In Part 1 we looked at how the effects of current differ from wind (a lot) and four simple cases.

Now let’s look at some more difficult docking situations in current and confined spaces, and how we can still get alongside safely.

Our goals for this chapter and the next are:

- To build the fundamental skills to handle all the different situations we will be faced with in the real world, rather than try to cover every possible scenario, which would be impossible with all the variables in play.

- To learn how to identify docking-in-current situations that are a disaster waiting to happen, no matter what we do.

- To not get distracted by the details of the final approach and getting lines on the dock. We touched on that in Part 1 and will dig into it more deeply in Part 4.

In and Turn

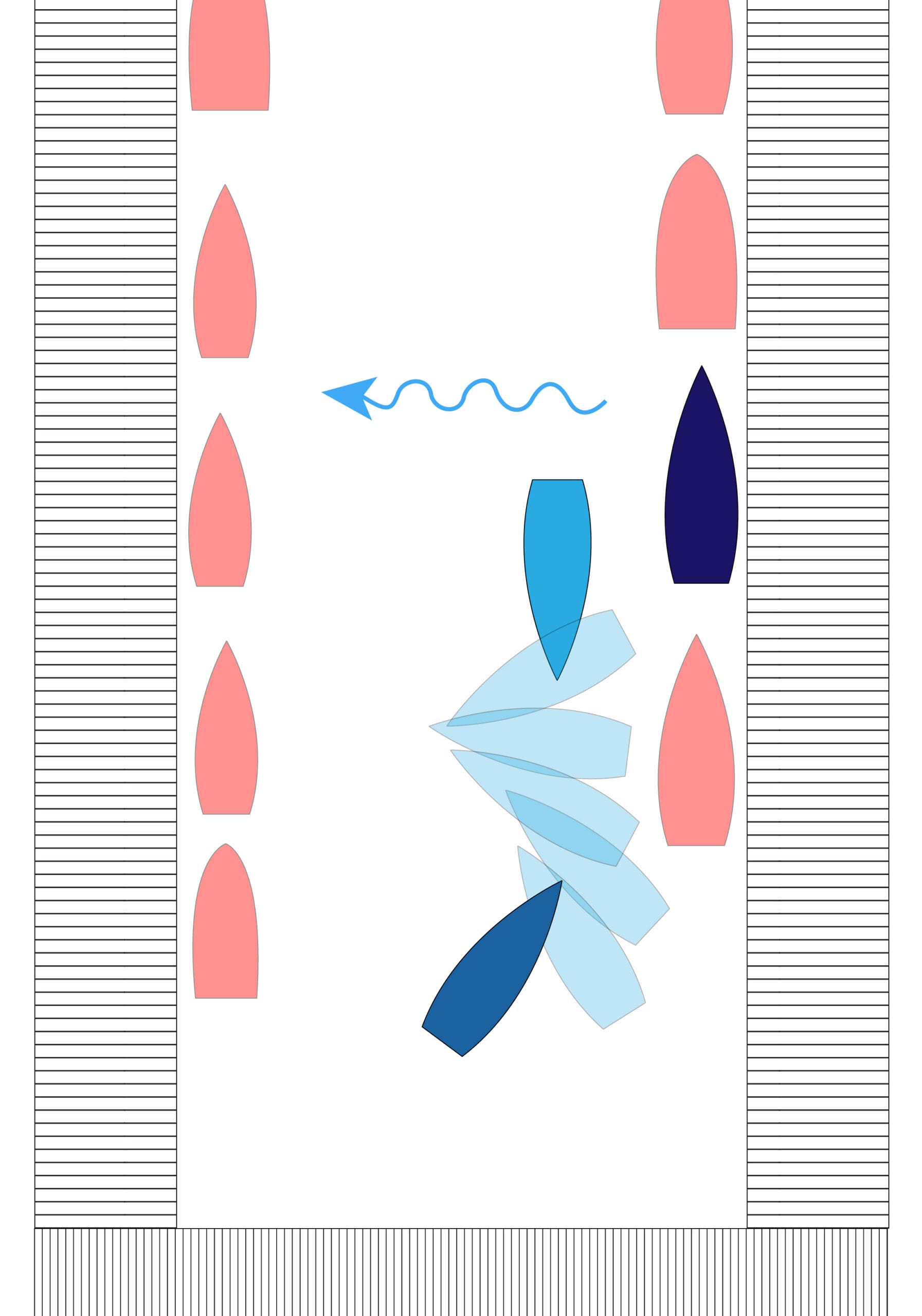

To start off, imagine the berth we have been allocated is halfway down one of two parallel floating docks placed two boat lengths apart.

This is one Phyllis and I know well having spent two winters inside the Mega Dock at Charleston City Marina.

Given the distance we will have to cover from open water to the vicinity of our berth, the best strategy is generally to motor in forward, turn the boat, and then dock bow out to make it easier to leave.

As usual, we are assuming a right-hand propped boat and no bow thruster:

- If you have a left-hand prop, just reverse everything.

- If you have a bow thruster, a lot of this will be easier, but don’t make the mistake of relying on it too much, since most yacht thrusters are pretty wimpy, particularly when put up against the power of current or a strong wind, and they can also fail unexpectedly, often, I gather (never had one), when the thing overheats and the thermal cut-out trips—could ruin your whole day.

Anyway, when faced with a difficult situation like this it’s easy to flat line because it all seems so complicated and just blunder in hoping for the best, but that’s an almost sure path to disaster.

We lost count of the number of times we saw boaters do just that in Charleston—we could tell because of all the confusion and shouting when it all went wrong.

We AACers know better…but only if we have carefully read the preceding chapters in this Online Book.

Before we even start the manoeuvre we need to break the situation down (as we learned in Part 1) into manageable pieces and figure out:

- Our turn using prop walk and prop wash, taking into account turn sidle.

- How far and in what direction to move the starting point of the turn to account for the current.

- How the turn will be helped or hindered by the wind.

Once we break it down like this, things get way simpler, and we can immediately see that there are only three ways to screw it up:

- Attempt the turn against the direction of the boat’s prop wash.

- Misjudge the current strength and then compound the error by starting the manoeuvre from a position that leaves us no way to abort and try again—competent mariners always have a bail-out option.

- Forget to properly allow for the effect of the wind and so get into a situation where we can’t complete the turn and will have to back out, which might be impossible depending on current, wind direction and the strength of both.

The first is easy to avoid as we have already learned:

- Right-hand prop: turn must be clockwise.

- Left-hand prop: turn must be counterclockwise.

We are going to leave wind out of it for a minute while we look at four current scenarios:

Hello John, excellent article as always and I’m looking forward to re-reading the series.

A minor typo in the “Trapped!” section:

I believe this should be “prop walk.”

Hi Chuck,

Great catch, thanks, I will fix it. And thanks for the kind words.

Living in Maine I’ve come to consider a folding prop a necessity due to all the noodles in our soup. The reduction in reverse power hasn’t concerned me much since I’ve not entered a tricky marina in a very long time, and won’t until I’m traveling abroad. Meanwhile I opted against a thruster for the new boat. Luckily the beaching capacity allows for prop changes. Maybe if I’m going to be visiting marinas a bunch I’ll install a fixed or feathering prop.

We have a steel sailboat with considerable windage, a full keel, and no bow thruster. We have to be particularly careful in scenarios such as this, because a) the boat is not immediately responsive to throttle; b) resists tight turns; and c) will definitely incur damage if it hits another boat.

We do have a feathering prop, however, which is differentially pitched in forward (flatter) and reverse (coarser) for more thrust in reverse. We’ve practised “rotation in place” away from other obstacles as propwalking in reverse to port and then putting the helm over to starboard for a small shot of forward (repeat as necessary!) is the most controlled way to get the bow around.

I encourage people to practise these maneuvers next to a harmless buoy marker in a sufficiently deep river mouth or in obvious current. You can learn a lot about what your boat can do…and what’s going to be problematic…thereb, which in turn will suggest whether you should attempt tricky landings in the first place. Interestingly, in my first boat, an IOR-influenced C&C, I could back out of a slip and continue in reverse right out of a lane using the tiller, but that was a much lighter, lower boat.

Hi Michael,

There’s certainly nothing wrong with a folding prop and I’m perfectly happy with the one on our new J/109, but then she is light and pretty easy to stop. And as you say, much less fouling risk.

I would never trust one on a boat like our McCurdy and Rhodes tipping the scales at 25 tons. On that boat we had great service from a MaxProp and would highly recommend one if you do decide to change. As to fixed props, I would never have one on a sailboat, no matter what, just too big a performance hit, but that’s me.

I’m personally very down on feathering, since the day I got hooked by one of those submerged pots, which got me hooked on a second one at the same time 100 yards to windward of an island. So if I stick with folding, perhaps the answer is a good anchor, a good dinghy, and patience.

I have a full keel, as I said, and sport a rather vicious-looking line cutter on the shaft, both of which mitigate, but do not entirely avoid, the problem. But I do sympathize.

Hi John,

I find nothing to add to these explanations. Logic and true. You present hands on “users manuals” to specific situations, which can be used to get general understanding of the influences we’re exposed to and the tools to handle them, so we can analyse and solve most any situation. Practice makes it far easier and more intuitive than one might think, while wrestling the theory, imagining how a small error can kill our self esteem, and possibly our wallet. 🙂

I teach new tourist boat skippers how to manoeuvre their boats in the Amsterdam canals. This task might look impressive, but is actually mostly easier than the problems described in these articles. The space is extremely restricted all the time, but wind and current are mostly limited. The difficulty is just getting used to minimal tolerances. Still, the overwhelmed feeling is the same. Maybe because they have perhaps a hundred passengers watching them.

I’ve found that the easiest way to make new skippers grasp the important points is:

– Only focus on the essential main rules. The finesse comes later.

– Make tasks into sequential steps.

You do this in these articles, but with all the info necessary to understand why, not only what. I love that, but many struggle when having to do both simultaneously. When we have observed that the “what” worked, we can understand the “why”. If I try to serve both before the try, we mix the two into confusion. I’m no exception, if I analyse and plan too much.

To avoid that I make a mental image of:

1. When/where can I establish “safe stages”, where I can pause during the manoeuvre. The boat orientation is so that whatever the wind and current does, I can easily avoid hitting anything, and keep stable like that for some period of time. I can use a “safe stage” to choose the moment I want to move on or retreat.

2. Where can I define “action points”. That’s the located points where I need to start some action. The precise location will be updated continuously as I see more, but I will want some sort of definition made up front. Something I can look for and use as a tool to know that now is the time, or a new situation will arise.

What those safe stages and action points are depends on the boat, conditions and crew, of course. A situation becomes safe when we have tools to control its important factors. When in in tight quarters, the main point is to not hit anything. Counterintuitively, having the boat oriented across the narrowest distance is when we have the best control over that. It might not feel “safe”, but is really a time to relax and evaluate the situation, unless, of course we’re running out of space some other direction. Since this orientation is often in the middle of the manoeuvre, it’s often a revelation for fresh skippers that it’s actually under control, no stress.

In one of the situations described in the article the current is pushing the boat parallel to the rows of boats close on either side, inwards to a dead end. One strategy for solving that with the above thinking could be:

Turn the boat sideways plenty early. Drift sideways with the current towards the wanted spot, correcting the position with small thrusts fwd and reverse. When closer, gradually rotate the bow against the current. Calmly enter the spot.

When the current goes across the narrow space, moving towards the spot has to be at some speed, which makes it not really feel like a “safe stage”, but at that speed we are still in a very predictable and controllable situation. We might visualise various scary outcomes, but as long as we are aware of the actual control and stability of the current situation, we might be able to relax and focus on how to define the “action point” leading to the next “safe stage”, which might be the bow against the current, again across the narrowest available space.

This already got far too long, as usual, and there’s no way I can be as complete as these articles, but I hope I managed to make my system of thinking clear enough, and that it might be useful for some when they try to solve the riddle of a complicated situation.

Hi Stein.

Great comment, I love the safe place, action point concept. I had never thought of it that way until I read in your comment, but as soon as I did I realized that’s what I have always done intuitively.

And I totally agree that the safe place is when we are across the channel. This is when I relax too because I know I have many options. I tried to make that point, and particularly the danger of not getting half way trough the turn fast enough in the “Trapped” section, but you have added a lot to that.

I also like your idea of how to handle being swept in.

Thanks again.

John,

Your J-109 has the dreaded Saildrive. Have you experimented enough with it to determine the effect of propwash/propwalk compared to more traditional shaft driven props? Are your instructions the same whether you have a saildrive or a traditional prop or do those of us who have a saildrive need to modify things?

Hi Eric,

Yes, first thing I did when we put her in the water for power trials was experiment with prop walk and wash and I can confirm that she has plenty of walk. In fact far more than I expected, which puts paid to the theory that prop walk is caused, or at least increased, by the downward angle of the shaft. She also pulls quite hard to port on the helm when motoring hard which confirms that. Not a problem you understand, in fact I was quite relieved to find she had plenty of walk, particularly since she has a folding prop.

As to wash, not as much as my old boat, but then again, the rudder on the J/109 is hugely efficient and spins the boat on a dime to the point you could easily throw someone off the bow if not careful.

All in all, she will be very easy to manoeuvre under power, and she even backs down in a straight line.

So, bottom line, no change to instructions for a sail drive boat.

It’s really quite remarkable how much easier a boat is to handle when you treat prop walk as a useful tool, instead of as an annoying inconvenience.

There must be nearly as many wrong, half-assed theories about where prop walk comes from than there are propeller designs. This confused the hell out of me when I was younger. As it turns out – and this is very clear when you visualize a full 3D flow field, eg. in a CFD result – prop walk is a very natural, obvious result of the fact that the water flow around a propeller is spinning, and therefore applies different forces on the port and starboard sides where that spinning flow hits pieces of the boat.

Hi Matt,

I agree on all points, but I find it easier to see it as a resultant asymmetric water flow. If the propeller rotated in open water, no structures nearby, the flow around the prop would be symmetric. The rotating water flow is significantly larger than the propeller diameter, especially before the boat has gained speed. The water rotating along with the top of the prop would spin off outwards from the blades to one side, the water rotating along with the bottom of the prop would spin off at the same angle and speed, but in the opposite direction. The forces they create would neutralise each other, so there would be no prop walk.

If we add a hull or something else close to the propeller, usually above, that structure will block some of the rotating water flow from being thrown off to one side, creating an unbalance between the top side and bottom side flows. That means water on the less influenced side will create a sideways water flow that pushes the boat the opposite way.

Did this improve the understanding for anyone? Looking at flow models it seems obvious, but I don’t feel words make it as clear…

Hi Stein, your words help clarify things nicely to me, thanks for that (and same to Matt M)!

Hi John,

I think this is a very good way to think about it. The only minor things that I can think of which are not discussed are:

Eric

Hi Eric,

All good points. I’m going to get into more on that stuff later in the series. I figure if I add all that to each article as we go along the fundamentals will get lost in the details. Getting this balance right between the big picture and the details is, at least for me, the hardest part of writing this kind of thing, particularly since our scroll depth analysis shows that people tune out and stop reading after about 2500 words.

Hi John,

I hope I didn’t front-run any of your future articles, apologies if I did. And thank you for the work you do in understanding what is digestible. To Stein’s point above, this site does a good job of focusing on the essentials and doesn’t get bogged down in details that are too specialized.

Eric

Hi Eric,

No problem, in fact I will punch up the point about how boats, particularly deep draft ones, change the current. I did mention “swirls” in Part 1, but you comment reminded me that I need to expand on that. Thanks

My answer was more for the benefit of others so they would understand what my strategy is on this, and to stick with us through to the end.

We’ve noticed this effect in current also, when our boat refuses to act according to its typical behaviour. We always have one extra-long line to throw to the dock (assuming someone is there) if we miss the fact that Plan A will not resolve as we expected. The role of eddies in providing breathing room (or just figuring out why the result is counter-intuitive) is an interesting one.

John, just saw this video and the next one which follows. Think you may be interested.

alexis

Docking in Bagenkop (Denmark) in heavy wind – YouTube

Hi Alexis and all,

Lots could be said about the first, but it should be noted that all got secure and sorted with no damage to the boat or the crew. When I am around hard things, that is always my first priority: all else, especially looking good (or not looking bad) comes well after.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Alexis,

Well worth watching. Not an easy situation to pull off, and, as Dick says, nothing bad happened. But if here had been a boat in the berth to leeward, there would have been a good bump.

I think if face with that I might have come in bow first and alongside the outer pilings parallel to them and with the wind on the stern, so that the crew could drop a line over what is going to become the windward piling. Once that line was on I could back off a bit, kick the stern to starboard in forward and then let the wind blow the stern off and pivot on the line made fast just forward of amidships until lined up, but with the bow pointing a bit to windward.

At that point all is under control and the crew can toss another line to the bystanders for the windward bow. The boat can then be worked in on both lines and we end up with the first line being the windward stern line on the piling. That can then be eased to drop down and get the leeward piling line on.

Done this way, we can even pull it off without bystanders, but that’s a full article.

Going in forward, if that is easier, and then warping the boat around to face out, may be another option. One can usually warp a boat around in its own length, all under control.

Hi Ron,

Sure, that’s an option. On the other hand, with a bigger boat like our M&R 56 combined with current the loads on lines when turning a boat like that can be very high with all kinds of ways crew members can get hurt. Think about 25 tons with accelerated by a two knot current! So I would want to wait for slack water and little or no wind before trying it.