In the last chapter I covered the basics of backing in to a tight space to come alongside:

- A boat is not a car.

- You gotta come ahead to go back.

In this chapter I’m going to cover the all-important approach, and then provide four step-by-step recipes (complete with diagrams), one for each wind direction. And then we have a video to tie it all together.

But before we dive into the details, I’m guessing that many of you are going to get halfway through this chapter and start thinking:

I’m never going to remember all this in the heat of the moment.

Added to that, every approach situation is different, so while I’m going to give detailed instructions for each wind direction, you will need to tweak things on the fly to match the exact situation and your boat.

It’s Not That Hard

So here’s a bit of reassurance:

Learning to back in to tight spaces is a lot easier than it looks at first glance, because we don’t have to get the approach right the first time. As long as we watch for one potential gotcha (more on that in a minute) we can always blow it off by going out forwards and coming around again—one of the great advantages of a back-in docking.

I have been doing back-in approaches with the same boat for a quarter of a century, and we still make two or more approaches about a quarter of the time. In fact, we often make a first approach purely as a reconnaissance to check the conditions.

Given that, rather than trying to commit the rest of this chapter to memory and then applying it, I recommend reading it through and then going out on your boat and trying a few back-in approaches—preferably in less than 10 knots of wind—and then reading it through again. Once we have actually tried this in the real world the theory will become a lot clearer.

Bystanders

So given that we may go around at least once and maybe several times, what about the dock guy and all the other know-it-alls on the wharf yelling instructions at us?

Look, after reading this Online Book to this point, even the most inexperienced of us knows far more about what we are doing than they do. So just remember that. It makes it easier to tune out the noise.

The other cool trick is to cup your hand behind your ear and then shake your head in a pretence of being deaf. (It’s not a total pretence in my case.) Makes ’em crazy, and they give up and stomp off, leaving us in peace to get the job done.

Know When To Walk Away*

The reason is that the only way to get straightened out (as we learned in the last chapter) is to go ahead, so if we get into a situation where there is no room to do that we are…let’s see if I can put this politely…screwed.

Once again, the key thing to remember is that there is no shame in motoring out to try again—if in doubt, blow it off.

OK, with all that out of the way, let’s get started.

Close Approach

A good back-in docking starts with a good close approach.

My boat’s prop (RH) is aft of the rudder and so I don’t get to use prop wash against the rudder to assist. Do I need to vary anything in the instructions in this book?

Excellent article John,

In response to David, is the prop close enough to the rudder to be able to use prop wash in reverse ? It would be interesting to see how that works in practice.

What boat is it ? Is is an Albin Vega, (one of the few boats I know with such a setup).

Regards

Patrick

The boat is a Robb 37. The propeller is on the centre line.

David, having the prop behind the rudder mens you have no propwash at all, the rudder will only work if the boat is moving above a hopefully low threshold speed. Maneuvers such as using a burst of forward while going back will simply make the boat slower and thus reduce any ruder effect any more.

Not the easiest setup and I assume the only remedy is to be as bold as you can be and always have enough speed in the boat so the rudder is effective. As long as you have speed you can always idle out the engine to momentarily kill any propwash, if necessary.

HI David,

Hum, well I’m pretty sure the instructions in this chapter and the last won’t work for you. So then the question becomes, as Patrick writes, what will work? Assuming the prop is on centre line, I think you might be able to use the prop wash with a hard burst of reverse to kick the stern back and forth. The only way to know for sure is going to be to experiment in open water and then slowly move into more confined spaces.

I can’t tell if you photoshopped out “dock hands” at the end. It looks like your First Mate throws the dock line onto the dock, and then, I suppose, she must step off when you get close enough, since that part is not shown. Is that what you customarily do? I have my first mate step off the boat WITH the dock line in her hand. If she can’t step off, I haven’t gotten close enough.

Hi Glen,

I edit these videos down so they just make the point of a given chapter since their a few things more boring than an under edited video. You can see the actual docking and Phyllis stepping ashore in the video in this chapter from the same clip. That chapter also explains why she throws the line ashore first.

As to dock hands, three helpful people came down to the wharf to take a line, but each time we explained, as politely as we could, that we did not want help—these pesky Atlantic Canadians, just too nice. I just edited the video as much as I could to get rid of that extraneous stuff. (At least with my limited skills, there is no way to “photoshop out” anything in video.)

Hi John,

A really nice tutorial. A long straight wharf or dock, if empty, can make a great practice area. Just go back and forth in reverse keeping the same distance off and practice the described maneuvers.

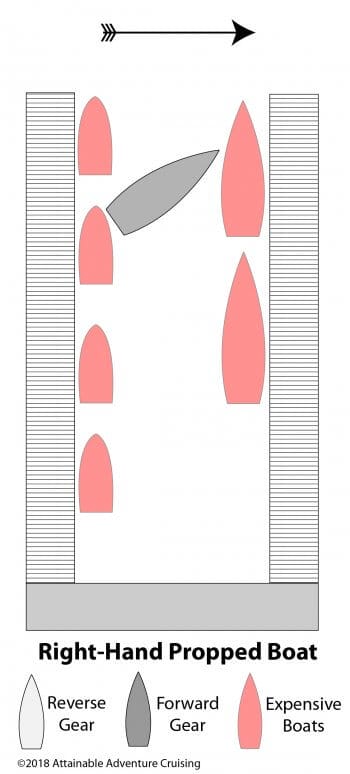

When it comes to other boats around, I know you have said it before, but prior preparation can/will save a world of embarrassment/anxiety. When there are expensive vessels with buff guys are on both sides of your boat, having fenders well distributed on both sides of the boat (this is where the US vessels habit of only carrying 4 fenders becomes problematic) and docklines in place ready to go will save much distracting running around.

I am also always ready to raft (whether the buff guy likes it or not and all those expensive boats in the diagram should have fenders out or I will feel less sorry for them) as when things start to go pear shaped (big gust of wind gets you cross wise) it can be very hard to extricate without going bump. A quick tie up can get you settled and straightened out and on your way. To facilitate this, I often have a midships line ready on the side opposite to the side I expect to tie onto.

Some fat inflatable fenders can be a topsides-saver. We frequently have a mobile one that Ginger can move and position with speed and ease because it is so light.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

Yes, I agree, most boats don’t have enough fenders. Also, good point about the lightness, and therefore ease of handling, of the new(ish) big inflatable fenders. I had not thought of that advantage.

Hi John,

I have really enjoyed this series of articles and one or two tips have become our new standard practice, so nice work thanks.

A couple of thoughts from a yacht with no bow thruster and a high clipper bow that takes over in cross-winds over 20 knots. In these conditions, Bonnie Lass is let’s say, reluctant to being straightened out. Even by maniacal use of the throttle, the bows just want to blow off the moment we loose way and we generally end up crabbing ungracefully across the wind, backwards and forwards. Luckily, we steer and mostly track very nicely in astern with way on, albeit somewhat crustacean like in strong wind. Most of our cruising avoids marinas and docks like the plague infested holes of old (hence no bow thruster) so our main practise is approaching our own berth which is usually up or downwind.

However, the annual haul-out / inspection almost always manages to coincide with cross-winds, a gale warning and rain. The last vestige of sun usually departs as we let-go, heading stern first for our date with the unforgiving concrete columns of the travel lift dock. Then as the first squalls come whistling across the water and the noise of the rain reduces communication to a well known but hardly nautical hand signal from my long suffering first mate, we know we can’t go slow or we loose the bow, so for us “re-adjustment” is a full bail-out, try again. From experience, we have learnt to limit as much other wind resistance forward of the mast as possible – we ensure our jib is tightly rolled on the forestay by keeping more than usual resistance on the sheet whilst furling (this can halve the windage over a loose roll). Then we further roll the jib wrapping the jib sheets until they are close to deck level, take all the forward halyards to the mast, of course the anchor locker lid is closed and we even have the bow crew stand at the mast until needed.

If the wind is gusting over 25 knots cross-wind we take the jib off the bow, and I am not too proud to call our dock-master well in advance and ask him to be on stand-bye for a helping nudge, should the bows be caught as our stern enters the dock. I have found that almost all marina dock masters (including ours) are actually very skilful at assisting if you only ask. I have never experienced scorn for a skipper with a largish yacht (ours is 47.5 feet) that asks for help in good time, when the wind is up (especially when you explain you don’t have a bow thruster but do have a bow that likes to assume command). Anyway, they are usually fellow boaties and like an excuse to get out of the office, even if it is pouring with rain and blowing dogs off chains.

Rob

Hi Rob,

Very good tip about reducing windage forward, thanks.

Brilliant

Clear and concise

Hi David,

Thanks very much for the kind words, makes the hard work of putting a chapter like this together worth while.

Hi john,

great series.

Not sure if you have seen the videos produced by Maryland School of sailing. This one, although in benign conditions shows both the standing turn/pivot turn / back and fill technique. Along with reversing in all the way with the wheel over hard to starboard and using only prop walk and prop wash to steer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qOPM_SMJCc

Hi Garry,

Yes, I have seen the Maryland School of sailing videos before, although not that one, and they do a great job. That said, I think we also need text and diagrams to really understand the fundamentals although I’m sure MSS do that (probably on a blackboard) in their hands on courses.

My one criticism is that I don’t like seeing people handling loaded springs in their hands like that. Yes you can get away with it in flat calm on a 30′ boat, but it’s still a dangerous habit to get into, particularly since a boat of just 40 feet will be over double the weight and windage.

All loaded, or potentially loaded, docking lines should be around a winch, or cleat.

Hi John,

As to your rule (If you can’t go in backwards, then do not go in forwards), I basically agree, but you must have alternatives. I have experienced a number of times where I felt damage would likely occur were I to proceed in backwards and that I had little choice (only marina, no anchoring, late in day and dozens of miles from an alternative), but to go in forward. The plus side of going in forward is that you get secured and can stay safe until you figure how to get out in a safe manner. Being safe and secure at the end of a long day with night approaching is no small thing.

If you are lucky, the afternoon winds that made things difficult the previous afternoon will die down and make for a calm morning and easier exit. If the exit proves difficult, a consideration less used than it should be is to warp out. If I say to the buff guys on the expensive yachts moored around me that I intend to leave, have no bow thruster and really want not to hurt their boats, I have always gotten help. And again, I would not hesitate to raft, and do it well before you get crosswise. Who knows, they may be serving a good breakfast. Usually it is a combo of warping, rafting and powering that can get one to open water.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Thanks for the article and info. I look forward to getting Prosecco wet in the spring (she’s on her cradle at East River Marine) and trying out the techniques. My dock slip is so easy to enter and exit (no current, minimal winds, straight approach) that I’ve not been forced to learn any of these techniques yet.

Purely from a theoretical perspective, as I don’t have the hands on experience I do have a question about the “don’t go in forwards” rule. You mention the hardest condition for a RH prop boat is to back in with the wind coming over the port side. But – if in that situation you drove the boat in bow first, and wanted to bail out you could then back out of the fairway — now having the wind coming over your starboard side (because you didn’t turn around) which means the wind would be simplifying the process of reversing the boat, in this case backwards out of the fairway.

Maybe easier than fighting to go in backwards? Of course it presumes you are comfortable backing the boat out.

Mark

CS 30 Prosecco

Hi Mark,

Sure you could do that, and good on you for figuring out that in that circumstance it will be easier to back out. That said, if it’s blowing hard enough to make it impossible to go in backward I’m always nervous about going in forward because if I do make mess of it, bailing out backwards, particularly after a screw up, is just intrinsically more difficult.

Of course, if it’s just a piling berth we are talking about, with clear water immediately outside of it, I would be a lot less worried about going in forward.

Keep an eye out for me in the spring at East River, it would be fun to meet.

John,

I was down at East River today adding some supports to my canvas frame while I looked longingly at the sheds. I imagine it’s a lot nicer in there than it is sitting 50′ from the breakwater!

I look forward to experimenting with backing in. I have a lot to learn. My CS30 (just a coastal cruiser and not a voyaging boat) seems to have minimal prop walk but I haven’t tried backing her in.

Hope we hit the yard at the same time in the spring – it would be nice to meet face to face.

BTW – zero offense taken here – I was merely pointing out an interesting exception on the rule. If conditions are hairy then better not to stick your nose too deep and discover there is limited options – but if you “need” to get in then the right wind conditions make it easier to back out than to back in.

Mark

Hi Mark,

Yes, being inside is pretty nice, although cheap it’s not! I will be at the boat a bunch starting in March, so I will keep an eye out for you.

Hi John,

I’m with Dick about the exception to the “forwards rule” Conditions change, and if I can get tied to the dock by going forward while fighting extreme wind or tidal current conditions I’ll happily figure out how to get off tomorrow when conditions have eased.

Great series about boat handling on the kind of boat us old codgers learned on. Most of your readers who have full keel boats or ones with large skegs have figured out how to maneuver their boats through years of practice— your descriptions and diagrams just put it in a more concise manner. However might I suggest that the boat owners who most need guidance are those new to sailing or to handling a cruising-sized boat. They will find your chapters not very applicable if they have bought a new boat in the past 10 years because their boats lack one or two of the tools you use for boat handling. If they have twin rudders prop wash will be ineffective. Folding props or props hidden behind the keel— not much in the way of prop walk. And in places like the Caribbean over half of new boats are catamarans with high windage and atrophied keels, but twin engines and props.

Maybe you should write a separate chapter about docking”new boats that drive like cars” LOL The Frers Swan 54 owner that I babysat up from St. John to Annapolis could have used it!

Hi Richard,

Actually, I don’t think I have waisted a couple of hundred hours (I hope) preaching to those who already know. In fact I started this book after seeing many very experiences cruisers who had owned their boats for years having trouble docking, or turning their boats.

And the base techniques and understanding will still help those that have fin-skeg boats that do back in since even with those we often get into situations where kicking the stern one way or another with a burst in forward is vital.

As to boats with twin rudders, I addressed that here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2017/11/16/qa-coming-alongside-docking-with-twin-rudders/

Hi Dick, Richard and Mark,

Please note that what I wrote was “Our usual rule is that if we can’t get in backwards, we’re not going in forwards.” The key word being usual. Sure there are times when we go in forwards. Nothing is these chapters, or most anything else I write, should be taken as engraved in stone.

Boat’s are different, situations are different, and skipper’s skills vary. I get that. It’s impossible to cover every eventuality in a book like this. My goal is to give readers the base skills so they can deal with many situations.

Hi John,

My apologies for any lack of clarity. My intention was in no way to challenge your guidelines: there are always exceptions. And I was clear that I agreed.

My purpose was more along the lines of suggesting safe alternatives in the face of an anxious maneuver that may not be readily thought of. (I believe that anxiety makes most of us stupid: certainly that is the case for me). The alternatives I had in mind were the possibilities for warping in or out as this usually maintains good control over the vessel. The other was rafting where one can get sorted and start afresh if things go a little pear shaped.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick,

Nothing for you to apologize for. Rather, I have to admit that Richard’s comment suggesting that I had basically wasted a huge amount of my time and creativity on writing this online book, or at least these two chapters, put me in a cranky frame of mind and then I took it out on you and Mark in the form of a rather stifle worded comment, so I’m the one that owes you both an apology, sorry…Richard had it coming…LOL.

Hi John,

Lighten up, mon.

If somebody is looking for a way to be pissed off they can always find a way. Like deciding that they are being accused of foolishly wasting 200 hours when somebody praises their work and suggests that an additional chapter about boat handling of contemporary designs that respond differently would be useful.

Now I am the one pissed off. I think I’ll take a break from your site for a few months.

Hi Richard,

Your call, but I was joking. :-). And yes, this project has definitely made me way too sensitive, so my bad there.

Hi Richard,

And 200 hours was almost certainly an exaggeration, I have to say I have lost count.

Having regard to a home berth, there is a lot to like about a swing mooring and a good tender. My home marina is really not that difficult although it is worrysome when the wind is pushing above 15-20 knots, especially when single-handed. I berth forwards to a finger jetty on the starboard side and I have a RH prop. When berthing with the wind, I need to stop the boat with reverse thrust and that sends me away from the jetty! I have a CLC pram dinghy on order. My intention is to build that dinghy, then move onto a swing mooring.

Hi David,

As you say, there’s a lot to like about a free swing mooring, not the least being that a good mooring is, depending on exposure, generally safer for the boat in a blow than a wharf.

As to you issue about being blown off your wharf. How about permanently rigging an aft running spring on the wharf? You could then pick it up with a boat hook and then power against it to come back into the wharf, pretty much no matter the wind. More here on aft running balance point springs: https://www.morganscloud.com/2017/03/29/coming-alongside-docking-in-4-easy-steps/

Hi David,

you can help to keep your boat straight when going astern, if you still have some forward way on, by turning the helm into the direction of your prop walk, ie to port in your case. You will need a bit of practice to see how much helm you require, on my yacht it is basically hard over.

Nice work, John. Thank you.

Thanks, Mark

A quick note to say thank you for the post. Our boat is a 1982 Sparksman and Stephens designed Stevens 47 with a similar underbody shape to Morgan’s Cloud and reversing into marinas is always a challenge especially where it seems everybody else in New Zealand is in a modern fin keeler Hanse with a bow thruster … After my wife and I read the post and watched the video we agreed we needed to practice the technique somewhere safe but like many good ideas we did not get around to it … Sure enough today we were backing out of a slip after a short maintenance period and got ourselves a bit stuck trying to counter the prop walk, the current and the wind conspiring against us … it was great to have a new tool in the toolbox to get out safely. Still intend to to practice the skill somewhere safer but even better hope to avoid marinas for a few more months.

Interesting this is not covered in any text I have read or training curriculum I have taken or taught (I used to teach sailing in Halifax near your home base).

Much thanks,

Max

SV Fluenta

Hi Max,

Thanks so much for the kind words. These posts are a huge amount of work, so it really means a lot to me to hear that they have actually helped a member out there cruising. By the way, the Stevens 47 is a great boat. I raced (bow man) against the prototype, skippered by Rod Stephens, at Antigua Race week back when the world was young…we didn’t win.

Hi John,

An excellent series of articles. Worth their weight in gold. Thanks!

Hi Norris,

Thanks for the kind words, much appreciated. There will, I think, be more chapters over the next few months.

Newbie question: Why not use the dinghy and its engine as a tugboat? I googled this just now, but apparently google thinks no one has ever tried this.

Hi Ben,

I believe you might try this if you have (a) a dinghi with more than the usual 2.5-5hp, and (b) no wind and no current, and no choppy waves.

Joking aside I doubt that a dinghy as used with the yachties would be able to counteract the forces of wind or current – and if you’re shorthanded you would be even shorter when one guy sits in the boat.

Hi Ernest and Ben,

Using one’s dinghy as a yawl boat can be very effective. My previous boat was 38 feet and had gremlins residing in the engine. For a couple of seasons, we became far too experienced at strapping our inflatable to the hip and using the 6hp outboard for propulsion. Our cruising grounds at the time generally had flat calm mornings and it was amazing how easy the larger boat moved: 6 kn boat speed was easy to achieve and excellent maneuverability if someone was in the dinghy using its engine to steer. However, it did not take much wind or seas to make all controlled movement far more problematic.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Ben,

There are certainly times when having someone in the dinghy, assuming you have enough crew, to give the bow a push can be useful.

That said, the problem is that the props on dinghy outboards are pitched very coarsely for planing. The result is that said prop provides very poor thrust when near stationary (bollard pull). I once tried to help an 80-foot boat get off a dock in an onshore breeze by pulling the bow off with his tender (big RIB). Even though the outboard was quite a big one we had no luck at all for just this reason.

Hi Ben,

Using the tender as a little tug is a very common technique on a lot of schooners in the 50-150′ foot range and I can’t say that I really like it. Having worked on some of these boats a fair bit and trying it with both tenders, yawl boats and little tugs, a good boat handler can do 99%+ of the dockings required safely without this on that size boat which are much harder to handle than cruising boats. Using the tender requires launching it and losing 1-2 crew to it. Then, it takes very well rehearsed communication and someone in charge who understands momentum well to even make it work. Even with this, it is often not that safe for the people in the dinghy, especially if you are towing instead of pushing as tenders don’t tend to have good tow points. And all of this is very time consuming and not very fun and the whole point of what we do is to have fun.

John is right that pushing force is an issue. A dinghy with a 10hp has plenty of power for most cruising boats in most weather but can’t put it down due to the prop design and depth underwater. You have plenty of force in light air but then you probably don’t need the help and then when it really pipes up, you don’t have enough force. If you look at the design for yawl boats, they will often have 50-150 hp (some are 200 hp+), but will swing props that are 20″+ not the 8″ one on your tender and they still struggle, especially with reverse.

Sure, it is handy in super rare circumstances but it isn’t useful then unless you have practiced it so overall, I just think that getting good at boat handling and then planning bailout options well means that it is an unnecessary hassle. Despite being practiced on larger boats, I have never done it on a cruising boat and never actually felt the need. That said, while I only employed it on those vessels extremely sparingly after doing it a fair amount as I was learning those vessels, a lot of them use it all the time or much of the time so some people really feel it is the right thing to do, just not me. If you need max maneuverability, nothing beats a few tugs and/or thrusters and pod drives but I find it very rare that you need that on a vessel the size of most of ours.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Good point on the safely issue. I should have covered that. Thanks.

Great set of articles, putting it all in an easy to understand way. I’ve tried it out on my boat, a Warrior 40 which has a long fin keel, skeg and high bows. All good except for the reversing with wind coming from the starboard (difficult) side (left hand prop) in about 15kts wind albeit out in the open by a line of empty mooring bouys. I found that when in reverse the bow blew off much faster than it would go back into wind when going forward, so the net result was by the time I had the bow pointing where I wanted it I was going forward at an appreciable speed so when I then engaged reverse it took a while to get going backwards and by that time the bow was way off downwind again and I was back where I started or actually a bit further forward rather than back where I was trying to go! Any suggestions? The only partial solution I found was to start off bow into wind before engaging reverse so by the time the bow blew off 90 deg I’d got up to 2-3kts sternway and by then had enough steerage to keep going in the direction I wanted but faster than I would want to be approaching confined space with expensive boats in a blow.

Hi Bruce,

First off, there are situations for given boats that simply don’t work if the prop walk is on the difficult side, so this may just be the way it is with your boat, but the good news is that you now know that and so will avoid that situation and resulting trouble.

The other thought is that you may simply not be using enough throttle. With that much wind you may need to be quite aggressive, all the way up to WOT in a burst, particularly if the engine is small. Other possibilities are a poorly sized and or pitched prop, or a folding prop. If you advise the engine, reduction gear and what prop you have, I may be able to at least guess at the problem.

And finally, good on you for getting out there and practising. I would venture to guess that less than 10% of boat owners ever do that.

Hi John,

Thanks for the reply. The engine is a volvo MD22L 50HP, gear ratio of 2.2, sail drive and a Darglow Featherstream 19×14 3 blade prop which is slightly overpropped on Darglow’s advice. I was kind of thinking like you said that maybe it was just a situation that just doesn’t work but was wondering if there was something I was missing. I’ll try again with more throttle but from what I recall I was using quite a lot (it was end of last season but only just got round to posting the question!) The boat does have a bow thruster which wasn’t working then due to charging issue with the battery which I’ve subsequently fixed, so I have that to help in difficult situations but I’d prefer to learn to manoeuver without it wherever possible and not come to rely on it.

Cheers,

Bruce

Hi Bruce,

Very good call not to become too dependant on the thruster.

Do give it a try with more throttle. I guess a good rule of thumb is if it feels like the right amount of throttle, it’s probably not enough! The key point being that you need a short, but powerful burst, not a longer and less powerful one. Given that WOT is 3000 on that engine you might easy need to go to 2500 rpm on each burst if there is breeze. That’s still only ~30 hp at the prop.

Here in the med, I’m very anxious when parked bow-first to the pier and there are a left and right mooring with my boat which has a prominent prop-walk. The situation looks like this: https://i.postimg.cc/wyt74g1N/parked.jpg

The problem is that more or less in line with the boat is a block underwater tethering the mooring for the boats to the left and right. Often enough, those blocks a set in a way that I have about a boat-width of free space for the bottom of my keel.

I’m always afraid to catch one of the neighbouring moorings, specially the port one with my keel. I have to admit, the fear isn’t only theoretical, I got caught in them a few times. I don’t seem to be the only one challenged either as I helped a few other skippers to untangle their boats.

Does anyone have a good suggestion how reverse out in this situation without mishap?

Hi Joe,

Great question, I started to answer is as a comment but it got too long, so I will tackle it in a short post.

Can I have permission to use your diagram?

Hello John,

Sure, I’d be happy if you use the diagram. That’s why I made it. I attached it to a mail Phyllis replied to.

Thank you

By the way, I got quite proficient at untangling keels or saildrives from moorings.

What worked best for me even single handed was:

1 Run a line to any other boat or a mooring. Just to be safe. Add a fender or two if other boats are involved.

2 Calm down

3 Shut the engine down

4 Dive to find out what really happened

5 Untangle the mess.

What never worked for me: Motor around or shout

I might try using the windward mooring to pull the boat out of the slip with the engine in idle, and reversing out not before my prop is free of the neighbours’ moorings.

Hi Jo,

We have used variations on the below when we have been in similar situations.

Find someone with a dinghy (or the marina’s yawl boat) with a decently sized engine to pull you out while you fend off: no guarantees not to get blown off a bit, but better control is likely and no prop wrap/motion to worry about. Those with bigger dinghies are often gung-ho to help. The marina usually helps as they want these things to go smoothly with no damage to their guests.

The next is to engage the skippers on either side (self-protection for them) to put a little weight on their stern lines on your side and sink them down below keel depth. This will also cause the boats to fall off away from you giving a bit more room. You should reverse out with a bit of power pretty straight and when prop wash kicks in you should be clear of the stern lines.

Cross winds, of course, makes all more challenging.

Good luck, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hello Dick,

Thank you for the reply. Most of the time, those things solve the problem. If I have trustworthy crew, or the marineros are around, this makes it a lot easier. The lesson I learned is that sometimes it’s best to ask for help.

With little wind it’s often just enough to pull my bow port close to the neighbour so that the propwalk straightens the boat first.

Hi Jo,

You are welcome.

And agree, motoring around and shouting has never worked for me either.

And agree, for me, it is sometimes best to ask for help, especially if the help can be well directed (unlike the help that is offered when approaching a dock).

And agree, with no wind these questions often disappear. When the wind is predictably calm early, I have been known to set an alarm and depart at dawn (no audience then either) and go pick up a mooring or anchor and have a calm breakfast with the anxious task of the day accomplished.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Actually around here in the med, most mornings the water is flat like a mirror. I think I’ll adopt this policy of leaving at sunrise and having breakfast at anchor. It makes setting sails also a lot easier single handed and sail off the anchor when the wind wakes.

Seems I still have a lot to learn about taking it slowly and making my life easier.

Thank you, Dick. This is the kind of simple comments everyone takes for granted, but very helpful for newbies like me who never thought about it this way.

Hi Jo, The pleasure is mine, especially after receiving such a nice note. Dick