In the first chapter on coming alongside in current in this Online Book, we explored how current has very different effects on close-quarters boat handling than wind.

And, in Part 2, we learned how to turn our boats in confined spaces in current and then added wind.

Now let’s look at backing into a tight situation where there is no room to turn around. And let’s make it even more of a giggle by adding some final approach and line-handling detail—more of that stuff coming in Part 4.

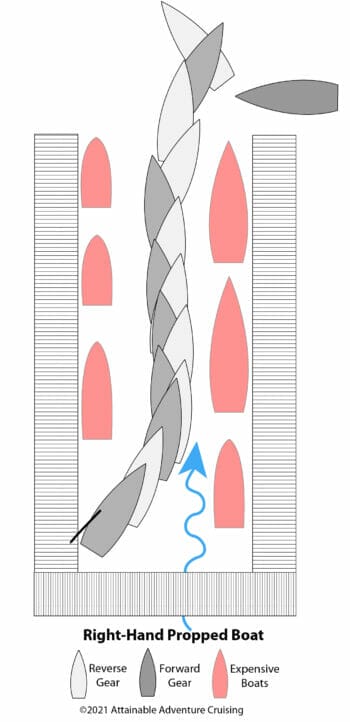

Once again, we will be applying what we have already learned in this Online Book about backing our boat and then factor in the current.

John, would you recommend practising these maneuvers, say, on the side of a wharf with current but few if any boats? We have maneuvered in variable conditions next to the more benign type of plastic buoys just to get a sense of what a cross wind will do to our attempts to keep station. This has suggested to us which “stupid boat tricks” are either beyond our skill sets or beyond our boat to safely accomplish, particularly in tight situations. You have to know when to fold ’em!

Hi Marc,

Sure, any practice is good practice.

John, I would be tempted to elevate the next to last point in the summary to the top: always at all times have an escape route. Also, I make it a rule that any crew member (not only the helmsperson) can call for a go-around and that go-around is immediately executed without discussion. The reason for the call can be discussed later when in open water.

Hi Alex,

I agree, that’s the most important point, that was why I have it bold, but putting at the top would work too.

As to crew calling a go around, that’s an interesting one but I have to say I’m ambivalent about it. I can see you reasoning, but on the other hand I think it’s really important that only one person be in charge (does not have to be the person at the helm), particularly in close quarters. Hum, I think on balance I prefer not to muddy the waters by giving everyone on the boat a veto.

Hi John,

this is something I have picked up from reading way too much about aviation industry and air accident investigations. As far as I know, it is SOP in all of aviation that both pilot flying and pilot monitoring can call for a go-around and that call is never penalized.

The other crew member may see something that the helmsperson does not see and in close quarters there is probably no time for a discussion.

Even if a crew member simply does not feel he can safely execute their job (e.g. step off onto the dock), I’d rather have a talk about that in the open water than pressuring them into endangering themselves. Hence, I repeat on each approach briefing that “You can always go around“

When backing off a mooring, I rely on my wife and/or son at the bow to not only confirm that we are “off”, but also to let me know when we are clear of the trailing moorings/tender and I can turn to one side or another. I usually suggest my preferred actions prior to unmooring. We have found this helpful. Experience has given everyone involved the sense to keep quiet unless there is an obvious danger or concern.

Coming alongside on port (my preferred side due to favourable prop walk but the side with reduced visibility when I am helming from inside the pilothouse), I usually ask how my docking estimations went. It never hurts to see if one’s visualizations reflect reality.

Hi Alex,

As I said I’m ambivalent about it, but do keep in mind a copilot is a fully trained pilot. This is most often not the case on recreational boats. In fact I would argue that letting many crew order a go around would be analogous to letting the chief flight attendant order a go around on a plane.

That said, a crew should feel free to report something they see as well as refuse to put themselves in danger, at any time.

John, that’s a funny analogy. I’ll have to rethink my SOPs next time I’ll have someone from outside my family as crew.

Hi John and Alex,

For me, the issue comes down to timing. Anticipating a proposed plan of say, taking a shortcut that takes one near shallower water or rocks, vs staying outside in deeper “safer” water: either of us has veto over the “riskier” plan. But once in the midst of a maneuver, the skipper calls the shots. We habitually, after a questionable event or when things go pear shaped, try to have a bit of a “formal” sit down post-mortem where we look at what went awry, what went well, and what we could have done differently.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

We do something similar. I think of it as the difference between strategic and tactical situations.

This is a good idea, of course, but many crew skip the “what went well” post-mortem. If I spot improvement, or am spotted improving, it’s a positive thing to point out.

To me it depends on the experience of the crew member. I would listen much more to someone with experience in doing the maneuver. Not so much to someone who had not.

Hi Edward,

Of course, that’s true. And I’m absolutely in favour of a crew member speaking up if they see a problem. But we also have to be careful about encouraging too much chatter, which can be dangerously distracting when executing a tricky manoeuvre. Generally, very little talking is a sure sign of an expert crew.

Hi John,

I know some crews are wedded to their communication headsets, but I have never been a fan for just the reasons you mention (as well as the fiddling sometimes necessary to keep them working properly and in place on one’s head when working) at least for the size boats we are generally talking about.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

I have always felt the same, even on our 56 foot McCurdy and Rhodes. Hand signals can also take the place of a lot of chatter.

Hi John, Interesting article as always, But surely it is easier to back towards the current, then the bow just hangs idle? In cases of backing with the current, and current is strongish – the chance of the boat pivoting round is more present, thus more risky ? – and backing towards the current – it is easy to stop once you have reached the desired position (keeping a light reverse) whilst moring? – ie and as you state, if things go wrong it is easier to motor out. – Thanks for interesting articles – Best regards from Norway – Colin

Hi Colin,

That’s certainly intuitive, but in fact whether we are backing into the current or stemming it makes no difference to how the boat pivots. See part 1: https://www.morganscloud.com/2021/10/27/going-alongside-docking-in-current-part-1/

That said, you are right that holding the boat in reverse can work, but if any wind pivots the boat, we then have to go into forward to fix that, and then we are going like hell before we know it.

Hi John,

I got shivers of dread in a number of your described scenarios.

Slight typo in 2nd-to-last blue box:

“This property of current becomes a big factor when dealing with situations where the current is running across floating docks, since the hulls of the boats moored to the up-current side will create lulls in the current, but the gaps between the boats will actually accelerate the it.”

Hi Alissa,

Writing it had the same effect on me! Thanks for the catch, fixed now.

Far be it for me to be critical, I’m hopeless at motoring backwards at the best of times. Especially given my prop-wash changes according to my boat speed, but……. I’m struggling to understand why you would ever want or need to back against a current. Certainly manoeuvring in a current is one situation when it is better to postpone any additional difficulty to tomorrow after you have had a good night’s sleep. A boat will sit better moored into a current, and it won’t be inclined to collect all the crap that often accompanies a current. (You know, bottles that go donk in the night). As for reversing into a berth Med style I never do it- pointing your delicate bits into the unknown is just too frightening. I mean, have you seen what gets dumped into the water there? Shopping trollies ain’t in it, I’ve seen a car lurking there, just below water level. Not to mention silting. And getting out of trouble, for me, it’s always better to be motoring into a current when you can be going slowly and gently.

Hi Mark,

Each to their own. My thinking is that by going in forward and deferring the problem until tomorrow, we could very easily get ourselves into an intractable situation. That thought will interfere with my sleep a lot more than just dealing with it up front.

Also the big advantage of backing in is that we can always blow it off. Once we go in forward there is no way out that does not involve backing, so it’s just as well to perfect that skill. More on how to do that here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2018/01/19/coming-alongside-docking-backing-in-part-1/

Also, if we will never back in, what about the opposite situation where the current is inward flowing?

And note that I make clear that backing up-current is a tricky one that I don’t recommend in strong current situations, so perhaps we are more of the same thinking than it might first appear.

As to underwater obstructions, I hear you but we are generally dealing with well used berths here, so not really an issue. If I had any doubts at all about that I would be anchoring out and scoping it out in the dinghy before trying it. More on that in the next article.