One of the things that makes me crazy is offshore sailors who claim that getting rolled upside down is just a risk of being out there; yeah, I’m looking at you Don McIntyre.

The other, and related, thing than makes me nuts is that big waves, twice (or more) the size of the significant wave height, are popularly called “rogues”, with the implied assertion that they are very rare and and getting rolled by one is bad luck.

The efficacy of the Jordan Series Drogue (JSD) has been proved in countless deployments over decades, which blows both of the above out of the water, but still sailors go out there without a properly installed JSD and then whimper that they were unlucky when their boat gets rolled.

They were not unlucky, they were un-seamanlike.

We have an entire Online Book dealing with all of this, but it’s still worth publicizing the latest proofs of the JSD.

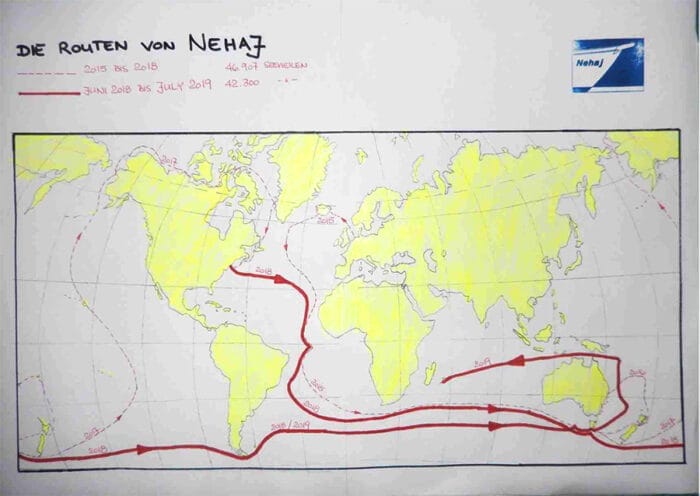

To that end, our friend Susanne Huber-Curphey has just completed her second La Longue Route (The Long Way) voyage in her Koopmans 39-foot aluminum cutter Nehaj.

For those of you not familiar with it, La Longue Route refers to a voyage made by Bernard Moitessier starting in 1968, and the book he wrote about it.

Moitessier, while in second place behind Robin Knox-Johnston in the Golden Globe Race, decided, after rounding Cape Horn, to keep on going in the Great South rather than turning north for Europe with a good chance of victory.

He then sailed across the South Indian Ocean for the second time before finally ending his voyage at Tahiti after over 37,000 miles of non-stop solo ocean sailing.

In 2018 Susanne entered a loosely organized round-the-world voyage to commemorate Moitessier’s from 50 years before, and like him she carried on after rounding Cape Horn for a second transit of the South Indian Ocean before finally stopping in Tasmania.

After many other amazing voyages in the intervening years, Susanne set out again in 2024 on roughly the same route and just completed it in New Zealand a few weeks ago.

Add the two together and she sailed 66,575 miles over 521 days.

Both Susanne’s La Longue Routes qualify as one of the great small boat voyages of all time, never mind both together, an achievement that leaves me in open-mouthed admiration.

Anyway, here’s the Tip:

Login to continue reading (scroll down). Paid membership required:

I’m also going to take issue with

“Significant wave height” is, by widely-agreed-upon definition, the mean height of the highest 1/3 of the waves. (Statisticians might also define it as four times the square root of the zeroth-moment of the variance spectrum, the distinction versus the first definition being insignificant to anyone without a Ph.D in statistics.)

If there is more than one wave train in the system, then there WILL be waves much larger than the significant wave height. Not “may.” “Will.” It’s right there in the definition of the term! These are not random or unpredictable. They are simple linear superpositions of ordinary waves.

Similarly, when an established wave system reaches a region with a contrary current, the waves will bunch up and get steeper. Again, these are not crazy unexpected out-of-control waves. This is just what water does, naturally, all the time.

Genuine rogue waves – overwhelmingly larger than the others in the system, and generally nonlinear in their tendency to draw energy from adjacent waves and concentrate it in the main one – do exist, and are dangerous. But the *vast* majority of “I got rolled by a rogue wave” stories appear to consist simply of being unprepared for the totally normal, totally expected waves that are statistically certain to occur within the weather formation in question.

Hi Matt,

Thanks for the corroboration. In the linked article on “rogue” waves I dug into a bunch of work done on wave height and found that the incidence of waves twice significant wave height was alarmingly high. Of course that does not take into account whether or not a specific wave will break, but still it’s sobering.

Thanks for the good article, John.

Hard to believe people still sail the oceans without having a JSD ready.

All the best from New Zealand, Nehaj-Susanne

Hello John,

Thanks for the interesting article and deep respect for Susanne’s

accomplishments. I was amazed by one picture in heavy weather sailing taken from the bow. What always caught my eye is the boat – Nehaj. There was once an article on Wilfried Erdmann’s page It would be great if we could learn a little bit more about this vessel.

Kind regards from the Basque Country,

Alex

Hello John,

lying a hull and running with exhausted crew are clearly bad, leaving us with drogue vs. sea anchor, and you indicate you prefer the former. victor shane’s drag device database ( https://dragdevicedb.com/) offers both counterpoint and support for your point in reviewing hundreds of cases…..In other words, when considering drogue vs. sea anchor reports and data he offers, I think that one cannot say one or the other is best without considering the boat and crew….His collated reports show that a sea anchor may be better than a drogue for a yacht that won’t track downwind unattended in big waves, as this amazing yachtswoman’s craft did, unless one has a very deep and experienced crew of helmsmen to keep the boat on course. On the other hand, a properly structured and equipped yacht (read uncharacteristically strong bow and cleats) with a sea anchor with sufficient and correctly sized parachute and rode (not too short, not too long, not to thick, not to thin, properly chafe protected etc etc!!! according to VS database) may do much better with an exhausted crew. At least that’s what the drag device database seems to show….In other words, if your boat will track down waves unattended with a JS drogue, that’s the way to go most likely; if it won’t then the sea anchor may be the only real option for a tired crew with a broach-prone yacht. only a test and practice will tell….unless you have a yacht listed in the drag device database…then you can learn from other’s experience.

I think you are mistaking the terms “drogue” and “series drogue”, as the two are related but still significantly different devices.

a drogue slows down the boat by several knots and, as you describe, is useful if the boat tends to sail downwind on her own merits. the drogue provides resistance to stern and keeps the boat from going too fast, potentially pitch-poling. there are many ways to make a drogue; a common one is a car tire with a bit of chain looped through it.

a series drogue does significantly more; it provides a smoothly-escalating amount of resistance depending on how much forward force is applied, and it stops the boat almost completely dead in the water, holding the stern pointed firmly backwards into the wind. the experience is a feeling almost more like a “rubber band” than a normal drogue… the more the strain on the drogue line, the more the resistance.

the reason I say this is that the first time I deployed my series drogue in ‘survival conditions’, about six hundred miles west of Hobart, Tasmania, it worked exactly as advertised, keeping my little 34′ sailboat firmly pointed downwind and only making about 1.5kn… it should be noted that per your description, my boat does not track downwind unattended. my little boat has a cutaway-forefoot full keel, and her rudder is quite far forward, so she turns quickly and easily (I say “skittishly” on my more pessimistic days), and she doesn’t much care for sailing dead downwind. google “islander 34” for a pic.

the second time I deployed my series drogue, in a strong gale (55kn sustained winds, max gust 71.2kn) about a thousand miles east of New Zealand last month, was a different story. I had noticed some fraying of the cones in the drogue, and had earmarked it for repair. for the first few hours on the drogue it behaved as expected, but slowly that changed, and by morning I was tracking dead downwind at almost five knots. I even experienced a couple of scary moments where a strong gust pinned my little boat over, with the wind at about 45° off the stern quarter, for a few minutes at a time.

when I retrieved my series drogue after this second experience, it came up quickly and easily, and I discovered that about three quarters of the cones had blown completely out. the benefits I was seeing from it were more akin to trailing warps than a well-designed JSD! I was still impressed that my boat handled as well as it did with a drastically-diminished drogue in play, but it was still a scary experience.

I’m currently in Tahiti negotiating with the French Polynesian customs agents to get them to release the package they have for me, a brand-new oceanbrake.com series drogue. I’m sailing for Hawaii shortly, on the edge of hurricane season, and I am fully convinced that this is by far the best way to endure large weather systems at sea.

ahh… a very important distinction. thank you for the clarification based on what amounts to an A-B test design after you lost some cones…much appreciated.

Hib Drew,

Good explanation, thank you. Sounds like you too really proved the JSD! I’m also sure that you will be really happy with the new one. Ocean Brake have done great work on making the cones more robust than the original specification.

Hi Ronald,

I don’t agree because I don’t think that tracking down wind has any bearing on whether or not a JSD works. Tracking is an issue when moving faster than with a JSD.

The boat is being held by the stern with a JSD and all sailboats and most motorboats are more stable when held by the stern than the bow. In fact this is one of the big advantages that the JSD has over sea anchors. Yawing is one of the biggest problems with sea anchors, just as it is when anchored.

Don Jordan explains this and even suggests that there might be benefit in anchoring by the stern in storms: https://jordanseriesdrogue.com/D_14.htm Also my first hand experience supports this.

I also explain the physics here as it relates to yawing at anchor, but the same applies with the JSD and sea anchors: https://www.morganscloud.com/2020/03/03/surging-at-anchor-the-theory-and-the-solution/

There are also a bunch more reasons why I prefer the JSD: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/sea-anchor-system/

The only time I think a sea anchor has any benefit might be with multihulls, and even there I’m not at all sure. More coming later in the week.

Hi All,

Does anyone know of any real good videos of a sea anchor deployed in a fully developed force 10 or above that shows the yaw of the boat and what is going on with the rode? The reason that I ask is that sea anchors and drogues fundamentally work on a different principle and I think this difference is very important.

The mechanism of a sea anchor is to attach the bow of the boat to a fixed object (parachute) by a spring (nylon line). Line does not make a perfect spring but it does return an awful lot of the energy that goes into it. This means that after a big wave when the line has stretched a lot, the boat will then move towards the anchor and tension in the line will decrease and there isn’t a lot of resistance to the boat moving forward until the next wave hits. If a big wave hits when the boat has moved forward a lot, the boat may need to move backwards from the anchor a significant amount before the tension in the line is high enough to get the bow pointing up into the wave and then drag it through the wave. Also working against you is the flow of water in the wave, this will add to the slack problem. How much the boat moves towards the anchor is a function of how much energy is stored in the spring and how much damping (energy removal), there is. If there is a lot of damping, then the boat will not move forward a lot and the tension will still be high when the next wave hits. If there is not much damping, the boat will move forward a lot leaving little to no tension in the line when the wave hits which leaves the boat vulnerable to being pushed backwards/sideways and even potentially rolled before there is enough tension to bring the bow up into the safe bow-on configuration. You can’t do away with the nylon line or the shock loads would be too high but without enough damping, it will cause a new problem. My interest in video is to see how much of a problem or not this is. All the videos I can remember watching are in sub gale conditions so not particularly relevant.

By comparison, the purpose of a drogue is to add damping. Many people even use dyneema line on their JSD which stores almost no energy so there is very little spring in the system. With very little spring and cones pretty close to the boat, the force in the line will increase very quickly pulling the stern into the safe orientation to the wave. Reports from users are that this happens quickly and in plenty of time to prevent the boat from being rolled due to being too broadside. There does appear to be some slack which can cause shock loading but this appears manageable.

In most engineered mechanisms, the key is to get the combination of spring and damper correct.

Eric

Hi Eric,

I don’t know of any videos shot in true storm conditions on a sea anchor and I’m guessing that they would not be that useful, even if there were, due to the flying spray. That said, over the years I have read most of the sea anchor accounts in the drag device data base and yaw back and forth is often mentioned as a problem, particularly on monohulls and even to some extent on multihulls lying to a bridle.

Bottom line, I think your point about the difference between spring and damping together with the fact that pretty much all boats lie more quietly when held by the stern because the centre of effort is forward of the centre of lateral resistance just makes the JSD a way better solution than sea anchors.

The other point is that the JSD is the only solution based on actual science done by an aero engineer rather than guess work.

To me anyway, while this debate continues to rage, in actuality it was settled years ago in favour of the JSD, both in theory and practice.

Hi Eric,

I think we might agree on most of this, but my limited experience might be relevant. I have deployed a sea anchor, twice, neither of them were in very heavy weather. One was a proper sea anchor, just to test it. I didn’t like the experience. Even in perhaps 20 knots of wind and protected waters it felt overwhelming and not safe to handle. The other time I rigged a small jib as a sea anchor on a race boat when we lost both rudders in a fishing net. I wanted to prevent that we hit land. This worked surprisingly well. According to the Danish navy (who later towed us in) we had moved less than 2 nautical miles in 10 hours.

The jib was “sheeted in” by the weight of a small anchor, so the forces were not very big. This was a Formula28 trimaran (8,5 meter long), (“XOZ”, related to the Exocet rockets) so extremely light (700 kg) and wide (6,4 meters), which makes the experience irrelevant for most cruisers, but as an emergency solution, for that boat, in max 30 knots of wind and less than proper ocean waves, it was near perfect.

Would I use this strategy in an ocean storm? Not if I had any other alternative… I’ve never tried a JSD, but I’m completely convinced that it’s the only right solution, almost always. The only exception might be when caught near a lee shore. Again, I think we agree on this.

I have once been in a storm when a JSD would certainly have been the right solution, but we didn’t have one and hadn’t even heard of it. This was almost 30 years ago, west of Portugal, in a TRT1200 catamaran, a very fast cruising cat. We had average close to 60 knots of wind and gusts much stronger with waves probably ten times the second biggest ones I’ve ever seen through 50 years of sailing. We handled it by fore reaching, steering the boat to avoid the breakers. Speed never below 10 knots and frequently well above 20 knots, with only a tiny storm jib up (5,5 square meters). We tried to keep speed as low as possible by zig zagging violently, also to create turbulence that would trip the breakers early, so they didn’t hit too hard.

The reason for going into detail is that I think it might be relevant to the question you ask, about stretch in a sea anchor tether. Since we didn’t use that, or have it, I can only speculate. With really heavy winds like this, when the air has loads of water in it too, the boat gets a constant heavy push downwind. It really feels like a physical wall of power leaning on you. It never lets go, not even in the very deep wave throughs. I’t clearly less there, but far less relief than I had imagined. It was enough to drive us at speed up the waves. Again, this is far from a normal cruiser, so not really comparable, but it might give some measure of variability of the wind force.

If I were to imagine hanging on a stretchy nylon line from a well set sea anchor, (I’ll never experience that, as I’d have a JSD), in that same situation, on a more normal cruiser, I can’t see how much slack could appear while the wind/water push is so continuously relentless. I imagine that there would be significant variation in the tension/stretch, but perhaps rarely any actual complete slack. The exceptions, if at all, I’d assume would be just leeward of the top of the waves, the breaking zone, where the boat would get the hardest blows and the wind also seems more turbulent.

I’d assume this is the worst timing for slack, so quite critical, but also that it might be pretty rare. With a more “normal storm”, this might be different. As mentioned, just speculations… My conclusion is that even if a sea anchor was performing perfectly in this setting, (it won’t, as it’s impossible to keep it always inside the waves and away from the breakers in such a chaotic and violent environment) it’s still a dangerously flawed contraption, for all the reasons mentioned here on AAC.

Hi Ronald,

We fitted a JSD for our relatively light Beneteau 473 to go offshore.

But we considered carefully a parachute anchor, having read the Pardey’s book “Storm Tactics”. Our 473 is pretty docile at anchor and I was confident she would lie well to one.

Plus our Cat 1 surveyor was a staunch believer in parachute anchors having been saved by one in an unseasonal cyclone during one of his two circumnavigations under sail.

Reading from this site, the Pardey’s book Storm Tactics, Heavy Weather Sailing and the drag database left me undecided. I even costed both options. What it came down to was our large semi-balanced spade rudder with no skeg and a composite rudder shaft.

With a sea anchor AND JSD your boat will surge many metres during the passage of a breaking wave. With a JSD and rudder lashed amidships, our boat surging forward will do zero damage, as we have many times surfed at 15 knots going forward as a gust hits.

With a parachute anchor surging many metres backwards at speed, I feared the rudder would take enormous repeated forces due to being semi-balanced. And eventually damage the bearings, especially the lower one. If the lower bearing collapsed, then it wouldn’t be long before the free hanging rudder would break off at the top of the rudder blade. And even if the rudder bearings held, the rudder could snap off at the shaft if the boat surged back at a wide enough angle.

Lastly, in the South Pacific at least, we most often have more than one wave train direction in a gale or storm. A JSD will deal with this well, I wasn’t sure a parachute anchor would, even using the Pardey’s unique bridle method.

Br. Rob

Hi Rob,

Lots of good points, thanks.

One thing to clarify though. I think it’s important not to think about the Pardey bridle method and sea anchors as being the same or even related. The Pardey bridle is actually a variant on being heaved-to with sail up and uses a much smaller drogue than lying to a sea anchor and, if memory serves, in later years Larry thought that the drogue could be even smaller. Our own Galerider off the bow technique seems to support this.

Anyway, the dynamics of lying to a full on sea anchor are, I think, quite different since all sail is down and the boat is, because of the size of the sea anchor, effectively anchored in the ocean.

Agreed John, at that stage we hadn’t decided which storm strategy to employ, but definitely saw them as three distinct options, two using a sea anchor – thanks for the catch. In my defence this was about 10 years ago that I was asking you lots of questions!

I don’t remember Larry opining the parachute drogue could be much smaller, using their bridle / hove to technique, but agree with your thinking as it’s the slick to windward that creates the artificial reef to windward that Lyn and Larry attested to.

But they had a boat that naturally hove-to – a friend of mine sailed to NZ in a Herreshoff that he owned for many years and claims its best point of sail was hove-to.

But I do remember reading the Pardey bridle’s weakness (and to a lesser extent the JSD) being a relatively high rate of drift (2 knots)? And so needing sea room to execute – they had anxious times off the East Coast of Queensland in a cyclone, creeping ever close to the outlying reefs.

The parachute anchor’s strength is the low rate of drift.

We ended up with both a JSD for storms, and a “Sea Brake” drogue for hoving-to in near gales plus emergency steering option.

Hi Rob,

I agree that there are drawbacks to the Pardey system and also with the point that their boat is perfect for heaving-to. And yes the JSD does give us a bit of drift, but then again in these days of better forecasts there’s not a lot of excuse for getting caught in a storm less than 50 miles from a lee shore. So, to me anyway, the well known problems with sea anchors (detailed in the linked posts) make the JSD a head and shoulders better alternative, except possibly for multihull. More coming on that.

We have an excellent Oceanbrake JSD in dyneema but have not had to use it yet – after reading this we will get it out and practice deployment and recovery asap!

Hi Mike,

Good plan. Retrieval is the tricky one, but we have full instructions on several methods in the linked Online Book.

Another mega-experienced offshore sailor who gives convincing testimony on the JSD is Randall Reeves of the “Figure Eight Voyage”. I think he is a subscriber to ACC and he may choose to pitch in himself but when he was in Halifax a few years ago I had multiple chats/interviews with him on his heavy weather tactics. And it was the JSD to rescue when the situation demanded. His issues as Mike suggests, and would certainly merit practice, were retrieval, chafe and damage to his wind vane steering. All resolved with experience with the unit.

Hi Rich,

Absolutely. I spent some time with Randall when he was in Halifax and learned a lot of cool things. Nice guy too:

https://www.morganscloud.com/2019/07/12/series-drogue-learning-from-randall-reeves/

https://www.morganscloud.com/2019/06/08/a-chat-with-randall-reeves/

Thank you John. Despite the compelling article and book chapter, I’ve been reluctant to use a JSD on account of my boat being one of those modern performance cruisers with an open transom. I fear the lay of the boat under the restraint of a JSD is inviting a wave into the cockpit, smashing the wash-boards and flood the boat. I have consequently practiced heaving-to under reduced sail and sea anchor to stay in the wake. Would you consider this to be the best option, given the boat design?

Hi Antony,

That’s a hard one to answer with any certainty, however if we really study Don Jordan’s work we find that the risk of being “pooped” in the traditional sense of green water boarding over the stern when lying to a JDS is low, and might even be non-existent. My own observation over many years seems to support this in that I have never been on a boat that was “pooped”, rather if green water comes aboard it does so over the lee quarter as the boat partially broaches and therefore I’m not sure an open transom makes a lot of difference.

If you do decide to go with the Pardey system make sure you don’t confuse that technique with lying to a sea anchor, see my comment in answer to Rob, and particularly don’t use a full size sea anchor, but rather follow Lin and Larry’s book to the letter.

Thank you for the great advice! Best.

Hi John,

I just had the chance to have a chat with Susanne yesterday in Marsden Cove where she’s just taken a decent break. The sailing she does is truly impressive and her approach to it or the why she does it are truly unique. Nehja splashes in 2 days.

She said we should have a chat about the utility of the JSD on a heavy displacement boat. She said you had a heavy displacement boat and know a ton about JSD. She is certainly right about that.

SEAMER clocked it at 30 tons on the lift today… The guy says his lift is said to be off by about 1.5-2 tons, meaning we would be more around 28. Empty of fuel, water and provisions and everything (when we bought her, she was empty from all the belongings of the prior owners), she was at 24 tons. Before today, we had guessed 27 tons. We were not too off.

As a storm solution, we currently have a 5 cone (18 inch wide) very improvised drogue, the 5 cones are distributed along about 500 ft of nylon, 3 strands, rope, with 15 ft of 3/8 chain at the end. It’s on a long bridal (about 40 ft). It’s very stretchy. As a matter of fact, we removed the cones and towed a sailboat over 220 nm off the coast of NZ with that set up, minus the cones, last month. The stricken sailboat had lost it’s rudder. We sure did witness the stretchiness of that line under load.

SEAMER is heavy, 56ft long, 42ft at the waterline, 13.5 ft wide. In nasty weather, she handles fabulous. We are sure we could, or let’s assume we will for the sake of the discussion, encounter worst seas than what we’ve put her through so far.

We have serious sailing ahead of us, think going East from NZ to FP to eventually reach Patagonia and get back home on the Atlantic ridge, South Georgia, Tristan du Cunha, Santa Helena and so on until NS and eventually Qc. Some passages will be very long and certainly won’t be covered by any forecast made at departure.

In my mind, we would be safer with a JSD. But Susanne, an exceptional sailor and the goddess of JSD deployment, sorta put some doubts in my head about ordering one. So, to come down to business, how big is too big for a JSD? Is there such a thing? I’m asking on here in hopes that your answer can also be beneficial to other readers that have big boats.

Best,

Marie

Hi Marie Eve,

As long as the JSD is appropriately sized it should be fine. You will probably want to use Dyneema to keep the weight under control. (Stretch is not required for the JSD to work well.)

Ocean Brake and Ace Sailmakers, do a good job of building them and show prices for boats up to 70,000 lbs: https://www.oceanbrake.com/pricing http://jordanseriesdrogue.com/D_4_m1.htm

And you will find a lot more in our Online Book: https://www.morganscloud.com/category/storm-tactics/online-book-heavy-weather/

Definitely have a read through the book as there are things to know, particularly about deployment and retrieval.