I suspect that this post is not going to make me popular, but I’m seething about what’s happening with these rallies and offshore voyaging in general, so here goes—brace yourselves.

What the heck is going on here? As I understand it, 116 boats were registered in the Salty Dawg Rally and at least five of them required US Coast Guard assistance.

Regardless of the exact details, this is on top of several tragedies in other rallies in recent years and countless rescue missions for the US Coast Guard—well done the SAR crews—and commercial ships.

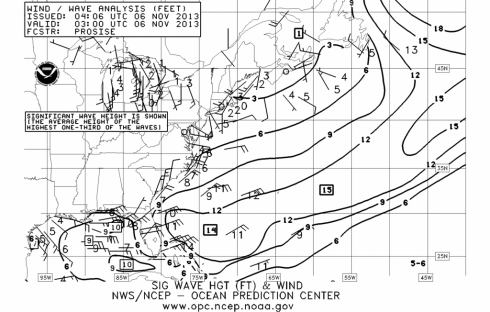

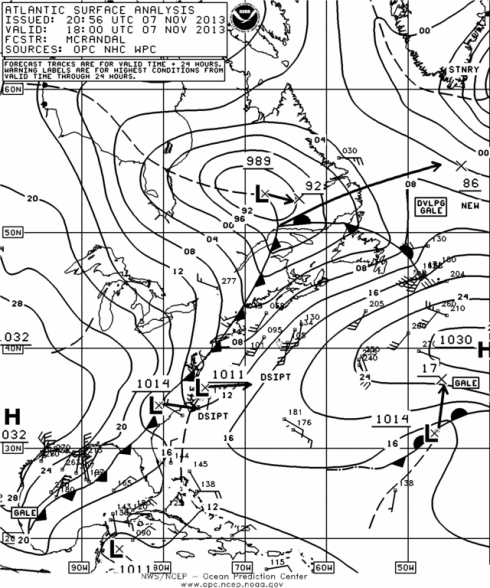

Now I don’t know exactly what the weather was like out there in early November when the problems occurred, and there is no question that the area off Hatteras can be a nasty place. But as far as I can see, having looked at the sea state and surface analysis for those days, the highest significant wave height was 3 meters (10-feet). See chart above. Which would indicate that it blew no harder than sustained—I’m not talking gusts or squalls here—near-gale Force 7 (28-33 knots), and that not for long (the chart of the 10th shows that it was all over by then).

Yes, that’s uncomfortable, and could even be dangerous in the Gulf Stream when blowing against the current. But no one should have entered the Stream if they were not sure they could cross before the weather got gnarly, so that excuse goes away.

My point is that this was at worst a near-gale at sea, more likely just a pretty normal frontal passage—not the Queens Birthday Storm or the 79 Fastnet—but nearly 5% of the fleet needed assistance. I think this is simply not good enough and reflects badly on all of us in the offshore voyaging community.

And it’s not just this year. In recent years the annual fall migration has turned into some kind of demolition derby, for crying out loud. Sure, bad stuff that requires assistance can happen to any of us, including me, but this is getting silly.

OK, enough ranting about what’s wrong, what are the causes and what can we do about it?

Avoid The Fall Rallies

I really encourage everyone, and particularly those with less ocean experience, to stay away from these rallies in the fall. In my opinion, they confer an illusion of safety in numbers, that encourages the unprepared and inexperienced to go to sea when they shouldn’t, combined with a herding sense of urgency to depart. Yes, I know the Salty Dawg didn’t have a set departure date, but the pressure to go with friends and other boats is still there.

It’s a Tough Passage

Rallies may have a place in the trade wind belt at the right time of year, but a fall crossing from the US East Coast to Bermuda and/or the Caribbean is one of the potentially toughest voyages you can do.

This I know. In 40 years of voyaging I took my worst ever caning (worse than anything I have encountered in the high latitudes) off Cape Hatteras on my way home to Bermuda one November.

The point is that, in my view, counter-intuitively, the tougher the passage the less desirable joining a rally is. And don’t even get me started on the dangers of rallies through the NW Passage!

And Getting Tougher

By the way, going south from the North American East Coast was always a tough passage, but I really think that climate change has made it harder still, to the point that I would now not count on a passage to Bermuda in the fall.

I might set up to go from say Newport or the Chesapeake (safer than Newport), but I would assume at least a 30% chance of waving it off completely—not something I would have said 15 years ago.

Basic Seamanship

I have ranted about this before but, just by looking at boats getting ready to go offshore, I can see that their owners are not putting proper effort into basic seamanship and preparation:

- Boats festooned with all kinds of junk that will cause problems at sea in any kind of heavy weather. Excessive numbers and/or poorly mounted solar panels, jerry cans of fuel, and large RIB dinghies, are the worst offenders.

- No provision made for shortening sail easily in heavy weather.

- No provision made for easy setting of a storm staysail and storm trysail.

- No backup for an electronic autopilot.

- No proper sea berths to make sure that the off watch can get adequate rest.

- No ready-to-go provision to go passive, without having to steer, by heaving-to or streaming a drogue.

Bottom line, if a boat is not set up properly for offshore voyaging and the crew have not practiced all of the evolutions mentioned above, offshore, at night, in over 25 knots of wind, the boat does not belong at sea, and certainly not in the fall.

Weather Routing Delusions

I have saved what I think is the biggest reason for this sorry state of affairs for last. Back 40 years ago, when I first started ocean passaging, we were subjected to at least one gale, and maybe worse, on at least half the passages I went on. The reason was simple. We set a date to go, and when that day came, we went. That was just the way it was. Weather forecasts were pretty useless past 36 hours then, so why try to pick a window? We went to sea and dealt with what came.

The result of these frequent heavy weather experiences was that we knew better than to make the basic errors detailed above. That knowledge was just embedded in the sport of offshore sailing.

But about 20 years ago, much better weather forecasting became available and cruisers started buying routing packages from the professionals and listening to gifted and dedicated amateurs like Herb, of South Bound II fame. And gradually, over time, a very dangerous delusion set in.

A whole generation of offshore sailors, and aspiring ones, have got the idea, aided and abetted by the yachting press, the routers, and perhaps several easy passages, that if they just have a good enough forecaster on their side and wait long enough for a window, and blindly do exactly what the router tells them, they can go voyaging and never face a gale at sea. And they set their boats and themselves up on that assumption. Well, that’s…let me see if I can put this gently…bullshit.

Even today, forecasts are only reliable out about 72 hours, and that goes double for the fall in the North Atlantic. So any boat and crew that are planning on participating in the fall migration should be comfortable with the fact that they may be subjected to gale force winds at some point and that there’s a very real chance that they will experience a full-on storm at sea, and prepare accordingly. A boat and crew that is not confident in their ability, and willingness, to deal with that, should not go to sea, it’s that simple.

That’s OK

By the way, if you make the decision to limit your cruising to short coastal passages so that you don’t have to make the commitment in boat preparation and crew training to be safe on a multi-day offshore voyage, that’s absolutely fine and I won’t think any the less of you, and neither should anyone else.

In fact, in recent years, even though we maintain Morgan’s Cloud in full ocean crossing readiness and do still make challenging voyages, Phyllis and I have cut back on the number of multi-day offshore passages we do, in part because, as we get older, our willingness to subject ourselves to a gale at sea has diminished.

Bottom line, know your own and your boat’s limitations and sail within them.

John, I don’t often comment but I read almost all of your postings. Your rant was a good wake up for all of us, wherever we sail, and I found myself mentally ticking off Let’s Go!’s preparedness against your check list as I prepare for the next challenge. I found myself getting uncomfortable I am afraid. Thanks for the rant.

Jim

Hi Jim,

In almost every case where things have not gone well on “Morgan’s Cloud” it has been as a result of hubris on my part—we all have to guard against it. Given you and your boat’s track record, your openness to continually examining your preparedness is the mark of a true seaman.

Very well spoken John! It is good that a very experienced off-shore racing and cruising captain like you says this. Safety should always be above other priorities. I am now sailing north in Danish waters going home to Norway for Christmas. I want very much to get home, but there is a very bad storm coming. I have found a safe harbor and will wait out the storm. That is always the best way to do it. But please show us some of your nice photos and not those ugly diagrams of bad weather.

Best regards Svein

Hi Svein

Lets hope you came home in one piece. Some harbours in Danmark did not fare too well in that particular storm.

Hi Enno

The storm Bodil became very bad. As you know some harbors are gone with the wind. I am fine and had no problems. Some long lines against the main directions of the storm did it. I still plan to celebrate Christmas with family and good friends in Lofoten. But it is storm season and one must be careful.

Sail safe, Svein, it’s a long way to Lofoten. All the best for a good passage.

Thanks a lot John, but I will not go all that way in my slow sailboat. I will go aboard MS Vesterålen in Bergen the 16. of December. MS Vesterålen has 2 x 3000 hp Rolls-Royce diesels and belongs to Hurtigruten. We shall cruise north to North Cape, then east to the Russian border and back south to Lofoten. We stop in Lofoten two days (24 and 25) to celebrate Christmas. A plan like this has something in common with a rally: Because you follow a plan you might have to fight a storm you otherwise would have avoided. At present moment there are two bad storms in this waters. But I am very optimistic; Vesterålen is a good ship commanded by the best and most experienced captain of all the Hurtigruten captains, Mr. Klodiussen. Captain Klodiusssen has done this trip for 30 years and never had any accidents. Vesterålen has the best food of all the Hurtigruten ships. I will most likely come home heavier than I am to day.

Dear John,

You find no disagreement from me in any of your positions: quite the contrary. And with regard to the self description of ranting: I do not see it: rather you take a position that is un (certainly under)-articulated in the often self-serving worlds of boat building, marine media and rally organizers.

I agree absolutely: the rally’s promise of a safety net is an illusion: one teaspoon of salt water in the SAT phone or SSB or its various connections and the vessel/crew is completely on their own and they should prepare for this possibility. Rallies are first and foremost (in practice) a social event and should in no way be considered a substitute for complete skipper responsibility for boat and crew safety. Furthermore, acceptance of a skipper and the vessel on a rally should not be understood, either by the skipper or, more importantly, the crew, as evidence that the skipper or boat is ready for the intended passage.

I have written about this issue in the past and thought it interesting to develop a realistic experiential list of requirements (beyond the writing of a check). I tried engaging a few in this endeavor, but got zilch response. My ideas went as follows: for an ocean passage greater than a few days, 20 of 25 skills/experiences must be under the skipper’s belt. These experiences could include: 1. Heaving to in near gale or above, 2. Bleeding your engine, 3. Three nights at sea, 4. A level of RYA proficiency, 5. Actual MOB practice in your vessel, 6. Setting reefs in a squall, etc. You get the idea. For less ambitious rallies, less demanding experiences would be required.

Rallies hold the promise of delivering much of what the cruising community has to offer that is wonderful: interesting people doing adventurous things and learning from each other. It is nice to have company at times. Rallies also hold potential of embodying/enabling much that is problematic in our community: the influence of money, skipper’s wishes for shortcuts, media’s investment in the rosy picture. It is the latter picture that prevails too often in my observation.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi John,

I just added a link to your rant on my blog on the same subject. http://aleriasadventures.blogspot.ie/2013/11/rallies_25.html

We’ve also been talking about climate change and how that is affecting long distance cruising. I’d love to hear a sailing climatologist’s perspective on that.

Cheers,

Daria

Hi Daria,

Just read your piece. Great stuff and a different, but just as valid, look at the same issues.

I would highly recommend Daria’s article to all.

Your comments ring true to this veteran of nothing more challenging than a 2 week coastal cruise, but some 50 years of reading and dreaming. I have one additional observation: It seems to me these rallies not only result in a false illusion of safety in numbers, they are much less safe in that with more boats out there, more get in trouble, overloading (as this one did) the rescue forces.

I recall US production boatbuilding being snuffed out in the mid-eighties by the S & L crises and Asian competition. The turnaround seems to involve a rampant consumerism generated by rallies and the Big Cat that came to town to re-invigorate the charter scene. Bubba is building Beneteaus and Jerry Jim is putting together Jeanneaus.

Squirrels crossing the road…some make it…some don’t.

Tom Chapman

SV Tatoosh

Astoria

Hi John,

Good post, but too general. I’m the organizer for the Caribbean 1500, and a professional sailor myself. The ‘demolition derby’ of rallies as you describe it has been limited in the past few years (since World Cruising Club started running the 1500) to the NARC and the Salty Dawgs. Don’t roll us up into that.

Your comments on preparation and weather echo exactly the framework around with the 1500 is organized. Highest safety standards, focus on preparation, and knowledge that the weather can turn lousy out there, but that you can be prepared for it. Just today I wrote a long critique of my own (to be published soon), which will clear up some of the differences between the SDR and the 1500. I look forward to publishing it. In the meantime, here’s my own brief analysis regarding the weather, which I hope will make you change your mind on rallies in general – the 1500 is different:

“It’s not, and never was about the weather. It was indeed a factor for the SDR, but it wasn’t the core of the problem.

The Carib1500 departed on a tight window, and our fleet had winds gusting to 30 knots for 3 days, with 12-foot seas – but it was from the ‘right’ direction (ie: behind them) – we took a calculated call on that window, knowing full well we’d have strong winds and heavy seas (WRI, our forecasters, acknowledged conditions were “far from ideal”).

But we took the ‘devil we knew’ with the long-term forecast of high-pressure ridging and northerly sector winds (and importantly, no frontal passages in the Gulf Stream), and people were ready for it – no surprises.

Indeed the 1500 fleet got through without any major mishaps.

While the SDR fleet experienced worse weather for sure, it was far from survival conditions (with USCG rescuers reporting winds in the 30s and 8-12′ seas), and boats going offshore ought to be prepared for and able to handle conditions even 50% worse than that. SDR organizers admitted as much themselves:

“In this case, things changed and the frontal system stalled and intensified, however, experienced sailors should be able to handle these situations.”

The main difference between the SDR and the 1500 is that we have a series of failsafes in place to mitigate the worst-case scenarios when going offshore – boats must meet a certain standard of seaworthiness (and are advised to these standards in the months leading up to the event), skippers are expected to comply with the highest in offshore safety protocols (namely ISAF’s Special Regulations, which are used as a basis for all WCC rallies regarding safety equipment), and crew and boats are expected to have undertaken a passage of at least 250-miles to shakedown the boat and the crew, and learn how best to sail with one another.

I don’t doubt that the majority of the SDR fleet were experienced and had no trouble. I have nothing against going it alone – in fact, I did so myself with my wife, sailing to Sweden from Annapolis in summer 2011 via Newfoundland and Ireland. We enjoyed a 23-day crossing to Ireland with no issues at all.

But, as Andy Chase, Master Mariner and instructor at Maine Maritime Academy so eloquently put it in an article about the sinking of the tallship Bounty, “Every voyage carries a degree of uncertainty,” Chase continues. “In everything we do, and even when we do nothing, we assume a level of risk. So we manage risk everyday. But when we are in a position where we are managing other peoples’ risk” – ie in the case of any organized offshore event like the SDR and 1500 (regardless of how ‘unorganized’ the SDR strives to appear) – “especially when we are engaging in activities that carry significantly elevated levels of risk, it pays to get more organized about it.”

Furthermore, as Chase puts it, “Experience in a vacuum doesn’t make us smarter. Experience has to be processed. It has to be considered with full disclosure.” He goes on to say that un-distilled experience often simply leads people to become “bolder.”

So how is it then that the Salty Dawgs claim to be such ‘experienced’ sailors, and yet so many seemed so vastly unprepared for undertaking such a voyage? I don’t doubt the core of that group is indeed very experienced and very knowledgeable – in fact I know some of them personally, and regard them very highly. ”

But somehow, that knowledge isn’t getting properly disseminated to the group.

Read the full Bounty article online in Woodenboat Magazine here: http://www.woodenboat.com/lessons-bounty

Hi Andy,

I’m sorry, but I can’t agree. While I particularly singled out the Salty Dawg because of what happened this year, I believe that everything I wrote in this post applies equally to all rallies, including the 1500.

The bottom line is that, in my opinion, rallies are intrinsically dangerous because they mix a financial interest of the organizer to get as many boats to sign up as possible with the natural human concept of safety in the herd, which in offshore sailing is a delusion.

I also think that rallies, together with overly controlling weather routers, have, over the years, eroded the basic decision making and risk management skills of offshore sailors by propagating the illusion that someone off the boat can be responsible for said boat’s safety.

Andy Chase’s excellent article does not say anything about rally organizers or anyone else off the boat doing risk assessment, it’s all about the crew on the boat.

Further, I believe that the single 250 mile passage requirement is totally inadequate. Such a passage that will take less than 48 hours can easily be done in totally benign weather and will do nothing but increase the hubris of the participants. I would suggest that if you really must go on running these rallies that you adopt the CCA Newport Bermuda race experience requirements, which are much more rigorous, and that for a race that takes place at the most benign part of the year, not November.

Thanks for the wake-up call on this, John. And kudos to the USCG captains and crew.

How many old stories of ships at sea have, at some point, a chapter where there’s a whole gale blowing and green water over the decks?

Right. All of them. Surely the sea hasn’t become any more docile or forgiving in the last few decades just because we’ve built more instruments to watch and record what it’s doing.

John, no arguments here. I see the increasing resort to various SAR and CG services, however, as “multi-factorial”, if I can trot out a five-dollar term.

1) The big red button, by virtue of being available in the form of EPIRBs, satphones and so on, gets pushed earlier in the process. If you are merely sick and tired of sailing, you can be removed from an intact or lightly damaged boat. Back even 15 years, when the choice was more limited, the stakes for calling a MAYDAY were, I think, higher.

2) The arrogance borne of better forecasting, but not *perfect* forecasting, means people sail to a schedule, or assume that they can “game” conditions to take the good wind, say, without the bad seas. Without a reliable long-range outlook, one could only anticipate, as you said, “the next 36 hours”…but you had to prepare, in every sense, for Force 10 weather as a small but real possibility.

3) The paradox of better forecasting is that it means people get “jumped” more rarely by bad weather: They stay home or inshore. Consequently, they may have a high ratio of “fair-weather sea miles” without having experienced, or had to manage a boat in, really rough, blowy conditions. The prudent thing to do, within reason, is to learn how to sail your boat in bad weather by…wait for it…sailing in bad weather. It’s understandable that there’s a reluctance to risk gear and even life by seeking it out, but if you don’t know how the rigging screams past 40 knots, you might find it paralytically unnerving 400 miles offshore. Even on usually predictable Lake Ontario, I take the sloop out in 25 gusting 35 for a little green water back to the winches action, because it’s good for myself and my family to practice tacking and gybing in such conditions close to home and “outs”. But I’ve ceased to be surprised to see that we are frequently one of the few boats out on part-gale days, even though a properly reefed-down boat on a reach is a glorious thing to sail. As Matt noted, the sea isn’t more benign, and it takes some practice to deal with “moody”.

I wrote earlier in 2013 about the role I feel such services as weather routing have to the distance cruiser in the context of the rather sad end, in my view, of Herb Hilgenberg’s radio career here:

http://alchemy2009.blogspot.ca/2013/03/clash-of-weather-titans.html

While I haven’t been in a November rally in the general direction of Bermuda, I’ve crewed on a delivery while the Caribbean 1500 was going on, and in conditions rough enough for long enough to part forestays on Swan 53s (this was 2009’s 1500). It was Herb’s suggestions that kept the frying pan, so to speak, from turning into a fire, but it was our skipper’s evaluation of the entire sea situation that, in fact, got us through without more than bruises to show for a rough passage. Sorry about the length here!

Hi Marc,

You make an excellent point about the ‘big red button.’ Don Street (whose ‘Ocean Sailing Yacht’ vols. 1 & 2 are still in my opinion, the authority on outfitting for bluewater sailing, if you can get past the dated stuff) is constantly to this day huffing and puffing about properly sized manual bilge pumps on offshore yachts. He’s right, of course, but I think he misses the point – a lot of sailors today will simply hit that button and call for help long before they ever exhaust all measures of saving the boat.

But you have to stop and think how’d you’d feel in that situation before just criticizing – if there’s a tanker waiting alongside you’re sinking boat, are you going to risk your life to save it in the face of near certain rescue? The tanker’s not going to wait either – it’s usually now or never.

I think most ‘hardcore’ bluewater sailors would say they’d do everything to save the boat – and that should be the prevailing attitude – but under real circumstances it might be a tough call. Something interesting to ponder.

But I think the attitude about getting off immediately is still one that needs to be changed, and ultimately, I think Street – and you – are right.

+Andy

I certainly concur that pigheadedly “staying with the boat” is probably as poor a decision as premature button-mashing these days. But this is a decision that has to rest with the skipper and (to a lesser extent if they are less experienced) crew. I think my point is that if the modern rally or cruising skipper, having had by choice or design a easier racking up of apprentice sea miles than would have been the case for a veteran like Don Street, is basing their decision-making on their skill set and experience, they are limiting a chance to save the boat and solve the problems confronting them.

In other words, you need to take a few punches before you can bob and weave, mitigating to a degree further punches.

I am reminded of a recent RYA course I took, during which the GPS was out of sight, and the instructor frequently clapped the binnacle compass cover closed, as I was expected to steer to the wind shifts, by direct observation of landmarks and wave trains, and by the feel of the wind on my skin. It was very instructive to realize that while I criticize others for peering constantly at a plotter screen, I myself can fall under the spell of the compass card.

So if we wish to progress in sailing, and do rallies out of sight of land, Sea-Tow and even easy SAR reach, we have to self-train in methods of sailing premised on most of our navigational aids being out-of-commission. I don’t see among sailors a taste to deliberately develop such skills, or to risk discomfort and gear in middling-bad conditions in order to prep for survival conditions. The results may be seen in the increasing number of bail-outs from rallies, I think.

It’s an interesting problem, however, and I will think of Mr. Street when this winter I’m installing my Patay manual bilge pump, which I describe as “powered by motivation”, and for which I get a few sarcastic remarks. But I wouldn’t push off without it or something similar. Read too much old-guy sailing books, I guess…they get to *be* old-guy sailors by avoiding young-guy mistakes.

Hi Marc,

Your RYA example brings up another great point – the level they expect you to achieve in order to gain any qualifications is remarkable. I went through the Yachtmaster exam, and it was downright difficult – on average, I think 1/3 of the applicants fail the practical portion, and usually these are aspiring professional sailors. You’re expected to be able to navigate ‘blind’ as you mentioned, maneuver under sail around tight quarters, plan long passages for tidal streams, etc. All while using the other applicants as your crew in a team environment.

In comparison, the USCG Master Mariner exam for anything under 200 tons is a joke – just textbook stuff, no practical, and nobody truly checking your experience (which you can sign off on your own boat).

The RYA uses the rigorous types of standards we ought to be striving for in all kinds of sail training.

+Andy

Andy, I concur. I found my recent experience both informative and humbling, but mostly, I realized that many of my respected sailing colleagues would have been largely lost…well, not the older guys with salt water time.

There seems to be no comparison between the level of sea knowledge required by the RYA and anything in North America short of commercial training.

Hi Marc,

Interestingly, I do think the USCG does a better job with ‘experience’ – all you need for a Yachtmaster is 3,000 miles – one Atlantic trade wind crossing as a crewmember, and you’ve got it (plus having to do the course and the exams of course). But the USCG still measures in days – minimum 360 for Inland, 720 for Near Coastal I think. So if you’re getting your experience offshore, you’ll rack up WAY more mileage counting days than simply miles. Seems like there ought to be a better way to combine the rigors of the RYA training with the experience requirements of the USCG.

+Andy

I totally agree. I hold both a USCG license and am a RYA Yachtmaster. I’ve always felt the Yachtmaster was more valuable and harder to get.

There is a loose parallel here with the decision to eject from a disabled aircraft. Some go too soon, and some die from going too late…and others die because they are protecting people.

In each case there are a set of common factors which puts the final decision in the it depends category.

The three below most often cited in going early are (mis)assessment of the situation, panic and lack of training in the alternatives.

Factors affecting when to pull the handle/Hit the button

Fear

Fear of ridicule

Over confidence

Concern for Others (People on the ground – Rescuers)

Pride

Coordinating the crew

Assessment of the situation

Degree any of the necessary actions have ever been practiced

Violence of motion

Loss of situation awareness/disorientation

Physical injuries

Sea sickness or other illness, exposure to toxic fumes (fire)

Mental incapacitation (Concussion, etc)

Personality type (Susceptibility to panic)

…

Dear Andy,

There are many aspects of your spirited defense I might challenge, but your choice of language captures my concern. When you use the phrase “series of failsafes” to my experience you are selling an illusion. Now, I recognize that you slip in the word “mitigate” to soften that bold statement, but the thrust of your argument is that you have a mistake proof system: a better “failsafe” Carib 1500. I usually do not care when people wish to sell an illusion, after all it is clearly a huge part of our commercial world, but I do care when it adversely effects a world I care about.

Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

Thanks for the reply, and I appreciate your comments. ‘Failsafes’ may have been the wrong word – of course there are no guarantees in anything, much less a risky adventure like ocean sailing.

I’ve been put in a position as manager of the 1500 where I have an opportunity to shape the way people learn about offshore sailing, and I take that responsibility very seriously. We’re not selling any illusion – dreams of a lifetime? Yes. But we’re not promising anything.

You’re only as safe on the ocean as your knowledge, skills and most importantly your preparation make you. And that’s the point I’m trying to make here. When someone signs up for the event, open to receiving whatever knowledge they can get while they prepare themselves and their boats, we have the responsibility to SET THEM UP for success as best we can – through training courses, shakedown cruises, seminars and discussions. Once they head offshore, with or without the rally, their preparation will determine their success and their enjoyment of it, and at that point we no longer have any control over it.

So the bottom line is, I care as much about this world as you do, and I’m doing my part to help those in it come to understand it better and hopefully better prepare for the realities of it. No illusions here Dick, and had you been at the Skipper’s Weather Briefing this year, I think you would have agreed.

+Andy

Hi John

Thank you for this post!

Now I no longer feel licke a complete freak because I’m feeling a strong desire to get some real heavy weather experience.

I recently got into some force 8 gusts on the lake of Konstanz. Well, I made mistakes I really shouldn’t have, but in the ende nothing worse happend and I have to say that I don’t think I learned that much about sailing and boathandling in this 2 hours since my first sailing lesson.

Regards

Simon

Bravo John and well said. Bullshit it is. And as for a NW passage rally, stronger expletives come to mind. We can look to Everest to see where selfishness, ignorance and commercialism is taking us.

This is a good discussion! I have crewed on different boats on four 1500’s and once on the first Satly Dawg Rally. The bottom line to me is that anyone making the November voyage, either as part of a rally or on their own needs to have full awareness of what they are getting into. Rally requirements for safety equipment, boat inspections and seminars help, but it is the captain and crew’s responsibilty to ensure that they and the boat are truely ready for what lays ahead. Rallys that do not fully interact with their participants on safety requirements and inspections end up having boats participate that are not prepared. I fully believe that is a large part of what happened in this year’s SDR. If you want to participate in a rally next November, you should have started preparing earlier this year. Don’t upgrade things right before the start of the rally. have them fully working and tested and get some experience with the upgrades. How old is your rig? How many experienced crew members will you have with you? Have you sailed with your crew before the rally? As a crew member, are you comfortable with the boat and the skipper? You have to be able to work as a team and be able to deal with the issues that may occur.

I thorougly enjoy offshore sailing and will be doing a transatlantic next year. I hope also to be on the 1500 again. This year I was working with the skipper by May and we had a great passage because we were prepared and made sure that the boat was ready.

John: I agree with and learn from your comments on preparedness. But all your points argue for more experience and preparedness, not for “everyone, and particularly those with less ocean experience, to stay away from these rallies in the fall.”

The analogy to the Everest climbing experience may not be a bad one. Based on numbers alone, 1996 was no statistically worse outcome than historical. But valuable lessons were learned from that experience, and since then the climb is statistically “safer.”

The goal for the sailing community should be to learn from and improve upon past outcomes. Along those lines, one comment rings particularly true: If a large number of boats all leave at the same time and some get into trouble at the same time, how do we prevent the Coast Guard from becoming overwhelmed?

Bennett, The safety aspects of the Everest analogy, signficant as they are, are not the only aspects of concern that could become transferable to the sailing scenario, especially in the more sensitive environments. Alan

Thinks for touching on that aspect. Rallies…the good, the bad, the ugly…are the trend and will only expand.

The concept of marine reserves will come into play much like defined areas in national parks designated for ATVS or snowmobiles.

Bye bye coral.

Tom Chapman

SV Tatoosh

Astoria

Hi Alan

I agree with everything you say – what has happened on Everest in recent years should to just be viewed in terms of safety, but in terms of the environment and cultural degradation, too.

Best wishes

Colin

Not just Everest…recall how the tragedy of Fastnet in ’79 changed a lot of minds on safety and preparedness in rallies and races, and had a pretty radical affect on both boat design and racing rules.

On a different note, I saw a documentary last night on CBC about how the brain navigates (or fails to navigate).

http://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/episodes/where-am-i

One of the throwaway factoids was on an emerging hypothesis that the use of GPS is making us spatially less able to orient ourselves. One wonders about the implications for messing about in boats.

We haven’t done a rally. We don’t even like to “buddy boat.” We’re not even keen on having others aboard during a passage. So we’re not qualified to comment on these specific behaviors.

However, reaching back into my aviation experience, I am reminded of how often “Groupthink” has been cited as the cause of or contributing factor to aviation incidents and accidents — military & civil, private & commercial.

Groupthink usually involves cockpit crew, but it has been shown to extend to larger groups (squadrons, airlines, etc) where a dominant person or idea and social pressure — real or imagined — to conform, or be accepted, or avoid criticism have led to death and destruction. Simply put, “groupthink” kills. Sadly, I’ve seen it happen firsthand.

One senior guy once explained there is a huge difference between “Safely getting there, and got there safely. One is forward looking and emphasizes safety. The other is retrospective and emphasizes having gotten there. The problem arises when the group members begin to merge these concepts in a way that getting there takes precedence over safety without the group realizing it.

Dominant members of the group with more experience and/or self-confidence (justified or otherwise) take control of the thinking for the group — some of that thinking is willingly surrendered to them. The real problem is when that surrender occurs without realization. And it should be noted that, in groupthink, this assumption of control is not a coup, it is usually subtle and even unnoticed — this is not about blowhards, it’s about weakness.

The usual victims are the arrogant and the weak.

Hi Chris,

Very interesting comments on ‘groupthink.’ I agree with everything you said. Nice point to bring up.

+Andy

Hi Chris,

I really like “there is a huge difference between Safely getting there, and got there safely”. The former contributes to survival and the latter contributes to disaster. Andy Chase’s analysis of the “Bounty” sinking is a classic example of the latter at work.

Hei Chris

A few years back we had a tragic accident in the Swiss mountains where are a group of really experienced people got caught in an avalanche. Because it was a military training course, and they were all under orders, there was a deep investigation into why it happened. This were all experienced profesionals, all working as licenced mountain guids in their civil life, and they got caught.

The finial conclution was exactly what you described. The group wanted to do it, they all had done it before. So they went, even doe not one of them would have done it with a costumer. Sad story, but there is a valuable lesson in it.

Regards

Simon

Hi Bennett and Dave,

Thanks for the comments, and good ones at that. Dave, I think you raised the best point – the boats that get in trouble do so because of their preparedness and mindset, not because they are in a rally.

I saw someone comment on the Rule 62 tragedy from a few years back. I was sailing on the 1500 that year, skippering an Outbound 46 as a training cruise for the inexperienced couple onboard (who, by the way, subsequently double-handed down to Trinidad and cruise now in the winter from their base between there and Grenada – Gretchen and David of Callisto are prefect examples of new folks getting introduced to the ocean sailing life in a good way, learning the lessons, being prepared and being successful at it). Anyway, when the Rule 62 thing started, it was a cascading series of small decisions that resulted ultimately in the tragedy. The boat went on the reef because of those decisions, NOT because they were in a rally.

Let’s not confuse cause and effect here.

+Andy

John totally totally true.

My last ocean passage was in December, 22 from Beaufort to St. Thomas, got hammered but expected that in December. Had storm sails up, a good sea berth, Monitor working and hove to when I needed it, made it with nothing broken. But I also didn’t have all that excess crap people are putting on the back of their boats and full enclosures-

Hi John,

I don’t know much about the rallies so I am not really qualified to speak about them but the numbers do seem to indicate that there are issues. It would be interesting to see what the statistics of different groups but I doubt that information exists in an easy way to access.

Something that is interesting to me is how people react to previous experiences. I used to be relatively unphased by experiences that I had and would not get any more or less bold unless something happened repeatedly. Now, whenever I head off, I can think of more things that can go wrong. So far, this has been a good thing as it means that I am better prepared but still out there doing it, hopefully I never get too scared and stopped doing it altogether. As engineers know, your model is only as good as your assumptions and one of the problems with a sailboat is that assumptions are really hard to make. If you designed everything for the worst possible weather ever, you would get a boat that was undesireable for most other conditions so we have to accept some form of risk and do our best to mitigate it.

I used to teach whitewater kayaking and I noticed that I often had a very different reaction to how well someone had done. Often, as long as someone hadn’t swum a rapid, everyone would feel that they had styled it. I always felt that just not swimming does not mean that you did a good job, people often looked wildly out of control. If someone wasn’t actually in control the whole time rather than defensively trying to get through something, then I felt that they were not ready to move up to harder runs.

Your point on weather is very good. When thinking about a coastal passage, I always think about it in terms of whether I can get back into a safe harbor within the reliable forecast window or not. Like others have mentioned, I try to go out on both the good and bad days as I feel it is valuable experience and a great way to test your gear.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Very good point. In the same vein, I’m always very sceptical of the sailor in the bar holding forth about his/her storm tossed voyage. The real seaman tends to be the quite person in the corner who when asked about the same passage says “oh, quite pleasant really, bit of weather, but nothing to worry about” or some such.

For 10 years I’ve witnessed firsthand the ARC Portugal Rally. I see them in Peniche from my boat and also see them sailing close-up from my office through a telescope.

My verdict: Too much emphasis on the party/festive atmosphere stoked by speed egos (inevitable, but dangerous on this treacherous coast). Lots of inexperienced crew going for a joyride. A good party if that’s your ticket.

Hi All,

The AAC Brain Trust delivers again. I primed the pump, but you took it to to the next level.

A huge amount of wisdom that will help anyone that goes offshore, or is thinking about it, including me.

Thank you all so much.

Good job John!

I can’t agree more. It’s not a rant, it’s just saying the truth. As much as Andy wants to and needs to defend the 1500, the requirements don’t insure competent sailors. Look at the Bermuda 1-2. They have a good inspection. This year, Winds 20-30 with an occasional puff to 35. This offered up storm stories at Dinghy club. Really? Boats were beat up. I was having a great race till the wheels fell off Clown Car. Let’s save the rescues for a Sydney Hobart. All captains need to take an honest look at them self. If you’re not cool with 30-40, Don’t go offshore. That’s why God made bays. Money buys you a boat and safety gear but the sea and time on it makes you a sailor.

Hi John

You do a really good job with your website. It must take some time. The links in this post are great. Hours fly by reading tragedy. I’d like to see more big storm stories if you’ve got them. I ran across a long account of actual drogue and sea anchor deployments. It list conditions and results. Morgan’s cloud was in a few events listed. Are you familiar with this? And could you post a link if you know it?

Hi Dan,

Thanks for the kind words. Hum, no I don’t know, sorry.

Dear Andy and Marc,

I was not going to mention it when just Andy mentioned manual bilge pumps offhand, but when you, Marc, brought them up, I thought I should. The issue is the place of manual bilge pumps for most of us cruising: 2 person- husband & wife. I know many experts always include them, but, against the stream, I would want to consider whether a manual bilge pump really has much of a place in a flooding (sinking) situation. Basically, in a flooding situation, you need to find the leak and you need to find it fast. Both crew should be searching for the leak in a planned and practiced strategy as every inch of rising water makes the leak more likely to not be found and the ship lost. Seeing a leak is far more efficient than feeling it. To have 50% (or even 30% if a 3 person crew) on a manual pump that is extremely unlikely to keep up is a dangerous waste of resources. A fully manned boat, yes, put the gorilla on a manual bilge pump, but for most of us: I would suggest an early and loud high water warning, automatic bilge pumps, and a planned and practiced strategy to locate the leak quickly is the way to go. By all means, have a manual bilge pump, many rules demand it, but I would urge it not to be integral to a flooding strategy on a 2 person vessel.

My best to all, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

I agree totally. We have a huge manual bilge pump, but I don’t believe it will help us much in a situation where we get holed, for the reasons you state. In fact my thinking is that even mechanized pumps are of limited benefit, until the hole is plugged.

The key to survival is, as you say, stopping the inflow quickly. To that end we carry two heavy vinyl crash patches, a kit of sponges that are designed to plug holes, wood plugs, wedges, and assorted bits of plywood.

I think that the mentality of a huge pumping system is somewhat of a carryover from wooden boats. In a major storm, these boats would work and often leak quite a bit even though they were perfectly sound. In really bad situations, a seam or two could open up and while the amount of water coming in was quite a lot, a crew could still usually keep up because the actual hole was very small. In a wooden boat, you usually have ceiling planking so you can’t get to a seam that has opened up during bad weather and even if you could, it would be really hard to do anything as seams are beveled the other way.

I agree 100% that the best strategy is to find the leak quickly and deal with the real problem. I still think that a decent pumping system is necessary because you are unlikely to get a truly watertight patch. The yachting monthly video on trying to patch their crash test boat was interesting and the patches worked better than I would have expected although they were in a very controlled situation.

The mechanism of leaking is very material and construction technique specific and I think modern materials favor good patching whereas plank on frame often favored pumping.

Eric

Dick/John/Eric: My liking a manual pump is based on the same rationale as liking a foot pump in head and galley and a lever pump for seawater to the sinks: sure, if you have the amps, staged electric bilge pumps (I have a Rule 3700 now and plan for more) are as nice to have as pressure water, but you have to consider that may not always hold. As I have a metal boat, the bilges are customarily bone-dry. With the limber holes in the collision bulkheads plugged, it is quite possible that a split hose or a failed clamp could confine hundreds of litres of water in the middle of the boat (there’s a 130 cm. deep keel bilge there). So I could lose through a short the pumps there, and keep the separately wired pumps elsewhere. Assuming I fix the leak, the job becomes to clear that water in that relatively confined area. The manual is realistically not going to save us, no, but it allows a Plan B far more efficient than a Scotty B on a stick or even a bucket (the area’s too deep to bail out of the pilothouse).

That said, I carry the usual softwood plugs and will carry the sort of mats most likely to work in a pinch. The manual pump would be essentially for clean up. There’s farm equipment called a “rotary hand pump” that could be used to put ballast water on the high side for trade wind passages or for fuel tank trimming or diversion. To me, to use electricity for these sort of tasks is a missed opportunity to keep one’s rowing muscles in order.

I agree with John…..I’m an RYA/MCA Yachtmaster Instructor/Examiner.. and have seen too many sailors that have a lot of miles but little variety of experience. The sea is a pretty cruel master – I was asked once what I have learned over 40 years of being a professional mariner – I said that “the sea does not give a damn about you” …

I’m heavily involved in proper training – RYA – and wish more people would get a good foundation before venturing out on ocean passages.

Very good article and discussion. I remember similar comments in the UK yachting magazines following the 79 Fastnet as the previous few races had all been light weather affairs.

Can not comment on the rally syndrome as I don’t do them, but often think how much quieter the seas and harbours used to be before the advent of GPS and push button navigation.

Your comment about climate / weather change rang a bell. Way back in the early 80’s I was running a charter yacht / RYA sailing school out of Lerwick, Shetland. Each October for five years dates for the following summer season were fixed, starting with Lerwick to Bergen and finishing some 8 weeks later with a return trip. We never missed a sailing, other than leaving Sunday morning rather than Saturday afternoon, and always got a suitable weather window for the return trip to Lerwick.

Recently, I have failed to make Bergen from Lerwick on two out of three years. Perhaps, I am just getting older but the weather patterns have definately been different with more and stronger easterlies.

All the best,

Sean.

re GroupThink;

The flip side of the groupthink coin are the weather window hypochondriacs who sit in a place like Luperon for months at a time waiting for the opportunity to make a passage to windward with no wind. As you so correctly point out John, the real problem with fall rallies to the Caribbean is the herd mentality. And that is a human tendency that cannot be changed by better organization and decision making on the part of rally organizers.

Fact of the matter is that when you are offshore in a small sailing vessel you are on your own. The presence of the red escape button only serves to obscure that fact. A far better preparation than taking a series of classroom courses and then joining a herd is to take a number of “voyages to nowhere” from your home port. Instead of cruising from pleasant harbor to pleasant harbor next weekend, sail offshore to a series of way points chosen to provide a challenge— preferably when the weather is nasty. Do this a few times spending two nights at sea, and you and your prospective crew will not only know each other but your boat’s strengths and weaknesses, and build a sound basis for decision making for a longer offshore passage.

Hi Richard,

We in fact emphasize the ‘aloneness’ once you’re offshore when it comes to dealing with emergencies. I think the one area, however, where being in a group actually does bring strength in numbers, is in dealing with non-emergencies or medical issues. Most of the fleet year to year has SSB, and it’s very inspiring hearing the stories folks tell of yachts helping out each other on the radio with simple things like recipe ideas, troubleshooting watermakers, engines and other equipment, the occasional pub quiz and sometimes non-life-threatening medical emergencies. When it comes to assisting anyone in a real emergency in storm conditions, other than offering moral support as a friendly voice on the radio (which is indeed worth something), I agree that there isn’t much anyone is going to do – that said, last year in the World ARC a crew was saved in the Indian Ocean when their boat sunk out from under them after they’d done all they could to save her. The conditions were calm, and the transfer of crew to the other boat went smoothly. So it can happen – but people shouldn’t expect it when they’re making their preparations.

Finally, your last point about making cruises to ‘nowhere’ is absolutely essential, and something we encourage crews to do and which almost all of them do – it’s simply wrong to think that we don’t encourage this simply because they’ll be sailing with a group.

All the tips that have come out in this discussion since the original post echo the sentiments of proper seamanship – essentially, that it starts long before you ever leave the dock. A successful voyage ought to be uneventful and free from drama. What I don’t understand is that anytime the topics of rallies come up, there seems to be an invisible assumption that crews forego all of this advice simply because they are with a group. Do people really think that us as the organizers promote the ‘safety in numbers’ fallacy in lieu of proper training passages and qualifications, simply to get numbers in the fleet up? The last thing we want are unprepared people out there, and that’s the whole point of what I’ve been saying – let the SDR bump their numbers by attracting anyone and everyone. I’ll take a smaller fleet of well-prepared cruisers any day.

And finally – and this is the last thing I’ll say about rallies, I promise! – why can’t we just let people enjoy the type of sailing they each enjoy (though I’ll admit the comments thus far have been on the up and up and not really inflammatory)? There is nothing inherently wrong with sailing with a rally – it doesn’t make you any less of a sailor, which I think is the prevailing idea among ‘independent’ cruisers (indeed it was my own idea before I got involved in the organization and actually met some of the sailors, many of whom I’ve made lasting friendships with). And unprepared independent cruisers are just as likely to get themselves in trouble. At their core, rallies are just a social thing. To each his own I say.

+Andy

Hi Andy,

I don’t think that anyone here is saying that they think less of cruisers that join rallies. Generally AAC readers are pretty inclusive. And you will note the last paragraph of my post in which I made clear that this was not about status.

Rather the point is that, in my opinion, and that of many others, the rally model has intrinsic dangers that need to be highlighted. That’s what I did, and what many of the other commenters have done. And let’s not lose sight of the fact that well over a million miles of experience has been brought to bear on the issue in this thread.

Hi John,

I think this whole thread is great – it’s really refreshing to be on an Internet forum and hear almost entirely positive comments. Rare indeed. I guess I wasn’t clear when I made my comments, but I meant to actually acknowledge that fact regarding how everyone has been speaking about rallies. I meant it more from what I usually hear in general, not on AAC in particular. This is a great knowledge base here, and I’m glad to be a part of the discussion.

+Andy

Sheryl & I had done 4 transatlantic passages on our own (2 eastbound and 2 westbound) when we were preparing to cross again last fall. We ended up joining the ARC so we could document the experience for our television program Distant Shores.

It was quite an experience! Here are a few observations from the point of view of sailors who are used to “paddling their own canoe”

– things build to a frantic pace when everyone departs together”. The normal feeling in Las Palmas is much more relaxed as people come and go. Here it builds as the big day arrives.

– safety inspection – nice in a way to have this as its good to have a different set of very experienced eyes look over your boat. But I definitely chafed at some of the “suggestions” eg. we were requires to have white flares, not used for distress they are an ARC requirement. The ARC believe these have some value for lighting a scene of distress. But they also demonstrate how dangerous flares can be during the excellent ARC flare practice session. Now of course I will need to dispose of these flares.

– skippers meeting – excellent weather briefing before the start.

– departure schedule – We have always chosen our own departure day, often delaying to complete jobs on the boat, testing and checking equipment, etc. In the rally there is very great pressure to leave on the appointed day. While most boats were ready, there was one vessel having all her standing rigging replaced the day before the start!

– Delayed start – Kudos to the ARC committee for delaying the start of ARC2012 to get a better weather window. This is very rarely done and there is big pressure not to delay (think all the crews with flights booked out from St Lucia). I was impressed that ARC delayed by 2 days.

– crowded ocean! Yikes!! We have rarely seen other sailboats on our trans-ocean passages. Here was over 200 boats starting the same course at the same time. It was too crowded for my taste especially as sun was setting and only about 1/2 the boats had a transmitting AIS (as we do). Later in the crossing it was nice though – having boats nearby made it more friendly.

– pressure to go fast – we have always crossed at our own pace. I like to have a comfortable passage and enjoy the time at sea. We are not racers. ARC is meant to be a Rally not a Race, but there is a definite sense of a race. I think there were more breakages since people were pushing more than they might on their own.

– Welcome at the end. Normally we just arrive after a passage and march up to customs to clear in. It was quite a treat to have people waiting for us. A crew out on the finish line welcomed us in even though it was 2am and volunteers met us on the dock to catch lines and hand us a rum punch! Wow!

Hi Paul,

A very fair, balanced and useful report, thank you.

Eric, I agree with your analysis. I have only been on one boat where they recorded the hourly number of pumps to empty the bilge. Nostalgia is nice, but I am glad not to be doing so on Alchemy. And you are quite right to point out the necessity for pumping, manual or electric, in the event of a imperfect patch. My interest in writing was for those who might turn to their manual bilge pumps as a knee jerk reaction (or following “experts” advice) without thinking about their big picture flooding strategy.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Marc, Sounds very well thought through. Dick

Thanks, Dick. I think we fellows who give our boats such a great name need to try harder when it comes to contingency planning!