner QEII, doing substantial damage, including bending the rails on the bridge—not a survivable encounter in most yachts.

Since it is difficult to predict the weather accurately for more than two to three days and the crossing from Newfoundland to Ireland will probably take close to two weeks, a yacht and crew contemplating a fall crossing should plan for and be capable of surviving storm force winds and huge breaking seas for several days. Based on my observations over the years, my guess—and it is only a guess—is that once September 1st comes the likelihood of encountering such conditions on such a voyage are better than 30 percent—not odds that we fancy much.

There is one arguably safer option, which is to break the crossing into smaller legs that will fit into relatively good weather windows by stopping in Greenland, Iceland, Faroe and Shetland. However, only yachts experienced and equipped to deal with the challenges of Arctic cruising, including surviving storm and perhaps even hurricane force winds in remote anchorages with poor holding, should consider this option in the fall. Also, stopping at these landfalls, if it coincides with heavy weather, could be even more dangerous than staying at sea. This is particularly true of the south cost of Iceland and the Faroe Islands.