Offshore sailing is pretty safe, but accidents, and sometimes even deaths, do occur.

Most often I read these accounts, learn from them, and move on without writing about them—there’s enough sensationalism, scaremongering, and second-guessing out there in Internet land without me adding to it.

But sometimes I hear of a tragedy that highlights dangerous trends in offshore sailing that could be avoided if they are recognized, and then I do write, but not often—just seven articles over the years.

The tragic deaths of Volker-Karl Frank and Annamarie Auer-Frank on their CNB 66 Escape on passage from Bermuda to Nova Scotia back in June has driven me to write again.

What Happened

First, although I recommend that you read the excellent account over at Blue Water Sailing, here is a brief overview of the acident:

- The CNB 66 is a big boat with a powerful rig that’s highly automated with winches, in-boom roller furling, and two headsails on roller furlers, all primarily driven by electricity.

- Karl and Annamarie had prudently taken on two additional crew for what can be a tough passage from Bermuda to Nova Scotia, even in June.

- Contrary to initial reports, it seems that they were competent crew who performed well in a horrible situation, not passengers.

- Escape encountered un-forecast gale-force winds.

- While reefing, the boom got out of control and the mainsheet hit Annamarie.

- Karl went to help her, and he too was hit by the mainsheet.

- Both were severely injured.

- The US Coast Guard pulled off an amazing helicopter evacuation of the two injured sailors—the rescues those men and women perform never ceases to amaze me.

- Tragically, both Karl and Annamarie died of their injuries.

- The two surviving crew, who had cared for Karl and Annamarie until their evacuation, while doing an amazing job stabilizing a very nasty situation, were eventually taken off by a US Coast Guard cutter and the boat abandoned.

Rounding Up To Reef

The account makes clear that the skipper, who had sailed the boat for at least a couple of years, felt that reefing could only be safely accomplished head to wind, with the engine running to keep the boat’s bow up during the process.

Was Rounding Up Necessary?

There are endless debates among proponents of in-boom (and in-mast) roller furlers about whether or not rounding up head to wind is required while reefing, furling and/or hoisting.

What the truth is I don’t know, but what I do know is that Hans, a deeply experienced friend of mine with in-boom roller furling, has recently found, over the course of a transit of the Mediterranean followed by an east to west trans-Atlantic, that his in-boom unit, on his Farr 56, is only reliable if the engine is started and the boat held head to wind while hoisting, furling or reefing, the same as on Escape.

And, further, the procedure was the same on the 93-foot Jongert Vivid (photo above), that I was guide and navigator on for a cruise to and from Greenland.

Defining Downwind Reefing

We also need to be clear on what “downwind reefing” really means. For example, what is being demonstrated in this video is not what I would define as downwind reefing. The sail is still being luffed and the true wind is forward of the beam.

What Matters

Anyway, whether or not rounding up is required with a given system is not the point.

All that matters here is that so doing was the standard procedure on Escape and seems to have become so on many boats, both those with mechanized systems, and even those with slab reefing.

Alternative

But there’s a much safer alternative:

On our last boat, a McCurdy and Rhodes 56, for over 30 years and well over 100,000 miles, most of it shorthanded, reefing was a trouble-free, low-stress operation that Phyllis and I could accomplish with zero drama in less than three minutes, and that I could do in a little more time when single-handing.

How? When things got rough, we would reef with the true wind abaft the beam. And in moderate conditions when on the wind, we would crack off a bit to reef. See Further Reading for how.

We never, ever, rounded up head to wind to reef.

I have lost count of the times we reefed in rising gales without trouble this way, but one memorable occasion stands out where we had to put in three reefs in quick succession and then claw the main down, as, in the space of a couple of hours, the wind increased from twenty knots to the high forties with gusts into the screaming fifties in the notorious crush zone off Cape Farewell, Greenland. Much the same, or possibly worse, conditions than those Escape was dealing with at the time of the accident.

Sure, our experience was exciting, but there was no drama and little danger.

Well setup slab reefing is way easier to use than most people think. And when reefing is this easy we will do it early and often.

How Downwind Reefing Works

Why is reefing downwind safer and easier than upwind? Let’s compare:

Lower Apparent Wind Speed

According to the account, when the reef was attempted the wind was blowing gale force with higher gusts. To round up a boat into those conditions, with only one reef in, particularly a boat the size and power of Escape, is a terrifying prospect that those who have never experienced a gale at sea will have trouble imagining.

But a good metaphor is that the mad flapping of the sail(s) with the accompanying noise is akin to being in the middle of a thunderstorm, but with no gaps between the detonations—total sensory overload.

And on a boat the size of Escape, the sheets can, if slack even for a moment, become blurs of wildly pulsing, potentially death-dealing energy.

Contrast that to reefing downwind in heavy weather when the sails never flog and the sheets are always under tension.

Motion

A well-designed sailboat has an amazingly benign motion when running off or broad reaching, even when a bit over-canvassed in heavy weather. Turn up into the wind and that same boat changes in an instant to a wildly pitching monster where moving about can only be accomplished on all fours and from handhold to handhold.

The account mentions 6-meter seas. My guess is that’s probably high given the short duration of the blow, but no matter, even turning upwind into seas of 4-meters significant wave height would make it impossible to stand safely on deck, and very difficult to operate the complex gear required to reef on Escape, particularily with the high level of precision required to reef without a jam with an in-boom system.

Boom Control

Before reefing, Escape had a boom preventer rigged, as is seamanlike.

So if they had been able to do as Phyllis and I did on our McCurdy and Rhodes 56 and just ease the preventer a foot or so, while bringing in the mainsheet to move the sail a little off the shrouds, and then snug the preventer back up tight, prior to reefing, the mainsheet would have remained in tension throughout the manoeuvre.

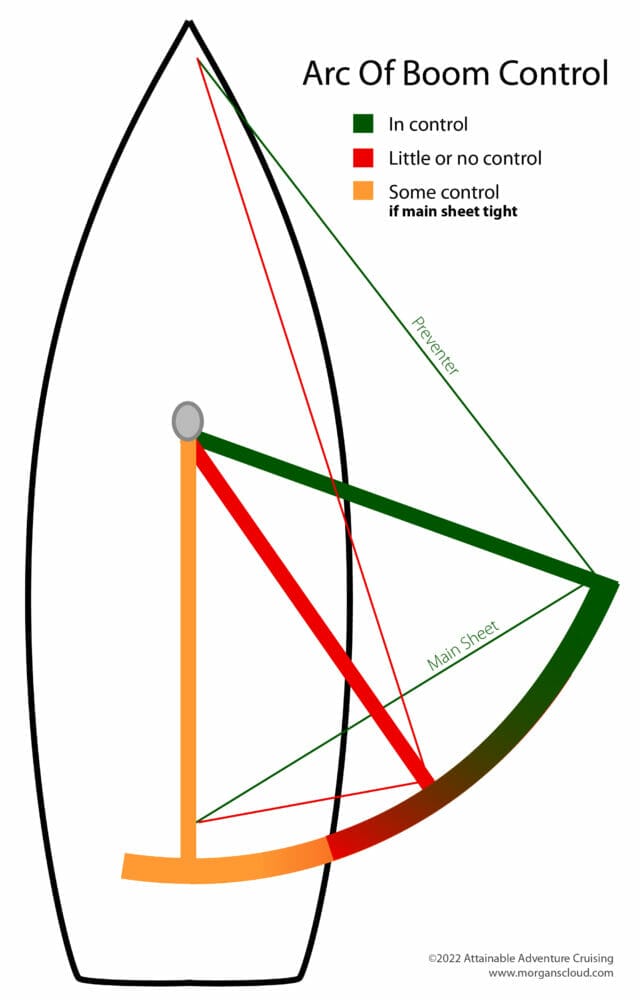

This is just simple geometry: With a properly rigged preventer opposing the mainsheet, there is no way for the boom to get out of control. See the diagram above.

But when the crew trim the mainsheet in as the boat is turned into the wind, that equilibrium drops off quickly as the angle between the preventer and boom decreases, to the point where the boom potentially becomes a free-swinging demon well before the mainsheet can be tightened enough to bring it back under control.

And even with the mainsheet all the way in, with the boat head into the wind, the boom will continue to oscillate wildly back and forth because the pull of the sheet is now vertical, rather than horizontal and opposing the preventer as it was with the boom further out.

This is further exacerbated as soon as the reefing starts on a boat with no topping lift like Escape, since once the tension is off the leach of the mainsail as the halyard is eased, the only force opposing the mainsheet is upward pressure from the compressed gas in the rigid vang. The result is that the boom thrashes back and forth even more than before as the boat rolls and the gas pressure changes, alternately tightening and slacking the mainsheet—we had the same type of vang and no topping lift and so I’m writing from firsthand experience.

Potential Disaster

With wildly flapping sails, flailing sheets, violent motion, and the boom in a position where control can be lost, we have an intrinsically high-risk situation. One mistake or gear failure and that risk can turn into tragedy.

Conclusion

My thinking on the accident causes in descending order of contribution to the tragedy:

#1 Going Head To Wind To Reef

We don’t know for sure what happened in the moments before the mainsheet hit Annamarie—jammed preventer, failed mainsheet winch, override on the drum and/or steering error, are just some possibilities—but the fact is that the mainsheet went slack as the boat was rounded up.

And the specific cause doesn’t matter for our purposes here, since none of those problems can ever happen when reefing off the wind because the mainsheet is always in tension against the preventer.

Therefore I believe that if the crew of Escape had not been either forced by the limitations of the in-boom furler to turn head to wind, or by the assumption that so doing was required, these two fatalities would never have happened.

Blame In-Boom Roller Furlers?

It’s no secret that I’m not a fan of in-boom or in-mast roller furlers.

That said, many competent sailors I respect have them and there is no question they have some advantages. For example, Hans and his spouse, the friends I mentioned above, daysail their boat way more often than we ever did our McCurdy and Rhodes 56.

That said, in my opinion, any system that does not allow true downwind reefing is a trade off. In the case of in-boom furlers, that translates to added convenience for added risk.

#2 Deck Layout

I have long had concerns about modern trends in deck layout, but that’s an article in itself.

For now, suffice to say that, as far as I can see on Escape, the danger area from the mainsheet encompasses a lot of areas that the crew must cross repeatedly and operate other winches controlling the headsails and preventer in.

#3 Boat Size

There is no question in my mind that boat size and power played a role in this tragedy. If the boat had been say 40-feet long, would the mainsheet have killed? Less likely, for sure.

That said, the only accident-caused fatality in the history of the Marion/Bermuda race was boom related on a boat just 44-feet long.

So out-of-control booms and mainsheets are dangerous regardless of boat size.

But this tragedy certainly raises the question, how big is too big, particularly for shorthanded amateur crews? I have tackled that one in another article.

#4 Too Much Sail

From the account, it seems that Escape was caught with just one reef in by the rapidly rising wind and sea state, exacerbating the danger of going head to wind to further shorten sail.

That said, there is no one with a lot of offshore miles under their belts, including me, who has not made the same mistake, which is why this is at the bottom of the cause list—our boats should forgive our mistakes.

Recommendations

So what can we learn from this horrible tragedy? Here are some recommendations that I think will reduce the chances of a repeat.

These are not ordered, because I believe they are all of equal importance.

Safe Reefing System Purchase Criteria

I don’t like that on three boats I know of with these systems (Escape, my experienced friends’, and Vivid) it is standard practice to start the engine to keep steerageway while reefing or furling. What if the engine is down?

So, if it were me buying a mechanized system, being able to reef without the engine and at least while cracked off on a reach, and better still off the wind, would be my number one selection criteria.

Offshore is Different

When considering reefing systems we must not kid ourselves that a system that requires going head to wind, or even close, that’s easy to use in sheltered water inshore, will be the same offshore in big waves. That’s a different world and it won’t be.

Reef Early

If we decide to install a system that requires going head to wind to reef, it’s even more vital than normal to reef early and deep before the conditions get gnarly.

Topping Lift

I’m a dyed-in-the-wool topping lift hater, but I make an exception for boats with in-boom furling that must be turned head to wind to reef, hoist, and strike the mainsail.

In this case, for the reasons I detail earlier, I agree with George Day (Blue Water Sailing) and strongly recommend a topping lift to supplement the rigid vang.

Mainsheet Safety

It is one thing for smaller boats, and even bigger racing boats with full-on race crews, to have a mainsheet positioned so it can potentially hit crew members going about the normal tasks of sailing the boat.

However, my recommendation is that on boats of say 40-feet and up, particularly those intended to be sailed by shorthanded amateur crews offshore, the mainsheet should be placed so that there’s no way for it to hit a crew member in a normal working position. Once again, George Day and I are in agreement.

Experts Only

It’s important to realize that, counterintuitively, a boat fitted with these mechanized systems requires more skill to sail safely than one fitted with a good slab-reefing system.

I totally agree with George Day in his comment to the account:

in-boom systems can be finicky, and riggers will often note that the systems are best used by experienced sailors who understand all of the forces at work when handling big mainsails.

As an example of how finicky, the week before I joined the 93-foot Jongert Vivid, the experienced professional skipper, who was new to the boat, had destroyed the main halyard by making a slight mistake while hoisting. And for our entire voyage to Greenland and back the skipper banned anyone else from operating the system, and even he was clearly still learning throughout the passage.

That said, after I left the boat he did complete a circumnavigation, so clearly he got the system figured out.

But the scary thing is that mechanized mainsail reefing systems are sold to those new to offshore sailing as making things safer as well as easier, or at least that is implied by much of the marketing material.

But, in my view, these systems are only for use by deeply offshore-experienced sailors.

I recommend learning to sail offshore with slab reefing before you take one of these things on. That way you will have an appreciation of the loads and be in a position to make an informed decision about which system best meets your needs.

Learn To Reef Off The Wind

Talking of slab reefing, if your boat is so equipped, I recommend learning to use it on all points of sail, including running off the wind—see Further Reading.

Two More Things:

Not Their Fault

Nothing I have written above should be taken as a criticism of Karl and Annamarie or to in any way imply that they were the architects of their own misfortune.

The Horror

While writing this article I read the account of the accident at least five times, and each time I experienced a visceral flood of horror, partly because I too have experienced a bad injury and waited for rescue, and therefore can graphically picture the terrible hours after the accident, both for Annamarie and Karl and the two crew who cared for them—Phyllis, who cared for me, suffered from the resulting trauma for years afterward.

I strongly encourage all of us to really think about this accident, and look at our own boats and procedures with a critical eye and an open mind.

As I said at the beginning of the article, offshore sailing is pretty safe. But it’s not risk free, and being dogmatic about the way we do things ups those risks. Something I need to remember as much as anyone.

Free Articles

We published this article outside the AAC paywall, where it will stay as a tiny memorial to Karl and Annamarie, fellow voyagers on the sea.

We have also moved the how-to-reef-downwind article outside the paywall. See Further Reading.

Please share these links with others (buttons below each article). That said, copying the articles or republishing is a violation of our copyright. Reasonable length quotes are fine, as is republishing the boom danger graphic, as long as you link to this article.

A big thank you to AAC members who fund this site, and particularly those who have voluntarily increased your support, thereby making this sort of pro-bono work possible.

Further Reading

Free to read:

Membership is required ($36/year) to read the following chapters in our Online Book on safe and easy sail handling, but the introductions can be read for free:

- Reefing from the cockpit.

- Number of reefs and how deep.

- Proper preventers and how to rig them (three chapters).

- Why the use of a boom tackle to the rail would not have helped Escape.

- Rigid vangs and topping lifts.

- An in depth analysis of in-boom, in-mast, and slab reefing systems (two chapters).

- The story of the salvage of Escape

- Much more on safe and easy sail handling.

Hi John,

Agree completely and well said. A couple of thoughts:

I am sure you cover it in the referred article, but I do not believe it can be reiterated enough: slippery mainsail track is not only a huge convenience in all mainsail handling, but I believe, a great addition to safety. On Alchemy, slippery track basically allows reefing and dousing the main easily and safely while going downwind: a procedure we accomplish often: rounding up in high winds and seas is, blessedly, an event in our past.

I would also want to underline that many “labor-saving” devices like mainsail furling systems, demand an increase in skipper and crew discipline commensurate with the decrease in labor: and that there is danger often when not disciplined and vigilant. It is hard to go far wrong with slab reefing, even when tired and wet and being thrown about.

And, for all of us, please note: every time there is a call-out for search and rescue, there is danger for the SAR crew sent. Our part of the “deal” if you will, is that we go to sea equipped in such a way as to make a call to SAR least likely and a result of bad luck and not poor preparation (and I say this as a general comment in no way reflecting on Escape and its crew and this tragedy).

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Excellent article John, definitely appreciate the insight. We have accumulated a meagre 5000 nm this last year and as newer full time sailor, I find myself pondering a lot of the techniques I was taught about sailing over the years. We were definitely instructed to turn into the wind to do so. I always assumed it was hard on the rig, specifically the sail slides/ luff, but thought the flogging of the main had to be worse. I actually started reefing without turning upwind but scolded myself as being lazy, for not wanting to ‘deal’ with turning, controlling a violently flapping main, or centering the main. I feel better now, it makes sense.

Hi Cory,

Well done to figure this out yourself. I was taught to round up to reef and it was years before I figured out that was bogus. So if this article reassures just one person (you) that reefing down wind is safer, it was worth the effort to write it.

And as a sailmaker in a past life I can also assure you you are right about the damage floging does—sailmakers love sailors who let their sails flog.

By the way, your comment illustrates something I have learned over the years of running AAC: Us old salts can learn a lot from someone new to offshore sailing, if we keep an open mind, because you question old “wisdom” that is very often wrong.

Thanks for the excellent article John. I don’t want to front-run your future article, but I’d encourage folks who do have in-mast furling to experiment with reefing downwind. This tragedy drives home why heading up is risky; at minimum, it makes sense to know if you really have to do it.

We have a Hood Stowaway in-mast system on our 44 foot cutter (so my experience is based on more modest loads than those involved on larger boats). We’ve found it furls just fine downwind so long as you coordinate slacking off the outhaul with furling the sail (both can be done from pretty much anywhere in cockpit by taking a couple of wraps around a winch drum for control and releasing the outhaul clutch). The technique is the same as furling a jib, with the outhaul replacing the active sheet.

We haven’t had to do this in a true gale. If for some reason we couldn’t get the sail in without altering course, I would head up just a bit to depower the sail, leaving the boom prevented, much as you would leave a whisker pole secured in its bridle while furling a poled-out jib.

At least with in-mast furling, I think that the advice to head up comes from a desire to protect the main against chafe on the slot in the mast. Heading up may be a nice refinement in settled conditions but not something I would be worried about if we had to reef in a hurry.

A better solution, in any wind, is to furl to windward. If you spin the foil in the direction of the wind, the furled mass of sail keeps it off the slot after the first few wraps. (If you already have a reef in, this will only help if you happen to be on the “correct” jibe based on your earlier furling. For a cruising sailor on a passage, more often than not you will be.)

Thoughtful article John, thank you.

Having a Leisurefurl in-boom reefing on our 47 foot sloop, this is a helpful analysis.

Upwind-reefing is a really good option on our boat in any wind strength, so I don’t see this as a major hazard, rather a factor to monitor. Leaving our jib set then releasing the mainsheet, inverts all our full-length battens. This backwinds the main and holds the boom up towards the wind, calming it magically.

The boat motion also quietens and we slowly fore-reach with zero sails flogging. We can also heave-to to reef, which quietens things further. We hardly ever start the engine to take in sail, and then usually when approaching our destination.

But since your earlier articles on reefing, we have been experimenting with reefing downwind with the mainsail fully in and also fully out. It works best with the boom topped about 10 degrees above horizontal (5 degrees is normal for reefing upwind). We keep the halyard bar tight – in the Leisurefurl video you referenced above we would have three turns on that snubbing drum, whilst hauling in on the downhaul using our power-winch, reefing slowly inch-by-inch. This keeps the luff of the mainsail really straight and largely limits bunching-up at the mast. It is this jamming up of the mainsail against the mast and gooseneck that is the issue for in-boom reefing off the wind.

So far we have had success with this to 30 knots and find broad-reaching with the mainsail fully out has worked best, because the apparent wind is then lower. Speed is your friend, but as you say these are things that need experience and practise.

Since a recent mechanical failure with our furler, in a seaway we now have both the topping lift and vang on hard to stabilise the boom and prevent it from bouncing around.

Our mainsail track is in front of the companionway and we are separated from it by our hard dodger. So there is absolutely no chance to be struck by the mainsheet or the boom, as all reefing happens in the cockpit, aft.

This accident has similarities with the tragic loss of life on Platino you wrote about in 2020:

https://www.google.com/url?client=internal-element-cse&cx=011492909488923319915:p-1ttyt5fbm&q=https://www.morganscloud.com/2018/10/02/amidships-preventers-a-bad-idea-that-can-kill/&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwj2hrPgwtz5AhXqRmwGHYuLB_AQFnoECAEQAg&usg=AOvVaw1RxvFkOfxo7MkY52IqQtus

The positioning of the mainsheet was a major factor with Platino too. So deck layout would be my #1 hazard, as I just don’t like tracks and mainsheets that cross in or near the cockpit where people are working or relaxing.

I have a scar under my chin from an argument with a mainsheet that ran across the cockpit on a one-tonner – a SOB to gybe in winds over 25 knots. The mainsheet won by TKO, slamming me on to the winch I was grinding…!

Rob,

I am glad to read your comments, which confirm much of my experience with Leusurefurl boom on our 46 foot sloop. I cautiously experiment with pushing the envelope of standard LF procedure.

I have tried downwind furling with main sheeted all the way in, but only in light wind, and engine idling in case I need it to move apparent wind forward. Maybe I will push that.

But I am hesitant to try it with boom all the way out, due to concerns for the universal joint rotating at angles exceeding 45 degrees (per manufacturer). With the sail off the boom, i have observed the U-joint while rotating at various boom angles, and was not reassured.

Apart from U-joint rotation, boom out resulted in boom housing impinging on mast, stressing gooseneck bracket, at angles that seemed less than those I might desire when DDW. I will look at that with sail up when DDW.

I have learned to actively work the topping lift. Like you, I find 10 degrees is better than 5 for all reefing and furling. Also, it seems essential to apply topping lift when reefed, as the after end of the boom is not as supported by the leech which has moved forward.

When it comes to the furling boom, I have a healthy respect, bordering on fear, and worry that I will break it, the boat, a person, or cause unforseen aggravation by not executing properly. But with repetition and experience, my confidence has grown, perhaps because having identified some of the risks, I can avoid them.

Hi Michael,

Good points. The issue we have with furling with the boom centred, is we roll a bit DDW unless we are surfing (then we are upright and on rails). This is thanks to our flat bottom run and wide-stern quarters aft (although not extreme by today’s trends). This makes keeping the boom centred long enough to reef safely in a large seaway impractical – when we centre the boom, we come off the surf.

With our experiments furling with the boom out, we have aft swept spreaders (again not extreme) so we are anyway limited to how far the boom is out. In our favour, by 25 knots we have always got at least one reef in the mainsail, especially at night when we often will have two reefs in the main.

I am cautious about this too, but I have a friend with a catamaran and Leisurefurl boom (they have really swept-back side stays) and he confirms they have reefed downwind in the manner I describe above – otherwise they would have to make the “turn-up of death” for a cat…he says it’s not pretty.

Rob

Hi Rob,

Very good point that trimming the boom into the centre while sailing downwind will make the boat impossible to steer safely once the wind and sea state is up.

Also good warning on the “turn up to death” for cats.

Hi Rob,

Thanks for your experience on using the a roller furling boom. Invaluable given that you have had it quite a while.

I do need to point out though that the technique of having the jib set to backwind the main with the bow up to windward would not work in the 40 knot winds and a four meter (at least) significant wave height that Escape was experiencing. Having that much Jib out (enough to backwind the main) and drawing in that much wind would put the boat on her beam ends and might easily result in a knock down during the round up phase. The loads on the Jib and its rigging would also be terrifying.

I base this on our experience that in that much wind and sea the maximum amount of sail we could safely show while heaved to was the triple reefed main and no headsails, and that on a very stable 56 foot boat.

The other problem with that technique in that much wind is that, as you say, you are slowly forereaching and that ups the chance of a knock down or even roll over in that much wind and sea state. Heaving-to is only safe in that much wind if the boat stays in her own slick by moving slowly sideways.

More here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/when-heaving-to-is-dangerous/

Remembered a trick that we use to assist in reefing on and off the wind. We have tied our mainsail with the Dyneema ties about 20mm further aft than our sailmaker Doyles set it originally. This helps keep the rolled sail away from the back of the mast and allows a deeply reefed main to continue to roll on its mandrel.

Rob,

From your comment I understand you have shifted the sail 20 mm aft on the mandrel by shortening the clew outhaul lashing and adjusting the tack lashings, which would move the luff aft relative to flexible feeder portion of luff track. That had not ocurred to me, but our luff is already about as far aft as seems proper relative to luff track feeder.

What I have done to accomplish a similar result (I think), is lift aft end of boom more with topping lift, and avoid slack in luff above above mandrel by 1) maintaining adequate halyard counter tension while furling and 2) keep the forward portion of sail backwinded by jib.

We keep the boom less than 45 degrees out, backwind main with overtrimmed jib, and do not turn fully head to wind but definitely have apparent wind forward of the beam. This has worked nicely for us up to 27 knots true sustained and waves 6-8 feet. But, when reading his comments, I immediately took to heart John’s concern about this technique in stronger wind or bigger seas. I am determined to avoid that.

Another example of AAC helping me to improve my judgement without always having to live through a first hand bad experience. Thank you!

Hi Michael,

Yes, this is exactly what we have done.

Early-reefing will be even more our “way” offshore and off-the-wind. Luckily we have an easily driven yacht where slowing down needs more attention than going fast.

Rob

We have sailed our Moody 40 about 20,000 offshore miles. We regularly reef our in mast furling main while running downwind. It requires correctly setting the topping lift (we have marked ours at the right spot) and coordinating the furling line and out haul, which is not difficult. My wife and I sail double handed and either of us can reduce sail single handed. We do not have and do not trust electric winches. We feel that they give a false sense of control to couples who otherwise may not have the strength or skill necessary if the electrical system fails.

Dear John,

The article in ‘Blue Water Sailing’ is a sobering read. Thank you for the link, and also your own words of wisdom.

A thing that struck me was there seems to have been some confusion about the best way to get help. Allow me to make some suggestions :

In my experience, satellite phones are a far better technology than anything based on radio. Especially the sort of light weight radio transmitters carried on sailing boats.

My first act therefore would be to call the operations centre for the relevant SAR organization. In this case :

By all means activate the EPIRB and call on VHF. The EPIRB distress signal however, will eventually arrive at USCG Virginia. Furthermore, the USCG will know immediately if there are commercial vessels in a position to help, and those vessels are much more likely to hear (and pay attention to) a powerful USCG radio transmission. Or satellite phone call.

Given that the sat phone is our primary emergency communication medium, I issue laminated cards with relevant emergency numbers to every crew member. In bold type and large enough so no one has to look for their glasses. The USCG is always on the card no matter where I am because I figure they will be able to contact local SAR if I cannot do so directly for any reason.

A final point : ‘InReach’ has an emergency function also based on satellite technology. I have never used it, but their cell phone based messaging system works pretty well, even in the Arctic. So it is potentially, a good (and cheap) back-up for the SatPhone.

Let us hope however, that nothing bad happens to any of us. As you say, the ocean is dangerous, and the line separating us from disaster can be very fine.

Best regards,

Grenville

Hi Grenville,

I did/do much the same.

I will mention that when in Europe, I had the Falmouth CG on speed dial. For much the same reasoning, I felt they were the go-to SAR reporting station for Alchemy for the time we were in the Med and for our years wandering around Northern Europe: they could facilitate SAR for where we were most anywhere. There was also the consideration that they spoke English, our primary language, which made less likely communication confusion. And they were reported to facilitate medical advice. Their phone number as I knew it 6+ years ago is below, but please check that their number and capacities have not changed.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

1. Falmouth Coast Guard, +44 132-631-7575.

a. Using their Medical Advice Link Calls they will connect you to Portsmouth Hospital where there are doctors experienced in medical emergencies at sea.

Hi Grenville,

All good points.

One clarification, I never wrote that that the “ocean is dangerous”. My first sentence of the article was the exact opposite. I believe that for those of us who go to sea in a seamanlike way, it’s safer than getting into an automobile.

At least in a boat offshore we are in charge of our own safety, rather than being at risk from the drunk, overtired, drugged or texting fool coming the other way in a car.

Indeed… if you say “Every day, I pilot a 1500 kg vehicle on near-collision courses to 400 other vehicles piloted by unknown strangers, with an average closest approach of 3 metres at a relative speed of 180 km/h” then you sound insane, yet many of us do just that.

The emotional difference, in the offshore boat situation, is that the situation is changing over minutes or hours in a way that we cannot escape. A car driver who’s on the verge of panic can always pull over, stop, turn on the 4-way flashers, close his eyes, breathe, get out, and stand on solid ground. A sailor who’s on the verge of panic must face it, overcome it, and do her job anyway.

From the designer’s standpoint, we need to keep that in mind. Systems that look effective on paper might not be effective under adverse conditions. Equipment that works perfectly at the trade show demo might bind, jam, or otherwise cause all hell to break loose when it’s loaded up with 30 knots of wind and an exhausted crew member makes a seemingly minor mistake.

I would like to see a lot more attention given by designers, across this whole industry, to making sure that sail power can be safely reduced in any wind conditions while on any point of sail. We should never demand that the crew intentionally put the boat in a marginally-controllable or out-of-control situation for the sake of working around an inherent limitation in the vessel’s basic design and its systems.

A second vote for InReach. I was in contact with Falmouth coastguard every 3 hours for several days using an InReach and it worked really well. The ‘texting’ approach does have some advantages as you can send an update or respond when you are not distracted by other things.

Dear John,

I have no doubt that Volker and Annamarie were lovely people and their deaths a sobering and tragic loss.

However, you focus the blame on their furling boom. While a factor, I think this blame is misplaced. I believe their biggest mistake was buying a boat too big for them to handle as a couple. A boat in the 40 – 45 foot range is far less likely to have killed them and they would not have felt the need to bring on extra crew with their attendent language problems and lack of familiarity with the boat.

Why a couple feels the need to have a 65 foot sailboat makes no sense to me, and yet these big, complex, energy-intensive boats are becoming increasingly common. This should be a lesson to all sailors thinking of buying a bigger boat: don’t buy one so large that you can’t control the sails manually, if necessary.

Hi Gino,

Actually I did not blame the roller furling boom. What I wrote was that it is always safer to reef down wind and if they had done that the tragedy would never have occurred, and I stick by that based on well over 100,000 miles on a boat that while not as big as Escape is 56 feet.

I then pointed out that reefing systems that require turning head to wind increase risk. That’s very different from blaming the roller furling boom, and I stick by it and would doubt that anyone who has actually tried turning head to wind in gale force conditions offshore would disagree.

I also specifically mentioned boat size, and will expand on that in another article, although I don’t believe that was the primary cause.

There is even a reasonable argument that turning head to wind in gale force conditions in a 40 foot boat to reef could have been more dangerous given the much more violent motion of a smaller boat in that seaway. One of the things that surprised me a lot when I moved from 45 to 55 feet was that in many ways sail handling was easier on the bigger boat because of the more stable platform to work on with less risk of a green water coming aboard.

For example, a smaller boat might, when going head to wind, be swept from stem to stern by a big wave, which can kill or maim too, when Escape would not have been. And the boom on a smaller boat tends to be lower, and so more of a threat to the crew.

Bottom line, like most every accident as sea, this one was caused by a bunch of interrelated factors not just one, like boat size, or roller furling boom.

And the argument the boat was too big might hold water but for the fact they brought on two additional crew.

My boat, with no vang, just a plain tackle for the kicking strap, does have a topping lift and the rest of the features, except a slippy track for the main, slab reefing.

Reefing head to wind or, at least fine reaching, or in the heave to position, is how I have always reefed. In rough weather, it is stressful simply due to the noise and motion. The other truism, I believed, was that hauling on the reefing pendant without the tack over the gooseneck horns, was a fatal mistake that would rip the clew out the sail.

I am so disappointed in myself, as I don’t consider myself blind to improvements and safe ways of working.

I will now try downwind reefing and master it, with the kit I have, and where required upgrade. This is obviously a no brainier, as it works, and with my single set of straight spreaders, should be straightforward enough. I can already think of some efficiency improvements on my boat.

Thanks for posting the article.

As a by the way, my reefing pendent are coloured red, yellow, green; 3, 2,1 respectably for easy identification.

A question: When the luff is slacked by 18”, does the luff need to hauled down in strong winds, or does wind in sail pressure work it down?

Hi Alastair,

Our old-fashioned boat is set up just as you describe and can be reefed without difficulty even when running deep downwind. The area of the mainsail is about 360 sf and the luff is around 44 ft. There are only two reef points, each very deep, on the theory that if you are going to reduce sail there is no point in half measures.

To reef I take up as much slack out of the topping lift as is easily possible, slack the halyard to hook the tack ring onto the reefing horn, harden the halyard up again, winch in the clew pennant (winch is on side of boom), tie off however many reefing points are easily accessible and slack the topping lift back to its original position. Off the wind there is no need to touch the sheet, kicking strap or fore guy (if rigged) although letting out the sheet helps reduce the loads if we are on the wind.

The track is an old-fashioned external T track and the slides are bronze. The sail comes down without any strenuous hauling.

The topping lift, John’s least favourite piece of gear, runs from a cleat at the mast, up to the masthead and down to a block on the end of the boom. A stopper knot restrains the boom end at the block and a strong piece of shock cord along the boom keeps the slack out so it does not flop around wildly.

Following John’s advice, the reefing pennants are double ended, running through rope clutches to a winch on each side of the boom so all or most of the work can be done standing or crouching by the windward side of the mast.

I have sailed on big, powerful boats and like the comforts and fast passages they provide. But I completely agree with John that potential for getting into serious difficulty and therefore the need for crew training and discipline increases rapidly with size of the boat and degree of mechanization. There is a sweet spot, probably in the 35 to 45 foot range (better measured by displacement), where comfort and manageability for a double handed crew are probably best.

Wilson

Hi Alastair,

Glad it makes sense to you and it sounds like downwind reefing should work fine with your set up.

As to pulling the tack down, a sharp tug will usually do the trick, but it will also tend to slide down as the reefing pennant comes in, so I have never found it necessary to pull it down until we get the reef pretty much ground right down.

Also see Wilson’s comment, and he does not have a slippery track either.

Hi Alastair.

(Edit: I saw John had replied while I was writing this comment, but I let it sit here anyway.)

Others can probably answer this better than me, but the luff will not come down on its own. On my boat (40 ft) when reefing downwind, the sail will be plastered around the spreaders, shrouds and whatever is up along the mast if I let out 18″ on the halyard at once. I believe John have covered his reefing procedure well in his article (which is how I learned to reef), but I let out just a bit of halyard, and then pull the luff down by hand and take in on the reef pennant/winch. Maybe 4-5″ at a time? keeping the sail pretty much tight and in shape the entire time. It is quite intuitive once you try it. I also have some tension on the vang/kicker and mainsheet to help the mainsail not being taco-wrapped around the shrouds and spreaders. From crude memory I would say I keep the boom at around 50-60 degrees to keep the sail off the spreaders, since the slack halyard will twist the sail a lot! Just try it a couple times in less wind, and you’ll figure it out well. My main culprit is the lazy-jack lines can catch the batten-tensioners along the luff, but that’s due to a poor placement of the sheave for the line on the mast with the main 90 degrees out to the sides (sheaves/lines too close to the mainsail track).

As an aside, I can’t really see how a topping lift or a rigid vang have much use during this procedure, as the wind in the sail will keep the boom up anyway, but I may be wrong?

Hope this helps, and I’m sure others can explain better.

Hi Alistair and all,

There were questions on getting the luff of the sail on its track down when going downwind. What works on Alchemy (40 feet):

Reefing and dousing the mainsail going down wind can be an easygoing and safe task.

With both slippery track and with conventional track, the job is easier if the sail is pulled aft and has less surface area to plaster against the shrouds and spreaders. Track cars are more likely to create friction if pulled to the side so getting them (more) facing aft is a help.

To that end, I find centering the boom to help and that using the reef outhaul lines to pull the sail aft reduces friction and allows me to tease the sail down: sometimes using the reef tack lines to pull (having the reef outhaul lines tight also keeps the sail better behaved).

With reef outhaul lines pull the sail aft, then let a few feet of halyard go, then pull the luff down: repeat. Pull the reef outhaul lines tight as needed. Takes time, but there is no rush: the sail is unlikely to suffer any damage, and you are working on a stable predictable platform.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

I have never found any need to centre the boom when reefing downwind, even before I had a ball bearing track, and furthermore doing so ups the risks when reefing downwind in anything over a moderate breeze since the preventer is no longer effective and the boat will be much more difficult to steer with the boom overtrimmed.

In fact I would say that having to centre the boom defeats 75% of the purpose of reefing down wind in the first place.

Given that I strongly recommend that others who are learning to reef downwind do so without bringing the boom into the centre, and if they can’t make that work, then modify their procedure and gear until they can in all wind speeds up to strong gale.

Hi Arne,

See the linked post on downwind reefing for the important role of the rigid vang (or topping lift) in making downwind reefing easier and also how to keep the sail off the shrouds while reefing.

Hi John.

Maybe this gets a little beside the point on this article, but anyway, I re-read the reefing article. I still don’t see how the topping lift or rigid vang does anything, as the tension on the reefing pennant is keeping the boom up, and the tension in the vang/kicker strap is pulling down on the boom way harder than the spring in my vang. Maybe I am doing something wrong, or maybe it’s just my boat/rig that behaves differently?

Is the intention to keep the boom in a fixed up/down position? If that is the case, then my vang-spring is nowhere near strong enough to do that on it’s own. I have not found this to be a problem, as I keep the tension on the reefing pennant. This also keeps my sail from touching the spreaders, while I keep the boom far enough out so the preventer is doing it’s job. I just do smaller increments than your 18 inches. I do have a much smaller sail than your boat, so doesn’t take so long, and I probably get away with some techniques that are not so refined yet. Any input is greatly appreciated!

Arne 🙂

Hi Arne,

The most important part of this is that the vang keeps the boom from coming up to meet the reefing clew and so keeps the leach tight so it does not droop off and rub against the spreaders and shrouds.

Ideally the spring (or gas) pushing up in the vang will keep the boom from drooping as the halyard is eased, particularly when shaking out a reef, but that’s less important, and not vital for reefing, but if the vang spring is not strong enough to do that it’s a good idea to have a topping lift. Also note that most vangs allow you to adjust the pressure of the spring.

John,

Thank you for the post. I think that it is good to study such tragedies to learn from them. When I was into rock climbing I use to read the annual Accidents in North America Climbing to make myself more aware.

I look forward to your article about boat size, how big is too big. I hope in your article that you will also talk about rig size; specifically split rigs such as ketch and schooner rigs as such rigs could be easier to handle physically. I have become open to a split rig to achieve being Intercoatal Waterway (ICW) friendly. I have read that a ketch can split the rig to make it more manageable for short handed crew, but I have not read much about a schooner rig.

Prentiss

Hi Prentiss,

Thanks for the kind words on the piece.

And yes, I will write about rig size, in fact probably most about that.

That said, having sailed a bunch of miles on one, I don’t think most ketches increase the safe handling much, if at all, and schooners are something I just don’t have enough experience with (read zero) to write about.

All that said, I have always thought the Herreshoff Marco Polo was is an interesting way to break a big rig up into manageable pieces. In fact back in the day I designed and built a set of sails for a boat with that rig.

After over four years living and sailing full time on our catamaran, we’re still working to find the best way to reef our large square top main.

With no vang, we find that we simply have to head up to at least 50 AWA to get the sail down without being fully on our shrouds (which are pretty far aft).

Then we fight a boom that is trying to point to the sky.

The single line reefing from the factory is not a good system and we continue to try ideas to help. For now we simply reef very conservatively and usually start engines and point up.

Hi Ray,

Yes, you definitely need to get that fixed. Rounding up to reef in a cat is doubly dangerous because of the the capsize risk. The right answer is a rigid vang, but you could use a tackle to the rail, just don’t be tempted to use it as a preventer, since it’s not safe for that. Check out the chapters on vangs and preventers: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/rigging-sails/book-sail-handling-rigging/

Hi Ray,

Also check out Colin’s chapters on fixing single line reefing. The other option, and often the best, is to scrap it, and go over to double line, or line and hook. The sad fact is that 90% of production boat reefing systems are crap and need a complete rework to be safe and functional.

Hi John, The shape of our boat, Najad 405, and position of the shrouds make it awkward to run preventers all the way to the bow, they rub on the shrouds, we have swept back spreaders so the boom can’t go out too far anyway. We currently have the preventers running through snatch blocks amidships near the shrouds, do you think that is hazardous?

Hi Mike,

Yes, that’s hazardous:

https://www.morganscloud.com/category/rigging-sails/book-sail-handling-rigging/

Not sure what the issue is, but there is no reason you can’t rig a proper preventer on a Najad 405 or any boat with swept back spreaders. See these chapters for how: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/rigging-sails/book-sail-handling-rigging/

You taught me about downwind reefing through these articles and we used it aboard our Brewer 44 often and without fuss. We had a tides marine track and a strong-enough pre-installed winch that I could crank down the clew under full load.

We never really saw any extreme conditions on our voyages yet, but picturing turning into relatively small 6′ waves and 25kt true, let alone the horrible conditions that this unfortunate couple experienced, is just blood chilling.

Condolences to Volker-Karl and Annamarie Frank.

Hi Conor,

Glad it’s working for you on the Brewer. It’s always great to hear success stories like yours.

As you say blood chilling, and yet it seems that so many people still think that reefing head to wind is a viable option, mystifying.

Hi John,

Thank you for the link, it was good to get a proper accounting of this incident and it truly sounds horrifying. I can’t imagine trying to do first aid and contact rescue services on a boat that is out of control like that. And the fact that this resulted in 2 deaths despite extraordinary efforts is really sad. I heard some surprisingly critical commentary right after the accident and this article makes it seem like something that could happen to many people given how builders, vendors and magazines want to set up boats these days.

Reefing has been an interesting journey for me over the years starting with roller booms, then going to slab reefing, then learning to sail traditionally rigged vessels and finally back to slab reefing most of the time. With traditionally rigged vessels, one of the first things that jumped out at me actually once I got over the fact that they truly dropped the anchor was that I had no idea how to safely reef them underway. Unfortunately, it turned out that many of the captains and crew didn’t either. The weight of boom, gaff and sails is quite often over 2 tons and sometimes a lot more and the 25+ reef points are not there to keep things tidy, they take load. Upwind was relatively doable, you just had to get the boom triangulated, typically with quarter tackles unless it used a single lift. Downwind, I eventually realized that the trick was actually to drop the sail completely in an “emergency drop” then tuck the reef then reset. This meant training the crew to let out something like 400′ of halyard in a controlled manner in the time it took to do a slow tack which was something like 30s, doable but it takes significant practice and prep (ballentining, etc). Then after tucking the reef, you would do another slow tack or round up and have something like 30s again to haul things far enough up that they would allow you to finish off the wind. The process of rounding up was always exciting and you got the whole crew lined up along the rails hanging on like crazy so that they could get right to work once things leveled out a bit. Most of the captains preferred to start the engine and jog into for the whole process but I found the motion to be horrible and those boats have so many lines that could easily foul the prop that I never wanted to take that chance, the issue was less stalling the engine and more losing a halyard or sheet and having to reeve a new one in those conditions. So I love how easy our current slab reefing setup is.

I agree with you that this boat violated a few things that should be requirements for shortening sail. Using the engine really bothers me when reefing. From a fault analysis, you suddenly become single fault sensitive to one of the most complex items onboard that can easily be taken out of commission by rough weather for a variety of reasons. And now that I have tried downwind reefing as you suggest on our own boat, I agree that being able to reef on at least a broad reach is a requirement as well. To be honest, the first time I tried it was also the first time we fouled the prop on this boat and swung downwind, the only way to get the main down was by tightening the vang and grinding in the reef lines but then it was surprisingly easy. How these requirements are actually met still leaves plenty of room for different solutions but at least you know how to evaluate those solutions.

One thing that I like to try to avoid is times when someone has to be hauling in on a winch with significantly varying tension on the line. Coming head to wind in big seas is a classic case for the mainsheet. If you have enough turns on the drum to prevent slipping when the sheet suddenly loads up, you will also have enough turns to potentially cause an override. Since these situations are not entirely preventable, I like to have everyone practice regularly and we generally discuss number of turns before a maneuver and our best person goes on the winch if it is a really critical time. Another problem is that some boats set up with all high modulus gear can break stuff if you don’t slip the sheet a little when it slams, since Drew talked about using nylon for traveler lines we have been doing that and it definitely gives you more margin for error.

One other little thing that I have learned the hard way is that if you are relying on the autopilot when reefing and are enough on the wind that you will dump the mainsheet and just reef quickly with the sail luffing, you need to make sure that you don’t need to adjust the autopilot tuning prior to going to the mast. I let the sheet go and scurried forward once to minimize flogging and suddenly realized that the boat was falling off rapidly. Shortly before gybing the autopilot caught up and overcorrected and we ended up with a wild roundup but there was a period where I seriously considered unclipping and just getting out of the way in case the rig came down in a wild gybe.

Eric

Hi Eric,

I always wondered how you guys on big classic fore and aft rigged vessels pulled off reefing. Now that I know, it only increases my admiration for tall ship officers. The way these professionals take relative neophytes and turn them into safe mariners in a short time, and do that in one of the most dangerous environments imaginable (the deck and rig of a traditional sailing vessel) has always amazed me.

I’m also thinking that maybe big schooners are the most challenging since individual sail sizes are much bigger than on square rigged ships, even bigger ones? I know that every time I see Bluenose out sailing I marvel at how they handle that mainsail without killing anybody.

Also very good point on the dangers of, and skill required, to handle a line that is rapidly loading and unloading on a winch. One of the things I love about downwind reefing is that the entire evolution can be done without that happening.

You comment makes me wonder if the start of the tragedy was when one of the two new crew was put on the helm for the round up. It takes a lot of skill, and familiarity with the boat, to round up in the dark and that sea and wind state while coordinating with the main trimmer.

Hi John,

Well one of the secrets of reefing on big traditional boats is that most captains try not to do it. Sometimes this means just saying goodbye to the rail and a ratline or two as they go underwater for a few hours, sometimes it is carrying a big “fisherman’s reef” and sometimes it is doing an emergency main drop and jogging under foresail often with the engine on. One of my favorite pictures of all time is Bluenose II broad reaching with gusts reportedly over 50 with all 4 lowers up in the Gulf of Mexico, they must have been doing something like 18 knots. I suspect that they had gotten to the point where reefing was going to be seriously scary so they just hung on and hoped. One of the most ridiculous speed records I know of was when the original Columbia (I may be mixing this up with Puritan) left Gloucester under full lowers unknowingly into what I believe was a back-hand tropical storm and they dropped anchor in Boothbay 4 hours later, that is a distance of not quite 90 NM. The boat that impresses me most is Europa which they take to unbelievable places and I can tell you from having sailed her in calm weather that while she is handy for the type, she is still quite a hard boat to sail. Some of the boats like the later fishing schooners actually have decent stability and marginal downflood angles but others are quite scary, many square riggers never recovered from getting knocked on their beam ends off the east coast of Argentina purely by the wind.

Yes, the mainsails on schooners can get quite scary large. Most of the ones that people are used to seeing like the Maine Windjammer fleet are not huge, the American Eagle has the biggest up there at around 2000 ft^2. Once you start talking about boats like Columbia and Bluenose II, they are dealing with about 4000 ft^2 in a single sail plus a huge amount of spar weight. You may be right that schooners have bigger mains than even the course on the big square riggers but at least you don’t go aloft to furl them which is quite the experience regardless of the weather. One thing I didn’t mention is my previous post is that when reefing huge gaff mains, one of the most common issues is breaking all the mast hoops. When the gaff is all the way up, the tension in the peak halyards keeps the gaff pushed forward against the mast and the parrell beads across the gaff jaws are tightest as a backup. However, during raising, the throat halyards take the majority of the load and it is much worse when you are reefed so the gaff tends to pull away from the mast and puts all the pressure on the mast hoops which often break. So you need to do reefed sail raises with the peak significantly higher than normal. On small boats, the gaffs jaws are often shaped so that the retaining loop around the mast is tightest during raising but this is not the case on big vessels as it is impractical to build. Kind of off topic for this post but it shows how different and interesting different rigs can be to work with. Just like how I would be totally lost working with a roller boom, I have never done it and could make some huge errors each time I hit a new situation. By the way, there are plenty of accidents on traditionally rigged vessels, those of us who keep some touch with that world hear about accidents and near misses quite regularly.

Certainly a helming error could have contributed to this, even a person very experienced with the boat would struggle between the waves and too much sail area trying to cause a wild, rudder out of the water roundup.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Thanks for another fascinating comment. As you say learning about different rigs is fascinating, particularly for me since I have only sailed on a gaff rigged boat for a couple of weeks, and that was 60 years ago.

For other’s interested in the difficulties and dangers of sailing traditional sailing vessels, I highly recommend Tall Ships Down: https://www.amazon.ca/Tall-Ships-Down-Albatross-Baltimore/dp/007143545X

My condolences to the famiies that lost loved ones. Tragedy can strike when we least expect it, Having read all this, I have to ask: why is in-mast or in-boom roller furling becoming so common? I thought it was to make things easier, but hearing the reports of those who use it, it obviously doesn’t do that, except perhaps in conditions when you don’t need to reef. Marketing?

Hi Terence,

Good question!

I wonder the same thing. I think the key reason that these systems have become so popular is that most production boats have truly terrible slab reefing systems. Also, even in sailing courses, reefing is often taught badly. And then there is the prevalent idea that we must turn up wind to slab reef. The result is people have a few bad experience with slab reefing and then fall pray to the marketing for more complex systems, when all they really needed to do was improve the slab system on their boats and learn how to use it properly.

Hi John, I was the engineer and 1st mate on Vivid for over a year. We sailed from Europe, through the Caribbean, down from Panama, all the way to Antarctica, and then back up to Ecuador in that time.

I have no idea how many times we reefed, but the default system was captain on the engine and boom furler controls, and me at the mast watching luff tension and how it rolled onto the boom.

It was a terrible system that required the two most experienced crew, and regularly created a “we’ll reef at the watch change, so we don’t have to wake up anyone early” mentality.

We made it work, and did over 30,000 miles in a year without injury. But everything you’ve said has reconfirmed my distaste for that system.

I’ve been a member since buying my own boat in ~2015. I used your reefing model as my guide. It has allowed for short handed-or worse, sailing with toddlers- passages from South Brazil to the Azores. So

I owe you a big thanks for your insights!

Zac

Hi Zac,

That’s invaluable information, thank you. Amazing that you guys managed that boat safely for all that time and in such challenging places. She scared the hell out of me.

Also great to hear that the skipper hired an engineer. That was one of my primary recommendations when I left the boat. Jongurt should be ashamed for selling that boat to owners on the basis that she only needs a small crew and no engineer. As I remember there are only three berths for crew, and crew mess is the size of a rabbit hutch. I was lucky and was allocated one of the guest cabins, which was good of the owner, particularly since it meant his sons had to double up.

And thanks for the kind words on the site, and for being a member.

Your memory is right about the crew cabins. My bunk was like a poorly ventilated coffin.

Also, if you remember, it was extremely difficult to furl the headsails alone. To do it safely you needed one person to operate the hydraulic foot button while the other eased the sheet. Not impossible alone, but once while 5nm from Cape Horn with a big burst of wind I screwed it up and shredded the genoa.

If you’re the reason they decided to make a permanent engineer’s position, I’m in greater debt to you than I thought. A month after I got the job we took on crew to sail from Brazil to Trinidad, two beautiful young women who were better sailors than I’ll ever be. I fell in love with one of them and now we’re married and have two kids on a sailboat together. It all started with that job. So thanks!

That is a lovely coda to an otherwise rather grim thread. Thanks!

Hi Zac,

Not sure I can realistically take the credit for your marital happiness, but reality is so boring, so I will take it!

As Wilson commented, your story brightened my day.

Anyway, your point on the level of coordination required to operate these systems without breaking something is well taken. I had a demo the other day from my friend Hans on operating his in-boom systems and it was exactly that, that struck me most forcefully.

Thank you for the sensitive analysis of this tragic accident. Annemarie and Karl were wonderfully kind and vibrant individuals and a loving couple. We met them in Antigua in 2021 and spent several fun evenings aboard Escape. Karl loved showing me ( a fellow gadget nerd)all of the bells and whistles aboard Escape-it was a technological showcase. His background in CNC machine tools gave him a solid grip on all of this tech, but my impression of this type and size of boat was that it is too much for, as you said, amateur sailors. I know another 65′ boat of similar design that is sailed by a former professional ocean racer-perfect for him. But Annemarie was usually quite seasick on passage, and not technically oriented and I can only imagine the horrific scenario of that night as things cascaded awry. All we can do is try to learn from this tragedy and know that Annemarie and Karl perished together pursuing their dreams-not necessarily the worst way to go.

Brian on Helacious, currently exploring the rias of Gallicia.

Hi Brian,

That’s interesting, and sobering. Makes sense to me. Thanks.

Very sad story and interesting analysis John. Thanks for the breakdown, I learned a valuable lesson.

I just completed an Atlantic crossing on a 46 foot boat with in boom reefing. I have to say the thing scared the bejesus ou of me. Firstly, it weighs something like 800 lbs ! The skipper usually heads to winward to reef but the only time we didn’t, the main started rolling in crooked, like when you drop a roll of toilet paper and try to roll it back perfectly. Good luck! End result, we only put one reef instead of two and rolled the head sail all the way in. The boat got very unbalanced and the boom would sometimes dip going down some waves. It was blowing force 7 with 3-4m seas. The autopilot broke shortly thereafter. Was the extra strain on the autopilot caused by an unruly boat the cause? It sure didn’t help. Some problems cascade into others. We eventually unfurled and re-furled under more controlled conditions.

During the 20 day passage, we didn’t crash gybe once, thank god. I can’t imagine the damage that behemoth of a boom could do to a boat, let alone to its passengers. You see, the mainsheets were attached to the middle of the cockpit in front of the helm. We gave those sheets one hell of a wide berth when the wind was abaft. The short of it is that I can easily see how this accident occurred. I can see how proper seamanship can reduce the risks, but I’ll be sticking with my slab reefing, thanks.

Hi David,

Thanks for the kind words.

Very good point about the extra danger of the heavier booms required with in-boom systems, I had not really brought that point out. This reinforces that bigger boats with in-boom system should go with carbon for the boom.

And scary that things got that fraught in just a Force 7. Very scary to think about how things would have gone if the wind had continued to build with only one reef in and the boom already dipping.

Like you, I will be sticking with slab.

I am still getting used to the in-boom furling system that came with my Able Apogee 50. But I, too, was struck by the potential danger of the heavier boom swinging back and forth over the deck, or crash-gybing (the main traveler is anchored to the pilothouse and I wondered whether a crash gybe would either rip the traveler off or rip the pilothouse off!). The boat has a good preventer setup, but as John has noted a preventer cannot control the boom at all angles. Happily, the boat also came with a boom brake, a piece of gear I had never used on a boat. For that reason I hadn’t made its use a priority on early passages on the boat, which resulted in some wild boom swinging which caused damage to the boom. My mistake. So for my most recent passage, from the Chesapeake to southern Georgia in November, I made sure to set up the boom brake. It worked extremely well to help cinch the boom in place when rolling in lighter breeze and control the boom in gybes (all planned, thankfully). The result was a lot less stress or worry about the boom swinging or crash gybing. My conclusions: 1) the extra weight of in-boom furling systems can be a major safety or structural issue. 2) As a result, I would consider use of a boom brake a near-requirement with in-boom furling systems.

I’ve sailed a Valiant 42 with in-boom furling about 24K nmi, much of it single handed or short handed with my 93 pound wife. It took me a couple of years to really figure out the furling, which isn’t fabulous, but there are a couple of things. First, you don’t need to engine to furl or reef. If you sail as close to the wind as possible with just the headsails, you can get the boom close enough to the center of the boat to furl the sail with no pressure on the main. With full battens and the heaviest sail I could buy, the sail doesn’t flog much. I have done this in over 50 knots of true wind.

The V40 and V42 have built in preventers with blocks and cleats, and usually you can lead the lines to spare winches. There is also a topping lift. This means that you can always control the boom. I really really like having a pair of permanently installed preventers. In a pinch you can use them instead of the main sheet & traveller.

So, while I couldn’t reef while going down wind, after the first year or so, I never had to start the engine to reef.

One of the big plusses in my mind for in-boom furling is that you don’t have to roll the sail into the boom to get it down. A big sail flopping around on the deck in a storm is bad, but you should be able to just pull it out of the track.

For me, the scary things about Escape are the main sheets in the cockpit and the sheer scale. I especially don’t understand having the main sheet flopping around in the cockpit in a cruising boat. It’s like having a big lathe always running in the bedroom. Eventually, someone is going to get caught.

Hiu John,

I agree with your analysis, and the points you make about the size of the boat and the dangerous position of the mainsheet. Also that it is possible, at least in some circumstances to reef with in-boom without starting the engine or turning up into the wind, although that is, I think, partly dependant on boat size and how hard it’s blowing. See the link below, for more on that, including a video.

That said, in my view none of this changes that once we have to round up, even as much as you do, to unload the mainsail to reef, the boom is no longer under effective control because of the small angle of the preventer. So for me the root cause of the accident remains the same: having to turn up far enough into the wind to take the pressure off the sail before reefing.

As to debating the merits of in-boom, we already have two in depth articles covering that, so if you have further thoughts on that, please share them there: https://www.morganscloud.com/2022/10/09/in-mast-in-boom-or-slab-reefing-convenience-and-reliability/

I just watched a video about this accident, posted some time ago by the new Practical Sailor editor. (How I miss the old paper PS!) Anyway, that was the first I heard that both the main preventer and the main sheet parted during efforts to reef. If they went head to wind, I am not sure how that happened. Anyone know?

Hi Terence,

As often happens with that guy, he got a lot wrong in that video, in fact more wrong than right, if memory serves. If you want the best info on what actually happened go the Blue Water Sailing article I linked to in the article above. My own information, partly informed by what my friend Phil, who was the salvage master, found, is that neither broke but rather the boom got out of the control while, or maybe after the preventer was eased. Anyway, be very careful what you take from those PS videos. He also got a lot about the Platino tragedy wrong. Here’s the real story on that one: https://www.morganscloud.com/2018/10/02/amidships-preventers-a-bad-idea-that-can-kill/ and https://www.morganscloud.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Gybe_Accident_Report.pdf

Hi John, very good points you brought up. I am wondering how can I adopt reefing off the wind for my boat. I have a behind-the-mast furling main (old Famet roller furler) that came with the boat I bought used. I am just wondering if the mainsail would be loaded to a point that it cannot be furled in while sailing downwind. With the mainsail being loaded, I fear the furling system can fail if the furling line is winched hard resulting in something unimaginable. I have always rolled in the mainsail rounding up to wind, as was taught in most sailing school, because the sail is the least loaded. Any tips and comments that you give would be most appreciated.

Hi Ee Kiat,

Sorry, I don’t have any suggestions since I think your concern of overloading the furler is justified. This is an intrinsic issue with any type of roller furler (jib, in mast, in boom, etc) since all of the torque is concentrated where the drive mechanism joins the mandrel or foil and I have never seen any unit where the max safe torque is specified or a unit with any way to monitor said torque. The result is that we can’t tell reliably when we are getting close to the force that will twist off the mandrel at the joint. Because of this all manufactures I have seen require unloading the unit by ragging the sail. This is not that big a problem with jib roller furlers because we can always hide the sail behind the main, but that’s not an option with main furlers.

Hi John, thank you for your insights and thoughts. The multiple occasions that I have to winch very hard to furl in the mainsail often gave me the jitters, expecting something to break at the back of my mind. Thankfully it never happened, yet. However, I am not sure if the torque required to winch in the mailsail will be lower sailing downwind or with a flogging sail as I have yet to try the former. Thinking aloud here. A flogging sail may be kinder to the furling system because the loading, although highly erratic, may not be very high. Also, the short unloaded moments in the flogging may help to furl in the sail. Of course, the flogging of the sail is not good for the sail. I will definitely try winching in the mainsail going downwind on my next sail.

On another topic. I didn’t get any notification on your reply to my post here even though I am “following” all your post. I do get your replies to other posts though! I only got to see it after reading your new topic on ” The Intrinsic Fragility of Furling Systems”. Thank you.

Hi EE,

I can attest that the loads going downwind for reefing/dousing a conventional mainsail are generally moderate. On a previous boat with conventional track, I used the outhaul to take the weight and pull the sail aft and off the spreaders while I “ooched” the sail down by hand getting a few inches to a foot each ooch and Ginger taking the slack produced with the appropriate outhaul. For 2 decades I have had slippery track and the job is far easier: still done by hand.

Also, I take in my headsails by hand with wraps around a winch and can assure you that I am very careful not to let the sail flog: a flogging sail may have moments of little pressure, but when it has its moments of high pressure, I am very glad to have wraps around the winch.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

That’s fine, but do keep in mind that Ee Kiat is dealing with aft of mast roller furling with no way to blanket the sail and no way to know when he is approaching the point he will break something. So this is really nothing like a slab reefing system, as you have, where the loads are not concentrated at a single point of possible failure as detailed in the recent tip. https://www.morganscloud.com/jhhtips/the-intrinsic-fragility-of-furling-systems/

Point being, just because you and Ginger did not break anything, does not mean he won’t. I think he is dead right to be concerned and ultra careful. These systems are way more fragile than those that you and I are used to.

Hi Dick, thank you for sharing your experience. As John mentioned, I have a furling mainsail and it does have it pros and cons. I am in fact very tempted to switch to the tradition slab reefing method but the amount of details needed get it done properly is daunting for me. I will have to do some research and then decide if I should bite the bullet.

Hi EE,

Yes, that is one consideration I had in mind when I wrote: thinking of you and others with or considering RF gear on their mainsails. Slab reefing is just, to my mind, far safer and “mistake” proof, in part because it depends on less gear which the skipper has to guess as to how much to stress. Better in other ways as well.

My best, Dick

Hi Ee Kiat,

Thanks for thanks. I’m sorry it was not a more encouraging answer.

As to not getting a notice. Not sure what happened but I’m pretty sure it’s nothing weird and just that you had not subscribed to follow this particular comment thread.