Have a quick read of this account of a race crew getting hit by a nasty thunderstorm when approaching their home port of Gloucester, Mass.

Done?

Anything jump out at you?

The first thing that hit me is that they never even considered waiting offshore for conditions to improve, or even daylight, before trying what turned out to be a very dangerous approach.

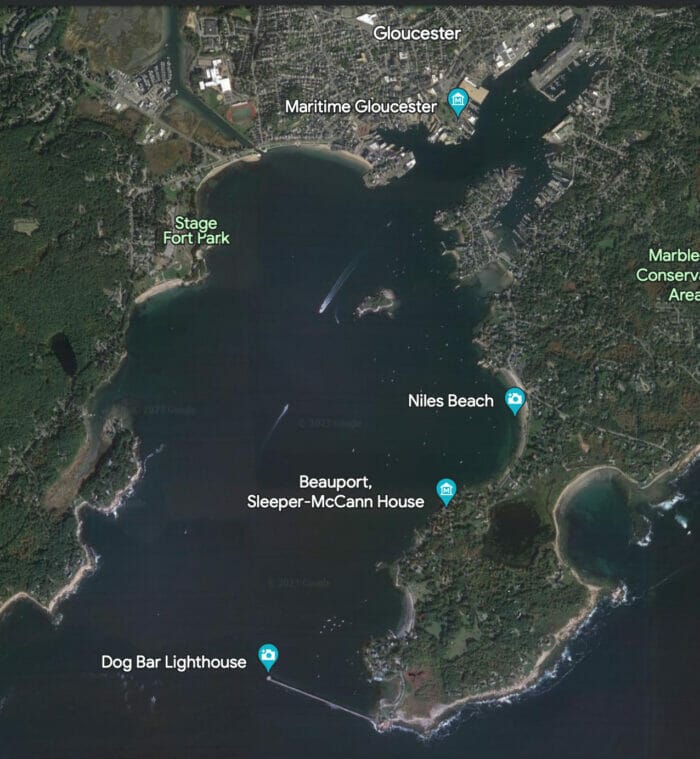

Sure, it would have been rough out there but the wind was in the North so they would have been in at least a partial lee from Cape Ann.

What about running off for Cape Cod where they could have rounded up under the Hook and anchored with no lee-shore danger?

Don’t get me wrong. I was not there and Mass Bay can be a bad place, particularly if the current is running against the wind, with limited sea room in a northerly. Maybe they made the right call.

But by entering Gloucester they were taking huge risks because of the breakwater under their lee. They got lucky on the aborted mooring approach but it could have gone very differently: hitting another boat, getting their mooring gear or someone else’s around the prop…the list is endless. A simple engine or steering failure could have have ended in a nasty wreck.

Have I made the same mistake? Yes. In fact, that’s why this jumped out at me.

I try to never forget:

- It’s not the sea that kills sailors, it’s the hard bits around the edges.

- The very human, and understandable urge to get home can lead us to bad choices.

- Always consider ‘staying out there’ as one of our options.

Threats compound quickly and need to be mitigated early. When did they first have knowledge of a dangerous Wx approach?

Hi James,

I only know what’s in the account. That said, that area is prone to thunder storms so not going out when they are forecast would result in very little sailing over the run of a summer. On the other, other hand, they were within cell phone range and could have used say Windy to check for the proximity of a bad one. Radar can also give us advanced warning, but it does not say if the boat was so equipped.

Hi John and all,

In the article, there was the suggestion to the crew to get the radio ready on ch 16. We almost always have the radio monitoring ch16 when underway. In addition to multiple other benefits, we have been forewarned of “stuff” coming our way on more than a few occasions by hearing a commotion on ch 16. I have also been known to make a “securite” call when a squall has hit out of the blue and I know it might surprise others.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

When we have internet access, I find lightning maps https://www.lightningmaps.org/#m=oss;t=3;s=1;o=0;b=0.00;ts=0;y=29.497;x=-95.4053;z=4;d=8;dl=2;dc=0;tr=0; better than windy https://www.windy.com/?36.844,-80.420,4,m:eRdacYr for locating thunder storms.

Giving up on entering the harbor is like turning around on Everest 200 yds below the summit. I guess the greatest error was not knowing that the storm was coming. Then they could have made an informed choice about entering the harbor. If they knew it was a squall, running before the storm would have been a good option. Not knowing, running off could have left them on the lee shore of Duxbury and playing bumper cars with commercial traffic coming into Boston. They never would have made it around the Cape.

Hi Bruce,

I disagree. Plenty of people have died on Everest because they did not turn back when close to the summit. In fact from the reading I have done (quite a bit) pressing on to the summit because it’s so close is the single biggest reason for death on mountains.

And there are other options than running off, including heaving to.

I also can’t see any reason that they would not have made it to Cape Cod and got under the lee (south side) of the hook. In fact I have done just that when waiting for daylight to approach the Canal with a north wind.

Hi John,

Thanks for sharing, I hadn’t seen this. The writer is a local from Gloucester who is a character and a good story teller, people in the Massachusetts sailing scene will know him. I am pretty sure we were anchored in Gloucester inner harbor just off the harbormaster’s dock that same night in a nice protected spot but on 3:1 scope as it is tight in there and it was high tide. I think we had around 35 gusting 45 in the inner harbor for about half an hour. Of the 3 anchored boats, we didn’t budge, 1 moved a little but not a lot and the last one dragged into someone’s dock a few hundred feet away narrowly missing some rocks and seawalls. That one had 3 men aboard and when they started dragging, I starting blowing an air horn at them and shining our spotlight on them but I couldn’t see anyone on deck until they were against the dock. The reason the harbormaster was out is that when I couldn’t get those people’s attention, I called them but the boat was dragging fast enough that they hit the dock before the harbormaster arrived.

Back to the subject at hand, I think there were several potential options that would have been acceptable especially as these storms were going to be relatively short lived, the front was well forecast and they were very clearly on radar. You are right that Cape Ann would provide a perfectly good lee in this. I don’t see a need to run off to P-town as you would have gotten 1/4 of the way there and the whole thing would have been over but that would have been an option if this were an actual prolonged gale. Also, they could have motored up the harbor on the west side to the NW corner and dropped the hook without putting anything dangerous in their lee if they really needed to get out of it but being in racing trim, they may not have been prepared to and there definitely are wind directions that isn’t true for. The writer would also know that there are harbormaster moorings there that are almost never full and have plenty of maneuvering room. To me, one of the great things about Gloucester is that it is usually reasonably safe to enter and if there is a problem, the whole harbor (okay, not quite but you wouldn’t naturally try the bad spots) is good holding and reasonable depths so you can just drop anchor and then sort stuff out. They docked on the lee side of the dock they ended up on which I think shows that it had abated a huge amount by the time they made it up that far.

Given the short nature of this, the waves in unprotected waters would be unpleasant but not dangerous. I would have probably tried to pick a spot with very few pot buoys outside of the harbor and hold approximate station there, we have line cutters but I don’t want to take that risk. I do worry a bit about the backside of these storms as every now and then, there is a strong wind from the other direction as it passes so I try to be ready for that although it is quite rare. We had a very similar situation as we approached Rockport just before dark a few weeks ago and I could quite clearly see things on both NOAA dopplar radar on my phone and our own radar so we hung out a few miles off until it passed and then went in and had a pleasant night. We have had a lot more strong fronts this summer and general pop up thunderstorms than we normally do and many have occurred on weekends which seems to be causing some excitement and issues. I was caught slightly off guard a week ago when a front went through with maybe 25 gusting 30 for 20 minutes so I thought it was over and then 3 hours later, we had 30 gusting 40 for half an hour with nothing showing on the radar and no predictions although the clouds did give some hint.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Thanks for the fill on that. Really interesting and confirms that a they took a lot of unnecessary risk, particularly since, as I suspected, it was short lived. And I like all of the options you suggest way better than what they actually did.

I think one of the problems here is that the weather forecasts these days portray thunder storms as far more dangerous than they really are so people are programmed to get into harbour at all costs: https://www.morganscloud.com/2009/02/01/radio-fear/

Like you we have simply held station through several thunderstorms over the years and been none the worse for it and a great deal safer than getting close to the hard stuff in driving rain and low visibility.

Hey, John. Thanks for this and it reminds me why I don’t read things like this. Way too much bravado in this article for me (which has the tendency to easily mislead a novice like myself). I had a bunch of squalls this summer around The Baltic (which can be very squally at times) and found myself with a totally inexperienced crew in a squall when just about to turn toward the harbor. A couple of the stories at the beginning of Heavy Weather Sailing sprang to mind and I calmly and firmly said to the crew, we will stay out till this is over, and they all agreed and that was that. In fact, everyone had the time to quite enjoy the spectacle of it all with no pressure (even me). There was no danger sitting out the squall but there would have been plenty trying to tie up in a small harbor with an inexperienced crew.

Hi Michael,

I agree that the prose is, shall we say, a little lurid and therefore can be misleading.

And good on you for keeping cool and making the right call, particularly impressive given that you are comparatively new to sailing. Shows that good seamanship and experience are not necessarily correlated.

We had a similar situation last week. A squall line and cold front were approaching fast; we reefed the main to 2nd and the #3 jib to half just as the rain hit. The wind shot up to 20-25 knots a couple of minutes later. The waves had only had time to build to about 4 feet, nothing serious, but visibility dropped to about a mile and the boat was whipping along on a beam reach, happy as a clam, at 8 to 9 knots. Which would put us in an anchorage we hadn’t seen from that angle in nine years, without good visual references, and with a rapidly veering force 6 nor-wester of uncertain duration and eventual direction.

So, after consulting the Sail Canada examiner we had on board for the week, we simply tacked through 180° and hove to for half an hour. No real danger. We got to watch the frontal system evolve and pass. Then, as the rain cleared and the north wind stabilized, we had a clear and comfortable shot into the anchorage that, 30 minutes earlier, was a jumbled rain-hidden mess.

This has been, for me, the hardest part of moving from little boats to big ones. Aboard my Bolger Diablo 15 and my mom’s Doral 19, the best heavy weather strategy is almost always to open the throttle and shoot the inlet, trusting that 90+ HP per ton will get you to a pier ahead of the storm. But our C&C 35-2, like most larger sailboats, is totally happy to just wait in her natural aquatic habitat until the conditions are right to bring her into the riskier near-shore regions.