Don’t get the length of this article put you off, a lot of that is made up of photos and captions that are fascinating.

Also, many of you know Matt as an engineer, but what you may not know is that he studied naval architecture as part of his training.

Experienced old salts, those who have put a few tens of thousands of miles under the keels of a few dozen different boats, have their own words and ways to relate how a boat behaves at sea to how it’s built and shaped.

Naval architects too, have their own language and their own math to guide their decisions.

How then can the rest of us look at a yacht design and understand how it’s going to perform?

The good news is that with a good standardized way to represent the shapes it’s actually not too difficult to relate lines on a page to the feel and performance of the boat when it’s underway:

Cutting Up The Hull

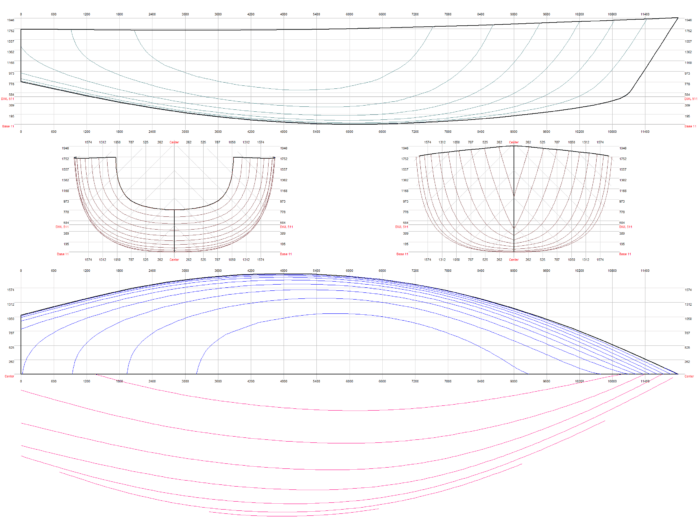

To begin with, we need a way to represent the three-dimensional shape of the hull on a two-dimensional paper or screen. For almost as long as yachts have existed the standard way to do this has been the lines plan.

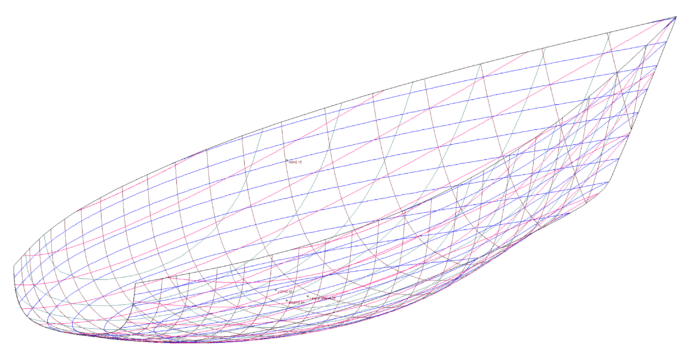

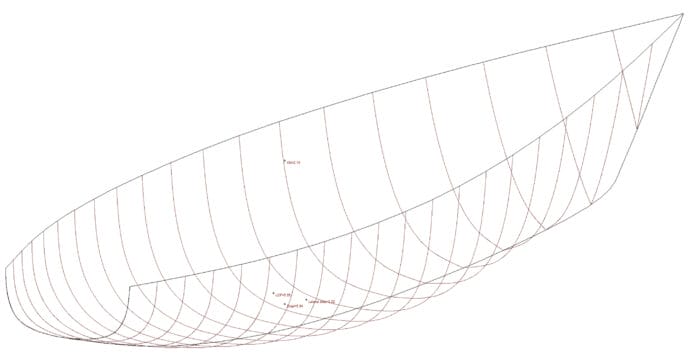

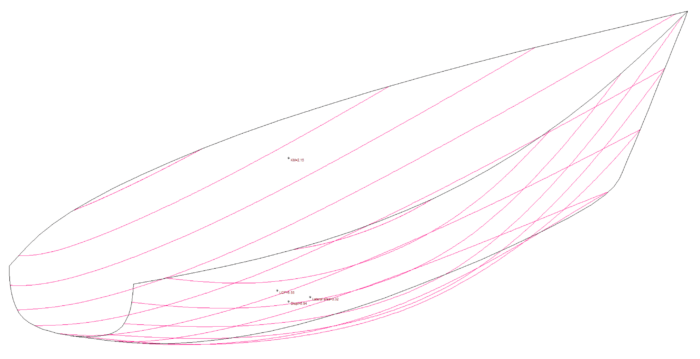

We start with a 3D hull. For today, to avoid any hint of bias towards a particular style of boat we’ll use one of the best known generic hull shapes in the design education world: the Freeship Default Starting Model, at the top of the article.

Stations

We’re going to take our boat to the bakery and put it in the bread slicing machine. First, we’ll cut it up transversely, like a regular loaf of bread. This gives us the equally spaced station lines, in brown.

Waterlines

Next, we’re going to cut it into layers parallel to the water’s surface. This gives us the equally spaced waterlines, in blue.

Buttock Lines

Now we turn our slicer vertically, and align it to the fore/aft axis. This gives us the equally spaced buttock lines, in green.

Diagonals

Those three, combined, give us all we need to make a standard 2D representation of the hull. Many designers, though, will now turn the slicer to an angle (usually, but not always, 45°) to also give us the diagonal lines, in pink.

Put it Together

When we lay all of those out flat, we get the lines plan: a clean, intuitive way to accurately represent the shape of the hull.

The Payoff

Okay, but how do I go from “what the hull looks like” to “how the boat will behave”?

Good question. An old salt1 will talk about “hard bilges” and “stiff motion” and so on—language that someone new to sailing might have a hard time parsing.

A naval architect will go on about “metacentric height” and “area moments of inertia”—equally impenetrable to someone new to the field.

Let’s look at each element of the lines plan, and its effect on the boat, in plain language and then relate that to photos of boats:

Fascinating article which reads very well together with an earlier one by Eric Klem concerning weight distribution. Both have improved my understanding of why my boat behaves as she does and I now understand much better what I should (or should not!) do to improve it. Many thanks to both authors as well as John for such clear explanations.

Great article, clear concept, very clearly written. Well done!

Agree Agree, This is a great explanation of hull design and how it effects a boats behavior at see . Look around the current offerings from notable sea going boat manufacturers and you know they are no longer building good sea boats but great dock condos and weekend cruisers , I guess thats the majority of the new boat buyers out there nowadays. We have a Bristol 45.5 great offshore boat but some people don’t like the center board.

There’s nothing wrong with centreboards as long as they’re well designed and well made.

The design spiral / optimization process looks somewhat different for an offshore boat, versus one that is intended for marina and weekend use.

If you’re designing a bluewater / long-range cruising boat, you first set the displacement and volume (gross tonnage) according to the cost and capacity (i.e. cargo weight and crew complement) targets set by the client. Then you select performance ratios and coefficients according to the design goals and the full range of possible weather and sea conditions. Then you see what length, beam, rig area, and proportions come out of the optimization math.

If the boat is intended to spend 95% of its time at a marina and the other 5% in benign conditions, you start the design with the target cost and length. Then you consider the speed capability in light to moderate conditions, and try to maximize the interior volume within that limiting length. Then you try to optimize all the rest of the parameters and proportions within those constraints.

Or, if the boat’s intended for racing, you list all the constraints of the race rule in question, look at the wind and wave conditions that are likely to prevail, and then try to maximize speed for those conditions within the rule’s constraints.

All of these approaches are valid, but they lead to very different boats. Boats resulting from the harbour-queen approach do not fare well in offshore conditions – just as boats designed for offshore use tend to be frustratingly expensive to moor, relative to their accommodation capacity, if kept in classy downtown marinas. Similarly, boats that are built to a specific racing rule tend to be expensive to maintain and uncomfortable to live aboard relative to their cruising cousins.

Yes we actually love our center board . Ted Hood designed a good system that has worked for decades with out trouble, but everything has it limits . You still need to keep an eye on anything that’s 40 years old. Cables and sheaves need to be replace at some time .

The only issues I have with the current yacht manufactures is they are calling there boats “blue water” boats . There really should be some sort of grading program for a yachts usage . Just to help keep people safe . Its not easy to choose the proper boat for the job if you haven’t made the investment in time to understand what makes a good “blue water” boat.

On a different note , strange how there were so few sailboats at the Toronto boat show , I walked by the one Beneteau’s bow you took a picture of. Next year there will probably no keel boats there.

Your article is a must read for anyone trying to figure out what they need , not everyone wants to go offshore/off-grid.

Are you a yacht designer Matt ?

There is a reasonably good grading program for yacht usage: the CE RCD 2013/53/EU design categories A through D. That Beneteau Oceanis 30, for example, is rated B6/C8/D10 — meaning that it can carry 10 people in wind and waves of no more then Beaufort Force 4, can carry 8 people for inshore/coastal hops in Force 6 or less, and can make short offshore passages with up to 6 people provided that conditions will not exceed Force 8. It is explicitly *not* suitable for “any waters” navigation or for use on any passage where there is a non-zero chance of exceeding Force 8.

Offshore cruising boats, by definition, fall in cat. A and we, as buyers, can safely reject anything that has a cat. B, C, or D rating if we are considering an offshore passage. From the set of cat. A boats, we then evaluate each against the selection criteria in this Online Book.

RCD categories are not perfect, and older boats don’t carry the ratings, but they’re the best we have industry-wide right now.

Yes, Toronto was really disappointing for sailboats. No large ones, only three midsize ones, and a bunch of dinghies. But, hey, twin Verado 400s on everything else, right? I think we’re going to go down to Maryland for the fall sailboat show in Annapolis to get a better look at what’s new this year.

I am skilled in yacht design but I am not currently practising in that field. I got tangled up with an early-stage laser technology startup about a decade back, and have had my hands too full growing that business to spend much time on new boats.

Great article. Concise and well written. I have volumes on the subject in my sailing library. This summation tops them all.

Thank you, excellent article.

I want to offer one trick to get a feeling what weather helm might look like, especially in light of a autopilot helming the boat. Draw a waterline at 30deg heel and evaluate the distribution of area of that plan. I would also suggest “Preliminary Design of Boats and Ships” by Cyrus Hamlin.

Thanks Matt… great overview!

I was wondering if there are examples of boats with a close to plumb bow (longer waterline) but still relatively v-shaped forebody stations. I see many with plum bow and u-shaped… and many with a decent overhang and v-shaped. Do they have to be correlated this way?

Also, how would you characterize the scow bow seen on some new racing boats? Is this essentially the u-shaped forebody taken to an extreme for downwind / surfing?

At the moment, I can’t think of a common boat that has a V-shaped forebody below the waterline AND a plumb bow. It’s certainly possible; Nigel Irens’ Ilan Voyager comes to mind. Few builders are willing to give up so much interior volume in the bow, though.

The advantage of a plumb bow is that it maximizes waterline length within a given overall length, thus reducing wave-making resistance, and therefore yielding more speed in conditions where the boat is powered up but not yet needing to reef. Lengthening the waterline, though, adds wetted surface area, which increases skin friction, hampering low-speed light-wind performance. Choosing U-shaped sections is a way to minimize this increase in wetted surface. A plumb bow with a V-shaped underbody would yield a very high wetted surface area, and so would need a fair bit of wind to outperform its U-shaped sibling…. and, by the time you have that much wind, you’re probably in waves big enough that you’ll prefer to have the bow overhang and the topside flare to keep the spray under control.

As for scow bow racers: Recall that high-performance boats with pointy bows and wide sterns tend to have helm balance that varies dramatically with heel angle. Making the boat wider up front is a way of restoring fore/aft symmetry, increasing the form stability that’s needed for sail-carrying power, and reducing the tendency of a pointy-bow, wide-stern boat to change its yaw behaviour as its heel angle varies.

When a boat is on plane in small waves, the bow is clear of the water and the bow shape doesn’t matter. So, if you have an overall length constraint and will always be going fast, why not chop that part of the bow off entirely, save weight, and have the remainder of the boat perform much the same as a boat that’s 20% or 30% longer? It works great, until the waves get higher than the gunwales, and then you have all the pounding and discomfort downsides of any other boat with tremendous flare and very flat forward sections.

Thanks for the detailed response. Interesting to think of the scow bow as a truncated normal one. Appreciate you going into the tradeoffs here.

The radical scow bow (Revolution 29) is certainly eye catching.

It’s sad that such craft are faster than 8 meter yachts while being almost as ugly as the 8m is beautiful

Of course, comparing usable interior volumes…

Choices, choices !

Fine summary. Well done.

Top stuff, Matt! Excellently and understandably argued.

Best wishes

Colin

Thanks for the great article Matt, and great choice of images to go along with it!

Thanks for the article Matt, cool to be learning new stuff on this wonderful site. Some clarification please.

I am trying to understand diagonals as they apply to a Beneteau 473, LOA 14.5m, beam 4.3m, approximate beam aft at deck level ~ 3.8m (excludes the sugar scoop), but at the waterline is ~ 2.0m aft (~ 1.25m at the sugar scoop). A single spade rudder.

The hull is also reasonably rounded forward and aft with no chines, so she pounds if sailed hard upwind into big steep seas. The flip side is she will surf off the wind at 12->15 knots with immaculate manners and “two-finger” steering.

Yesterday we sailed close-hauled for two hours into TWS 15 knots, gusting 25 knots, 15 degree wind shifts, and accompanying waves. No one touched the steering wheel and no autopilot engaged – beautifully balanced upwind with the boat slowly luffing in the gusts and coming back to course in the lulls. Downwind…not so much.

Running (but not surfing) in steep following waves especially offshore (2m+) we are thrown off course easily and she needs very active steering. We have tried goose-winged and twin headsails, but nothing really helps.

So we don’t run in big waves, rather we tack down wind when the steering is much easier, our VMG (negative) is significantly higher (30%+), the ride much more comfortable. When we surf the steering goes super-light, the boat comes more upright and it’s like we are on rails.

I always thought the issue with running, was short steep waves/swells lifting and plunging alternate overhangs aft, causing us to roll and then veer off course, much like a displacement kayak in waves. Is this because we are alternately unbalanced as we roll, or we are unbalanced so we roll and veer off course?

Are we just better balanced pressed over to one side on a broad reach (say 10 degrees), bringing our waterline form closer to a more stable equilibrium fore and aft?

Such behaviour when on a dead run is, as I understand it, quite common in shallow-bodied, broad-sterned boats of that general type.

That’s a hull which is intended to develop stability from the buoyancy of the outer aft sections as it heels. As you’ve observed, this can be done in a way that yields decent balance with the wind ahead of the beam, as well as exhilarating speed when on a beam reach or broad reach. On a run, without any heel angle, one would expect that following seas would behave…. well, exactly as you’ve observed. A wave passes under the port quarter; the broad stern translates that into a lot of buoyant lift at the port quarter; the boat responds with a coupled down-pitch, starboard-roll motion; aggressive helmsmanship is required to prevent that roll-pitch motion from inducing a yaw motion as the bow digs in and the stern tries to go sideways. Coming up to a broad reach and trimming in the main and jib sheets puts enough lateral pressure on the sails to heel the boat just a bit, and get her back to a state where the forces are properly balanced.

Essentially, your Beneteau’s designer (Jean Marie Finot, if I’m not mistaken) has chosen to sacrifice comfort and balance in a rough seaway in favour of making the boat about 20%–30% faster, assuming light to moderate wind and sea conditions, than it would be if it had been optimized to eliminate this undesirable dead-downwind behaviour and to not pound upwind. This same design decision made it possible to fit two large double quarter berths, rather than single quarter berths. It is an exceptionally light boat (DLR = 129) but is modestly powered (SA/D = 17.5). I would say that it is a good hull design for its purpose — i.e. providing much of the helming and sail-trimming fun of a race boat, without the risk and expense of a severely overpowered rig, and with the capability to do extended coastal cruising and fair-weather passages in a suitable standard of luxury and comfort. It does not appear to be intended as a heavy-weather bluewater, high-latitude, or remote-region boat.

Thanks for the detailed reply Matt, understanding adds to knowledge…!

Yes, the 473 was Groupe Finot designed and I was told, a shortened version of their successful Whitbread 60 hull. The standard masthead rig provides ample power, although a taller mast was an option.

Our 473 came from the factory with the one double guest aft cabin to port and a single crew berth and utility storage area to starboard, plus an extended galley and wet weather gear storage.

We wouldn’t venture south of NZ in our 473 (apart from likely facing mutiny), although these Oceanis boats have thick hulls (last of the hand-laid Beneteau boats) and massive U beam floors with big flanges securing the keel.

Many Northern Hemisphere 473s arrive in NZ every year and the boats seem to stand up to this well, talking to the crews we meet. It is trade-wind sailing I suspect they were optimised for, and in which they really excel – 200 nautical mile days being readily achieved. Our record is currently 220 nautical miles in 24 hours, and I suspect 250nm would be quite possible.

Cheers.

Perhaps this is beyond the scope of your article on hull design, but I would suggest that pitch moment of inertia (also expressed as pitch gyradius) plays into motion comfort considerably. You have only alluded to it with the mention of long overhangs being more sensitive to the effects of added weight. While low pitch moment of inertia is generally desirable for performance, it may not always yield the best pitch accelerations for comfort. Of course, it cuts both ways, and higher pitch inertia can lead to pendulation that can stop of heavy boat in its tracks as well as be terribly uncomfortable. One other point concerning LWL and it’s effect on displacement mode performance. A long waterline without sufficient submersed volume may not be as effective at high Froude numbers. In other words, not all LWLs are created equal. A bow profile with large overhangs but a deep forefoot will have very effective LWL whereas a plumb bow with shallow forefoot will be far less effective. I take LWL with a grain of salt because it doesn’t tell the whole story where “hull speed” is concerned. Thanks for the anecdotal piece.

Eric addressed weight distribution and moments of inertia very nicely in an article a few months ago:

https://www.morganscloud.com/2023/09/08/how-weight-affects-boat-performance-and-motion-comfort/

So I intentionally omitted it from this article on hull shape.

Regarding “A long waterline without sufficient submersed volume may not be as effective at high Froude numbers.”

This is precisely why the prismatic coefficient (Cp) is so important when specifying a hull shape. At higher Froude numbers, you need less volume at midships and more volume in the ends, i.e. a larger Cp, to get a proper match between the underwater distribution of hull volume and the lowest-energy wake profile.

Good stuff. What the heck is going on at the stern of that swan 47 Gimme Shelter? It looks like a hall of mirrors down there. That’s definitely not normal.

Hi Pete,

True, more on how that happened here: https://www.morganscloud.com/jhhtips/the-ior-rule-has-a-lot-to-answer-for/