Some time ago I wrote an introductory post about my involvement with an entry in the forthcoming update of the Golden Globe Race (GGR).

I’m sure that many of you must be wondering what has transpired since then, how the entry is going, and what lessons can be learned from all of the effort involved in bringing the boat and skipper safely to the start line in June 2018.

Well, there has been good news and bad news.

First the bad news: our skipper Fabrizio Ladi Bucciolini suffered a serious back injury during the delivery of the boat to Europe.

Now the good news: he had the common sense and decency to realise that (as a result) he had no option but to withdraw his entry. This was a bitter pill for him after so much hard work, financial investment, planning and dreaming, but it was undoubtedly the right call.

To have continued in the knowledge that the injury was likely to recur (and at the worst moment, no doubt) was not something that could in any way be countenanced by any of us involved with the entry, especially his family. A terrible shame then, but a decision that took guts and integrity, for which Fabrizio earned great respect from those of us close to him.

But the lessons learned? Wow, where to start. And many of them have direct relevance to anyone contemplating a long-term voyage to remote areas or who through personal preference or budgetary restraint choose an elderly boat for their voyage. Stay with us, as it’s going to be a very interesting ride…

Finding a Suitable Boat

Choosing the right boat was the first task, one that was dramatically narrowed down by the short list of permissible boats. The only boats allowed to enter are long-keeled boats of a broadly similar design style to Robin Knox-Johnston’s original GGR race-winner Suhaili, and equipped to a fairly basic standard in modern terms.

Limited Choice

The organisers, quite sensibly, realised that whatever the merits of wooden boats, it would be hard to discover enough boats in that material or from that era that would be fit to form an entry of thirty boats. Effectively, this left heavily-built series production boats built in GRP as the only possible options.

Initially, my instinct was to opt for the boat with the finest lines, which was in my view the Rustler 36. These lovely Holman and Pye yachts were designed in the 70s as a cruiser-racer and are known to sail well.

Carry a Load

But Fabrizio pointed to the short waterline and the lack of sail area as penalties that might mitigate against the boat. Thinking about his comments and the unique nature of the GGR, further downsides became apparent, as it gradually became clear that we would need to think about this race in completely different terms to a ‘round the cans’ event.

So working our way through the list of boats, Fabrizio and I agreed that we might be mistaken in simply selecting the nimblest boat. An easily understood analogy for this race might be that of the tortoise and the hare: some of these boats will be at sea for 300 days or more, so even if the skipper lives very frugally on dried food for the duration, food alone will still add up to a substantial amount of weight.

Add to this all of the sails, spares and stores that must be carried, and it becomes obvious that the boat must be a good load carrier to cope with such a hefty payload. So we felt one of the heavier displacement models with fuller underwater sections might be a better choice, especially early in the race when the load carried will be greatest.

First Choice

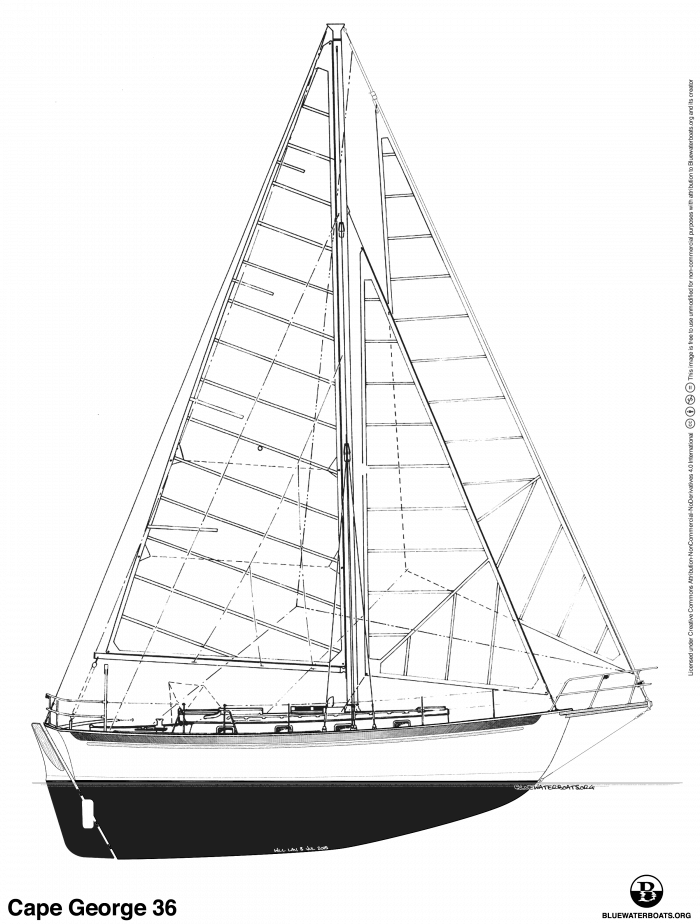

Eventually, we alighted on the handsome Cape George 36 as our preferred option. Like Suhaili, this is a design with very direct lineage to the early days of yachting, both boats being based on the lines of venerable William Atkins designs.

With a long waterline, sweet underwater sections and a decent sail plan, she looked like she would be easily driven and also well balanced, this latter point being highly important as the only self-steering system allowable would be some form of wind vane. So the search began, with a basic budget of US$150,000 to find a good, sound basic craft to work on.

Here we ran into the next hurdle:

Nearly every Cape George 36 on the market differed substantially from the original design: at some stage over the years the boats had acquired a taller rig, longer bowsprit, modified bulwarks and so forth, and all had timber decks that the organisers frowned upon.

Dealing with the rig issues was less of a concern, as we’d already accepted that whatever boat we found, we’d probably have to upgrade the rigging, but to completely renew the entire rig because it wasn’t to the original specification would be a major blow.

Here, no doubt, you can (as we did) begin to hear the sound of the piggy bank being emptied. Add to that the cost of replacing the decks with an agreed solution that would satisfy the race organisers? Ouch!

So, in the end, despite the fact that we found two very nice boats for sale, we had to pass on them both and expand the search.

Initial Lessons Learned

Another learning experience for us: most of the potential boats are over forty years old, and not all of them have had the best owners. It began to sink in that it was a very good thing that we had started our search early, since finding the right boat was not going to be simple.

Also, we realized that we might be looking at a major rebuild, not a refit, to end up with a boat fit to enter the race.

Meanwhile, 29 other entrants were also going through the same process and snapping up the best boats they could find. The field was narrowing daily.

The One

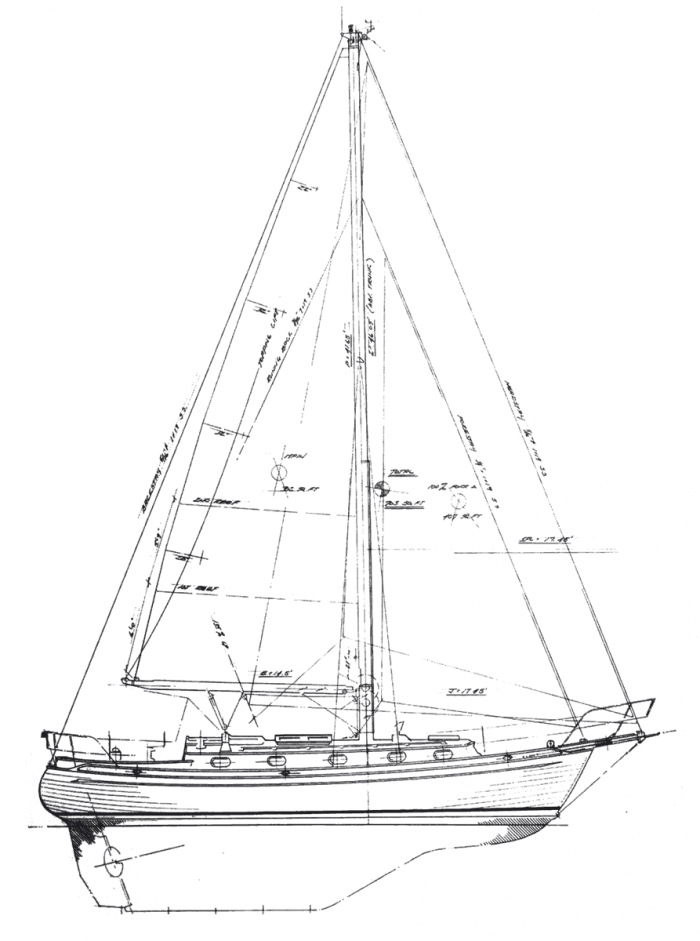

Eventually Fabrizio found a design he really liked the look of, the Bob Perry-designed Tashiba 36. Many of these were of a more recent vintage than some of the boats we had already looked at (which was a plus), and there were quite a few on the market in the USA, so this seemed like a good option to explore.

Eventually, we narrowed it down to one boat that clearly had been looked after like a favourite child and, following a very favourable survey, it was decided that Jessie Marie, built in 1987, would be our entry.

A Huge Job

Whereupon the work began in earnest.

Anybody who has ever fitted out a boat for long distance sailing knows that there is an immense amount of work involved in making the boat ‘ocean ready’, and Jessie Marie, lovely, well-cared-for boat that she is, proved to be no exception. And this was just for her to cross the Atlantic!

Of course, some items were to be installed in preparation for the race itself—a wind vane, solar panels, wind generator, storm jib and trysail, for example—but others were the sort of age-related repairs and renewals that we all face at refit time.

Not that that was much consolation, the list was already long and the bill was growing, too. And there would be more to come when she arrived home in Italy to undergo a full pre-race refit.

A Test

Eventually she was ready, and in early June the lines were cast off in Jacksonville, Florida and Jessie Marie was on her way. Two bad gales on the way to Bermuda gave her a real battering and Fabrizio was glad that they had bought decent storm sails at this stage rather than just prior to the race.

Sensibly they lay hove-to through the worst hours of the gales and the boat felt comfortable and safe throughout. As might be expected, some minor damage was suffered, but all of the new gear stood up well, and it was a relieved but satisfied crew that entered Bermuda to sort things out for the next leg.

So Far, So Good

Sometimes it’s as well to really test a boat early on to find out what she can handle, and this first voyage certainly did that. Undoubtedly it’s better to identify any weaknesses at this stage while close to shelter and repair facilities rather than in the wastes of the Southern Ocean.

Disaster Strikes

After a crew change, Fabrizio was once more on his way. The leg to the Azores went smoothly, but it was the final leg from the Azores to Gibraltar that was to prove his undoing. During a week of beating into the northeasterly trades, his lower back gave out and, with no other option but to plug on in cold, damp and rough conditions, he could get no respite.

It became clear to him that the likelihood of similar conditions (or worse) in the GGR whilst on his own would simply be impossible to countenance. You could say that a dream was smashed, or take the more pragmatic view that it’s better to quit while you’re ahead and choose another battle.

After all, there will always be other dreams, and Fabrizio had achieved no small feat in bringing his small boat home through 5000 miles of challenging Atlantic conditions. It could have been far worse. And he still has a fine, proven boat in Jessie Marie to enjoy with his family and friends.

Coming Next

But the race goes on, and in the next instalment we’ll look at what it all cost to get to this point, what boats the other entrants have chosen, and how the race is shaping up—for truly, it’s a major event with (as we learned) valuable insights for anyone looking to take an older boat ocean sailing.

Hi Colin,

Thanks for the update and thank Fabrizio for his effort, but, more importantly, for exhibiting good seamanship in deciding not to continue. Very often, good seamanship (maybe even good judgment in general) is backing away from challenges or changing course or changing plans. Too often, the disappointment in making this tough choice is transformed into a feeling of failure, rather than disappointment, a lousy and inaccurate transformation, but one all to easy to make.

I do not follow races such as these in general, so I was unaware of the stipulations attendant on boat choice. It was wonderful to see boats being chosen that espoused a good offshore pedigree. I think good boat design has evolved since that era, but they are clearly the forerunners of the modern era of seaworthy off-shore boats for couples and families. Too often these days, I believe the sailing public is poorly educated as to what a good offshore boat should be like.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick

Turning back has never been something I’ve learned to like, even when I know I’ve done the right thing. I’m like a bear with a sore head for a few hours, but I get over it. But for Fabrizio to run his back on a dream that he had poured so much into is on a different scale altogether, and, as you say, speaks volumes for his judgment, especially bearing in mind his family, friends and supporters who were behind him. That he did the right thing for those who mattered most shows the calibre of the man.

And it will be interesting to see how these older designs will perform in what will be (to say the least) challenging conditions. This is a major experiment with significant numbers of participants using a similar style of boat and it will indeed be interesting to see how they hold up in the face of the Southern Ocean.

Best wishes

Colin

Running off in today’s faster boats has become a preferred tactic, but the older full keelers are less handy in this regard. Conversely, however, they are arguably better at heaving to. The difference between the late 1960s and now in terms of heavy weather management are drogue devices like the JSD (as opposed to trailing warps). I wonder how this would play out in this race? Will JSDs be “allowed”? They hadn’t, to my knowledge, been invented yet at the time of the original race, but then, neither had sat phones, GPSes and plotters.

I agree in every particular. Seamanship is also knowing when to continue sailing means abandoning seamanship.

Hi Marc

and that will always be the case – as Joseph Conrad once wrote ‘ships are alright; it’s the men in ’em’.

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

Interesting thoughts about the boat selection. Load carrying capability certainly seems like it would have to be important. Having never sailed the proposed route, I wonder whether it is a windy enough route that you would want a boat that could be pushed hard in comfort with somewhat fuller ends for high hull speed. One thing that I think is interesting in the shorthanded offshore racing is that now they are putting more value on keeping the sailor comfortable with a sort of pilothouse. The Tashiba 36 certainly looks like a nice boat, I daysailed on a 40 once and remember liking it.

It is too bad about Fabrizio’s back, that must have been a very hard decision to make. I know that I am stubborn and would have really struggled if it had been me. I sail our boat solo about 10 days a year, usually when my wife is traveling for work. I find it interesting that most people who hear about it ask how I can handle the boat by myself but ignore the true danger which is when something goes wrong such as if I ever became incapacitated. A few weeks ago while out for an overnight, we had a boat drag to a position too close to us at night during a wind shift and we elected to move. While reaching down to open the seacock for the washdown pump, my back gave out. The next morning we were able to sail back to our mooring normally but if I had been alone, I think it would have been a trying experience just to motor back. Having an issue in the middle of an ocean is a truly scary thought if alone.

Eric

Hi Eric

we were looking for a boat that would be easy to handle and capable of good average speeds, also kind to he crew – we think the choice that was made was a good one.

I have just been laid up for over a week with sciatica and couldn’t walk more than four steps for several days. Bed rest and painkillers helped me back on to my feet, but the what if I’d been in the Southern Ocean? It doesn’t bear thinking about…

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

Ouch, sorry to hear about your nerve issues. Hopefully it all clears up soon.

As an aside, several years ago I met the doctor who emailed the instructions to Viktor Yazykov about his mid-ocean elbow surgery. He had quite the story to tell.

Eric

Sad to hear that he had to abandon the race, but admirable that he makes the hard decision, not the tempting one. I’m not sure if would be as wise.

Also Interesting to see how you were thinking and kind of testing my own opinions against that. I think I agree about load carrying ability being important, but I think that ability to keep a decent speed in all types of conditions, strong wind and big waves, light conditions, upwind as well as downwind. None of the competitors will be able to surf huge distances in short time, like modern racers can, so specialising in downwind speed probably won’t give enough advantage if it means loosing on other angles…

Even though it’s inspiring to think about how it would be if were to participate in the race myself, I’m happy that I won’t. It’s going to be brutally uncomfortable, and I think I’m too old to have fun with that. 🙂 A friend of mine through many years is participating though, and he’s about my age, so I guess he’s tougher. His name is Are Wiig. He’s Norwegian, like me. He has many years of experience with solo ocean sailing and he’s a true wizard with fixing anything on a boat. That might be quite an advantage… He’s been sailing his Golden Globe boat for a year or so. I don’t remember the boat type, but he’s pleased with it.

Since I’ve moved to Amsterdam and he’s busy with preparations, I’m rarely in contact with him, but I can try to get some updates now and then and report them here.

Hi Stein

It may well be that a good all rounder will surprise us all – there’s no perfect boat in the fleet as far as I can see.

And I very briefly met Are at the launch of the Race and he impressed me with his experience and sense of proportion – I’m sure he’ll do well.

Best wishes

Colin

Hi

Are Wiig is going to participate in Olleanna , a OE 32. Scandinavian double ender designed by swedish Olle Enderlein.

To night he started at Hvasser in Oslofjord to set a singlehanded record along the Norwegian coast up to Nordkapp. You find more information about this in Facebook, are sailing.

aresailing.no

I briefly considered taking part in the Golden Globe Race, and thought out what was important to me, and what was not, for such a voyage. As I have sailed every part of the GGR route single-handed in vessels of 30-35 ft, most legs more than once so I believe I had a fair idea what is important, at least to me. Although I decided against entering the race because I did not like the media circus aspects of it, here are my thoughts for undertaking such a voyage.

Important:

1. A strong hull and deck together with hatches that can withstand a great deal of punishment. Most well built yachts can be brought up to this standard fairly easily. If the hull and deck are inadequate, it will probably take more time and money to remedy than is justified; look for another boat (which is of course what is what eliminated the Cape George from Colin’s consideration)

2. A strong rig, ideally low and easily handled. The rig should be able to lose any one of its support wires without losing the mast. For example, if a backstay parts while running before force 10 or 11 (which is when it is most likely to do this) the mast should not fold over the bow. There are numerous ways to make a rig this strong, but a prerequisite is a keel-stepped mast. Oversize wires to eliminate or reduce metal fatigue and doubling of any critical wires (twin backstays in a Bermudan rigged vessel for instance) also helps. Mast fitting and chain plates must be massive as they cannot be easily replaced at sea. The outer forestay of a (true) cutter does not have to meet these criteria as it is only there to support a sail. The loss of the outer forestay is merely a nuisance as it is the inner forestay holds the mast up.

3. Every wire in the rig must be able to be replaced at sea by one person from materials carried aboard. Wedge lock terminal fitting and allow this, swaged fittings do not. A suitable supply of spare wire and fittings should be carried as it is neither expensive nor heavy. Indeed, I think any serious voyaging vessel should carry these spares, no matter where bound. I would normally expect to rig a temporary Dyneema shroud or stay to support the mast after a wire failure until I could fit a more permanent replacement. I find it much easier to work up a mast when single-handed using rock climber’s harness and ascenders (Jumars or similar) than trying to work from ratlines or mast steps.

4. The vessel must have an easy motion. Apart from being kinder to the crew, it is MUCH easier on the rig. A vessel with its ballast concentrated deep in the keel has a much quicker, more violent motion that stresses the entire rig. Ships in the days of commercial sail typically carried about a third of their cargo high in the tween deck to ease their motion and slow their roll period. This was not for the comfort of the crew (though it undoubtedly had that effect) but for the security of the rig. The frequent rig failures of the single-use, throwaway long distance ocean racers is probably as much due to their violent motion caused by carrying their ballast in a deep, central bulb, as to their under weight, under strength rigs.

5. Everything inside the vessel secured so that it remains in place if the vessel is knocked down. Far too little attention is paid to this is most yachts. It is difficult enough trying to pump or bail out a vessel after a serious knock-down without the interior being a morass of floating and submerged gear, wet food, books and the like. It is extremely unlikely that any electric pumps will be working at this stage, nor is it likely that the engine (if carried) will start to run engine mounted pumps. It is going to be buckets and hand pumps, and with any significant amount of water in the hull, the free surface effect makes the motion wild. It is difficult enough to bail out a great deal of (perhaps oily) water without the complication of swilling flotsam and jetsam.

Unimportant matters included:

1. I do not believe load carrying capacity is particularly critical. The weight of food and water required for such a voyage is less than 1 tonne (1 kg of food plus 2 litres of water per day for 300 days). Most 32-35 ft boats can carry this easily, especially as they can leave most of their anchor gear behind, together with dinghies and the like. A system to catch water is worthwhile but should not be relied on in the Southern Ocean. The rain down there is generally mixed with too much spray to be potable.

2. Windward ability is not critical. It is only on relatively short sections in the NE and SE Trades of the Atlantic that the ability to sail close to the wind is an advantage. I would much rather a strong, easily handled rig that is comfortable downwind at the cost of spending a couple of extra days in the Trades.

3. An engine is scarcely worth having on such a voyage. I intended to remove the it and leave it ashore awaiting my return to Europe. Apart from eliminating the drag of the propeller, the weight of the engine and its fuel can be usefully replaced with potable water. It also means that if the vessel is knocked down, the vessel is not left with a thick, extraordinarily slippery film of emulsified oil sloshing around the interior and covering every surface. The mess this makes is indescribable.

Route:

The passage south in the Atlantic at the beginning of the race and north again at its end are straightforward. Cross the doldrums close to the African shore southbound and do not alter course to round the Cape of Good Hope until well into the Westerlies, probably south of 40°S. Undoubtedly there will be some heavy weather on this leg, but it is unlikely to be prolonged and the weight of the seas is far less than in the Southern Ocean. Any vessel having trouble in the Atlantic is not going to last long in the Southern Ocean.

The Southern Ocean is likely to weed out most contenders. Heavy weather is frequent and the weight of the seas down there has to be experience to be appreciated. The leg across the Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean will be made in late southern winter and early spring when the gale frequency is high. There is the additional issue of turbulent currents south of the Cape of Good Hope. However once clear of that area it is possible to head north to better weather (perhaps as far north as 39°S), but this risks losing the Westerlies.

The passage around Cape Horn will be in mid summer when the weather is at its best, or more accurately, least bad. Of course as is no option but to go south of 56°S to get around Cape Horn (and preferably 57°S to avoid Diego Ramirez and the off lying banks), some heavy weather is inevitable.

Once around Cape Horn and having South America to windward, the trip north should be simple enough, but of course the yacht’s gear may be getting a bit tired by this stage. Cross the doldrums close to Fernando de Naronha, stand north it through the NE Trades with the wind a point of two free, through the Variables as the wind allows until the Westerlies are found to carry her on the final leg to Europe.

Hi Trevor,

Nothing like your voice of experience to interject reality into the requirements for a successful voyage in difficult conditions!

As the builder of one of the two Cape George 36’s that were considered for the Globe race, I’d like to correct a couple of misconceptions.

I recently went over the one that I built with a fine toothed comb prior to what was intended to be her 40 year re-fit. The engine had died from lack of maintenance/ use, but apart from that she was in close to the same condition as on the day she was launched. With the addition of the kind of ultra-strong rig you suggest, she was structurally ready to leave on a circumnavigation. The finest materials available– Port Orford Cedar, air dried teak, epoxy and silicone bronze everywhere in place of crevice corrosion-stainless steel have a completely different life expectancy than a production boat with a balsa core deck and polyester resin/glass like the majority of the boats approved for the race.

Far from having “an inadequate hull and deck” , the Cape Georges have a massively strong deck and cabin beam structure with epoxy laminated beams covered by marine plywood plus 5/8″ of teak structurally fastened to the beams. Far stiffer and stronger than a balsa cored deck. The hull itself is similarly overbuilt, and all tankage is integral to the keel, resulting in a double bottom just below the cabin sole for the full length of the boat. Underneath the integral tankage is 10,500 # of lead, which not only allows her to carry a big rig, but combined with only 5′ of draft gives her the soft motion that having the ballast nearer the roll center favors.

Hi Richard

There was nothing we didn’t like about the Cape George 36 (as I think you know). The problem we had was finding once as close to a ‘standard’ version. It was also true that the organisers didn’t like the wooden decks, which was a major worry and potential cost to change. She remained our preferred boat, buy it just wasn’t to be…

Best wishes

Coliun

Hi Trevor

there’s so much that I agree with in your comment, much of what Fabrizio and I had discussed during the initial stages of choosing the ‘right’ boat. It should be required reading for any entrant in the GGR.

There’s no doubt in my mind that this will be a real race of attrition, and will test the competitors to the maximum, let alone the boats!

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Trevor,

thanks for a real world founded comment, makes for really interesting reading, especially for an owner of an oceangoing 33ft steelboat. My boat has a deck stepped mast and I often wondered how a mast break could be prevented if one of the capshrouds should part. I never heard about your concept of ” the rig should be able to lose any one of its support wires without losing the mast”, although it makes a lot of sense. Do you have a suggestion how I could forestall a mast break in the event of capshroud failure ? I have an inner and outer forestay, double back stays, two pairs of lower shrouds, one pair of capshrouds, one pair of spreaders with no rake aft, masthead rig.

Hi Hans.

Firstly, a big thanks to Trevor for a very interesting comment! I’m way less experienced than him in that type of sailing, but I’ve experienced a falling mast almost 20 times through the years, so I’ve got some opinions about it. All those masts were on racing boats in heat, most of them were totally extreme boats, where things break every race, about half were just testing how light it could be done, so it’s a very different world, but still…

My interest now is long distance cruising, so I naturally agree with a lot of what Trevor says, but I’m not sure if it’s possible to have a rig that is reasonably efficient, and also absolutely cannot fall. Too much weight and windage in the rig will also compromise safety. I think it’s possible to get fairly close, though.

Most of my mast loss experience has been with deck stepped masts, but two with keel stepped ones, on monohulls. A keel stepped mast is more supported in the lowest part, meaning that it will not as easy deflect there, but there are easy ways to get the same effect on a deck stepped mast. If a cap shroud breaks, there will be zero difference in survival chances between the two.

On your rig, I’d think the only way to get more safety is to make double cap shrouds. I doubt if I’d do that. I think I’d prefer overly strong components and frequent inspections. Your configuration is probably already very good.

In general, I have a feeling there might be two very different strategies that may both give good rig safety. One is to make a very strong rig with as much redundancy as possible in its components. I think I’d choose carbon mast, twin mast head forestay for hooks (no furler), cutter stay lower down, possibly a loose baby stay. Two spreader pairs (not aft raking), shroud wires maybe not terminated at the spreaders (not sure), double aft stays, check stays for deployment when needed.

The other strategy is rather extreme in the opposite direction. Maybe more a mental experiment than a ready solution. Make a very simple and very light rig that probably won’t break if it falls and that can be fixed and raised again at sea. This strategy is most likely not suitable for normal cruising boats. It’s still worth noting that a number of the fallen masts were extremely light rotating wing masts made of carbon (one was 15m/50feet long, 50cm/2 feet wide and mast weight was 40 kilos/88 lbs). None of them were damaged by the dismasting. Rather, the fall was sometimes good because it prevented the whole boat from disintegrating from way too much power.

I think wing masts are a very bad idea on most more normal boats, but the same rig structure can be adapted to some types of cruisable boats. I’m thinking of making something like that…

I have what I believe is a compromise solution: a deck-stepped, double-spreader mast with 12 stays/shrouds (four uppers, four lowers, double backstays to the quarters and staysail and foresail/jib stays), all mounted in a metre-tall tabernacle. It’s a steel boat; the tabernacle is essentially a three-sided box with a keeper pin at the foot and pivot pin near the top of the tabernacle so that the mast may be lowered aft over the pilothouse roof for service or for doing canals, etc.

I’ve had people stop by the dock to ask to have a closer look, so I feel it has some merit. I’ve had no sense of problems in heavy weather with flexing or pumping of our mast.

Hi Marc.

Your solution sounds interesting, but I think I don’t quite understand the spreader and shrouds part. I assume the four upper shrouds are not parallel? It would mean extra safety for the mast top, of course, but have the feeling you mean something else…?

I would also like to be able to lower and lift the mast without external help. Since I now live in Amsterdam, it’s quite often a useful feature. A lot of boats here, especially traditional ones, have systems for this. Tabernacles are by far the most used system, often with a lifting boom and a system at the bow. I wanted to make a system for it on the cat we bought a year ago, using the main boom as a crane, but decided to leave it for now. Such systems do add weight and complexity, in some cases also some vulnerable structures. With a heavy aluminium mast, as we have now, on a light catamaran, I think we’re better off without it.

Also, even with such a system, most modern rigs need a lot of preparations and disassembly first, then assembly and tuning for getting the mast down and up, so it’s either way not a quick task. I think most boats are better if they are kept as simple as possible.

Stein, the four upper shrouds are indeed parallel. The mast is secured in its tabernacle by a retaining pin on the forward edge of the three-sided “box” of the tabernacle. The pivot pin is able to be lifted via two rings welded to screws and nuts; these allow the entire mast, when the turnbuckles are freed and the mast is secured with halyards, to be lifted enough to pivot backward. it is a fairly elegant setup the original designer created. I happened to remove the mast today for winter storage and it is fresh in my mind. When I consider the trouble of putting myself to the top of the mast, or hiring a mast crane for canal travel (common in the middle of North America and parts of Europe) I do not find it too onerous a task to lower the mast aft. It stays “pinned”, after all, to its tabernacle and is safe for calm waters.

Hi Stein,

wow, 20 mast “downings”! Not sure if I would still be sailing with that sort of experience. I haven’t found any better way to secure rig integrity than the one that you descibe: good and strong components to begin with, frequent thorough inspections and renewal of wires every few years. Thankfully, on a small boat like mine, this doesn’t break the bank. And I completely agree with Trevor’s suggestion of using wedge type terminals (Norseman in my case) instead of swages.

Hi Hans.

He he. I understand your scepticism, as did some boat owners one year when the mast fell on three different boats that year. One a bit dated 34 foot IOR 3/4 Ton ocean racer (rod shroud broke in pressed terminal under top spreader), a Formula 28 catamaran (lower headstay assembly came apart in a hard landing at well over 25 knots speed, no damage) and a trimaran in the same class, (experimental mast setup not able to take the load upwind. complete boat as sailing 600kg/1320lb, 7,8m/25ft wide, main sail sheet tension 2 tonnes plus. Mast folded. Not strange). All these during races. I felt a bit jinxed, 🙂 but only the last was influenced by me, my flawed design.

But the average (with more than 40 years sailing) has been more than two years between each incident, which is entirely acceptable, considering the number of hours on the water per year, the type of boats and the way they are pushed, especially during testing of new concepts. It’s never nice to lose the mast, and can be flat out dangerous on many boats, but it’s still mostly a different story with this type of sailing. There were a lot more of other types of breakages. Mostly details, but every race evening meant some hours of repairs and/or improvements.

As a bottom line, I feel I’ve learned quite a bit about how forces are generated, how they distribute in various structures, what is strong enough and what isn’t. I’m more skilled and less naively optimistic now. Engineering is absolutely necessary on sailboats, but hands on real experience like this, and like so many on this forum has, can spot problems or possibilities professional engineers don’t see. I’ve seen happen it lots of times.

Interesting. The boat beside me is a Mumm 36, a relatively uncommon design, and they lost their mast surfing at 14 knots in 30 knot winds last week. It was a 23 year old mast; they do not find it odd to have lost it and little other damage was done. The owner speculated that they got “out of phase” with the waves and the wind and this put unusual “pumping” stresses on the mast, when broke at the deck fitting.

Dear Trevor

A very interesting analysis, which made me wonder if there are any production boats of this size which would meet your criteria. The second thought which occured to me related to your point about ballast. This might be one reason that the theoretically “unsuitable” French aluminium centreboarders, most I think with internal ballast, have such a succesful record of high latitude voyages. At any rate, your analysis of the route and the difficulties to be encountered ought to be on the race website!

Yours aye,

Bill

Hi Bill

as the co-owner of an ‘unsuitable’ French aluminium centreboarder with many miles under my belt aboard her and similar designs one of the major pluses is undoubtedly the very gentle motion – they all have a nice soft ride that is easy on the crew, the rig and the gear. It’s also the case that these boats are now arguably the ‘weapon of choice’ for high latitude sailing expeditions the comfort factor (along with strength and safety) are definitely contributors to their popularity for this type of sailing.

Best wishes

Colin

Our first cruising boat was a Bob Perry designed, Taiwan-built, Baba 35, very similar to the

Tashiba 36. We sold her in the UK in 2014. The new owner was planning to enter the Golden Globe with her but had to give up his place when he couldn’t raise the required funds. We are now on our second cruising boat after owning the Baba and sometimes we wish we hadn’t sold her. We did our first long ocean passage in her, 51days across the North Atlantic to Europe and she looked after us well. What a great boat!

Hi Ann

the Baba 35 was also on our list of possible boats, for many of the same reasons as the Tashiba 36. As for the new owner withdrawing due to the costs, as we learned ourselves during the purchase and prep of a good boat, the numbers can rapidly grow. For at least some of the original entrants (and maybe some more yet) this has proved to be too much, for all of the reasons I’ve outlined here and in Part II (still to come). Old boats, new boats – it really doesn’t matter, skimping on cost and therefore potentially safety isn’t an option given the scope of this event.

Best wishes

Colin

You say you eventually settled on the Cape George 36, however I notice the Cape George isn’t on the list of approved boats (the Cape Dory 36 is on the list, but I don’t think you mis-read/typed when you wrote this article), were you, Colin, anticipating it being allowed on request due to it meeting the requirements? I see the organisers say they will consider other boats if they meet certain criteria and you send a request.

Hi Justin

the latter was the case – we believed the boat could be eligible and made the application, but there were concerns as there were a number of different forms of construction used (e.g.decks etc) and the organisers were concerned about that. In the end we couldn’t seem to find a way around it. I actually looked at a Cape Dory 36 but it was a long way from what we needed work wise, so we kept looking.

Best wishes

Colin

Hi All after being brutally belted for 3 days voyagiging up the western australian coast, I was smashed against some rigid furniture & fractured arib. As a novice sailor Iwas in pain & was nearing my tolerance level. My skipper came below & I asked her in desperation ” Is this as

bad as it gets”. To this she just erupted in uprorious laughter & told me this was nothing ! Strangely this gave me confidence. I immediately knew that the boat would be fine. It was me who was the weak link. That night I had to make a decision. We all know what it was We have no choice. Meanwhile the boat never uttered a sound of complaint ! Cheers

I was lucky in a similar situation to only purple my shoulder trying to put on pants in a V-berth in five metre seas which had turned the boat into a funhouse. I haven’t had a hit like that since high school rugby. I soon picked up that there’s no shame in crawling to the companionway if it gets you to the tether in one uninjured piece. And yes, the boat was fine.

Dave, Great comment. Welcome to the club of those who gather, and continue to gather, wisdom from offshore sailing. Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy