It was moonless and black dark. My 45-foot sloop was close reaching in a world of breaking wave crests and flying spray into 25 knots of wind generated by an approaching cold front.

I had just risen from a sodden bunk aft and was inching my way forward to the head, not sure whether my mission was to pee or puke before going on watch. As I passed my friend James, curled into the lee salon berth in a strange shape demanded by trying to avoid the worst of the water raining down on him from the port above, he whined, in imitation of a child on a long road trip,

are we there yet?

I laughed so hard that I nearly wet myself and completely forgot about puking. Ever since, that phrase has become the standard tension-breaker on my boat whenever things have got uncomfortable at sea.

It’s even funnier once you know that we were first night out on a five-day passage from our then-home in Bermuda to Newport.

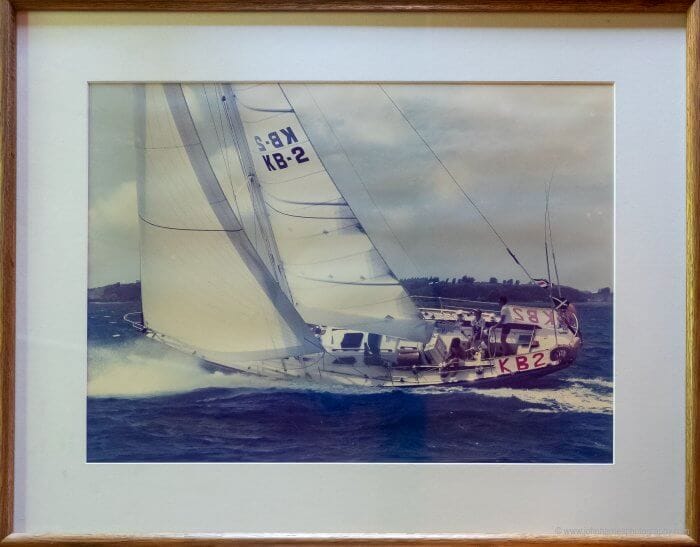

For the balance of that passage we slept in sodden bunks while listening to ominous creaking as the old and tired ocean racer bent and flexed—the reason that every port, hatch, and deck fitting on the boat was letting in a goodly portion of every wave that broke aboard, despite having been watertight when we were sailing in sheltered inshore waters.

And we endured the same discomfort and vague disquiet about the structural integrity of the boat for five more days racing back to Bermuda…while still having a truly wonderful time.

Yeah, it was a half-assed way to go to sea. And they sure as hell were two of the most uncomfortable and repair-filled ocean passages I can remember.

But we were out there and, at the end of it, we had done one of the tougher ocean passages around—twice—with no one getting hurt and no serious incidents.

Best of all for me, I had at the age of 36 realized my childhood dream of skippering my own boat on an ocean passage. The realization of which made me so euphoric as we tied up in Newport and headed for the Black Pearl to escape the sodden mess below that I can still remember it as if it were yesterday.

Over the next four years I continued refitting the boat to the point that she was both strong and watertight. I have written about the negative aspects of that life experience before (see Further Reading), but this article is about the positive.

Here’s the take away point. For the entire eight years I owned the boat I sailed her…a lot. I didn’t wait until everything was perfect—an unattainable goal, particularly with that boat. I took the half-assed option. And, because of that, if I sum the whole experience up, it was a positive one.

Would I do it again today? Not a chance. Am I advocating that you do the same? Not necessarily. But if you are considering refitting an old boat, here are five important things to think about about, based on my experience:

You have certainly evoked a lot of happy memories: living aboard whilst fitting out a 28 foot steel sloop. When I started it didn’t have a rig, a motor, and the fitout was just a few sheets of ply, but by the time a mate and I had finished it was a fine little ship. All this on a swing mooring whilst being a full-time student. Happy days indeed. Great Article. Thank you.

Hi Mark,

Wow, you do have a high discomfort tolerance! That said, I lived aboard the old boat while rebuilding the galley and chart table, albeit it alongside, and don’t remember that time as being terrible. But then I was a lot younger!

Good article John.

Am on a train to Southampton to visit the Boat Show to ogle boats I will never own nor wish to. But maybe I will learn something I had never before considered.

After my recent failure to buy a boat that had everything I went back through my notes on a boat I had visited back in June. I had come away thinking she was a bit shabby and sad inside and out and lacked a working autopilot/self steering gear. Not all the electronics worked although she did have Furuno radar with dual monitors. Now I took the time to write down in two columns her pluses and minuses. Confining myself to needs rather than wants I was shocked to discover the imbalance in the columns. Applying your “refit as you go” mantra there was only one item in the minus column. The plus column reached almost to the bottom of the page. Not only that, it had several items that “the boat with everything” lacked: encapsulated fin keel, skeg and top class builder.

All boats are compromises but maybe some boats are more equal than others.

Hi Mark,

Sounds like a good analysis. Good on you for separating needs and wants. Probably the most important step on the road to a good boat acquisition.

Great article John!

I had had the privilege of meeting Matt Rutherford in Annapolis a couple of years ago during a seminar he gave in the winter. Only five people were at the seminar and I was lucky enough to have one on one conversations with him. His story on the Albin Vega fits this article well. He told me stories of dumpster diving to find good plywood to fix the rotten bulkheads. Circumnavigating the Americas in a retired 27′ Albin does go to show it can be done and how much discomfort we can tolerate if we set our minds on the overall goal.

Hi Dan,

Yes, Matt’s achievement is a great inspiration to us all. That said, I would guess that Matt is in the top 0.1 percentile in discomfort tolerance, and so we all need to be realistic about what we can take when thinking about our own plans. For example, I know for absolute certain that even in my prime I would not have got more than a few hundred miles (at best) in Matt’s boat, before giving up.

Hi John,

Good article with a great deal of hard-earned wisdom.

As someone who bought a salvage boat, got her launched and going pretty quickly, and then did the refit/upgrades/troubleshooting over years of coastal cruising in just the way you describe, I will support your suggestion that offshore experience is a tremendous asset when making decisions. It took one relatively rough offshore passage (my first) to your home country to make clear that, what had been a fine coastal cruiser for my family for well over a decade, was not going to be a live-aboard sailboat to take us to far-flung places.

Like parenthood and war, offshore experience is hard to appreciate fully from a distance: you need to have been there/done that. It is a quantum leap in learning about yourself and your boat.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

Thanks for the confirmation from one who knows. We veterans of Le Compte ownership need to stick together!

Hi John,

On the topic of making do, this is a story worth following:

https://www.sailingtotem.com/2019/09/shipyard-list-refit-for-the-south-pacific.html

* A family of 5 who completed a circumnavigation over the course of seven years while raising a young family on board and spending very little money.

* A well designed boat, but one built in Taiwan during an era when boats from that country were not known for quality.

* 70,000 miles on the standing rigging before the money to replace it finally became available.

* 40,000 miles from a bargain basement mainsail before UV finally sent it to a deserving dumpster.

* And a multi-year circumnavigation with a bottom that was sopping wet, having been peeled by the first owner and then covered up with bottom paint over raw fiberglass!

The bottom line: Money is no substitute for determination (and a strong helping of luck!)

Hi Richard,

Yes, that family has done great helped a lot by a fundamentally good boat. (Rod Stephens himself supervised the build and fit out of the early boats, which does not hurt!). That said, I agree, luck was a big part of it. For example I really don’t think going to sea with old standing rigging is a good idea since someone can get killed in a dismasting.

Hi John

Some time ago you coined a list of the important things– keeping the water out and the keel pointed down — after which everything else is secondary. The wisdom of that list has not changed!

Did I ever tell the story about sitting around in the salon of David Lewis’ schooner before it left for the Russian high Arctic, listening to he and his old mates tell yarns? His adventures were a perfect example of how it is better to be lucky than smart!

Hi Richard

I get what you are saying but I struggle to to accept a Sparkman and Stephens 47 as a poor man’s pathway to the blue water dream. For the same money they could have bought a well found smaller boat. There is no way I am taking my eleven year old daughter to sea with 70,000 miles old stainless rigging. Maybe mild but not stainless. It’s not the heavy loads on the windward rigging in challenging conditions it’s the flopping around on the leeward rigging that incrementally builds into a serious risk factor.

These people have rolled the dice and got lucky. My father was a gambler. He broke the bank at Monte Carlo and then at Cannes in the same night. I don’t believe I could do that.

Hi Mark;

I never suggested that a used Stephens 47 is a poor man’s pathway to the blue water dream. And I’d be the last to suggest that the age and condition of the standing rigging should be far down the list of priorities. In his defense, Jamie is an experienced sailmaker, and I’m sure he spent far more time going over the rig with a magnifying glass than the average sailor. (Not that that level of care uncovers every problem).

Bear in mind that this was a family of five with small children being home schooled. I question the idea that ” a well-found smaller boat” would have been sufficient to circumnavigate and live aboard while raising a family, or for that matter that smaller would have necessarily been cheaper. * What do you have in mind? A used Valiant 42for 250k, or perhaps a new Pacific Seacraft 37 for 450k?

* see the examples I listed in a previous post, starting with a 44′ boat for 75k. Private owner’s cabin, great sea berths, longer waterline than a Swan 48. Well known to me, built to at least Swan quality and equipped to leave immediately on a circumnavigation.

Hi Richard,

Yes, the list is in the article above and includes “keep the mast up”.

And I agree on luck, that said I’m more of a John Vigor black box thinker: http://johnvigor.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-black-box-theory.html

Wow. Off topic but I was not aware that Rod Stephens supervised the early boats. We have a 1982 sistership to Totem that has looked after us well after some 35,000nm so far. Thanks for that tidbit of info.

Lots of great points as always but I have to add that perhaps the only thing worse than heading out cruising with a boat that is not ready and trying to do the refit on the go is doing all of that after selling all of your worldly possessions and moving onto a boat with two small children and trying to go cruising. We did that as far as Mexico before just stopping and doing a refit on the boat (while living onboard and having another child). Seven years later we are still out cruising – mostly in the South Pacific and Micronesia but now Alaska – but what a dumb way to start !

Thanks for all your work on this website.

Cheers,

Max

SV Fluenta

Hi Max,

Yes, I think that once you actually move aboard, it’s better if the big stuff you intend to do is done. That said, I bet you did a better refit after your cruise to Mexico than you would have without the experience.

As to Rod Stephens and the Stevens 47. I raced against the first boat in Antique Race Week back in the day. Rod was aboard making sure everything was right…we did not win.

We are talking about doing another lap in a few years after pausing a bit in Victoria so I have been keeping a “next lap” list on my master maintenance/logistics spreadsheet as lots of lessons learned on where we will invest our blood, sweat and tears (and money) next time.

I have learned through experience that if the sailmaker is on the boat you are competing against you will lose. I suspect that racing against a boat with the designer onboard is even worse !

Cheers,

Max

SV-Fluenta.blogspot.ca

Sparkman and Stevens designed the Stevens 47; Bill Stevens was the moving force behind building, fit out and selling them. They were named for (and by) Bill Stevens hence the spelling of the name. The Stevens 47 was built by Queen Long in Taiwan then shipped to the USA for final fit out (rig, sails and electronics). About half the production run of 56 were sailed down to the Caribbean and placed in the Stevens Yachts charter fleet. The remainder were sold for private use within the USA.

The factory in Kaoshung was purpose built by Queen Long, but as they had never previously built a yacht, Bill Stevens hired a full time quality control person to supervise their building. The first in this position was Quentin Van der Merwe (I think I have his surname correct, but it was nearly 40 years ago and my memory may be faulty), who left when hull 13 was nearly complete. I took over and supervised hulls 14 to about 20 or 22. Quentin returned for a short time and was replaced by Jeff Fisher, who stayed for the rest of the production run.

All technical questions were directed by a clunky telex to S&S, who had an engineer assigned to the project. Anything that impinged on accommodation and/or their attractiveness in a boat show went to Bill Stevens. The level of supervision was very high and detailed, down to the level of collecting the plugs cut from the hulls for skin fittings, labelling them and sending them off to New York to be checked for thickness, glass/resin ratio and so on. As John says, Rod Stevens took a close interest in these boats, which made it easier for whoever was doing the QC to keep Bill Stevens’ wilder fancies on topics like deck gear under control.

At that time no other yacht-building yard in Taiwan (and probably anywhere else in the world) had such a high level of independent quality control. The final fit out in Maryland was to a high standard and, being close to S&S head office, was often checked by Rod Stephens. The result was a vessel that was well designed, well built and well fitted out.

Later I worked for Stevens Yachts in St Lucia where, among other things, I ran the Stevens 47 bareboat fleet. I have fond memories of them. They were very good boats then and the ones I have seen recently have held up extremely well.

Hi Trevor,

What a fascinating story, thanks for sharing it. Have you ever thought about an autobiography? I keep finding (by chance) snippets about your past and would be fascinated, as would others I’m sure, by reading the whole story.

Nice article. l love this site for its quality information but am intimidated sometimes because my offshore experience could fairly be said to fall into the “half-assed” category. I bought a Seabird yawl (26′, fir-on-fir, galvanized fasteners) and between ’77 and ’81 made fifteen offshore passages in the Pacific with no particular incident. I would like to suggest that, if the half-assed option is chosen, then a smaller yacht can add value to the enterprise. Thirteen of the fifteen passages were completed after the engine had died. The yacht’s compact size and the yawl rig helped make this work. And when the maintenance was required (and it was required) it was easier to manage.

Hi Charles,

That’s a very good point that it’s much easier to deal with gear, particularly the engine, that’s not reliable on a smaller boat.

I have owned Vaporware, a 1982 Yamaha 33 for six years. I used John Neal’s services to help find the right boat for me after attending one of his offshore cruising seminars. I was not looking for a boat to cross oceans, but I wanted one that could handle anything the sea could throw at it. The story at https://www.seabreeze.com.au/News/Sailing/Trial-by-Tasman-a-delivery-tale_1943824.aspx helped persuade me that the Yamaha would do the job.

Most of my sailing is on the Columbia River in Portland, Oregon. We race almost every week year around and have done some cruising and plan to do more as the refit progresses. Cruising around here consists of going to the mouth of the Columbia, about 110 miles from here, and turning right to go to the Puget Sound, Canada and Alaska or turning left to head for points South and West. As the Columbia River Bar is known as the Graveyard of the Pacific and the Pacific off the Oregon and Washington coast has been known for its weather since Captain Cook named a point on the Oregon Coast Cape Foul Weather, I don’t want a “Coastal Cruiser” to go up or down the coast. Vaporware might be a little less comfortable that a larger boat, but with proper preparation, I would not be afraid to take her cruising almost anywhere.

We live in a floating home at the Rose City Yacht Club. RCYC as the birthplace of Cascade Yachts and one of the founders of Cascade, Wade Cornwell, was a member here from 1948 until he died at 104 last year. He was active in club events until a few months before he died.

We have friends who left for several years of cruising in the Cascade 36 they spent many years completely rebuilding. Their shakedown cruise consisted of a circumnavigation of Vancouver Island. There are a lot of Cascades in various conditions at the club. Most of them are regularly used for cruising and there are several Cascade 36 boats which regularly race on the river. There are two Yamaha 33’s that race as well as a lot of other boats ranging from Ranger 20’s and Cal 20’s to some pretty large boats.

I know the Yamaha and Cascade are at the lower end of John Neal’s list, but I wanted a boat I could afford, one that was on the West Coast, preferably in the Northwest. I bought my Yamaha in Friday Harbor in the San Juan Islands of Washington which is also John Neal’s home port. We brought it down the coast to Portland and I have been using it and refitting it ever since. I seriously considered a Cascade 36 which was located in Coos Bay, Oregon, but I thought the price was too high. About a month after I bought Vaporware, the owner of the Cascade offered it to me at a price I would have jumped at, but it was too late. I have not regretting getting the Yamaha.

I think your advice is spot on. Get a boat, use it as much as you can and enjoy life. I am 67 years old and retired, but I expect to be sailing Vaporware for at least another 15 years.

Rick Samuels

Hi Rick,

Thanks for an encouraging report. Love the name of the boat!

Hi Richard

Nice account of your experiences with your Yamaha 33. I consulted with a client on the build of a custom 46 built in steel by a BC company called Amazon. It and the boats built by Waterline are two steel boats I would choose over almost any high end Swan or Oyster.

Before having the Amazon built, the owners sailed their Yamaha 33 from Puget Sound to New Zealand—-.

HaHa, we are doing just that atm! We are on the hard for the 2nd time in 4 months due to an issue with a bridle & a skeg. WE have spent our 20% of purchase price on adding new gear & fixing old & failing to the point that we have a very comfortable & reliable RL34. However, now that we have decided after our maiden 700+ NM journey north along the Qld coast to join the ranks of the full-time cruisers, we have in fact decided to “buy a bigger boat”. therefore, really appreciated your knowledge , wisdom & experience you are sharing with this old salty.

Hi Peter,

Glad our stuff is useful. Changing boats is a lot of work but on the other hand I think that testing out the life style on a smaller boat makes a lot of sense.

Hi everyone! Chris Steingraber of SV Humsafar (Tartan 34C) Barnegat Bay, NJ here.

I have to say that this chapter really resonated with me.

I don’t know why I love sailing so much but I just do. No one in my family sailed. But I found myself learning on my own on a prindle 16 both learning on the water and in books and videos and other online content. I always wanted to get more friends and family to come out with me when possible and be able to be dry and upgrade to a “real” sailboat that had a slip as it seamed more practical than trailering and raising a mast etc at the expense of some costs such as the slip but people warned me left and right even sailors I’d meet tell me it costs a fortune as I’d ask questions while they polished their propeller or do other bottom work. But I was determined. I basically wanted to get the biggest boat I could for cheap since I knew a 34 footer would be better to do longer trips than something smaller and I wouldn’t out grow it as fast and maybe it could be kept for a long time.

Getting a great deal requires lots of research and knowledge and being able to make a quick decision too. I found a Tartan 34C with a salty exterior but the engine would start and the interior looked great. Those two things are big requirements for me because getting something ok to work great and some polishing up and refitting is ok but redoing interior or buying a new motor was not ok for me. So that $7000 expired listing boat that I found on craigslist, I bought it for $3500 in a rainstorm in the middle of the winter. there was a boat that was over 30′ with nice interior, solid fiberglass hull, classic look, great name to it, and it started. The main was ripped in half but I taped it. I later bought eBay sail or two and learned to stictch on slides myself to make another sail work. Got a yankee jib (no roller here- hank on) and I strapped a new poly fuel tank, water separator and lines to replace the gummed up tank inside and a new carburetor and plugs and I had it running. Once I realized it couldn’t fight a current for anything while out with a cousin and uncle and what did we do instead of continuing in a bad situation we pulled to a side out of the current dropped the crappy included anchor pulled out my phone and youtube and learned how to adjust the transmission as it was slipping while we waited for the current to change. I learned little by little but being eager to learn ahead of time too is what made me have more confidence, and intuition as to control what risks to take and which ones not to combine multiple risks.

I added a big Mantus with rode only and that is dropped from the back with rode pre set running to front chock inside to rail outside of lifelines and back to cockpit where the winch can manage it to get it back in and using the motion of the boat to make it easier. I have an iPad Pro 12″ with inavx and Navionics and a handheld radio. no depth transducer or anything other than a compass and it works. I watch my map and depths, I got some Andersen winches off a salvage boat, I had to drive 5 hrs to get them but now I can single hand so easily with self tailing winches and the Lewmar clutch box and pulleys I added to run halyards aft to the cockpit. Tiller tamer was important too. Now a couple years in I feel so happy that it’s easier and easier and I can take the boat out alone and raise and lower the sails, and manage in and out of my super narrow slip well. Basically I just want to comment that this was very encouraging for me to read and I hope my comment further encourages people to pursue their goals of freedom and that it’s more within reach than most think. If you’re careful and smart and do it right don’t buy any random boat but find the perfect one in the big pile and you do have a chance. just put the odds in your favor by learning a lot and doing a lot. I don’t know if my boat is junk or not good for ocean crossings as to todays standards and all the other boats. I don’t know if it’s one of the good old ones for that. But my Tartan 34C is only growing on me more and more and I’m appreciation more virtues it has that I didn’t know as time goes on like all it’s handholds and you can’t fly too far in it.

If anyone’s in the area in NJ and needs crew to get on open water or want’s to crew on my boat nearby I’m looking forward to meeting more good people to learn from and share this experience with.

Chris Steingraber

SV Humsafar – Tartan 34C

908.397.3423

Hi Chris,

Great and encouraging story. out of interest, do you have any idea of the total amount you have spent to date. Does not sound like more that $7,000 or so, which is very cool, and it sounds like you are having a blast.

Thanks John,

I don’t know what I spent total but some main items I added incase anyone finds it of interest:

New 22gal poly tank and lines (strapped in outside at first then put under cockpit with new filler with it strapped down) couple hundred

Mantus 45lb with rated rode $750 total

Ebay main and slides and webbing from sailright $500

Yankee hank on jib off ebay to learn and single hand easy and see better and for higher winds later $300

Harborfreight solar kit ($200) goes on sale for $160 at times

New engine parts $750 about

Portapotti (boat had no holding tank just through hull head so had to go) $200

Water pressure pump ($150 maybe) new lines and faucets that hold pressure next with shower extension for cockpit shower from galley faucet possible)

New sheets and halyards (when on sale for blackfriday from west marine) $500 not sure

Walmart fenders (bigger ones) that are tightly strapped to my slip pilings so they cant move around piling. (6 or 8 pilings in a very narrow slip)

New docklines

Two andersen 52st winches and one andersen 40st winch all three $1500 from a salvage boat 5 hrs away (much easier to single hand now)

Propane stove from wallmart and heater buddy too.

Westmarine vhf radio with gps and dsc $250

iPad Pro 12” with GPS (and cell antena) with iNavx and Navionics and windy with waterproof housing wih annoying screen protector cut out and siliconed it to still seal $1000 financed through AT&T (needs a hood to help low brightness)

New deep cycle battery $200

Harness/inflatable west marine life vests on black friday sale.

Big orange round fender as anchor marker

2200 lumen walmart spotlight (rechargeable)

Walmart all round rechargeable lantern (for anchoring hoist it on halyard) (my stern light and mast lights and anchor lights dont work yet.

Oh and new transmission push-pull cable heavy duty with 4” travel from mcmaster-carr for shifting transmission.

No bimini yet, no dodger, no shore power connections (bought solar instead) but it’s great and i have two mains now and a yankey, two diff genoa’s and a spinnaker yet to try (bote has a whisker pole too.

And i cut a fishhook pole wooden handle into three along with old mainsheet to make a boarding ladder for climbing back on when going for a swim or to scrape a few barnacles off the rim. It works great. Next up is tung brightwork will get sanding, tung oil, then spar varnish finish maybe for more uv protection.

I have some pics on my instagram @chrissteingraber

Hi Chris,

One thought that just struck me while reading your comment. A household gas stove and heater from Walmart, particularly combined with the gasoline engine, that many of these old boats have, could very easily kill you. At the very least you should be installing a propane/gas sniffer.

More here:https://www.morganscloud.com/2015/08/16/ten-ways-to-make-propane-safer/

Hi Chris,

I too have a bit of an old boat that I’ve been fixing up. I replaced all my lights with LEDs and fixed the wiring for them earlier this year for pretty cheap. It took a bit of figuring to be sure of USCG regs, but here’s what I bought:

https://smile.amazon.com/gp/product/B004XAD5DW/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1

https://smile.amazon.com/gp/product/B00B8593GS/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o03_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1

https://smile.amazon.com/gp/product/B001B012D2/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o04_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1

YMMV, but they fit in the original holes on my boat (Catalina 27). Also, be careful to not cheap out on the actual wires. Marine cable is tinned all the way down it’s length which will last 2-10x as long as normal untinned copper near the salt.

-James

Hi James,

Have you tested these bulbs for RF radiation as per the US Coastguard bulletin? For this reason, and also colour accuracy I’m always nervous about these LED bulbs, rather than a purpose built LED nav light.

John,

I have not done the exact test the USCG recommends, and for completeness I probably will this weekend, but I’m not very worried about RF/EMI in this specific case. I think it’s worth considering at least, the causes of the concern, and when they are likely to occur. The problem of elevated noise on the antenna wire, and thus decreased signal to noise ratio (and degraded performance) of a radio, will be due to spurious RF emissions. LEDs operate at a voltage much lower (1-3VDC per die) than typical boat power systems (12-24VDC). There are essentially 2 means of regulating the current through the LEDs (thus lowering the voltage across the LED), Switching power supplies and Linear systems.

Switching power supplies are more costly but generally much more efficeint. They get this efficiency by turning the current on and off through the LED very fast (typically 100kHz to 10MHz), which I’m sure you know is exactly what makes RF. Since there are wires carrying that current (which is alternating from on to off), they will end up being little antennas which can induce a signal on your VHF/AIS/SSB antenna and thus degrading your SNR at the reciever. Careful shielding and design of the power supply is needed to keep these to a minimum. Testing is expensive and generally only done for safety, not performance next to a radio reciever, so it’s one place where cost management can make this a problem for the end user.

The second way to control the current through the LEDs, and due to it’s cheapness, the far more common option, is to use a resistor or linear regulator. This is much less efficeint, since you have to burn the power to get the voltage down to LED levels in the resistor or regulator, but it’s only 1 component on the board. However, using a resistor (or linear regulator) won’t produce any RF/EMI since the current will be (essentially) constant.

Ironically this means that a cheap replacement bulb from china with just a bunch of LEDs and a resistor actually has a *Much Lower* chance of producing unwanted interference on the radio. It’s the more (electrically) efficeint switching power supplies that are the culprit. The kind of thing you’ll find in a fancy complete replacement unit with no interchangeable bulbs, since the power supply is matched to the exact LEDs they chose. That said, a *well designed* sealed unit built with LEDs and including an efficeint switching power supply is a very attractive option, especially since the lens optics can be optomized for the LED emission pattern, which is another win. If you are just replacing lamps though, you can get 80% of the benefit (drastic current reduction and/or increased brightness) without much cost or labor.

Your points about color temperature are spot on however. I just don’t care that much what CCT of the Anchor light is ;). I do recommend making sure to match all the ones on the interior cabin and finding the color temperature you like, since there’s so many options out there.

Hi James,

I’m pretty sure I’m right in saying that cheap LED bulbs have a terrible RF track record and that’s what spurred the coast guard warning. Also colour temperature is not a matter of taste on nav lights, it’s a safety issue since if it’s wrong it can result in misidentification by another vessel. If memory serves there was a warning memo from USCG about that too. Do keep in mind that if you have an accident all of these things will affect liability. Do what you wish, but I would not pick this as an area to save money by using no name products that are not in any way certified and where the manufacture is, on a practical bases, anonymous.

Hi John,

I’m a new subscriber to your site, and I have to say that the breadth of information is impressive!

My wife and I live in Toronto, Canada, and we are a few years from retirement. I was first introduced to sailing some 25 years ago on my dad’s sailboat, a 27′ Jeanneau Fantasia that he kept on Lake Champlain in Vermont state. We have since chartered sailboats several times in the BVIs, Grenadines and Bahamas, and we have taken our ASA 101, 103 and 104 in recent years. My wife and I are now planning to purchase a sailboat in the 40’-44’ range. We are looking for a blue water cruiser with an aluminium hull and lifting keel. As a result, we’re considering French or UK brands such as Ovni, Allures, or Southerly on the second hand market and having it moved to North America. We plan on sailing initially in North America (Great Lakes, US East Coast, Chesapeake, IWC, Bahamas and Caribbean) for the next 4-6 years before crossing the Atlantic with her to spend another 3-5 years cruising the Med and beyond.

Since we’ve never owned a sailboat before, I’m trying to understand how difficult the process of converting the electrical system is from EU to North American standards? Given our sailing program and the fact that we most likely sell our boat in Europe in 10-12 years from now (the demand for this type of blue water cruiser is greater over there), would you recommend another strategy to handle the electricity on board when purchasing a used European sailboat.

Thanks in advance for any help you can offer, and stay safe!

Dominique

Dominique,

That really depends on how complex the boat’s AC wiring is.

On a new build or a significant re-fit, I would normally specify a very minimal AC system. The boat’s systems would all be run from the DC main bus, with inverters to handle the loads that must be AC. The shorepower system would only be connected to the battery chargers and to a handful of service outlets for use during maintenance when the DC system is shut down. Such a setup doesn’t need many changes for Euro vs. NA power; the chargers just sense the voltage and self-adapt.

On a boat that’s heavily shorepower dependent, it can be much more painful. The wiring itself and the main panel might, if you’re lucky, be OK on either system. Changing out CEE 7/7 receptacles for NEMA 5-15 is not terribly difficult. But air conditioners, fridge compressors, dive compressors, transfer pumps, etc. designed for 240 V 50 Hz don’t always have the winding connections available to work at 120 V 60 Hz; you’re re-wiring all of them at best, or scrapping and replacing them at worst. You can’t rely on the availability of 120/240 V split-phase power or 120/208 V three-phase power on the North American side to get Euro-compatible voltages; that’s possible in a house or commercial building, but very rare in marinas.

(That sounds like a Colin Speedie question, to be honest; I’m pretty sure he’s helped people through the Euro-to-American transition a few times.)

Hi Dominique,

First off, I would not worry about doing a conversion. There are ways to manage this quite well without a project of that magnitude. We made two cruises to Europe, with a total of over three years there, on a North American wired boat without significant issues or conversion.

The nuts and bolts of it are way beyond what I can do in in a comment, but the fundamental is that we used the taps on our isolation transformer—should be installed on all metal boats, although often not on some European boats—to convert voltage. That then leaves frequency to deal with. The good news is that most modern battery chargers are frequency agile, so for gear that will not run on the destination country frequency the best bet is to charge the batteries from shore power and then use a good quality sign wave inverter—present on most boats these days—to provide the correct power and frequency. If you end up, as we did after a few years, with different gear requiring both frequencies then you may, as we did, end up with two inverters, one for each.

Do you really NEED a cruise-ready boat? I thought I was ready to go, but illness in a parent and Covid shutdowns resulted in me having 3 full years to discover and work out the weaknesses in my boat (and the skipper). H/A option has worked out well in the end!

Hi Martin,

As I write in the post, that depends on the person, time of life, and on it goes. Lots of different ways to get out there.

John,

I can’t believe I’m 4 years into a refit and just stumbling on your site now. I started my “half-assed” ownership with a “free” Tartan 37 (two most expensive words in the English language – free boat). I figured I’d just make the boat “sailable” and a bit more comfortable, then go cruising. That’s what I did the first season. Relentlessly, I worked on the boat for 2 months in the water then cruised it for a few weeks in the Chesapeake Bay. It was fun, safe, and rewarding, but it also wet my appetite which is not a good thing for the obsessive compulsive. I dug in further the next year, spent hundreds (maybe more) hours of hard work, thousands of dollars, cruised extensively in the bay and took the boat to New England for a few months in the summer. What followed for the next two seasons was more of the same – massive projects, 10’s of thousands spent, thousands of hours, etc to do it again but with more comfort, safety, performance, etc. It’s been all-consuming. I’ve had incredible experiences with friends and my wife. Now I have a boat that is immensely capable and I’ve learned a ton. I’m 54 and have sailed my whole life – from extensive big boat racing, one-designs, and 25 years of competitive international dinghy racing. The last 4 years of cruising has been very difficult in preparation but immensely rewarding. But, I have a big problem that I can’t reasonably solve myself this time for the lack of time and indoor space – all the hard sailing I’ve done has exacerbated a problem I’ve known about but have not been able to address in total – a wet deck. Now I’m at an inflection point. Do I pay a professional $30K or more to fix it (not even counting for proper cosmetics), or do I take it in the shorts in a sale so I can get the boat that brings me into the next phase of cruising? I’m not sure what the answer is son I’m pursuing a parallel path by simultaneously assessing both options. It sounds as if your Fastnet 45 experience was similar. Do you have any misgivings considering how much you’ve gained through the process of refitting/rebuilding that boat? Thanks.

Hi Jessie,

I can’t tell you what to do, but I know for sure I should have bailed on the Fastnet way earlier than I did. The key to making this decision is to ask ourselves constantly if the boat we have will meet our cruising needs long term, or is it a starter boat to learn on? If the latter, we should get out as soon as we have learned enough not to make another mistake on the next acquisition. The longer we hold on after that point, the more money and time we sink into the wrong boat.

Thanks for this comment. It really helped.

Hi Jesse,

Glad to help, it’s a difficult and not-fun call to make.