Question

Member, George asked:

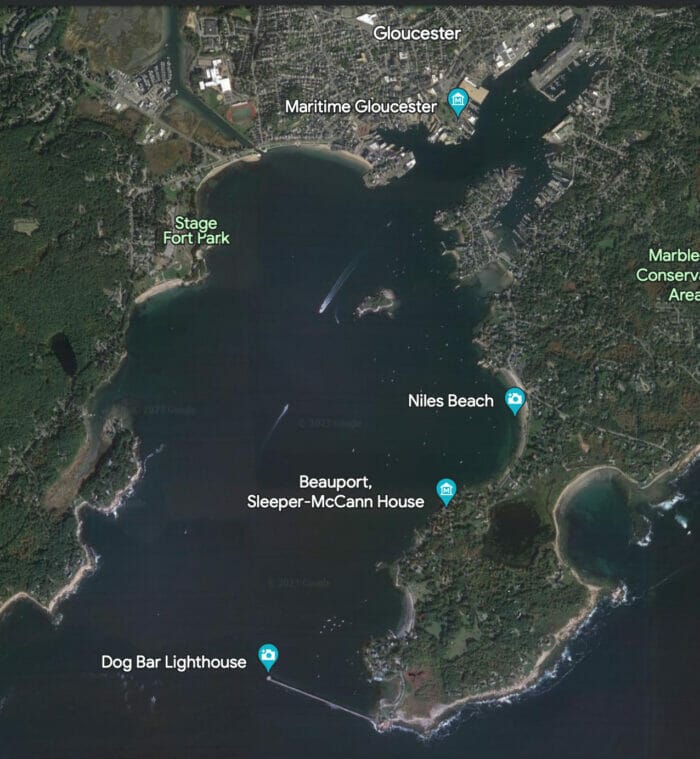

I’m presently faced with challenge of a transatlantic delivery Maine- Azores and beyond.

Boat is old 1978 NY 40, Palmer Johnson built. Pretty solid for IOR era as it was intended for Bermuda races as well as inshore events. Stickey issue is the 12 gallon fuel tank! I don’t like lashing 5 gallon jugs on deck nor approve of diesel storage anywhere below without approved design tankard…

…Barely considering propulsion, just battery charging for auto pilot and house loads, probable 14+ days at a stretch, 40 gallons seems minimum. We’re fitting an old Navik wind vane, so if light conditions, if it doesn’t break we can augment the Garmin auto pilot. 4 on board so hand steering is also an option.

I have a 20 gallon approved for diesel, can be installed below deck flexible tank. Thinking about installing that under aft bunk.

I’d still need 4 more 5 gallon jerry cans & suitable plumbing for safe fuel transfer to main tank. Any words of wisdom?

Answer

As you say, stowing cans on deck is not a good option.

The good news is the NY40 sails well and there should be good breeze on that voyage, so as long as you watch the weather and make sure not to get too far south into the Bermuda-Azores high, you should be able to sail the whole way.

That leaves charging. I’m thinking the best answer is a Watt & Sea hydro generator. That should provide all the electricity you need, as long as you are careful and hand steer some so the fuel can be kept for propulsion.

Expensive, I know, but by far the best solution to this problem and a longterm fix for the boat’s small tank, too.

I don’t much like the idea of the flexible tank because of chafe issues. I have been on a boat when a diesel tank ruptured at sea and it was beyond horrible!

So how about adding a small rigid tank? Would be a good upgrade, anyway, not that hard to do, and you have time.

Even if only say 12 gallons, that would bring the total up to an acceptable amount for the passage, since you would not need any for charging.

The other idea would be say two to four cans below, maybe in a cockpit locker, well padded, and filled as Rob suggests. Given you will have charging covered off, you can wait for calm to transfer, and may not even need to do that.

Anyway, good on you for not giving into the temptation to lash a bunch of jugs along the lifelines, as is all too common, and horribly un-seamanlike.