There comes a final moment, when all of the food, fuel and water is aboard, the boat is ready to go and the goodbyes have been said. All the planning, scrutiny of the weather and last minute checks have been carried out, and there’s no excuse to linger a second longer.

It’s a delicious, calm, sober moment—the taking of the first step. And when it comes, we like to go quietly, without any fanfare and when no-one is looking if possible—it’s a very private pleasure. And so it was as we cast off from the fuel berth at Mindelo Marina, and set off to cross the Atlantic on the 20th of December.

We wouldn’t be following the celebrated trade-wind route to the Caribbean with most of our British compatriots, as (as usual) we were following the French route to Brazil with a smattering of Dutch yachts and others.

The Easy Route?

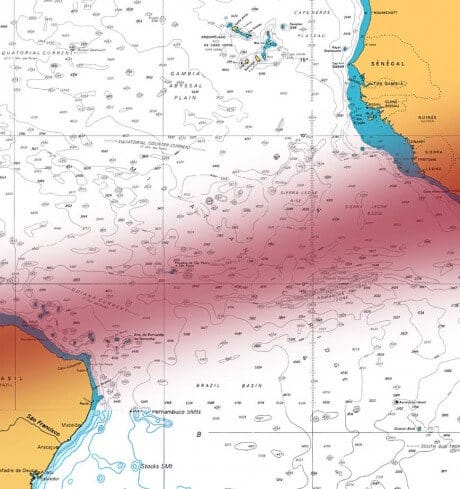

Red area is the average position of the ITCZ in January.

On the face of it, it looks a straightforward enough passage but, as we were to learn, it’s far more tricky than it looks on paper, and demands far more tactical planning than the run to the Caribbean, what with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and contrary ocean currents to negotiate.

The ITCZ has long been known to sailors as the doldrums, a band of calms, tropical squalls and torrential downpours that traverses the Atlantic along the Equator from Africa to the the East coast of South America, and has beset mariners in sailing vessels for centuries.

In December the ITCZ can be as much as 600 miles wide off the African coast, narrowing slightly in mid-Atlantic before widening again off South America. You can either choose to try and cross it at its narrowest breadth, or motor through it. The former is slightly easier these days as satellite telemetry available via the internet can predict the position and breadth of the ITCZ, whilst the latter relies upon you having sufficient fuel capacity and/or being deaf (to ignore the engine running 24/7).

Well, the latter was out of the question, as we don’t have the fuel capacity, and Pèlerin is a sailing vessel—we were going to do it the hard way.

Then there are the equatorial counter currents that precede the southeasterly trades that predominate south of the equator, slowing your progress just when you least need it in the region of 7°N to the Equator—painful.

Finally, in order to make progress south once you’ve crossed the Equator, you’ll likely be hard on the wind for at least some of the time in order to weather the easternmost extremity of Brazil, unless you’re heading for one the ports north of the Equator, or the Amazon delta. If you’re going south to the main cruising grounds of Brazil such as the Baia de Todos os Santos (Salvador) or the Baia de Ilha Grande (Rio) then the good news is that between December and March there should be northeasterly winds and a southwest bound current between Cabo Sao Roque and Cabo Frio to help you on your way, something worth looking forward to as you bash your way through the doldrums and onward.

Our Strategy

Firstly, we delayed our crossing until mid-December to allow the trade winds to become properly established and strengthen. It’s tempting to leave in late November to ensure Christmas is spent somewhere exotic, but the trades tend to be weaker and less reliable that much earlier. And as we planned to sail as much as possible, we needed dependable winds.

If you cannot, or are unwilling to, motor through the doldrums on the African side of the Atlantic (which has the benefit of allowing you to reach across to Brazil once in the SE trades), then you have to pick a meridian of longitude to cross, usually somewhere between 25º and 30ºW. Too far east and you run the risk of spending more time than necessary in the doldrums, too far west and you face an uphill struggle to climb south to your preferred destination. Alright if your boat goes upwind like a knife through butter and you don’t mind spending days on end on your ear—no thanks.

So we decided to hedge our bets and aim for a crossing at 27ºW, when, with a little luck, we wouldn’t be hard on the wind for too long before the southeasterly winds would start to back to east, then northeast as we clawed south to Salvador.

What Happened in Reality?

Click on photographs to enlarge.

The first few days were great sailing, basically because the second you’re out of the harbour at Mindelo you’re straight into the northeasterly trades at 20 knots plus. Pèlerin positively loves these conditions, and with the centreboard three-quarters raised we loped along making excellent progress, without any major effort on our part. In fact, we could easily have pushed harder, but we were following our usual policy of sailing conservatively during the first few days to allow us all to settle in to the rhythm of the passage.

As it was, the easy conditions and Pèlerin‘s downwind stability meant that after the first couple of nights we were all sleeping well, and our three hours on, three off watch pattern let us all get enough rest. For the next six days we held the wind from the northeast through baking hot days and starlit nights, broad reaching on port gybe. Daily checks above and below decks showed all was well, keeping maintenance to a minimum. We could stand a lot of this, we thought.

But all good things must come to an end, and we celebrated Christmas Day with squalls and occasional downpours (during Christmas lunch, of course). That night we had our first signs of lightning since departure, fortunately most of it high altitude sheet lightning, but as a taste of things to come it didn’t seem a good omen.

The wind steadily eased through the day, and as it wandered around the compass, it kept us fully occupied to maintain progress under sail. And for the first time, we had a cross sea, with the first of the southeasterly swell meeting the last of the northeasterly swell. By 1800 we were lurching around uncomfortably in what was left of the wind, with our course all over the place as we tried to keep Pèlerin pointing in the right direction—well, any direction, in fact—welcome to the doldrums!

I reckon that you have the Wichard bom-prevent installed ,same as I have,,I like it,,works great. What’s your experiance out there in the big swells??

Hi Conny

We like it a lot, especially when the boom is squared away on a broad reach or run, when it works as a downhaul, stopping the boom from rising or bouncing in the swell. The fact that they use a ‘springy’ technical rope means you can strap it down tight, whilst still allowing a little give, so that nothing is likely to be damaged.

But it’s not a substitute for a true preventer, in our view, and we always set up a proper fore guy when offshore – belt and braces maybe, but the possibility of an involuntary gybe in big swells and/or squally conditions is much greater, and the potential consequences far worse!

Best wishes

Colin

Congratulations on your crossing! Sound like you had an enjoyable passage.

We left a few weeks earlier (with the ARC 2012) and had LOTS of wind to St Lucia. 20 years ago we went from the Canaries to Fernando direct and had a similar sounding passage to you in the Doldrums. Thanks for bringing back memories!

Paul Shard

SV Distant Shores II – St Martin

Hi Paul

I think we did- but perhaps it’s still too early to say, as i don’t think I’ve entirely digested it yet! And Part II may throw more light on our crossing.

We haven’t given up on the idea of Fernando yet, as we plan to visit on our way North – it sounds a wonderful (if costly) place to visit. We have a planning meeting tomorrow to look at where we go for the next few months which will decide that one way or another.

Good to see you made your own crossing in good shape, and I hope you’re enjoying the Caribbean.

Best wishes

Colin

It was 1991 when we visited Fernando. Very dramatic and lovely but even then it was costly to visit as I recall. We anchored off the harbour (rolly) and paid per day. We were filming the spinner dolphins but that was also complicated. Not sure I would recommend you make the effort…

We have been enjoying the Caribbean and will take our time heading south from SXM checking out the anchorages around Martinique, lovely Dominica and the Grenadines.