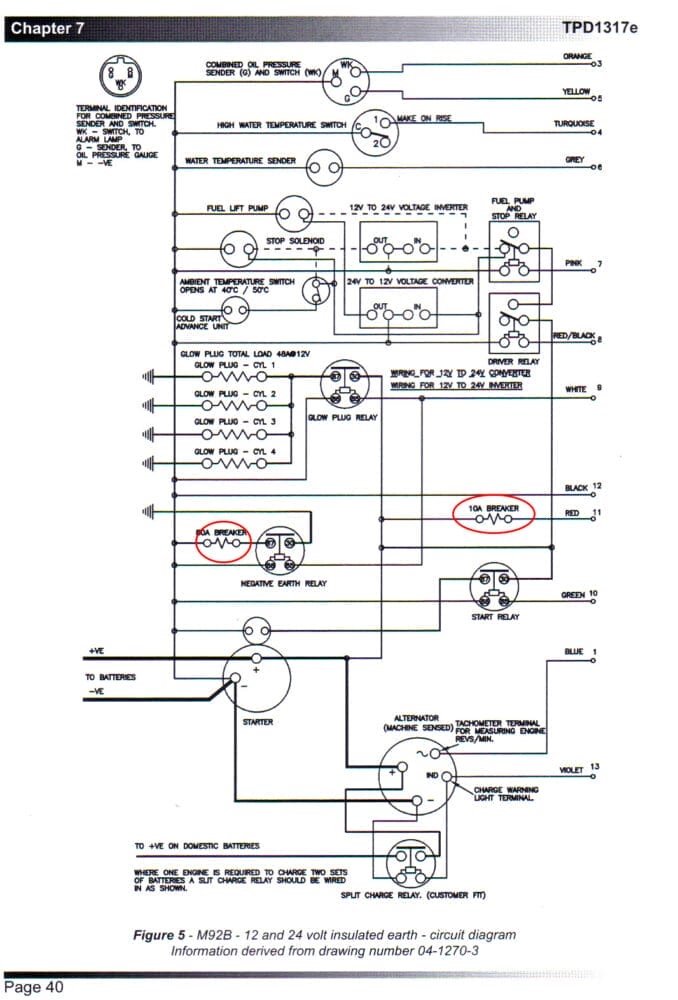

If I had read the above headline prior to buying our J109, I would have assumed that the author was fear mongering. Sure, many engines are not fused at the battery as we recommend, but both the unlamented Cummins and much-loved Perkins M92B on our McCurdy & Rhodes 56 had fuses and/or breakers to protect the harness wiring from a meltdown in the event of a short—see below.

So I was, to borrow that lovely English expression, gob smacked to find that the harness on our 2004 3YM30 Yanmar engine was not protected, other than a single fuse in series with the idiot lights on the panel and the sensors connected to them.

At first I assumed that Tillotson Pearson, builder of our J/109, had fabricated the harness themselves. After all, the whole boat when it left the factory in 2004 was a marine electrician’s nightmare, and not even close to ABYC compliant—I fixed that over the first winter.

But no, one look at the engine manual (see above) told the tale, and that further makes me think that there may be thousands of Yanmar (and other) engines out there waiting to burn some unsuspecting owner’s boat out from under them.

The Dangers

Overly dramatic? Nope, this is seriously dangerous shit. Let’s run though the issues:

- Any time the master switch is on, the engine harness is connected directly to the positive post of the start battery, even if the ignition switch is off.

- Even a small lead-acid battery can produce several hundred amps, enough to turn wires white hot if short circuited.

- Even if the start battery has a fuse added, as we recommend, it won’t protect the harness because said fuse must be big enough to pass starter loads, and so will not blow before the small wires in the harness melt.

- The engine harness is draped all over the engine block, which is connected to the negative pole off the battery.

- Engines both get hot and vibrate, a perfect modality to cause the insulation on the wires to fail.

- Any wire that touches the block will cause a short and likely melt, all the way back to the battery.

- Engines use…diesel (duh), which when combined with melting wires equals…fuel fire.

- ABYC standards call for wires and fuel lines to be well separated, but in the real world they are often close together, or even in the same bundle.

- In the latter case, as it was on our boat, that should be fixed too.

- Engine harnesses are often routed around the engine box that’s often made of wood, which, after a few years, will likely be impregnated with oil and fuel residue. A fire looking for a place.

- Many wires of the engine harness are often routed for many feet over combustable materials on their way to and from the panel and ignition switch.

- A short in the wrong place could cause the entire run to go red hot.

Put it all together and this is a recipe for a fire that could easily be out of control in minutes.

And this is not just theory. I spoke with a diesel mechanic I respect and he confirmed that he has seen at least two Yanmar engines with melted wires in the harness.

The Fix

The good news is that an unfused engine harness is fairly easy to fix, as long as we can read a simple circuit diagram, like the one above, and apply some basic fuse wisdom as follows1:

Hi John,

Thanks for a timely reminder, and knowledge that was more unknown to me than I’m comfortable with. I already put a fuse on the positive battery cable at the start batteries som years ago, but at the time I was questioning the rest of it, feeling there should be more, but then letting it be with that, as one does…

We have older Yanmars, installed 1997, 3GM30, 27 Hp, two of them. There were zero fuses anywhere in the system, until I added the above mentioned battery fuses. I think the engines were installed by the previous owner himself, as it looked like not professional work, but I think he used a factory new harness.

I’ve already changed some of the wiring, but will do a total renewal this winter. I think most don’t need that, as long as this issue with missing fuses is fixed. The group of sailors present here are probably generally more competent than most. Still, even then we may treat the engine room as a mystery room, where only professionals can do anything good. It doesn’t deserve that. I’d even say this task seems relatively straightforward. At least on our older style engines.

Hear hear Stein 🙂

Well John. We just have two small petrol 20 HK outboard engines on our 12 meter catamaran and I didn’t really think much of this issue…

Guess what – I discovered there are som oopsies with our installation

So I guess this makes your point and you win the argument again John 😉

Fortunately I have some electrical fuse work to put on my to do list now. Could have been worse 😀

Hi Gismervik,

I don’t regard this as a win for me, but rather a win for you and Stein in being open minded to the problem and committing to dealing with it.

One point on your excellent comment: You don’t want to be thinking about the output of the alternators when specifying over current protection. Rather what matters here is the gauge of the wire and the maximum that the battery can produce when fully charged and shorted out. The point here is that when adding OCP the battery is the current source, not the alternator. Even the pros, and sometimes engine manufacturers, get this one wrong. More here (#3): https://www.morganscloud.com/2022/03/19/8-checks-to-stop-our-dc-electrical-system-from-burning-our-boat/

John, the subject of OCP non-compliance is one about which I am passionate, it can never be discussed too frequently, and its violation is the most common electrical defect I encounter in the vessel inspections I conduct.

It appears those fuel lines were installed by the builder, that rough cut zip tie doesn’t look like Yanmar material, and if so, they (the builder) also would have supported the wires to them, which is a violation of ABYC Standards. If these were added by the builder that is egregious, but not the fault of the engine manufacturer. If Yanmar zip tied wires to a fuel line, something I’ve never seen from them, then that would be a clear safety issue and again an ABYC violation.

If the wiring leaves the engine, then the onus switches from the engine to the boat manufacturer.

By no means am I diminishing the importance of this message; however, ABYC Standards have an exemption for OCP where wires are part of an OEM engine wiring harness, which does not leave the engine, the assumption being that the engine manufacturer has engineered the harness to be routed around the engine with the proper support and chafe prevention.

Additionally, starter positive cables must not make contact with the engine in any way, that is an ABYC requirement, and that’s on the boat builder as they install the power supply to the starter.

Here is the relevant exception (italics mine) “E-11.1.2 This standard applies to:

11.1.2.1 alternating current (AC) electrical systems on boats operating at frequencies of 50 or 60 Hz and less than 300 V, including shore power systems up to the point of connection to the shore outlet and including the shore power cable, and

11.1.2.2 direct current (DC) electrical stems on boats operating at 60 V nominal or less.

EXCEPTIONS:

1. Any conductor that is part of an outboard engine assembly and does not extend beyond the outboard engine manufacturer’s supplied cowling.

2. Engine manufacturer supplied engine management systems and their associated conductors.

In my nearly 40 years in this business, I have never seen a fully OEM harness short and catch fire. Do unfused positive wires anywhere aboard make me nervous? Can you add OCP? Absolutely. Should you add OCP in the above example? Most definitely.

I believe all positive DC wires should be OCPd at the source, with perhaps the exception of starter cables, but that’s a debate that’s been covered.

Many engine manufacturers use a fuse or circuit breaker on the engine, to protect wiring that leaves the engine and travels to the instrument panel. My only gripe with many of these is they are often well camouflaged and almost never labeled, so when a instrument panel and key switch go dark, few users know where to look to resolve the issue.

Modern electronically controlled diesel engine manufacturers frequently leave it to the builder to supply power to the engine ECU, and they almost always recommend this power be derived directly from a house battery, and most, at least of late, call for OCP, regardless it’s needed for ABYC compliance. In that case, again, it’s up to the builder to install OCP (I prefer CBs because they can be reset, if you only have a handful of spare fuses and you are troubleshooting a short, that can be a problem). I have seen ECU supply wiring installed without OCP, but only rarely, and by the lowest quality builders.

The little black caps that come with the Blue Sea surface mount breakers are, IMO, inadequate, the ring terminal is still exposed, these should be fully booted.

“A 150-amp fuse at the point where the feed from the alternator joins the battery cable.”

Do you mean at the battery, or starter post? If this wire is OEM and does not leave the engine (yours goes to the battery, I understand that, however, for stock alternators the cabling goes from the alternator to the starter, and is generally accepted to be covered by the above exemption, a handful of builders include a CB, CAT being one of them, most do not), i.e., it is connected to the starter pos post, as many are, it may not need OCP for ABYC compliance (see below). If it leaves the engine, it must be OCPd where it connects to the battery or the vessel’s positive bus. Because alternators are self-limiting, they again may not need OCP at the alternator, for ABYC compliance.

Here’s the ABYC exemption language…

Overcurrent protection is not required in conductors from self-limiting alternators with integral regulators if the conductor is less than 40 in (102 cm), is connected to a source of power other than the battery, and is contained throughout its entire distance in a sheath or enclosure. Overcurrent protection is not required at an alternator if the ampacity of the conductor is equal to or greater than the rated output of the alternator.

Again, an incredibly important subject well worth the coverage.

More on over-current protection here https://stevedmarineconsulting.com/over-current-protection/

Hi Steve,

Thanks for the added info. I also read your article, linked at the end. There you mention OCP of starter motor cables, and that you understand how boat builder liability could be an issue, like if the motor needs to be started in a critical situation from a battery with a low charge level. The lower Voltage will cause higher Amperage, which could blow a correctly sized fuse and turn the situation into an accident.

I understand how boat builders would fear blame in such situations. However, wouldn’t it be possible to get past that problem by using an oversized cable with a fuse/circuit breaker to fit that cable? If that combo is sized for a low Voltage start, the fuse should not be a problem? Indeed , it should improve the chances of a successful start, since the voltage drop from the battery to the start motor will be less. A bigger cable and fuse will bring more cost, but that seems negligible in this context.

Another option would be to use a smaller cable/fuse and then make it very easy to reset. My solution until now is neither, but rather a good awareness of starter battery conditions, as well as a twin engine installation (catamaran) with independent systems, and a reasonably accessible switch to start any engine from any battery.

Hi Stein,

With an adequate sized engine start battery fuse there is pretty much no chance of it blowing and preventing an emergency start with the size of engines that most of us have: Rod over at Marine How to explains why here: https://marinehowto.com/battery-banks-over-current-protection/

Also, I have been fusing my start batteries for over 40 years—had a hell of a time finding the fuses and holders back then—and have never blown a fuse while starting, and that includes a 120 hp 6 cylinder Cummins.

Hi Steve,

Lots of interesting points. However, those exemptions are another of the many parts of the ABYC requirements that are, in my view, just wrong and the result of industry insiders sitting on the committees that set the requirements and therefor campaigning to weaken the said requirements in dangerous ways to make things easier for builders and to reduce liability for past mistakes.

To me allowing an unfused harness because we assume that it will be properly insulated is an insult to electrical common sense. Fuses are there to prevent fires when insulation fails, and an engine that vibrates and gets hot is perfect place for that to happen.

As to whether this is Yanmar or TPI’s fault, I don’t really care but Yanmar must know that the panel will be placed some distance from the engine so the circuit diagram should show fusing.

Also, I think whether or not you have seen a melted harness is not relevant. We both know that there are way more boat electrical fires than their should be and after a bad fire caused by this problem there is going to be no way to accurately determine where it started, particularly since often the boat will have sunk. Also, as I say in the article, I talked to just one diesel mechanic and he had seen two harnesses with melted wires on small Yanmar engines. That’s two too many.

The bottom line on this is that builders, installers, boat yards, and owners, will make mistakes, but if the basic fusing fundamentals of protecting all wires at current source with a proper sized fuse are followed those mistakes will not cause fires. Or to put it another way, fuses are there because people make mistakes, so to say a fuse is not required because we assume that the engine manufacture will get insulation perfect is a complete, and inexcusable, logic fail on ABYC’s part, particularly since that harness can be damaged in so many different ways (a careless foot comes to mind) over it’s many decade life.

Anyway, it would seem that we are fundamentally on the same page given that you write: “Should you add OCP in the above example? Most definitely.”

John:

Let me take your comments one at a time, and let me say, this is your site, I respect that, you are of course more than free to say what ever you believe is true and accurate, and helpful to boat owners; other than electrocution protection, no electrical subject is more important than OCP. I’m a firm believer in vigorous debate when it comes to technical subjects, it tends to yield the best results for all parties.

JH: “However, those exemptions are another of the many parts of the ABYC requirements that are, in my view, just wrong and the result of industry insiders sitting on the committees that set the requirements and therefor campaigning to weaken the said requirements in dangerous ways to make things easier for builders and to reduce liability for past mistakes.

To me allowing an unfused harness because we assume that it will be properly insulated is an insult to electrical common sense. Fuses are there to prevent fires when insulation fails, and an engine that vibrates and gets hot is perfect place for that to happen.”

SDA: I sit on those committees, and I have experienced exactly this, fellow committee members who work for manufacturers who are very good at one thing, saying “NO”. It’s a battle in almost every case to get a change through the committee process that may cost builders even an additional $10. Having said that, ABYC Standards are based on improving safety, if actuarials, if boats were burning up because of faulty wiring harnesses, they would react with a revised standard, and engine manufacturers have an incentive for their engines to not catch fire. Having said all that, fuse holders are cheap, I would include them, however, I don’t condemn an engine that does not have them on an OEM wiring harness because I would have no evidence to back up such a condemnation.

JH: “As to whether this is Yanmar or TPI’s fault, I don’t really care but Yanmar must know that the panel will be placed some distance from the engine so the circuit diagram should show fusing.

SDA: You squarely laid blame at Yanmar’s feet, implying thousands of engines may have the same issue, when I believe this is a boat builder error, and it sounds as if you may agree. Still egregious, however, it may only be present on your vessel, or a previous owner may have even done this for all we know. Although it does not diminish the importance of OCP, there is a difference when you are pointing fingers at an engine manufacturer. I agree, there are too many boat fires, but none that I have seen were the result of a Yanmar wiring harness. If this was an OEM harness issue, I suspect we’d be seeing way more.

JH: “Also, I think whether or not you have seen a melted harness is not relevant. We both know that there are way more boat electrical fires than their should be and after a bad fire caused by this problem there is going to be no way to accurately determine where it started, particularly since often the boat will have sunk. Also, as I say in the article, I talked to just one diesel mechanic and he had seen two harnesses with melted wires on small Yanmar engines. That’s two too many.”

SDA: Why are the mechanic with whom you spoke comments relevant but mine aren’t’? I have seen thousands of engines in my nearly 40 year career, and my work involves scrutinizing them for faults and potential faults. I’m not doubting he saw these melted harnesses, but without more evidence it’s impossible to say if they were OEM, had the engine overheated, was the engine disassembled and wiring harness supports removed and not replaced (I encounter this often), and so on. Additionally, if a fire starts in an engine compartment, even if the vessel is a total loss, we still usually know where it started. Boat US claim statistics indicate that 32% of fires are DC electrical in origin (the largest single cause), while in only 7% of the cases the engine is the source. Again, I believe the OEM wires on the engine are low risk, however, once the boat builder makes modifications or attaches wires, that’s where the risk goes up substantially, and boats only become more electrically complex every year.

JH: “The bottom line on this is that builders, installers, boat yards, and owners, will make mistakes, but if the basic fusing fundamentals of protecting all wires at current source with a proper sized fuse are followed those mistakes will not cause fires. Or to put it another way, fuses are there because people make mistakes, so to say a fuse is not required because we assume that the engine manufacture will get insulation perfect is a complete, and inexcusable, logic fail on ABYC’s part, particularly since that harness can be damaged in so many different ways (a careless foot comes to mind) over it’s many decade life.”

SDA: Again, no argument from me on the importance of OCP, however, the example you used, including wires zip tied to fuel lines, I believe isn’t an engine manufacturer issue, and yet you condemned Yanmar for this, as well as omitting fuses where you believe they should be included. You and others are free to add OCP, but we simply aren’t seeing engine harnesses catching fire, on Yanmars or other engines, and they aren’t in violation of ABYC Standards. When a new standard is proposed, ABYC committee chairs are quick to ask, why are we doing this, do statistics support a change, or was there just one, maybe high profile, failure driving this? Engines and their harnesses should be inspected regularly for chafe and wear. Do engine manufacturers make mistakes? Yes, just two weeks ago I encountered a small gauge, unfused wire connected to a starter positive post that was chafing against the starter housing. The wire was too short to have a fuse, it was within the first inch of wiring after the ring terminal, so the only way to protect it was through proper routing and support. This was on a new engine, I would share a photo if I could do that here.

JH: “Anyway, it would seem that we are fundamentally on the same page given that you write: “Should you add OCP in the above example? Most definitely.”

SDA: We are, I love OCP;-) My gripe is in tarring Yanmar when they don’t appear to be in violation of ABYC Standards, stats don’t support condemning them, and this was probably a boat builder or previous owner induced defect. Now, you can take aim at ABYC. In fact, the electrical standard is up for review right now and anyone can make suggested changes. If you believe they are flawed, I encourage you to weigh in and make your voice heard. I can show you how to do this if you are interested.

As far as the unfused starter cable is concerned, I would not try to discourage anyone from adding OCP, provided it is done properly and does not elevate the possibility of a failure to start. Unfortunately, circuit breakers for this application are large and costly, so in most cases it has to be a fuse, which is not quickly or easily replaced. I suspect this will eventually become an ABYC requirement, although boat builders will fight it tooth and nail.

For ABYC compliance, the maximum allowable number of ring terminals per stud or fastener is 4.

Hi Steve,

I think we are making this more complicated than it needs to be, me included. I see this very simply:

Therefore, in this case, Yanmar are just plain wrong. And if ABYC enables that wrong they are wrong too.

You stated in your 5 point list of where/why you added breaker/fuses, you added a bussbar, “… to avoid contravening ABYC standards by connecting more than 3 wires to a stud.”

I thought the number was 4?

Hi Rick,

You might be right, I was writing from memory, although that memory says three…but then I’m 73!

Anyway, regardless of what ABYC says, I really don’t like seeing a bunch of terminals on one stud, so when I’m wiring something I aim for no more that three, and prefer one or two. If nothing else a lower number makes it easier to trace circuits when trouble shooting.

Hi Rick,

I checked, you are right, it’s 4, I will change it. Thanks

Switching to the automotive field for a moment:

Do we remember how car fires used to be a fairly common thing that happened all the time? And do we remember how the insurance industry told all the OEMs to smarten up, figure it out, and fix it?

One of the changes they made was to start fusing *everything* at a very granular level and wrapping all wire harnesses in good quality chafe protection throughout. Whereas the cars on which I learned to drive had just a handful of 15A fuses with several things daisy-chained from each, plus a bunch of stuff tied directly to the battery, my current cars have fuses for every tiny motor, every actuator, every sensor, every group of lamps. Many of them are only 1A or 2A fuses.

Not coincidentally, car fires went from being an “oh, yeah, that just kinda happens now and then” thing to an “if this happens to two out of 150,000 cars in a year we’re ordering a recall” thing.

On our boats, the statistics by number sold are comparatively sparse, but the risks – and the solutions – are similar.

Hi Matt,

I wondered about that when I was answering Steve’s comment, but being a total non-car-guy I did not know enough, so thanks for fielding that. Sounds like we are still in “oh, yeah, that just kinda happens now and then” around boats and that ABYC needs to smarten up!

Hi John,

This is a good reminder and unfortunately a sore point with me and our Westerbeke 38B Four installed in 1999 (repower by PO). When we got our boat, I studied the schematic and found that it has 2 circuit breakers that mostly cover the circuitry on the engine. When I looked at the engine, it actually took a few minutes to find the breakers just as Steve mentioned and there was a lot of wire before them without OCP. But the real issue is that the official wiring diagram was not a good reflection of the harness on the engine which really looks like a factory harness. The previous owner did the engine swap himself and I know how he normally wires things and none of this looked like that, it really looks like a factory harness. The biggest discrepancy is that the alternator output goes through the harness on a 10awg wire which is not in the diagram and it has no OCP.

Looking harder at our alternator setup, I found that there was a 10awg positive wire going through the stock harness and a 12awg ground wire going from the alternator to the block (isolated chassis alternator). On this engine, the stock alternator is a 50A unit but the engine came to us with a 90A unit which was an option so I don’t know if the engine ever had the stock unit or not. The previous owner was clearly aware that the wiring was not up to the alternator and added an 8awg wire running back to the starter connections. By doing this, the wiring harness was now being fed from both ends making the breakers which had protected more than half the harness not protect much at all. Also, up to 90A was being pumped through a 12awg cable, its insulation showed that it was barely hanging on.

The stock battery cables including cables to the engine were 2awg welding cable with no OCP.

Battery cables and alternator are now appropriately fused, the wiring harness is single ended again and has a fuse at the start so that in conjunction with the breakers provide pretty good protection although not perfect as I would have to cut into the harness in a not great place to make it really right. Our surveyor said nothing about any of this but I did spot it pre-purchase so was able to change it right away. I can see how this would easily not be corrected and that is a little scary. I am a reformed lazy fuser on battery cables as I used to work on a lot of boats with big engines where a cold engine start would blow a fuse on a 4/0 line but in truth most sailboat engines are small and very easy to properly fuse.

Eric

Hi Eric,

That’s indeed a scary situation, and I fear all too common, particularly since we had an identical situation on the alternator, only a bit worse in that someone had disconnected the larger added cable.

Far too many people will just graft things onto an existing system without ever stopping to fully document what’s already there.

That’s sometimes ok for simple branch circuits, but never for anything that touches the core of the system.

If you take the time to draw the schematic on paper, neatly and correctly, then errors like this *almost always* become obvious before they’re made.

2008 Yanmar 4JHE – No fuses

Installed in a 1987 boat. Likely not the worst fire hazard aboard but I’m working on them and will investigate how to best protect the Yanmar harness as well.

Hi Gentry,

Thanks for the report and good on you for checking and taking on the issue. I sympathize since I too, when we bought our J/109 was faced with so many potential fire starters that I had to prioritize.

Thx for this article. And very timely as this has been on my list of things to do. I also have a Yanmar (3JH5E) and your analysis and updated schematic has saved me some work. Also, thank you to Steve D and everyone for the thoughtful comments. Keep up the great work!

Hi Michael,

Glad it was useful, thanks for the encouragement.