Going long-term cruising is a big deal in so many ways, not least in terms of the personal element. Judging by the many happy couples we meet cruising the oceans it’s an ideal life for some. But we’ve also met couples where one clearly loves sailing and the life that goes with it, while the other partner is, well, less convinced. Sometimes it seems to work—just—whilst at others it’s clear that it isn’t going to work and it just can’t last.

Lou and I had met on one of my shark surveys—she had never been aboard a yacht before, yet within five minutes it was clear that I was going to have a fight on my hands to get the wheel back from her. With some people it just clicks, in more ways than one.

Several years later, happily settled together, the crucial moment was coming up—would we go for the big decision, pool our money and build a boat to become our wandering home, or just stick to cruising around our beloved Hebrides?

Time To Front Up

As I was coming to the end of my career as a working skipper, and Lou had gone freelance, part of the decision was already made. But the elephant in the room remained—were we ready for it?

Lou, now with several years experience working as mate aboard our survey yacht, certainly felt so. But we both knew that whilst that had been challenging at times, it was essentially day sailing with others aboard to assist. The question of the transition to the longer haul and coping entirely on our own still remained to be tested.

So rather than run the risk of discovering some way down the line that we hated the life we agreed to put ourselves through a ‘crash test’ first. We picked on one of our bi-annual delivery trips between the west of Scotland and Cornwall, with just the two of us aboard, as a suitable proving ground.

Forever Changes, my trusty Frers 39, we both knew well and loved dearly, but she was essentially a working boat, with few concessions to comfort and no autopilot.

To overcome that latter deficiency we had already re-fitted our Monitor windvane, although we knew from previous experience that it would be of little use in the enclosed waters of the Irish Sea, where the shifting winds due to land effects meant endless corrections to the vane to keep the boat on course. But it was better than nothing.

And What a Place to Sail…

Ah, the Irish Sea. A nasty, narrow, shallow piece of water with ferocious tidal gates at each end, where the relatively sheltered inshore waters meet the might of the Atlantic.

I’d done this trip dozens of times before in a variety of boats big and small, in just about every configuration—non-stop, up the coast of Wales, down the Irish coast, in and out of just about every port of refuge—and the one thing I did know about the place was that, as the old Spanish proverb says, ‘whichever route you take there is a league of bad road’.

Tactically, this is one passage you have to get right. The currents are so strong that to make any real progress towards your destination you have to carry the tide with you, but if the wind is against the tide (as it always seems to be), well, you’re going to get a battering. And if you’re thinking of trying to make ground to windward against the tide, forget it—you’ll be going sideways at best.

For it to be an enjoyable and smooth passage, you need a good forecast, a capable boat and a determined crew—and more than a little luck. Fun, huh?

And as we were going to be doing this at the beginning of April, we knew that we had every chance of facing some really grim weather at some stage of the voyage. Short days, long nights, cold and wet.

We reckoned if we could hack this one, get home in good shape and remain on speaking terms, anything else would be a walk in the park.

Carpe Diem

So we made the long haul north in a van full of gear and got Forever Changes ready and launched in Loch Creran late one bitterly cold spring afternoon. The last of the sun’s wan rays reflected off the snow-capped mountains around us, and off we went—immediately. This is the kind of passage that demands that if the forecast is favourable, you just get going.

First stop was at Dunstaffnage in the pitch dark to fuel up in the morning—tired, cold, apprehensive, but elated to be on the move at last.

The weather forecaster’s cheery voice predicted light northeasterly winds with fog patches, so we were up and off as soon as the fuel was aboard. The sun was out, on one of those unique west highland mornings, when the visibility stretches the imagination and you feel you could just sail on forever. Until you run into thick fog that is, as we did as we raced down the Sound of Luing a few hours later.

Now, of course, the one thing that wasn’t working when we left was the radar. The radome had been damaged while the mast was down in storage, a fact we hadn’t been aware of until we came to put it back up. So there was no time to repair it, but we consoled ourselves that if you wait until everything is working, then you’ll never leave the dock.

As it was, we were approaching the one ‘busy’ stretch of this passage, close to the entrance to the Crinan Canal. But this early in the season there was hardly likely to be much traffic—was there? So we crept inshore to avoid any chance encounters, only to narrowly miss the only other boat out on the water, who had exactly the same idea. I don’t know who was the more shocked, but Lou just laughed it off as if this was a sort of everyday occurrence around here. I sincerely hoped it wasn’t…

Finally the fog lifted, and we were off again, sharp into the first and last westerly breeze of the entire voyage, down to the lovely island of Gigha just as the sun sank into the sea. Time for a quick snack, then straight to bed to be ready to face a 5 o’clock start. Typical delivery: perfect weather, ideal opportunity to visit a delightful island, and we’ve got to keep the pedal to the metal.

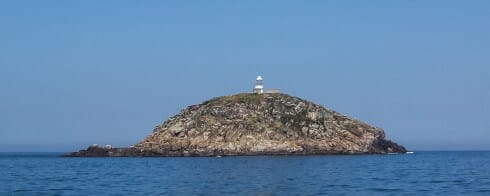

So we were up and away in the dark, reaching into a foul tide in order to pick up the best of the favourable tide through the treacherous bottleneck at the Mull of Kintyre. This is a critical point in the passage—get it right and you’re flying, get it wrong and you may well regret it, especially as the overfalls here are around the worst in the British Isles. But with a moderate northeasterly and the tide under us we charged through the tidal gate and settled down to enjoy the magnificent backdrop of the Glens of Antrim, until the tide turned against us off the Maidens Lighthouse and we slowed down for a long slog into Bangor.

And there, the marina had the ambience of an abandoned shopping mall, and apart from one boat on our pontoon showing signs of life, that was it.

Finishing off the warps, I overheard Lou talking to the good people from the boat opposite, just in time to catch the alarming word ‘gin’, and before we knew it we were sitting in the warm fug of our new friends’ boat sipping ‘mother’s ruin’ and enjoying the craic.

Now Irish hospitality is notoriously warm and generous, but it needs to be treated with respect, otherwise there is an inherent risk of becoming over-refreshed. But a couple of hours later that really didn’t seem to matter any more, and by the time the charming lady skipper and I discovered that we were, in fact, distant relatives, our fate was well and truly sealed. Oh dear. Tomorrow wasn’t going to be fun.

Fortunately a residual sense of self-preservation had kicked in at the last minute, and we dragged ourselves away from the party while we still could, but it was a less than lively crew who staggered on deck the next morning.

First light again to catch the tide for the next leg down to Carlingford Lough. Luckily for us the wind was light, the visibility good and the engine reliable, so despite having to hand steer it could have been a lot worse. Our off watches were spent in peaceful oblivion recovering from the previous night’s revelries, and the hours slipped by until we entered the calm of the Lough before coming to anchor just west of the marina.

No need for knock out drops that night though, although my dreams were beginning to become infected with doubt. This was all going far too well. The weather too good, tidal gates made on time, no mechanical problems so far—the gods must have something awful in store for us. Lou remained cheerfully dismissive of this pathetic lack of moral fibre and merely tugged back at the duvet.

Stick To Daylight If You’ve Got Any Sense

The tides weren’t perfect for exiting the sluice gate at the entrance to the Lough at first light, so there was no need for a dawn departure, fine except that it did mean that the next leg would not be the longest, taking us only as far as Dublin Bay.

Not that I minded—night sailing along the east coast of Ireland is an acquired taste, to say the least. Stay inside the banks that lie parallel to the coast to cheat the tide and there’s fishing gear everywhere, with long floating ropes just waiting to snag your prop. Outside the banks you’re into the worst of the tide and mixing it up with the fishing fleet and the shipping. Best to do it by day.

And still the weather held…

Dun Laoghaire sounds lovely, but out of season it has a beauty that’s hard to discern. The marina is just a giant boat park, and at that time of year the staff go home at 8 o’clock, something we would have appreciated knowing before we entered. No matter, except that the morrow’s 8 am arrival of the same staff would delay our departure, thus ensuring we wouldn’t make it past Arklow before nightfall.

And the first signs of a change in the weather were beginning to appear on the synoptic charts so we knew we needed to keep the pedal down if we were to get across the open Atlantic down to Cornwall and home in good shape.

I Think I’ve Been Here Before…

Entering a desolate, deserted Arklow, my thoughts were way ahead, thinking of the potential for entertainment that awaited us at the shallow, vicious tidal gate at the Tusker Rock off the southeast corner of Ireland.

My mind kept going back fifteen years to a ghastly night there during my first week as mate aboard a big gaffer. Arriving from the south too far to the west just as the tide turned against us was our first mistake and, with a stiffening force-6 up our transom, we were soon in a very interesting place indeed.

Time to hand some sail, but Murphy himself was aboard and caused the downhaul of the jib to part. So for the next hour the skipper and I found ourselves out on the end of the bowsprit alternately fighting the unyielding flax canvas and hanging on by our eyelids as she pitched into the short, steep, freezing seas, dunking us like a couple of teabags. Even in the warmth of the bunk I shuddered at the memory of it—Lou simply murmured, ‘calm down—it’ll be OK’.

It Couldn’t Be Worse Than That—Could It?

OK? Well maybe once I’ve woken up and this next lot’s behind us. Up onto the frozen deck in the dark and straight onto my backside, the first part of that requirement came immediately, painfully true.

The voice of the forecaster had now risen half an octave, as if to say go, go now, idiots. Perhaps 36 hours of moderate northeasterlies before the wind would freshen, albeit from the same direction, and then fog with it. Could we make it in time? Tough call.

We discussed the odds, and agreed that fortune favours the brave, and that if we didn’t go we might be stuck in freezing Arklow for a week—that clinched it. So out we went and as evening approached we slipped out between Carnsore Point and the Tusker Rock into the Atlantic, and for Lou the first solo night watch of her cruising life.

First Night at Sea

I’m sure we all remember our first solo night watch. In my case, it came when I was a youngster determined to push the limits in my first cruising boat, careering down the English Channel towards the mythical Isles of Scilly from our homeport in Devon. A strong, gusty east wind and big seas set the little boat reeling westward as if on some demented fairground ride, while the roar of the sea, the shocking white of the occasional breaking wave and the intoxicating reel of stars made me want to shout with exhilaration and recall a forgotten prayer simultaneously.

So handing over the watch to Lou as the night set in was tough, in the sense that I really didn’t know what to say. Say too much and you can have the opposite effect to the one you seek—clumsy reassurance generating concern rather than solace—so I kept my counsel. Anyway, if she was nervous, it certainly didn’t show. But I hardly slept a wink, fighting the urge to come on deck and check she was OK—and perhaps spoil it for her.

Those three hours seemed an eternity to me, let alone her. But when I appeared at the hatch with a cup of coffee at hand-over time, she said ‘boy, am I glad to see you!’ encompassing in that simple statement the whole gamut of human emotions. And I felt the same.

By now we were well on our way, in ideal conditions. Steering was a pleasure, as Forever Changes loved conditions like these and she really had the bit between her teeth.

But our friend the forecaster had now begun to sound increasingly miserable, and with good reason. Northeasterly 4-5, increasing 6-7, perhaps gale 8 later, drizzle and fog patches—deep joy. But we were out here now, so we just had to crack on, bound for the Isles of Scilly.

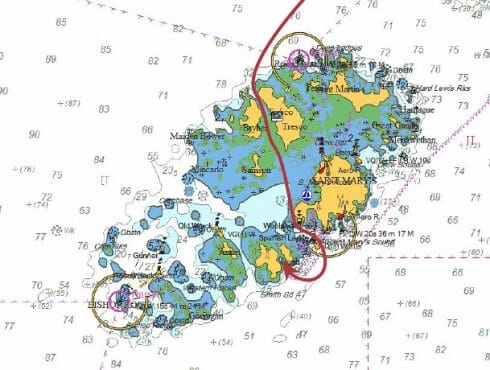

First light and the visibility had already closed in, while the wind and sea were building steadily. Finally a flicker of light out in the grey of the dawn—Round Island Light, dead ahead. Latching our eyes onto it in case it disappeared, we altered course to the west to enter the islands via New Grimsby Sound, the channel between the islands of Tresco and Bryher.

The tides around the islands are strong and unpredictable, and often stymie your efforts to reach a safe haven quickly when you need to. Knowing that the best anchorage with such a forecast lay on the far side of the islands, in the Cove between St Agnes and Gugh, we knew that it would pay to get into the islands as soon as possible where the tidal streams are weaker and then sort ourselves out.

As we slipped into the Sound the weather closed in again, and the drizzle became more solid. It felt raw and bleak, a far cry from summer days in this lovely place. The tide was perfect for us to cross the shallow Tresco flats into the Road before homing in on the doleful clang of the bell buoy at the Spanish Ledges, then out around the corner into the familiar safety of the Cove.

Not a boat in sight—the islands looked and felt dead in the gathering gloom. Out in the murk, the Bishop Rock Lighthouse foghorn began to low gloomily. We’d arrived not a moment too late.

Down went the hook with plenty of chain, right up in the best of the shelter, no other boats about to beat us to the best spot this time. As she lay quietly to the rising wind we felt as safe as if we had been in a landlocked marina, not out here in this precarious little cleft in the rocks surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean.

As we settled into the cozy comfort of our bunk, Lou said, ‘that was great, wasn’t it?’—and I had to agree.

I sometimes think that cruising most closely resembles a cold, damp game of snakes and ladders, where ‘the best of players will make something of the worst of throws’. It seemed that this time we’d thrown well and got a good result—we had passed the first big, tough test, and the best was yet to come.

Further Reading

All of this took place some years ago. Since then Colin and Lou had an Ovni 435 built and have cruised extensively, including an Atlantic crossing to Brazil. You can learn more in two of Colin’s Online Books:

It’s great to see you treating this trip as a test of whether you can live aboard together. My wife and I are currently doing just this, and we’re also in the Irish Sea right now. We decided that if we can make it around the UK, then the rest of the world is ours for exploring. We’re getting on really well too and are loving every minute of it. We’re now waiting for a northerly to start up this weekend and we’ll leave southern Ireland for the Scilly Isles.

Hi Steve

good to hear you’ve come up with the same plan – great minds think alike?

And, you’re right – if you can make it round Britain OK, you should be good to go.

Looks like you’re going to get the northerlies OK – hope you enjoy the Isles of Scilly.

Best wishes

Colin

Something like this?

https://www.google.com/maps/ms?msid=211394638864906580037.0004e49e651196fbf177c&msa=0&ll=55.435247,-4.910889&spn=3.553413,5.410767

Hi Andrew

Sorry I missed this first time around – yes, that’s our route exactly.

What a great resource!

Best wishes

Colin

Colin,

Good article and a wonderful and complex subject.

Ginger & I had sailed the east coast of the US, Maine to Bermuda, for 25 years with 3 children working our way up to 4-5 weeks a year on board and most weekends. We considered that we knew what we were doing, boating and relationship wise, but the first year, living full time on board, having given up occupations, home etc. was very hard, surprisingly hard, quite wonderful, but a lot of work.

A couple, experienced sailors, we became friendly with down in Central America tell a story that nails a place where most cruising couples end up at some point in their boating career. Still working, they bought the boat of their dreams in Hawaii and, on a schedule, picked it up and headed east. Five days of beating to wind later she said to her husband: “I hate this f—g boat, I hate this f—g ocean, and, if at all possible, I hate you more today than I did yesterday.” (Best done with a southern drawl.) Then she went on watch and they stayed together on their new boat to relate this story to us years later.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick

It always seems that the first year is the hardest, shaking off the old way of life and adapting to the new. So many mixed emotions….

And beating to windward for days on end is enough to test the most determined couple – I think your friends behaviour sounds quite restrained myself!

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

I really like these more ‘human’ articles on AAC – don’t get me wrong the technical ones are also good -but in the end, people is what it’s all about!

I really think this idea of ‘test driving’ a sailing relationship is fundamentally important. For me it showed over a period of time that I needed to modify my sailing aspirations, and with Hazel’s blessing spend some time with gentler sailing as a family, and then do more ‘adventurous’ sailing apart from her; which is of course a compromise.

My point though, is that the important bit is both being true to what works as individuals and then make it work as a couple.

On a separate note, I’m glad that you have managed to access the right side of Irish hospitality; my in laws are strict Baptist…. so G&T with them is a somewhat different God and Tea… and having not yet seen part II my guess would be that you had the better evening – but I would be (sadly) more ready for a 5am start 🙂

paul

Hi Paul

compromise is what it’s all about, and unless you test the limits it’s hard to know where the ‘balance point’ is. Better to find out now and then live with it, than risk everything somewhere down the line.

We did have a great evening, and the only time the name of the Lord was invoked was the next morning – when I woke up…..

Best wishes

Colin

Bonjour

Un long voyage en bateau est le meilleur test d entente et de connaissance de chacun, ce en quoi ce récit détaillé est intéressant

Bon vent et longue vie a ces navigateurs

Ulysse qui navigue depuis 30 ans avec son epouse

Merci Daniel

Je suis complètement d’accord – c’est le mieux ecole pour l’entente cordiale dans un marriage – et le preuve c’est votre trente ans d’expérience!

Colin

Colin, in the rush to perfect gadgets, gear and techniques, the cruising couple’s dynamic (or its absence) can be ignored. Panama is said to be the place where freshly refitted boats go to die along with the marriages of couples who did not know enough about themselves at sea…before they ran off to sea.

One of the best books on this that I ever read was “Two on a Boat” by Gwenyth Lewis. I reviewed it here three years ago:

http://volumesofsalt.blogspot.ca/2010/12/capturing-cruising-couple-dynamic.html

Hi Marc

You’re absolutely right in my view. If people spent a fraction of the time working up their mutually dependent skills that they do on worrying over electronics or kit there’s be a lot more happy couples out there. It’s a great pity that for some people the dream goes sour, and whilst a percentage of failures is bound to be expected, I’ve met several cases where it could so easily be avoided. And although these posts treated this in a light-hearted manner, nonetheless there’s a strong element of truth there too.

I read the book you refer to when it came out, and liked it a lot, too. A very simple, humble story told with insight and humour – good reading, and a nice antidote to some of the hairy chested stuff that graces the shelves of bookstores.

Best wishes

Colin

As part of our familial run-up to cutting the dock lines, I’ve made a point of getting my wife to “work the boat” solo as often as possible (it’s not laziness, really!). We’ve also made separate ocean deliveries as crew, partly for the somewhat morbid reason that if things went bad, our young son wouldn’t be left an orphan, but also because it breaks habitual behaviour to learn in the absence of one’s spouse, and because we effectively get twice the experience for our cost of plane ticket and time spent away from home.

The reality of couples sailing isn’t widely acknowledged in that it’s as much two people solo sailing the same boat as it is “couples” or “family” sailing. If we are on passage and I’m standing watch, my safety in my off-watch to come absolutely relies on me providing the most restful experience I can while she’s tucked away in her berth.

It also depends on us having pretty equivalent deck skills. Certainly, she’s the ship’s doctor and I’m the engine and electrics guy by experience and temperament, but we both have the same CN and radio skills (and certifications) and we can both read the weather in a timely enough fashion to tuck in a reef without having to wake each other up.

And yes, I’m probably the better cook. I don’t mind galley work.

This is not, alas, always the case. Too many cruising couples are living the husband’s dream (usually), with the wife along as a reluctant cook, who comes to resent every minute spent inside the junior bachelor apartment that never stops moving and has inadequate plumbing.

The results can be seen at any yacht club bar: a man alone, getting pissed and trying to convince you to buy his over-equipped cruiser.

Cruising has to be a joint venture, I think. Either that or take the sea hermit route.

Marc,

I couldn’t agree more with your thoughts and insights above.

It’s a shame that more solo male sailors can’t get to the stage where they commit to enjoying sailing solo, or find a- n – other to regularly sail with them. It’s also a shame that so much focus us put on boat toys and tweaking them instead of just being out there doing what it’s all about, whilst enjoying being with the people you are with.

Your off watch point is why Hazel and I err towards long day sails with me having a snooze during the middle of the day at a suitable time… and do not complain if woken.

By contrast, when doing my charters I have Mel who is training towards her yacht master and keen to learn all aspects of cruising and sailing; and even better is 20 years younger than I and very happy, as I am, with her less keen on sailing partner.

paul

Hi Marc,

I don’t agree with your comment or the common advice that both partners should be able to handle the boat with equal competence before going cruising. The idea is seductive, but in cases where, as is very common, one partner has sailed all their life and the other is new to it, such an expectation is simply setting the less experienced partner up to fail. No amount of training or practice will give a person that innate feel for a boat that sailing from childhood provides.

Rather, I like to see each member of a couple concentrating on their own areas of competence so that each can get a sense of mastery and the resulting satisfaction as soon as possible. After that, the less experienced partner can chip away at deck skills over time without the pressure of having to achieve a certain task list by departure date.

Phyllis has written more, and eloquently, about this issue.

Paul: Glad you liked the post and we all have to make adjustments when it comes to enthusiasms: some partners will often prefer the sailing life more than others.

John: Perhaps I should have said “equivalent” to “equal”. My wife had a sailing father who actually designed and built a few boats in the ’70s and ’80s. I had a WWII Merchant Navy father who didn’t venture out in more than a rowboat until I bought my first sailboat in 1999. So there is a discrepancy in terms of myself having more sea miles, helm time and familiarity with the terms, versus my wife who can move like a cat on the foredeck (from doing so as a child) and who is careful yet fearless in all weathers.

These attributes are complementary, not setting up for failure, in my view. The point of making separate delivery trips was so there was no excuse for the (allegedly) “more experienced sailor” to just do the jobs needed, and therefore the person on a strange boat is taken a little out of their comfort zone. Occasionally, I find my wife making a knot I didn’t know she knew, and I realize she learned it elsewhere. That’s actually a good feeling.

But I would respectfully say that there is a minimum skill set that, by education, trial runs or deliveries, should be attained before cruising beyond coastal. It needn’t mean absolute parity, but when someone is off-watch and getting absolutely required sleep, short of imminent danger or an unforeseen weather event, the person on watch is effectively and functionally in charge, and should not be so lacking in knowledge that they can’t trim, correct course, keep a log, keep a watch and stay on the boat.

Conversely, there has to be an acknowledgement that the off-watch person might have to jump into foulies and deal with situations pre-arranged to be worthy of “all hands”, like a rapid weather change, an equipment failure, or some other mid-level crisis. I don’t expect solo heroics, and neither does she.

If I didn’t have that confidence that my wife could pull that off, I could never sleep soundly on passage…and I usually do.

John (and Phyllis): I read Phyllis’s piece, and strangely…I’m more like her than John. I never even took shop (the girls were in drama class, after all), and have had huge hurdles acquiring the skill set (with an aging body and brain) required to run a complex boat.

So I get that part very well. Because I’m not, and will never be, a “natural”, I have to work from lists, mental and actual. My wife just says “that thing needed pulling and I seized it this way”. While her terminology has improved…she just *knows* how to do a lot of things…even if her lack of height and leverage lead to sailorly commentary.

But I still think that her taking a diesel course while I took a marine first aid course (in other words, deliberately working each others’ turf) was simple prudent seamanship. Phyllis, by contrast, got thrown in very much at the deep end, if her first trip was Bermuda to Maine…cripes, that’s the sort of delivery I’ve had to work up to!

Hi Marc,

Many good point in your comments. However, the key point I’m trying to impart here is that different people have different needs and strengths and therefor trying to apply rules to all couples, as the yachting magazines are so fond of doing, like each person must be able to hand, reef, dock, anchor, and stear, before you can go anywhere sets up many couples to fail.

Over the years I have taken many people to sea who had minimal sailing skills, and they, I, and the boat have made out just fine. The point being that attitude, enthusiasm, conscientiousness, and consideration for the boat and fellow crew are way more important that specific skills.

I can teach anyone to stand a watch competently in 48 hours, but I can’t impart the essential qualities that I listed above.

Once again, Phyllis has some great tips for those new to offshore sailing here.

Hi

I just ordered a copy of said book, actually Hazel did, and when I asked, in passing, how much it had cost, she replied £1.46 (from Amazon) ….. second hand? …. no NEW! ; so how much do the authors get????. There is something really wrong with the publishing world!

paul

Paul, Marc

Much sensible advice from you both. Finding what works for you both parties is what matters, and there’s no unique formula for that. But starting from a position of mutual support and skills is a very good place to start.

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

Perfectly put, I think.

Many years ago I interviewed a British sailor who had circumnavigated solo south of the five capes. He said the Irish Sea was the worst body of water he’d ever experienced.