Susie Goodall was one of the few competitors in the Golden Globe Race 2018 with a series drogue to Don Jordan’s design or, for that matter, with any capsize prevention gear at all.

Given that, it’s horribly unfair that when she was deep in the Southern Ocean and deployed the series drogue to survive a horrendous storm, it failed her. Her boat was pitchpoled and trashed to the point that her only option was to call for rescue. The good news is that the rescue went as well as these things ever do, although I can’t even imagine how harrowing this experience must have been.

Once Susie was safe, the important question became what went wrong and does her terrible experience indicate a fundamental problem with the series drogue and/or Don Jorgan’s science and engineering? Let’s dig in and find out:

What Broke

Susie’s series drogue parted off where it attached to the bridles as her Rustler 36 was running down the face of a huge Southern Ocean storm wave.

The join that failed was made by cow hitching spliced loops on the outboard end of the bridles to a “flemish loop” made by tying a figure 8 knot on the bight (see the photo at the start of this article) on the inboard end of the first section of the drogue.

I got this directly from Angus Coleman who made the drogue and his information is based on a personal call with Susie:

I spoke to Susie a couple of weeks ago.

It appears that the flemish loop that was on the inboard end of the drogue failed…

Climbers tie what is essentially the same knot as a follow-through figure of eight, and regularly trust their lives to it, so the knot itself was not the problem, or at least not by itself.

Rather, I think that we can deduce with a fair amount of reliability that the failure was, as so often happens when stuff goes wrong, particularly at sea, the combination of several factors—three in this case:

#1 Reduction of Strength From The Knot

All knots reduce the strength of the line they are tied in. That said, how much for a given knot is open to debate…lots of debate. Generally, most authorities say a 25% strength reduction for the figure eight. But since we are dealing with a safety of life issue here, let’s assume 30%.

#2 Boat Displacement Higher Than Specification

Now we are entering the realm of speculation, but experience-based speculation. The listed displacement of Susie’s Rustler 36 is 16,805 lb (7,623 kg), but there are a bunch of factors at work that almost certainly mean that the boat was heavier at the time of the accident, probably much heavier:

- The hull would have absorbed a lot of water over its long life and more after being refitted.

- Builders typically quote half load, and some even no load, displacements.

- Boats, even brand new ones, usually come out of the yard heavier than their design numbers.

- Susie’s boat was strengthened and modified for the race, which would have added weight.

- Given that this was a round-the-world non-stop race, I’m sure Susie was carrying substantial weight in spares and provisions.

How much would this all add up to? Obviously we can’t know for sure, but I have a very hard time believing an actual displacement of under 20,000 lb (9071 kg), and I could easily see that number being much higher.

It’s hard to tell, but the boat does look well laden down in this photo and this one, as well as the shot above that Colin took before the first start in Falmouth, which substantiates my analysis above.

# 3 Drogue Choice?

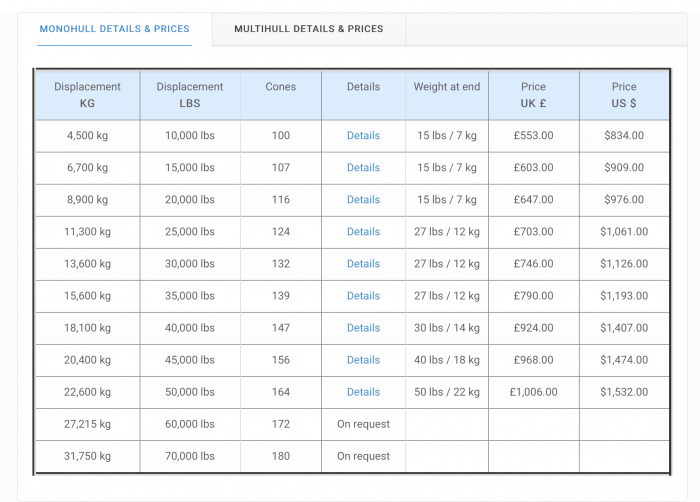

Let’s now have a look at the Ocean Brake series drogue sales page:

As we can see, the most obvious drogue to choose is the 116-cone model specified for boats up to 20,000 lb and Angus confirms that he is near certain that was the one he sold to Susie:

The drogue that Susie bought from me was a 116 cone drogue, and as I have no notes to the contrary, I can only presume it was the 5/8” line…

Now let’s drill down to the spec:

The key part to zero in on is:

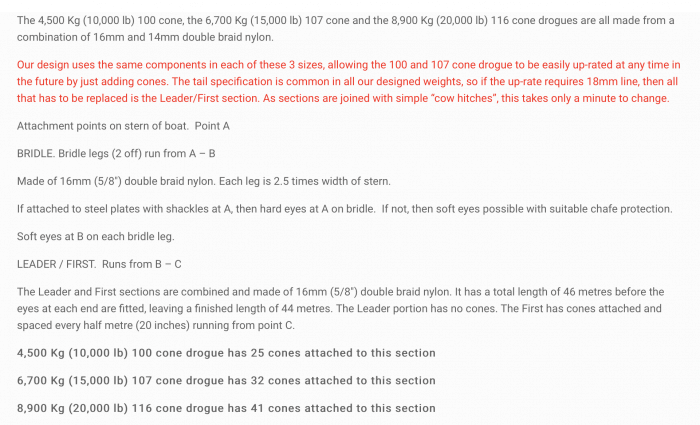

Our design uses the same components in each of these 3 sizes, allowing the 100 and 107 cone drogue to be easily up-rated at any time in the future by just adding cones.

All three sizes of Ocean Brake’s smaller boat drogues use the same 5/8″/16mm line. Susie’s boat would have been at the upper end of the range, even if its true displacement was just 20,000 lb.

Putting It Together

So, we can see what happened:

- The break load on 5/8″ braid nylon is about 15,000 pounds.

- Assuming a 30% reduction for the knot we end up at 10,500 lb.

- But Don Jordan’s design load for a 20,000 pound boat is 13,000, over a ton more.

Jordan defines the design load as:

The design load is the ultimate, once in a lifetime, peak transient load that would be imposed on the drogue in a “worst case” breaking wave strike.

And Susie told Angus:

She also tells me the particular wave was massive, as she was completely in the lee when in the trough mast and wind instruments all.

So there we have it. Susie was:

- unlucky enough to encounter that once in a lifetime wave (probably more common in the Southern Ocean),

- at the same time she had a heavier boat than listed in the specifications,

- which, in turn, loaded a knot that reduced the strength of the rope to a value below the load,

- and so the drogue parted off, resulting in rapid acceleration down the face of the wave and disaster, just as Jordan predicted.

Could I Be Wrong?

I bounced this idea off Angus in an email a couple of weeks ago. Here are the key quotes from his answer:

…My thoughts are very much in line with your calculations…

…Susie sent me a picture of her leader section where the loop had failed. I attach it below. You can see the frayed end just by the first knot…

I think that puts any doubts about what happened to rest. By the way, I wish I could publish Susie’s photo, but I can’t until I have her permission.

Why a Figure Eight?

At this point you are probably wondering why Ocean Brake built Susie’s drogue with the knot. I will let Angus tell you himself:

…We stopped using flemish loops about a year or so ago in most cases, as it was only to allow people to add more cones more easily. We only use soft eye splices on the inboard end of the drogues now…

The law of unintended consequences strikes again.

Learning?

So what can we all learn from this? Here’s what I get:

Don Jordan Is The Man

Given that this is the first time I have ever heard of a series drogue parting off, other than from chafe, and that Susie’s did, probably at just about the load he predicted, Don Jordan is pretty much dead nuts accurate on his once in a lifetime design load.

Displacement

We would all be well advised to add at least 30% to the designer’s displacement number when specifying a Jordan Series Drogue.

Knots and Splices

A series drogue should never be attached with knots. And, of course, if you find you have one of the Ocean Brake drogues with the figure eight, that first section line should be replaced with a spliced one.

By the way, whenever I’m thinking about rope and need answers, I call up my old friend, and rigger of Morgan’s Cloud for a quarter of a century, Jay Maloney.

Jay told me that he, and his colleague Mike, spent some time at Yale Cordage doing double braid splices and then having them destruction tested.

Safety Margin

Once again, given that this is a safety of life issue, and even though this accident only reinforces my faith in Jordan’s science, I for one will be looking at our series drogue to see what the safety margin is. And if it is less than 25%, we will have at least the first section redone in Dyneema to get to that number.

In fact, I would go a step further and say that the more I learn about all this, the more I think that all series drogues to Jordan’s design should have at least the bridles and the first section made from Spectra/Dyneema.

That said, there are drawbacks to this approach too, that need to be dealt with.

Summary

Anger or Not

I want to close with one final and, I think, very important point. Mistakes were made in choosing which Ocean Brake series drogue was right for Susie’s boat and in using the figure eight knot in place of a splice.

That said, I don’t think it would be fair, or sensible, to direct anger at Angus Coleman and his staff at Ocean Brake. The bottom line is that theirs is a business of making safety devices, with razor thin profit margins, to operate in an unpredictable environment.

Sure they made mistakes, but take a look in the mirror and see if the person staring back has not done the same—I fail that test, big time, including getting the bolt sizes wrong on our series drogue chainplates.

And, further, Angus has been absolutely frank about what failed, has already fixed it on future drogues and will fix existing drogues too:

…I would be happy…for anyone with a flemish loop on the inboard end of their leader to send in their leader section and we will splice it instead at no cost…

It would seem that Susie agrees since she told Angus that she remains a firm believer in the series drogue and will be getting another one from him.

Further Reading

We have an Online Book full of storm survival tactics and gear that works, based on real-world experience from the Southern Ocean veterans mentioned above, and others.

The Book includes in-depth chapters on what you need to know to buy, fit, and deploy the series drogue as designed by Don Jordan, as well as other experienced-based chapters on heaving-to.

thank you very much for this report. It is vital we we all understand this event. My drogue by Ace Sailmakers uses 7/16 dyneema for the bridle, with spliced eyes. If and when I go distance cruising again, I may replace some or all of the 3/4 nylon tail with dyneema to save weight and make it easier to launch.

Hi John

Much to like here. Much I agree with…eg

– Susie’s capsize does not constitute evidence that JSDs don’t do the job they are designed for. (Personally I would like to see many more cruising yachts carry and deploy them.)

– How a piece of kit is built is fundamental. If it breaks when you need it, it’s as good as a…

– Using knots and/or marginal rope sizes for something like this doesn’t seem the best option. Don’t skimp.

However, before hammering home the conclusions too hard, perhaps we should wait for more information. We don’t actually know what size rope she was using, and that piece of information is central to your article. Surely Angus from Ocean brake knows that? He hasn’t replied. Susie hasn’t replied either.

Without wanting to be critical. Are we skating on thin ice slightly for a fairly polemic article?

====

Whatever the outcome of the other discussion over on the GGR article comes up with in terms of a solution for “keep JSD bridle clear of windvane” options: Wouldn’t it be great if the learnings from Susie’s failure and that windvane solution just became part of the JSD product from Ocean Brake. So people don’t have to re-invent the wheel – or do the difficult testing – and it will actually work close to 100% of the time if they are in the unfortunate position of having to use it.

Oliver

Hi Oliver,

Perhaps I was not clear enough in the piece:

Given all that, continuing to sit on what I know would, at least to me, have been irresponsible.

Can we be certain I’m right. Of course not, that’s why I brought it up in the form of a headline.

Bottom line, in my experience there is little certainty in general life, and even less offshore. Given that, I try to do the right thing based on logic and analysis. I feel that I was dully diligent and probably right. At this point, each reader can make up their own minds. It was ever so.

Also, given that I went to a lot of trouble not to throw Ocean Brake under the bus, and specifically raised the issue that could make me wrong, I would hardly characterize the article as “polemic”—I did not attack anyone, in fact rather the opposite.

Hi Oliver,

I don’t feel this article is polemic, or that it goes too far out on a limb to find conclusions, or that there are any weak points, or that it blames anyone for irresponsibility. It just describes some facts and tries to understand them to find solutions. I hope there will be even more information about the details, to improve our understanding even better, but I see no reason to not publish this now.

I completely agree that it would be great if the commercially available JSDs came with all the bells and whistles of what has been learned. Probably the makers share that opinion. It would be an extra reason to buy their product, rather than make it ourselves. Thus, I think that will indeed happen. These things do develop to our benefit. The knot was already gone before Suzie Goodall lost her JSD. Oceanbrake and probably Ace Sailmakers follow this site and will no doubt let discussions and ideas inspire their thoughts.

Sobering analysis John,

How careful we have to be to “sweat the small stuff”. As you point out, small errors have a habit of adding up, or perhaps compounding when a system like a JSD is involved.

I was at an event on Friday night listening to local sailor Phil van der Mespel recounting a passage returning up the West Coast of New Zealand (the wilder side) in around 45 knots of wind and more significantly, some large waves. Having a smallish (9.5 m) older wooden boat, he made the decision to stow the sails and deploy his JSD. Having done so he locked in his hatch boards and went down below to the galley.

After a meal, he noticed how much the conditions had eased off and was thinking this was typical “you deploy the JSD, and then the wind drops away”. Returning to the cockpit to re-hoist his sails he recalled being “hardly able to stand up”. A glance at the wind instruments showed the wind blowing 60 -> 70 knots. He couldn’t believe how wild it was outside and yet how docile everything felt down below, even in his small craft. He was able to safely ride out the storm and in the later Q&A, said that retrieval was easy.

Sadly, he went on to recount how he failed to stop and deploy the JSD on a return delivery across the Tasman from the Pacific Islands in 2017 and fell out of successive waves when solo sailing his boat, upwind at the time. He had to abandon her when the mast came down and holed the boat and he talked about his abandon ship process and subsequent rescue.

I thought the first part was a useful first person account of a yacht about the same size as Susie’s and seeming to support that the JSD failure wasn’t related to the scale of yacht, but the relative set-up.

Kind regards, Rob

Just a point of logic and deduction: we do not have evidence, from this case alone, to indicate that Don Jordan’s once in a lifetime load calculation is ‘dead nuts accurate’, although it may be. We only know the load was greater than the strength of the flemish loop. It could have been much greater. I’m not saying that’s likely (I simply don’t know), just that the load being ‘greater’ is all we have definite evidence for.

Hi Geoff,

I disagree. To my way of thinking, we have two bracketing data points:

Therefore I think it is logical to assume that Jordan’s numbers are correct since they have worked for over two decades and Susie’s drogue parted off when subjected to loads above it’s strength, loads that Jordan also predicted, with exactly the results that Jorden predicted.

QUOTE “but we can also be fairly sure that it was about 30% below Jordan’s strength requirement”

Certainly you have demonstrated that her set-up was weaker than the calculated once-in-a-lifetime load. And the event itself obviously proves that it was weaker than the maximum possible load. But the event only measured a binary threshold: above (breaks) or below (doesn’t break) the strength of the system on the day. And we know it was ‘above’. There is no way, from this incident, to show that the max load was below any calculation. If you are satisfied, from other experience, that Jordan’s calculated max load is correct, then fine. But this incident does not give you additional evidence on maximum loads seen in the field.

Hi Geoff,

I agree, but what it does show is that a series drogue 30% under Jordan’s load calculations will fail. To me that’s an important data point and that’s what I wrote—I specifically said that the upper limit was supported be other usage, not this event. See below:

Thank you John for digging into this and making the choice to publish your analysis. When I purchased my series drogue for Oh! I felt I had been over sold on the size . After reading your analysis, I am now glad it is the next specification size up for the design weight of my catamaran. The next step will be examining the bridle attachments to verify they are splices. Thank you for all the great articles and research at AAC. Cheers, Rod Morris

Hi Rob,

Glad it was useful, and thanks for the kind words.

As Terence described, I also have a drogue built by Ace Sailmakers that has a bridle made from dynemma with spliced loops. Also of note is the fact that the loop and the entire first section of the bridle comes fitted with chafe gear which not only protects where the loop contacts the connection points on the hull but also where it might accidentally rub parts of the hull and/or vane gear. I couldn’t imagine making this connection without some chafe gear already in place – as I think it would be impossible to add after deployment.

On another note – as I recall, Trevor Robertson described having to adjust the length of the bridle to change the orientation of the stern relative to prevailing wave trains. I believe he mentioned tying off the bridle on welded stern posts to do this? Not sure how this would work with the fixed eye splice idea or how you would add chafing gear in this situation?

Hi Glen,

Good to hear about that chafe gear. If you have a moment, I would be very interested in seeing a photo of exactly what David is doing with chafe gear.

As to Trevor, yes he steered the boat on one occasion by shortening one bridle, but this was, as I read it, a choice to make things more comfortable, not a requirement for safety.

That said, those with chain plates that wish to do the same, can attach a third line at the point where the bridles meet and then lead that to a winch to accomplish the same thing. One caution: I would make sure that said line was weaker than the winch.

The other benefit of doing this, is that the third line can be used during retrieval: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/jordan-series-drogue-retrieval/

Hi John – I emailed you some photos of the drogue. Sorry, didn’t have an easy way of posting them. Looking at the photos I forgot that the eye splices had welded thimbles and the chafing gear extends quite a ways down the bridle. With additional chafe gear at the point of transition to the cone line – considering that the two sides of the bridle may rub together. I did pay extra for the chafing gear. Haven’t had to deploy it yet, but worth every penny in my opinion.

Thanks for your comments about Trevor’s setup. I understand now how one could manipulate the angle with with a winched line from one side of the bridle connected with a rolling hitch. If that line failed the bridle is still attached. : )

Hi Glunn,

Thanks for the photos, very useful.

Hi John,

There might be one more relevant factor in this: Rope strength diminishing with age. Partly from use and partly from exposure, especially to sunlight. Suzie had her JSD for some time before the GGR. I believe to have read somewhere that she had it two or three years, (not reliable info.) Since her version had the knot that Oceanbrake has already stopped using, it must have been an older model.

Either way, since she’s been sailing alone a lot and mostly on ocean passages, it’s fair to guess that she has had the JSD rigged most of the time. The JSD itself will be well protected in a bag, unless it’s in use, but parts of the bridle will not be. The part that broke should however normally be in the bag, but I don’t know. Also some bag cloth let quite a bit of ultraviolet light through, the destructive part that apart from giving us cancer, also breaks down plastics and more. If the knot was on top of the JSD pile, which is probable, only the cloth would be between it and the blazing sun. It might have gotten enough UV light to be seriously weakened.

Her JSD had been deployed on several earlier occasions, meaning that the knot in discussion was properly tight. It would probably feel hard as a rock. When the rope fibres are that tight over time, the molecular structure can change. The material creeps. Also the very tight material is laid more bare to the elements and more vulnerable to chafe. Nylon is so stretchy that load distribution on all the fibres in the knot will probably be good, as opposed to some stiffer rope materials, but otherwise, Nylon isn’t the best material for staying highly loaded for a long time, as in a very tight knot.

It does indeed seem overwhelmingly probable that this knot and the JSD and rope size chosen for the heavy boat, and then ageing on top of that, were the reasons for the failure.

I completely agree that one should use HMPE (High Modulus PolyEthylene), like Dyneema, or similar in the bridle and anywhere else it’s practical. To remember the name, just think of the traditional rope material Hemp, but move the E to the end, HMPE. 🙂 The more modern fibres are also not completely resistant to ageing, but still better than Nylon, and the modern fibre ropes are vastly more resistant to chafe. Their robustness approaches that of steel wire and are for that reason used on trawlers. (Off topic, but trawlers should be forbidden globally. Destructive fishing method!) The much lower weight and bulk of the modern ropes also makes it much easier to pick a rope with a huge safety margin.

A long life of racing extreme boats, having to make everything very light, robust and simple, has made me fall in love with the high tech fibres. They must be used right, but then they are just awesome! (Nope. I’m not selling it.) 😀

I too, wondered about that. I’ve also seen data that suggests knots are weakened, proportionally, slightly more when wet. When we add fatigue to the mix, I wonder if the actual strength was down to 50% or less. That said, Jordan would have made some allowance for this is his calculations.

The reason climbers use a figure 8 is not ease of use, it is because when you pull the rope up the cliff, a splice will catch. And although climbing ropes are severely tested in a fall, it is NOT the knot that fails, it is where the rope passes over a sharp edge or worn carabiner.

Some lines are sized for wear and stretch; sheets, halyard, and most trimming lines. Some systems operate more closely to the limits, particularly in extreme cases; standing rigging, jacklines and tethers, sea anchors, and JSDs (not other drogues, not so much). In the latter catagory, yes, details matter.

Hi Drew,

I would have to read through his stuff again to be sure, but I’m pretty sure that Jordan assumed splices not knots. And anyway, he certainly expected people to build to his design loads taking into account all factors including knot strength reduction.

As you say, details matter. More coming.

Hi John,

as far as I see it Don doesn’t mention splices or knots either, he bypasses the actual attachment technique but states:

-) “The bridle […] divides the total load […] into strong points at the corners of the transom. The attachments […] should be designed to take 70% of the design load.” (p.56, bottom)

-) “All elements […] must be carefully selected. […] All shackles, eyes and swivels must be rated above the design load.” (p.59, top)

IMHO this shows a brilliant engineer here – he states the goal that must be achieved very clearly. How to get there is not so important as long as all elements are strong as needed, or even stronger.

(Citations from http://www.jordanseriesdrogue.com/pdf/droguecoastguardreport.pdf)

Very thought provoking article and subsequent comments / discussions.

I noticed from the photograph of your boat and the connection to your chain plates that you have the life raft on the aft deck – is this a good position/given that to deploy it in a heavy sea you would need massive strength to deploy and luck not to damage it in doing so . Perhaps positioning of life rafts could be the subject of an article in the future.

Hi James,

Yes, I think it’s a very good position. In fact we moved it there some years ago from the cabin top forward of the cockpit since we felt it would be both less vulnerable and easier to launch than from it’s old position. (We have quick release hooks on on the lower lifeline, so it’s relatively easy to slide it off the cradle and over the side.)

That said, we have a centre cockpit boat and plenty of room back there, so I’m certainly not saying that this is right for all boats.

If you put liferaft in the search box (top right) you will find a lot of other stuff I have written on the subject, although not for some years.

Hi All,

I just heard from Angus at Ocean Brake. See the update in the post above for what he has to say.

Stein Varjord hypothesis make a lot of sense. So glad i purchased the dyneema version of the Jordan drogue from Angus ! But i will make sure everything is protected from UV if the bag is stowed outside.

Despite the fact that some other vendors are using this incident as a rationale not to buy JSD type drogues, the relevant bit is that that drogue was doing an excellent job of holding back 20,000 lbs of boat right up until the moment that the line failed (in fact the line wouldn’t have failed if the JSD wasn’t doing such a great job). Beefing up the line ahead of all of the drogue cones seems like a no brainer (the line could be very small at the end of the drogue line as obviously it goes up in accordance to how many drogue cones are attached). Looking at the price difference between the smallest and largest sets (about $700), seems almost irrelevant when people will spend $700 on cockpit cushions without batting an eye. Every time that you post a JSD article, I feel compelled to post a link to this on the off chance one of your readers hasn’t seen it yet… if it can’t convince you to buy (and maintain) a JSD, I don’t know what would. I still get chills when I read it. http://www.oceannavigator.com/March-April-2011/Prepare-for-survival-conditions/

This article and resulting comments are superb. Everyone is clearly passionate about it, and yet civil and careful. It makes for a tremendous source of knowledge and experience. There are so few high quality places (online) where discussions like this can happen. I am very thankful for John, AAC, and all of you who comment and share your experience here. I appreciate you helping me learn and think differently about things, including drogue setup and load calculations…

Yes, indeed. I think this article is a very good example of what this site is good at. I was also curious to see how John would handle this given that the supplier is a sponsor – but I am satisfied the piece is genuinely objective.

Solid information and a clear, actionable conclusion: use splices and go a size bigger!

Hi John,

Interesting. It certainly seems like a plausible explanation and this type of failure is at least fixable without a complete rethink of the concept.

Along the lines of Stein’s comment, I think we need to watch what people use for safety factors when putting their own stuff together. The definition of a safety factor is simply the yield stress divided by the working stress. You often hear of people using number like 3-5 or 10 in critical applications. What this doesn’t tell you is what they are using for knock down factors if any on the yield stress. Depending on the industry, this is applied in different ways. For example, the medical device industry wraps it all into safety factors and uses higher ones where required while industrial machinery generally uses lower yield stress numbers number to reflect material degradation while keeping the safety factor constant. For a typical metal component in a piece of rotating industrial machinery, you might see them start with the fatigue limit instead of the yield strength and then knock off 20% for casting and another 20% for corrosion which will give you an allowable stress around 30% of the yield stress. Then, they might only use a safety factor of 1.5 to that number in their design. You would end up with exactly the same part if you simply used a safety factor of 5 to the yield strength of the material and didn’t use a knocked down yield strength but you end up having to do that calculation to end up at this number. The safety factor calculation is really doing 2 things, it is providing some fudge factor if your calculations are a bit off and it is accounting for known issues like fatigue. What you almost never see is a safety factor of 1 using the rated yield strength of the material, even if the loading is perfect, you will almost always have some form of degradation in non static applications which will eventually cause failure. The first major assembly that I designed which failed was due to not getting the adjusted yield strength right, the parts experienced fretting corrosion and I had only accounted for fatigue.

In the case of the JSD, knock down factors that need to be considered are things like UV, water immersion, fatigue, chafe, etc. If I remember right from the ABYC tables, they ended up covering it all as a safety factor and recommended a value of 8 for nylon line. My guess is that a large portion of this is related to fatigue and water immersion. The trick with calculating fatigue is that if you take the total cycles and assume each one is the worst case stress, you end up with a ridiculously conservative design so you need to look at the distribution. When you look at these knock-down factors for nylon line, it becomes pretty alarming how large a line you need for an application. This makes dyneema/spectra doubly appealing in this application as it doesn’t have nearly the issues with wet strength and fatigue so if you are doing it entirely by safety factor, you could run a lower safety factor and the line is inherently much stronger for the diameter. It has been a while since I have read Jordan’s report but the way I hear many people talking seems to suggest that they don’t have any knock-downs on yield strength and they use a safety factor of 1 to the real worst case load, I hope this isn’t right as it is a pretty risky practice. At the same time, if the once in a lifetime load is in fact well known if you use appropriate knock downs on the line you should be able to run a pretty low safety factor. I have not studied line strength enough to suggest exact numbers but this should be considered as well as the exact intention of Jordan’s statement as to whether that was the “real” load or the “design” load (design load includes a safety factor already).

Eric

Hi Eric,

Great analysis as always. I have been wondering the same thing, albeit without the ability to analyze it the way you do.

I think I’m right in saying that all Jordan’s math is in the Coast Guard report, but as I remember, (I will take another look) it’s rather beyond my abilities to understand what safety factors he was using.

That said, I know that Jordan always uses the words “design load” so I imagine he has a safety factor in there. Also, since he designed planes for living I can’t imagine him not being careful with safety factors.

And further, as far as I know, there has never been another JSD that failed just due to load, so that would seem to say his numbers were right.

On the other hand now we do have one that has, albeit at a load about 25-30% lower than design, assuming that there had been no degradation. To me that last qualification is the thing I’m most focused on going forward, and, like you, Dyneema is becoming more and more attractive to me.

More to come in another post once I have had a chance to pull everything derived from this one together.

Hi Eric

I agree with “knock-down” and “safety factor” comments. Also, the modelling errors in Jordan’s work due the techniques involved will likely be significant.

They drove a motorboat past a model yacht in flat water to estimate suitable drogue sizes and estimate the droque forces during a breaking wave strike. They then did a simple deceleration energy calculation (that’s the 40 lines computer program written in BASIC in the appendix). The single most important input, related to the wave, was wave crest velocity, which they estimated based on reports from the 1979 Fastnet disaster in the Irish Sea. They found wave crest velocity to be roughly linearly related to max drogue force.

Modern simulation tanks and/or wave modelling techniques would clearly be able to cut down the margins, but at great financial cost. So modelling errors, compared to Susie’s situation in the Southern Ocean will likely be greater than 2x, and I am cringing slightly and trying to be optimistic here. — BTW none of the model seems to take the superstructure into account at all. The drag force through the wave crest was modelled by towing in flat water. So if the wall of water hitting the back of the boat above the waterline has any significant impact (!?), then it’s not in the model.

It’s not entirely clear to me what safety factor, if any, has been applied to these models. John’s 13,000lbs design load for a 20,000lbs boat seems to be less than the 75% of displacement that seems to come out of the model? — needs looking into further…

At this stage, I would say that in addition to reduced material strength (UV damage/ age) and the knot issue, for which John estimated 30%, the model inaccuracies – given where they came from – should probably not be ignored.

Oliver

Hi Oliver,

I agree that revisiting Jordan’s numbers with new tech would be really useful. That said, I’m not holding my breath since funding is, I think, going to be a problem. (The Wolfson study was funded after the 79 Fastnet when having a bunch of dead people floating around and horrible footage of people dying in real time made it easy to raise money.) And Jordan did most of his work out of his own pocket.

So, before we overthink this too much, let’s not forget that, as far as I know, no other JSD has ever parted off under load without chafe. And that’s a sample set of hundreds (maybe 1000s) over a quarter of a century including some very long passages in the Southern Ocean.

And further, it’s quite possible that Susies drogue was in some way compromised (It was over two years old).

So, yes, science is good, but real world testing is good too.

Hi John

Has anyone catalogued the real world deployments, conditions involved etc? That might be useful input data.

I have only spent a couple of hours reading Jordan docs. To be honest, it’s not very complicated. It would not be that hard to give them a couple of weeks, re-run the models and include more modern Southern Ocean wave data, and then gain an impression of the inaccuracies involved and apply a suitable safety factor to the max load.

As Eric said, that’s what we Engineers do because we appreciate that our inputs and models are inaccurate, plus I would argue this falls into the “safety critical systems” territory, where a generous safety factor should be applied even once inaccuracies are taken into account. Whereas I can’t find any safety factor being applied at all right now (I will happily stand corrected, if I do find it, or someone else can point it out).

Modern rope materials (eg dyneema/spectra, AKA HMPE), give us a much wider range of realistic options without ending up with a cockpit full of 2 tons of rope. So just applying a safety factor for JSDs built in future, might be quite a realistic option.

BTW another interesting thing I picked out in Jordan’s docs was that the “common wisdom” of “it’s fine to use low stretch dyneema” is correct in one sense, it might change the model parameters significantly in the other direction for other reasons.

Jordan says [paraphrasing] “high stretch rope can be problematic, because by the time the stretchy drogue slows the boat, it might already have capsized”. So dyneema is as good or better right? Well yes, but the deceleration energy calculation is critically dependent on the time taken to decelerate the boat – just a simple impulse calc. That time will be shorter with stiff rope. Hence the force will be higher – principle of energy conservation says so. Think of dropping stone on a spring, vs dropping one suspended by dyneema.

The way that impulse interacts with the time of the boat sliding on the wave, would need to be re-modelled, by re-coding and re-running their 1980s BASIC programme to get an impression of whether the dyneema needs to be uprated for this reason as well. (Note I am not capitalising BASIC for emphasis, it’s an accronym for “Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code”).

BTW: How long is such a drogue supposed to last? As a simple purchaser, I would not be expecting to replace it every 2 years, for a system which I (hopefully) never use? Even sails we use every day last longer than that.

Oliver

Hi Oliver,

Once again, I think we are overthinking this. There is no way to reliably track drogue use data in the sailing world, so we need to be practical. (A database has been tried, but since it depends on self reporting it is intrinsically unreliable.) On a practical basis I have been writing about the JSD for ten years and so it seems likely that if douges had parted off, people would have written to me telling me I was barking up the wrong tree—certain no, likely yes.

Anyway, as far as Dyneema is concerned I will be writing more about that in the future. And I have just heard from Susie with some very interesting information that I will be sharing in due course.

And no, you don’t need to replace a drogue every two years. The key with this, like sails, is that if you leave it out in the sun for two years that may be a problem. Not saying that Susie did that, just that it’s an issue.

Anyway, let’s move on shall we.

Hi John and Oliver,

Thank you for the information on Jordan’s numbers, I need to re-read the report some time. I agree that with a lot of additional work, it would be possible to get a much better handle on the numbers. There are a few methods of making sure that the combination of predicted loads and safety factors are adequate: 1) do rough modeling and apply a large safety factor, this is easiest but not well optimized 2) do detailed modeling and correlation testing as needed which is optimized but time consuming 3) do rough modeling and lots of testing which is not optimized. I generally dislike option 3 as testing is really time consuming, not good for optimization and in this case could be dangerous but in many ways, we have already done option 3 so going back and redoing option 2 would be an optimization exercise which is potentially not warranted as a good track record has been established.

That being said, if we take John’s numbers and say that the drogue that failed was 25-30% under-spec, the best case safety factor is really pretty small on one that is to spec. Because part of the purpose of the safety factor is to account for all of the hard to predict things that happen, maybe the wave was unbelievable and hit the boat just wrong so that the load experienced was way out at the very tail end of the distribution. The problem is that we will never know which feeds back into how hard it is to test your way to optimization. In many ways, I hope that there was some other degradation present so that the factor was higher.

Eric

Hi Eric,

Great explanation of the analysis and testing options. Having now heard from Susie in detail, it does seem that the wave that got her might have indeed been exceptional. That said it’s hard to believe that Susanne Huber-Curfrey, Trevor Robertson, and Tony Gooch with over 5 southern ocean circumnavigation between them and over 30 (minimum, I have not counted) JSD deployments did not have some big waves too. Given that, and that we have no other reports of JSDs parting off without chafe due to construction mistakes (usually the use of wire thimbles on rope) in over two decades of use, I think the actual safety margins must be good. Particularly since many JSD’s are both home made and aging, and still they don’t break.

Sorry, I know I’m repeating myself here, but it’s vital that in all of this interesting discussion we don’t leave those that scan the comments (as most do) with the mistaken impression that the JSD is anything other than by far most affective anti-capsize gear available.

Just ran across this the other day, from page 56 of DJ’s report:

“The design load is the maximum load that will be imposed on the drogue, towline, and attachments in the event of a very severe breaking wave strike. A load of this magnitude would be encountered rarely if at all, possibly once or twice in the lifetime of the equipment.”

Also on page 86 (referring to a nylon towline):

“Since this is a once or twice in a lifetime load, the diameters are based on 60 to 75% of the minimum breaking strength of double braid nylon line. The working load under storm conditions will be on the order of 10% of the minimum breaking strength and well within the fatigue limit.”

This to me suggests

– Jordan expected the system to possibly experience the design load

– Jordan appears to have given consideration to safety factors, at least in the towline diameter, if not everywhere in the report

– As Eric says, it’s necessary to consider “knock downs” on the pieces we spec ourselves, such as bridles, since that will affect how it behaves when experiencing design load

I strived to spec my setup so that deformation but not failure was acceptable at design load. But to be honest I don’t know what are appropriate “knock downs” for all situations. I may opt to attempt to mitigate some of this by, for example, replacing the bridle on a regular interval (they’ll get UV when sitting idle).

Hi Chuck,

I think that’s a very good analysis.

Any thoughts on Dyneema being a floating line?

Looking at the specific gravities of Nylon vs HPME may suggest adding a few Kg to the end weight, or would the massive forces involved when used in anger make this irrelevant?

Meredith Webster

Hi Meredith,

I’m no engineer, so this is just my opinions, but for whatever it’s worth:

I actually think it might actually be smart to do as you suggest, compensate the floatation with som extra kilos on the end weight. That opinion comes from looking at the drawing in Don Jordans papers showing how the drogue is supposed to “hang” in the water with sort of an inverted catenary curve, where most of the drogue is quite deeply immersed, except when there is an especially high load.

This means that the end weight needs to be able to pull the drogue down with some authority. It’s clearly possible to exaggerate the weight, but it seems as if most are far closer the limit of too light. Looking at the videos linked in the comments to the GGR article, I get the impression that the JSD there isn’t held down enough, so it exerts way too little resistance, giving the boat speed of 5-6 knots reported.

I imagine that if the JSD doesn’t get pulled down efficiently, fewer cones will be reliably immersed, resistance will be lower and less stable, meaning the boat will perhaps get a less stable position and a more jerky experience, higher dynamic loads. If my thoughts are correct, it seems one should err on the high side with the end weight, and certainly compensate for floating rope.

Since I’m a weight saving fanatic, (coming from racing multihulls), I’ve always been considering using the stern anchor/kedge chain for the end weight. Since I use a mixed rode with rope, that is easily doable. I haven’t calculated the weight yet, since I also do not yet have a JSD, but think it will be on the high end. A full chain rode would need to be split with a shackle or so, which is probably a bad idea.

Hi Stein,

As I said to Meredith, I just don’t know. A lot of variables here. For example maybe Dyneema would sink between waves more quickly under the influence of the weight at the end due to its lower resistance from being smaller diameter? Not saying that would happen, just that this stuff in very complex.

That said, I thing that you are absolutely right: when in doubt err on the side of heavier.

I did some testing of JSD sections at higher speeds, for use as a steering drogue. It seemed like an interesting secondary use. I learned that the cones behave very differently when towed faster and near the surface. Ace Sailmakers did not entirely agree, and I posted his comments; I’m sure it depends on the speed intended, the amount of weight, and other factors. http://sail-delmarva.blogspot.com/2018/09/edit-why-jordan-series-drogue-is-not.html

I also don’t like the idea a wearing the JSD out on a trade wind passage, when I might REALLY need it later. But of course, the idea is you would only use a short section this way.

Bottom line: Jordan spec a certain amount of weight for very good reasons. He speced a number of cones for good reason. The drogue must run slow and deep to function properly. Change the speed and depth and it behaves quite differently.

Hi Drew,

I’m with you on that, more coming.

Hi Meredith,

I really don’t know. My gut says it would not make that big a difference. That said perhaps the best bet is to just make the first section and the bridles out of Dyneema and then switch to Nylon where the loads are lower.

A very interesting article and again very relevant information for those of us now planning voyages i.e. weight of voyaging boat, extreme loading conditions, design details matter. I am comfortable with the level of analysis being shown and trust that updates will be made when the other information comes to light. Great comments on wear and UV degradation risks. This article and the members comments is why I value this service.

Thanks for the breakdown. I have a point that I thought would be minor but seems less minor after I ran the numbers.

If your knot reduces the strength of a line by 30%, it is insufficient to increase the line strength by 30%. I thought the difference would be small, but:

knotted_strength = (100% – 30%) x rope_strength = 70% x rope_strength

rope_strength = knotted_strength / 70% = knotted_strength x 1.4286

In other words, if you expect a 30% loss in strength due to knotting, you need to increase your rope strength by almost 43% to compensate.

So if you need a breaking load of 13,000 lbs, then your rope needs to have a strength of 13,000 lbs x 1.43 = 18,590 lbs, which is a bit over your estimate for 3/4″ rope.

Obviously splicing makes this point moot and it’s great that Ocean Brake is offering that option.

Hi Adam,

Yes, good point. But the key point is that knotting is a bad idea.

I have one comment, mostly editorial, to your excellent article.

In the second paragraph you state that the

drogue failed Suzy. I think it may be more accurate to say that Ocean Brake may have failed Suzy. Ocean Brake did not build the drogue bridle legs to Don Jordan’s recommendation. He recommended 12” long soft eye splices turned through

themselves with no shackles as the method to attach the bridle legs to the drogue. The use of the knots was not recommended.

Hi Roger,

Wow, I can’t win. Oliver calls my article too angry and you want me to tear Angus a new one.

Bottom line, you both need to read the whole article holistically. I say clearly that Ocean Brake screwed up:

And I went on to say:

One more thing on Corporate Membership. Without their support over the years there would be no AAC, so debating this is academic.

And this is the second time I have outed Ocean Brake for a mistake, and I have often highlighted SPADE’s mistakes.

I have also written a lot of positive stuff about Ace Sailmakers, who don’t supports us.

So rather than making vague accusations, I think it would be a lot more constructive to highlight any places where I have showed bias—taking one sentence out of context does not do that.

If I had hushed up the mistake, that would be bias.

For others interested in our position on corporate membership: https://www.morganscloud.com/2018/11/20/which-old-salts-should-we-listen-to-10-ways-to-decide-part-1/

One other point, my thinking is now that actually cow hitches are far better and safer than thimbles and shackles. More in a future post.

(Note: for others who maybe confused by my answer: Roger wrote to Phyllis directly decrying corporate membership. We did not engage other than to explain why: As you all know, I’m a big believer in transparency and that these issues should see the light of day.)

I did have some concerns about the corporate sponsorship issue – though it is worth mentioning that for me, you have handled this one in a way that leaves no worries about soft pedaling on sponsors.

If you can ever do without corporate sponsors I suggest this might be a desirable path – otherwise you will be *forever* having to raise this and risk the *appearance* of a problem…. but it is good to see that for now you are handling it very well. For an erudite discussion of this, listen to the first ten minutes of a Sam Harris podcast where he explains why he does not take advertising – it is a strong case.

Hi Richard,

As we have said before, Phyllis and I would love to go without corporate sponsorship, if we could just get the member numbers high enough to cover our expenses and a reasonable profit. However growth of members has stalled again and frankly I’m running out of practical ideas about how to fix that. Also, expenses continue to rise, mainly due to ever more onerous compliance and security requirements. Point being, we don’t need convincing of the desirability of being sponsor free, rather we need more member revenue to make it possible.

Anyway, thanks for the kind words on the piece.

Hi all,

With respect to corporate sponsorship, I would be willing to argue that there are few endeavors of importance where we do not have to rely on the integrity of the leading people: that there are always areas of overlap where aspersions can be cast and doubt suggested. It is only the sustained experience over time of these leaders making good decisions and showing that they are operating for the greater good that this kind of trust grows and not, I would suggest, by exertions to be squeaky clean and “unassailable”.

I do think that a necessary ingredient to this building of trust is transparency and a willingness to discuss the possible issues arising. I believe a lack of trust is what leads many to attempt to legislate (corporate sponsorship NOT allowed) to ensure propriety: and to my observation, these attempts usually fail or, when bumping into someone who is willing to do so, are easily circumvented.

I, for one, have no strong desire to have AAC divest itself of corporate sponsorship (although it is also just fine to do so) as I sometimes observe a nice synchronicity, a mutual enhancement, that can take place between products of quality and those who write about and evaluate them (as is occurring on the AAC site). For example, we certainly can’t rely on the vast majority of marine writing and advertising to guide us to quality boats and well-designed gear.

My random thoughts,

Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick and Marc,

Thanks for support on that one. I agree, hard and fast rules do not fix conflicts, transparency and and ethics do. After all, we could have no overt corporate sponsors but still be taking bribes from vendors with no one the wiser. I have also found that those that claim to be totally above bias are often the ones who “protesteth too much”.

In actual fact, I fear I may be rather harder on our corporate sponsors than others, because I suspect that I tend to subconsciously lean over backward to be unbiased.

There’s a clear relationship in my mind between the modest numbers of corporate sponsors you have (and had in the past) here and the rather select group of subscribers predisposed to their products. I’m about to phone Ocean Brake, for instance, to discuss having a JSD made. Clearly, discussion of the “screw-up” has not put me off purchasing a product I have never actually seen on the Great Lakes (which we are shortly leaving). Same with the SPADE anchor we’ve bought: as far as I know, we have the only one in a yacht club of over 220 boats.

So I worry less about being manipulated by the evil machinations of Big Anchor and Big Drogue and more about getting frank discussion about products that appeal mainly to those who go, or who intend to go, well off soundings…a small market.

That said, the conversations here are of a universal nature and would, in my view, be worthwhile for even the weekend cruiser sailors who so outnumber the “adventure” type.

I haven’t seen Randall Reeves’ experience mentioned yet so I’m adding a couple links that might add to the discussion. Here are the cliff notes:

He was knocked down in a south Indian low off the Crozets, set a JSD that parted where it was spliced to the bridle, ordered a new JSD in Tasmania, and eventually had it and the bridle modified based on his experience.

The failed JSD “used a hefty one-inch polyline, and, as connections between drogue and bridle, marine eyes and gigantic shackles.” There are some photos in the video (second link). On his rework of the JSD “dynema has been employed for both the bridle and the first, roughly, half of the cone length, allowing a much smaller diameter (read, lighter) polyline for the after half of the drogue. The marine eyes and shackles have been replaced by eye splices wrapped in chafe gear.”

He seems to have reached a similar conclusion to John based on his experience.

http://figure8voyage.com/disaster/

http://figure8voyage.com/knockdown-in-the-indian-ocean-the-story-in-video-and-photos/

http://figure8voyage.com/two-drogues-aboard/

Hi Christopher,

Reeves’ experience are a lot of what I’m basing my thinking on. That said, I should watch those videos again, so thanks for the links.

In the last link he is obviously leaning towards a single-element drogue (Shark) because it is so much easier to work with. I get that.

But the math on this is obvious and I’ve done a good bit of testing. At peak load (over a ton at 10 knots) any weight you add is nearly irrelevant and the drogue will run on the surface. If you have any doubts of this, tow a drogue at full throttle with weight. The ratio of tension:weight is over 100. This is NOT the case on the JSD because the drag is spread over the length of the train. If you run the same math, with a JSD it runs pretty deep, which we also see in practice. Put another way, 20 pounds on a JSD is many, many times more effective than on a single element drogue, at lease with regard to getting the drogue deep.

Then a steep wave catches up with the drogue. Remember, that waves are only really dangerous when they are steep and breaking. Steep waves have the effect of making the scope on the drogue really low (think angle) and the drogue pulls up and out out of the face of the wave. All that was holding it in was the weight of the water pushed above it. You can see this on many videos, including those by drogue manufacturers. For a few moments, depending on recoil of the rode and other factors, the drogue has near zero drag, until the wave passes and it sinks again. And what people have experienced is that a single element drogue works great in moderate storms, but when it gets past a certain point, with steep breaking waves, repeated sudden failure is possible and even probable. The JSD avoids this by using multiple elements (they are not on wave faces at the same time and they stabilize each other with back pull); even two elements makes a big difference.

And then there is the question regarding whether a single element can provide enough drag during a breaking wave strike. Jordan went through the math and we have discussed that above. Given single element drogues are typically sized for 4 times less drag, draw your own conclusions. Some believe in running free or just slowing, and I choose to avoid that debate due to lack of personal experience. A good single element drogue can control surfing in rolling waves and provide steering–been there, done that–but I’ve never been struck by a large breaking wave and won’t speak to that.

Hi Drew,

You are right. And I have two friends who have had single element drogues pull out of the water at the critical moment resulting in knock down. One was after three days of hard running in the Indian Ocean. Point being, it does not happen often, but it only needs to happen once.

What many people miss is that Jordon did not invent the series drogue and then justify it, as so often happens. Rather he started by testing single element drogues, identified the issue with them, and then invented the JSD to solve it.

Hi All,

Some interesting discussion here, thank to all.

That said, I don’t want anyone left with the impression that the JSD has problems. In fact it works and by having one properly rigged, capsize becomes a solved problem.

So after all this detail, it might be time to read, or re-read this chapter: https://www.morganscloud.com/2018/10/13/just-get-a-series-drogue-designed-by-don-jordan-dammit/

John,

Are you saying that splicing should only be done by a rigger and not DIY? My confusion is that I have tried to find good resources to learn how to splice and they are really difficult to find. I can’t say I”ve found a good guide to splicing. And when I use the guides I have found and try to splice HPME line it is really difficult and I often fail to complete the splice. That makes me think this is really a difficult task to master. It’s that degree of difficulty that makes me want to learn how to do it right myself. I believe that if I’m having this much trouble, the average rigger must be too, which means they are likely to get the splice wrong. I hear you about those like Jay Maloney, but what do you suggest for those of us who don’t have access to the likes of him? I am currently in Indonesia after getting beat up crossing the Tasman and I would love to get rid of some knots and replace them with splices.

Stan Creighton

Hi Stan,

That’s exactly what I’m saying, get a pro.

And here’s an easy test to see if you have the right pro: Watch him or her splice you lines. They should complete a perfect splice with no lumps and the the loop meeting perfectly in less that 10 minutes with no fuss or redoing.

The point being that splicing modern braid is one of those tasks that is not intrinsically that difficult, but it does require practice, and recent practice. (As a sailmaker 40 years ago I could do pretty good double braid splices quite quickly, but I tried one a couple of years ago and it was a mess and took me an hour.)

The other point is that the difference in strength between a good splice and a poor one can be huge because in a poor one the loads are not evenly shared.

More here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2017/10/29/seven-skills-we-dont-need-to-go-cruising/

Hi John,

Interesting discussion! I am at the point of terminating the leader on my JSD. The line is over spec but I guess the loop will have to be formed by a splice now. After reading all the discussion about Susie’s JSD break, and all the general discussion, I am not convinced that the ratio between weight of the boat and the number of cones would cause the leader to break. The load on the knot or splice, and the boat, is generated by the drag from the cones. If the drogue is too small would the effect not be that it does not slow the boat adequately because it does not generate enough drag? The ultimate, occasional, load would come on in a situation like that described by Susie, but that load comes from towing the drogue. It is not like the yacht is hanging from a fixed point (a crane?) by the drogue line. How does the weight of the vessel fit the equation other than from the sudden acceleration? If the drogue is too small, if it does not generate enough drag relative to the momentum of the boat, the vessel will accelerate faster adding something to the ultimate load, but the load is still limited by the drag of the drogue. Isn’t it?

Could the problem be that for a given number of cones, ie. a certain maximum possible drag, the line specification is low?

Like a lot of the readers I would like to know if Susie’s line broke in the knot, in the loop or somewhere else; that is what caused the disaster. But I don’t think that her drogue having fewer cones than what might now have seemed desirable given the yacht’s weight made the line break, except that the leader on the ‘smaller’ drogue had a lower breaking load.

Erin O’Brien

Hi Erin,

Maybe I was not clear. There is no question that Susie’s drogue broke at the knot (see my post above).

Second, none of what I wrote, or believe, has anything to do with number of cones. Susie’s drogue met Jordan’s requirement in that regard. The key point is that the line was not large enough to satisfy Jordan’s design load once it was knotted.

That said, I think you are quite right that drogue load is a function of drogue drag, not the size of the wave.

The drag on the JSD is related to the number of cones and speed. The larger the wave, the higher the potential speed. This data is in the report, but I believe the below formula is pretty close. Check me.

Drag = 24(number of cones)(knots/10)^2

Hi Drew,

Thanks for that, I will reread now that you have set me on the right track. When I get a moment I might have a go at graphing that.

Quick graph for you 🙂

https://www.desmos.com/calculator/lydagalxko

https://i.imgur.com/de2cMFP.png

Not sure what the drag units are though, Lbs?

Hi Craig,

That’s great, thank you! As you say, I need to find out what the drag units are.

It is the same formula I posted, but I started from my own data, so I’m guessing we’re”tight!”

c is number of cones, speed in is knots, drag is in pounds.

Hmm, pounds? This would mean that a 156-cones drogue, as used for a 40.000 lbs boat, would exert between 500 and 1000 lbs drag “only” (3-5 knots), according to the graph? According to Don Jordan, the design load would be 17.500 lbs (see http://www.jordanseriesdrogue.com/D_5.htm)?

Hi Ernest,

I think that Drew’s numbers and Craig’s graph are probably about right since Jordan goes on to say that “The working load during a severe storm is about 10 % of this value”. Also, I’m pretty sure that Jordan will have put a hefty safety factor into his design load.

Put that together and one thing that jumps out is that the wave that got Susie must have been a monster, even though her JSD was weakened by the knot.

Ok, so assuming a knot reduces the WLL by 30%, to support an overall design load of 17.500 lbs using a fig8 knot one would need to dimension the bridle for 25.000 lbs, would that be a correct way of seeing it?

The reason for my question is: if I’m not a good splicer but am able to tie a knot correctly, and I don’t have a splicing expert at hand, would I be in “safe waters” using such a calculation?

Hi Ernrest,

I guess that would work, but I think it’s better to get Ocean Brake or Ace Sailmakers to make up a spliced bridle.

We don’t know what the speed increases to during that worse case hit. If it increases, momentarily, to 7 knots that increases the force by 4 times to about 1 ton. Then add a fat safety factor.

I got an average of 196 pounds from a 90-cone drogue at 3 knots. So that would be about 500 pounds. You can measure this yourself–I say this not out of sarcasm, but because I like to see people repeat tests, because it improves the overall accuracy or our knowledge base. BTW, if it was much higher, recovery would be really, really, hard.

It is well known that knots reduce line strength significantly. Numbers I have seen are similar to those John quotes.

I asked New England Ropes a few years ago about the loss of strength caused by an eye splice. Answer was ” We use eye splices at the end of or test ropes, so the published breaking loads reflect that”

Thus an eye spice will preserve the published rope strength.

Hi Neil,

True, but as I say in the post, a lot depends on the skill of the person that made the splice, particularly in double braid.

Agreed

i guess we can assume that New England makes good splices

Emphasises that amateurs need to be careful

We often have trouble getting the full bury

Hi Neil,

Yes, that’s exactly the trouble I had the last time I tried. That and getting the throat to match perfectly.

John’s writing has always struck me as doggedly determined that anyone offshore not prepared to use a series drogue is stupid/ill-informed/reckless etc. Such dogmatic views need to be carefully considered, in my view. What of local conditions, the boat’s characteristics, the crew’s capabilities etc. I suspect few, if any, readers here did not know that knots weaken breaking strength relative to splicing. He may be right to be so dogmatic. But I have seen enough of the sea to suspect that dogma is not the missing link. What is the point of concluding that the Jordan series drogue design is sound if in Susie’s case it failed because (according to your hints) she used it improperly? Maybe Susie would have been better served by an alternative method? One that she could use to effect having regard to the conditions, her boat, her method streaming etc? – I’m not going to renew my subscription.

Hi David,

I do not see John’s writing as dogma, just a strong opinion.

Even if I did, the rest of the site and this discussion board is still well worth $20/year

Hi David,

If you are not happy here, I would be the last to encourage you to stay.

That said, you might want to read what I have actually written rather than get upset about things I never said: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/storm-tactics/online-book-heavy-weather/

For example we have several chapters on other alternatives and other situations.

The point being that my views on the JSD are well supported by both science and experience, not dogma.

Of course you are welcome to disagree with my conclusions from said science and experience, but denigrating my views (or anyone else’s) with rude words like “dogma” will result in any further comments with the same tone being deleted.

See our comment guidelines.

Hi David,

you said “I suspect few, if any, readers here did not know that knots weaken breaking strength relative to splicing” – and at least in my case you’re perfectly correct. And exactly this kind of information, being abundantly available on AAC, is worth more than multiples of the subscription cost.

And I gladly accept strong opinions from people who have more experience in going to sea than I will ever be able to accumulate.

Hi Ernest and John,

As a general rule, 50% reduction in strength is an industrial rule, (in Australia anyway)

then you have the wet rope factor to consider when working out correct sizing.

http://www.paci.com.au/downloads_public/PPE/12_Wet_rope_dangers.pdf

Thanks, Damian

Hi Damian,

Thanks for the links. I took a look at the first one and as you say they mention 50% in the intro, however, further down in the tables the figure 8 consistently tests in the 70% range, which agrees with other sources I found during my research and my article above.

Of course that leaves the wet factor unanswered, but the second paper makes clear that this is hard to quantify.

So yes, taken together we might conclude that the two papers suggest that the break load on Susie’s drogue diminished by more than 30%, but it’s not conclusive.

Anyway, all of this uncertainty is why, going forward, we will be strongly recommending Dyneema for the bridles and first section.

Hi David,

I believe what you describe as dogma I might describe as pretty close to established seamanship: for now with the information we have, science, field reports and the like. That may change in the future. It is like the “dogma” of saying that I consider the new generation of anchors (SPADE, Rocnas and the like) as far superior to the old generation (CQRs, Bruces and the like). And if it is “dogma” to say that someone venturing far afield with a CQR is mis-guided, then I accept the description.

I would also support vehemence (what you describe as “ stupid/ill informed/reckless”) in pushing for boats traveling in waters where a JSD might predictably be needed to have one ready-to-go on board. Not so much because it is “stupid” to be without (although they may believe that to be the case if the need arises), but because I do not want regulatory agencies to start mandating our equipment or our cruising waters. Nor do I wish SAR personnel to be putting their lives on the line going out to rescue sailors who are not equipped with the predicably necessary ingredients to manage without assistance. I someone wants to go without EPIRB or comm of any sort, perhaps.

John’s vehemence is right in line with a certain responsibility I believe we have to our recreational sailing community to “police” ourselves to some degree: to be clear about safety and seamanship concerns and to communicate those concerns. Either that or others (a government bureaucracy) may step in to do so,

As to the failure: I see that as less a reflection on the JSD and more part of the reasonable (but unfortunate) learning curve, (or perhaps operator error-we do not know yet), as this effective piece of equipment gets better known.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

2 cents worth,

You are clear that failure occurred a the knot(s), but only the figure 8 was discussed.The cow’s hitch, aka the girth hitch,is well know in the climbing community for reducing rope strength by over 50% when cross loaded.What say you?

Hi Peter,

Interesting, I had never heard that. Do you have a source of testing information to support that? Also, what is defined as a cow hitch seems to vary quite a bit. What do you consider a cow hitch?

Hi Peter,

Another thought on this. I just took another look at the photo I have from Susie showing her parted off drogue. It’s clear from the photo that the bridles and the loop made with the figure 8 on the bight were cow hitched together, and yet it’s the figure 8 that failed. Given that testing has shown that the figure 8 reduces strength by ~25% that says that the the cow hitched joint reduces strength less than 25%.

Interesting indeed.As far as I know the cow and girth hitches are the same.I’m not clear how it was all connected,which knot where.My information comes from some years of association with the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides and years of climbing. I’ve not read the hard data but it’s been around for some time. Cross-loading is to be avoided ,a conventional configuration produces a strength loss of about 25% much like high performance knots. This is difficult to describe without photos.

Perhaps of interest – I recently stumbled on this review in Yachting Monthly – their pull test of 12mm double braid suggested a figure 8 broke at 53%. Dry rope and quite a bit lower and only a single pull but makes you wonder…

https://www.yachtingmonthly.com/sailing-skills/strongest-sailing-knot-30247

Hi Robert,

Great link, thanks. A few things jumped out at me:

Anyway, sure does show that we don’t want any knots in a series drogue.

I am very interested in the Jordan Series Drogue. The only JSD’s I’ve seen have been through my computer screen. This has left me at a disadvantage. I would benefit from seeing photos of some of the details of construction and joining. It would clear up some questions that I have.

I’ve seen a number of pictures on-line of the JSD system but it usually showing a big pile of cones on deck or on a dock. I’d like to see the failure points, line section joints and construction details, including line variations and chafe gear.

When someone says that going with all Dyneema would keep the weight down, are they referring to bare 12 strand Dyneema or a braided polyester line with a Dyneema core like NovaBraid PolySpec? Depending on which is used would make a big difference in UV, chafe resistance, loop sizes and construction details at the cones. Without a braided polyester cover, I could see the cone ribbons pulling right through the slippery Dyneema.

What does chafe protection on the bridle look like? What is used and where?

I think I read in a couple of places that soft shackles were used on the bridles and in joining the line sections. Does this really mean using a separate soft shackle or is the line just fed through the its own eye splice like a luggage tag?

These articles make good points about how much the details matter, and words can be sometimes leave room for interpretation. I’m more of a visual person who appreciates a good sketch or a few pictures.

Thanks

Hi John,

Given that I have great faith in the series drogues made by Ocean Brake and Ace Sailmakers, as they are built today, and that I generally recommend against DIY construction, I’m not going to get into a detailed discussion and photos of that nature, which would be more of use in DIY construction. If you do want to go the DIY construction route I recommend reading the two chapters in our online book by Trevor and then refer to Don Jordan’s original work:

You will also find the answers to a lot of your other questions by reading completely through said online book: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/storm-tactics/online-book-heavy-weather/ A quick scan of the comments will also be useful.

I can answer these:

Unsheathed Dyneema has worked well with no problems with cones pulling through. That said, sheathed has retrieval benefits, albeit not as important now that we have figured how to attach a nipper line. More details on the tradeoffs in the online book.

Neither of the series drogues we recommend use soft shackles and I don’t recommend them in this application.

Hi John, after almost a year away from the boat, the Covid ‘lockdown’ in New Zealand has given me time to complete my Jordan drogue, almost. Reading everything by you and the learned community here I believe I’ve got it right; 18mm nylon line with Ocean Brake cones, single braid dyneema bridles and steel bollards like those on Trevor Robertson’s Iron Bark for anchor points. The ‘but’ part is that upon addressing the issue of the loop at the front end of the drogue- which all agree now must be spliced- I find that the line is TRIPLE braid; a normal fine weave sheath, 8 strand 4 thread core, and another core of 6 strands of 4 threads. Maybe I should have looked, but I’ve never heard of triple braid. So, I hope this isn’t too off topic, but I need to know if this stuff can be spliced reliably, given that knotting is out of the question.

Reading the discussion about the reduction of strength in cow hitches I wonder what you think about just threading the the bridle loops on to the drogue loop (before splicing) so that the bridles pull but there is no pinch, either around the drogue line, or in the hitches in the bridle loops. The bridle loops might move around a bit when unloaded but can’t really go anywhere. I’ll have them permanently attached anyway so not being able to remove them is not a factor.

Erin O’Brien. SV Solquest. NZ

Hi Erin,

I’m sorry, but like you I had no idea that there was even such a thing as triple braid, so I have no idea. The only thing I can suggest is to talk to a good rigger. The other option, and perhaps best, is to contact the manufacturer of the rope and ask them how to splice it.

And I think I would still use a cow hitch since I would worry about the ropes moving around and chafing on each other otherwise. Also, I have never heard of a spliced cow hitch breaking at this point on a JSD, and I’m a great believer in the old adage “if its not broken, don’t fix it.” at least in situations where there is no compelling argument for a change from general practice.

One thing I might worry about is the Dyneema bridles cutting through the nylon. In fact I’m not sure I’m entirely comfortable with this mixed materials approach. Not sure exactly why I say that, but my general fear of the law of unintended consequences is definitely aroused.

Perhaps the best bet would be to make the first section of the drogue in Dyneema too, which would solve your splicing problem. Not a fun suggestion, but the best I have.