There are few more soul-destroying or pointless pastimes than wishing the weather would get better. Constantly scanning all of the available weather information (GRIBs, web, SSB, etc.), looking for the faintest glimmer of an improvement, it can easily get to you.

Too much information is almost worse than too little, and can badly delay or even de-rail your plans if you let it get on top of you. You can end up only seeing the most negative information (Gusting Force 8 at 10 a.m. on Tuesday! Waves at 6 seconds!) and not the bigger picture, which might actually be more benign.

Worrying and waiting until everything is absolutely perfect is a loser’s game, that saps confidence and can ultimately lead to missed opportunities for some great passagemaking.

Now, nobody wants to go out and get a battering (unless they have got latent masochistic tendencies) but if you’ve got a good, solid, well maintained boat and you’ve seen this stuff before, you’re in good shape. If so, you know that while you might not like it when the weather is at its worst, you also know that the boat will look after you.

Knowing that it’s doable within the skills of the crew is perhaps the more important factor here, and that’s where pushing yourselves a little to make passages when the forecast is less than perfect can be a good training regime, building confidence and teamwork to new heights.

“Time spent in reconnaissance is seldom wasted.”*

With an open water passage coming, we’ll start to look at the weather at least a week beforehand, to begin to get a ‘feel’ for present and future patterns. We don’t expect much from this beyond a rough guide.

A few days before we hope to depart we’ll begin to look in more depth, especially at GRIBs, to get a sense of the bigger picture of highs and lows, and how they might develop and influence each other.

We find web-based sites such as Passageweather and Windguru very useful at this stage, containing a lot of information in an accessible format.

Once we’ve settled on a likely departure date, we’ll check developments a couple of times a day to assess the stability of the pattern and make sure that no real nasties like secondary lows are lurking in the wings.

Once the moment to go arrives and all is looking good, we’ll get as much last minute information as possible and then head out, at which point we reckon that we can probably rely on what information we have for the next 48 hours.

If the passage is going to be longer than that, then we accept that to a greater or lesser degree we’re in the realm of no more than informed guesswork weather-wise, and that what comes next, comes next, and we’ll deal with it accordingly.

We often plan a route on a laptop, using Open CPN software, and overlay GRIB data on to the charts together with possible routes, waypoints and distances to safe havens. We then save the pages for later reference (or in case the plotter goes down). It makes for a useful, quick review of likely conditions and escape routes.

What’s the likely wind direction?

This is a major factor. It’s one thing to head off with a strong following breeze, quite another to slam head on into the same wind from ahead—beating into 25 knots will mean an apparent wind approaching gale force over the deck, whilst the same wind over the stern will feel like an easily manageable Force 5 (15-21 knots).

Going upwind in those conditions will be wet, uncomfortable and hard on the boat and crew. We wouldn’t willingly depart in such conditions unless we had to, and even then we’d try to wait for a lull or wind shift to clear the land, where most problems will manifest themselves due to shipping, fishing gear, shallow water, strong currents and the wind effects off headlands.

More or less wind?

We’d always choose a forecast with more wind than less (within reason). It’s a fact that overall you’ll spend more time in light winds than strong winds when ocean passagemaking, and it’s a shame to waste a fair wind, even if there’s a little more of it than you’d normally sail with.

Reef down, sail conservatively, and don’t miss the chance to build your confidence and skills.

When reading web forecasts:

- Remember that they are smoothed and that gusts can be much higher.

- The choice of model employed to interpret the same raw data can present those data very differently.

- Average wind speeds in open water nearly always seem (to us) to be higher than forecast.

- Look at the associated weather—some sources don’t give much detail—like thunderstorms, for example. Use a range of sources.

- Don’t use them in isolation, use them in conjunction with charts and pilot books to look for potential land effects that might generate adverse conditions and currents that can drastically alter sea state, as these can often affect progress far out to sea.

An Actual Passage On Pèlerin

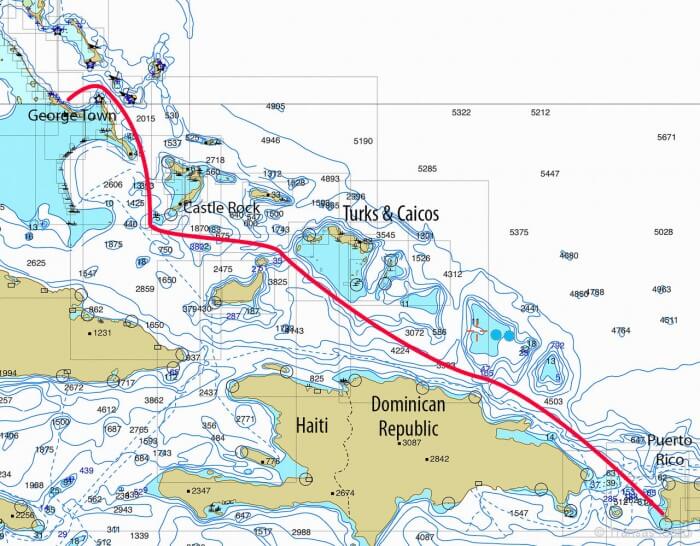

Having spent many days at Fajardo, at the eastern end of Puerto Rico, exploring ashore, we were champing at the bit to set off for the Bahamas.

Our original plan had been to head around the north of the island with the Turks and Caicos as a first stop, but with the forecast for the week showing a constant procession of winds of Force 6 to 7 (21-33 knots), that didn’t look like a comfortable option, so we decided to head along the south coast, daysailing between anchorages.

We weren’t delayed enough that we had to go, so we’d get to see some more of an island we liked, we were still going in the right direction, and hopefully by the end of the week the weather would improve. We did the sensible thing and rolled with the punches.

By the time we reached the western end of Puerto Rico, the forecast was far more favourable, with east and southeast winds of Force 5 to 6 (15-27 knots) predicted for the next few days before dropping lighter later. Perfect conditions for fast passagemaking, and we set about getting ready to go and clearing out.

Our Passage Plan

We followed our usual practice and sketched out a passage plan, based on weather conditions, breakdowns, crew comfort and fatigue.

Departing from Puerto Real on the west coast of Puerto Rico, we knew we’d have at least a few hours of motoring in the wind shadow of the island before the wind would fill in.

Ports of Refuge

If we had any problems after that, the first possible port of refuge would be Semana in the Dominican Republic (c. 30 hours), followed by Luperon (c. 48 hours), then Grand Turk or Providenciales in the Turks and Caicos (c. 72 hours). If we were going well and not too tired, we’d keep going to Georgetown in the Bahamas (c. 96 hours).

The first three options were less than ideal for a number of reasons:

- Semana is in a large bay open to the east, and looked like a hard place to get back out of in the prevailing winds and conditions;

- Luperon seemed to have a permanent strong onshore wind feature, and that didn’t appeal;

- None of the easily accessible anchorages in the Turks and Caicos looked very sheltered in the conditions we expected, although with our shallow draft we knew we’d get in somewhere safe, even if not comfortable.

So all of them were simply ports of refuge, not useful tactical stops.

Day one

Up at first light and out into the Mona Passage, flat calm and no wind, so a good time to do our washing! Gradually, the wind filled in from the northeast, bending around the west end of Puerto Rico and accelerating down the Mona Passage. Full sail, fast two sail reaching, putting a reef in the main later in the day as the wind continued to increase.

At nightfall, as always, we reefed further, putting a reef in the yankee for safety, making life easy for the on watch crew member, and more comfortable for the one sleeping below.

By now the wind was occasionally reaching Force 5 (15-21 knots) over the quarter, so boat speed was still high, with precise steering control via the Windpilot.

During the night the wind got up further at times, necessitating further reefing to keep everything well within safe and comfortable parameters.

Day two

Began with perfect conditions, with the wind now a steady east Force 5 (15-21 knots), occasionally 6 (21-27 knots), over the quarter and 2 m following seas. Two reefs in the main and one in the yankee, as it was now daylight.

With a further increase in the wind expected later in the day, together with a wind shift more to the southeast that would bring the wind round almost dead over the stern, we expected to be poling out well before nightfall, and did so just before the start of watches at 1800.

By now the wind was an altogether more robust Force 6, and the sea had got up, too. With night falling we had two reefs in the main and with the yankee strapped down tight on the pole with two reefs, we were under complete control.

During the night, we had yet a little more wind and took a third reef in the main and also the yankee to keep things smooth and calm, which proved the right move when the occasional squall came through.

Day three

Another beautiful morning, and in the daylight we unfurled a little more yankee to keep her trucking along. By now all of the ports of refuge were behind us, having never been given serious thought.

By afternoon we expected to round the southern end of Acklins Island, at which stage we could decide whether to head up into the lee of the island to anchor and clear in at Spring Point, or carry on for a further night to Georgetown.

Approaching Castle Rock, the wind was still around Force 6, so we gybed the yankee and stowed the pole before hardening up on the new course to the north.

As we’d have to motor for 15-odd miles across very shallow banks, sometimes straight into the wind, to reach Simons Point, it wasn’t a hard decision to make to keep going, even though we knew we’d have to slow down to make a dawn arrival at the entrance to Georgetown.

Day four

We steered a conservative distance off Cape Santa Maria to avoid any fishing activity (although we didn’t see any) and turned south around midnight, reaching slowly down to the entrance to Elizabeth Harbour, where we arrived at our waypoint in the early morning light after 96 hours and five minutes on passage.

A Perfect Passage

It was a fantastic sail, one of the very best. Both of us were fresh and had slept well (apart from the first night—and who sleeps well on the first night?). We had cooked and eaten good food throughout the passage.

Total breakages: two telltales on the mainsail that got mangled during reefing.

Three hours motoring in total, just as we left Puerto Rico.

We had covered 636 miles, at an average speed of nearly 6.6 knots, with no real effort on our part.

Maximum wind speed observed was 30 knots during a squall. We hadn’t taken any risks, had taken our chances when required, and Pèlerin and a good forecast had done the rest.

What was in our favour?

Pèlerin positively revels in these downwind conditions. With the centreboard pumped into the up position, she is surefooted, controllable and easy on the helm.

As usual, our Windpilot Pacific performed its magic, but we generally hand steered during the squalls, more as a precaution than a necessity, as the wind was shifting in the squalls.

The only time we used the autopilot was when motoring at the start and late on day three approaching Acklins Island, when a combination of wind and current created a shorter, unruly wave train that had us occasionally surfing, which upsets the vane due to the rapid shifts in apparent wind speed and direction.

We had hardly any shipping or fishing boat activity throughout the passage, which always reduces stress when on watch alone.

Did we push the boat hard?

No, we carried a little more sail by day, but we still sailed the boat well within safe limits at all times. She is such an easily driven boat in any case that it isn’t necessary to hammer her.

We changed gear in tune with the conditions, and weren’t lazy when the wind eased, shaking out reefs when necessary to keep her stable, fast and comfortable.

The average wind speeds were higher than the forecasts, but we’d anticipated that and weren’t surprised or fazed as a result. As always, we used all of the tricks that I recently outlined in my posts on reaching and poling out, to good effect. No heroics, no anxiety, just textbook easy sailing.

When on watch alone we have pre-arranged wind speed parameters according to the sail plan and wind direction.

If the wind speed rises and settles above, say, 20 knots apparent, the watch keeper will call the off watch crew to help put in the reef to suit the new regime.

The only exception to this is in a short squall, when the wind should soon return to normal levels.

We both stick to this religiously and it keeps us safe and sound, and means we can rest better when off watch knowing that the other can be trusted to watch the conditions carefully and call when necessary.

Combine that with precautionary reefing for the night watches, and you have a recipe for safety and sound sleep. Similarly, if the wind drops light, we can power up, perhaps at the change of watch to avoid disturbing the off watch crewmember.

We keep a visual and radar watch by day and night to track squalls, and judge their intensity and whether they are going to hit us, which gives plenty of time to call the off watch crew member if necessary.

What To Watch Out For

I’m a great adherent of Adlard Coles’ dictum that you shouldn’t carry any more sail when going downwind than you would upwind in the same conditions. One of the easiest ways to get into trouble is to keep trucking along downwind as the wind steadily rises without reefing.

It all seems like great fun until suddenly the boat is over the limit and then it’s no fun at all—that’s when accidents can happen. And if someone should go over the side and you’ve way too much canvas up, what then?

Knowing when enough is enough is a vastly underrated skill in any cruising skipper, and is well worth cultivating. Don’t push your luck too far going downwind—you’re cruising, not racing.

Other Thoughts

Choosing to depart with a forecast when there is a little more wind than you’d usually go with is a calculated risk, but in this case it paid off handsomely. Having said that, there’s no doubt that it can go the other way, as has happened to me on a few occasions, but far, far fewer times than when it has panned out well.

We did our best to sail a good boat well, and as a result have even more confidence in our personal abilities, trust in each other and in Pèlerin.

Successful offshore cruising is about expanding our comfort zone and improving our skills constantly.

Exploring our boundaries and pushing our limits within reason makes sense, and has an additional dividend in that the next time we’re out there and get caught out in unexpected bad weather (as we inevitably will), we’ll know that we can trust the boat and we’ve more experience of strong conditions and how to handle them. As a result we should be a better and safer crew.

And the perfect forecast? There’s no such thing, but there are plenty of really good ones that come very close if you learn to handle them!

Thanks for a good accounting. Timing the weather as a cruiser is like timing the market as an investor: if you wait for the optimum point, you’ll never get anywhere! A well-found boat with conservative habits, however, can deal with the vast majority of weather scenarios and can even profit by them in terms of miles made good.

Great article, much good info. Like to hear more about how to reef main downwind in heavy air.

Hi Brian,

We have a chapter on exactly that complete with many photos, CLICK HERE. Part of our online book Sail Handling Made Easy.

Do you have recommendations for weather models? There are so many.

Hi Aron,

You will find a bunch of information on that, and a lot more besides by clicking here.

I’m also in the throws of an evaluation of Predict Wind, look for a report this summer.

Finally, it’s important to understand the difference between a source and a model. Most of the GRIB sources on the internet are simply repackaging readily available FREE government data and models. Some even charge for that.

You can get the same data for free by using Saildocs, look to the above link for instructions.

Predict wind does have it’s own model, but even there they are using US and Canadian government data to initialize the model.

As to which model. It’s hard to beat the good old US government GFS. Our friends to the south (I’m in Canada) have spent a huge amount developing it and it is constantly being truth tested and improved.

Thanks for the excellent article. Sounds like all went well, which is usually what happens when things are well planned and maintained. I have fruitlessly searched all of the photos looking for jack lines and your tether when you are sitting on the fore deck. Do you not use them or are they just not obvious in these photos?

Thanks

Stan

Hi Stan

you can only just see the jackline below my feet, under the red line. I am always clipped on in such conditions!

We use a double thickness nylon strap, well tensioned, that runs from the cockpit to the bow cleats, so there’s no excuse not to. And we use the same Spinlock lifejackets and harnesses that John and Phyllis use – not perfect, but the best there is, currently.

Thanks for the compliment re the passage. We maintain everything structural and mechanical very carefully, the cosmetics we try to keep on top of!

Best wishes

Colin

As always enjoyed your post. You probably already know of it but an excellent free site for early planning of a passage is https://www.windyty.com/. They are continuing to add new features as well. Can quickly check to see if passage you are considering makes any sense any time soon.

Hi Bruce

no, that’s a new one to me – looks very interesting and I’ll have a good play with it to check out what it offers – many thanks for bringing it to our attention.

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

Lovely article and sounds like a delicious passage.

You wrote:

At nightfall, as always, we reefed further, putting a reef in the yankee for safety, making life easy for the on watch crew member, and more comfortable for the one sleeping below.

As mentioned before in these pages, I like to keep Alchemy moving at about 75-80% of her capacity. We have never reefed down at night as a habit, only in the face of a forecast for increasing winds or squally conditions that might take us by surprise. I am aware that many experienced sailors do this as protocol. You mentioned the yankee, but many reef the main as a habit.

A couple of comments:

I am not sure that reefing down always makes things more comfortable if you are sailing at the 75-80% level I would recommend for offshore passages. I certainly am clear that being under-canvassed often allows the waves to dominate and can make for a mighty uncomfortable boat: much more uncomfortable than continuing to sail under reasonable canvas.

I do know that some I have talked to reef their main at night as, on their vessel, it takes 2 to reef and this protects the asleep crew from waking up and gearing up.

It is also slower and if you are spending 1/3 to ½ of your passage under-canvassed, it will take longer. Longer passages mean more time for bad weather to target you.

So, reflecting the above, I would not recommend knee jerk nightly reefing of main and yankee if the main and jib can be safely, quickly, and effectively reefed single-handed.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick

we tend to reef the main at night in anything more than moderate winds for the very reasons you point out. One, it’s easier to reef with both hands on deck, although it’s still possible to do it on your own, except that it takes more time and is likely to disturb the off-watch crew. And it means that if the wind gets up a little more than required there’s no need to wake up the sleeper below. Reefing the yankee is easy, as is shaking a reef out, and we use that like a throttle much of the time.

Perhaps I ought to have described it better that we push the boat a little harder by day. We are easily within your 80% band at night, and in any case our boat is so easily driven and stable downwind that reefing the main often has little effect other than to just take the ‘edge’ off progress. Slowing this boat down is harder than on any boat I’ve sailed before!

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin and Dick,

I suspect the difference we are seeing here is one of background. We too tend to carry less sail at night than we do in the day, even though it is very easy to reef our boat, both main and headsails.

Having said that, this does not mean we are dramatically under-canvased at night, since we agree with Dick (and I suspect Colin) that being so is very uncomfortable.

Rather, reefing at dusk is driven by the fact that when I am up and about during the day the boat is often being driven harder than 80%. This is a result of my some 40 years of racing under sail. I just can’t help myself and getting the very best out of he boat is a lot of the enjoyment I get out of sailing.

But I also understand that as soon as I hit the sack it is better to tone things down a bit, hence reefing at dusk.

I’m going to guess that Colin’s racing background manifests in the same way.

Hi Colin, Understood and agreed. My only point, I guess put simply, is that if reefing is easy and done single handed-ly, then there is less reason to reef down at night as common practice. Dick

Hi Colin & John,

And I am quite clear that I have a robust competitive side which, by and large, has not manifested itself sailing but has seen full expression on ice hockey rinks. Dick

Hi Dick, John

Dick, you’re absolutely right, easy reefing is key, but if we can avoid it while I’m off watch, then all to the good! Because I’ll wake up the second I hear the winch turning…..

And like John, I tend to drive the boat a little harder by day, then ease off the pedal a little by night – nothing drastic, as our daily averages show. And a boat left wallowing after a blow when you could get her back on her feet is an abomination!

But – I hate seeing a badly trimmed sail – I’ll dig out the spinnaker or LWG at the slightest opportunity, and try always to sail the boat at her best.

It’s a very long time since my last big race (Fastnet ’97) but the competitive instinct still won’t let me rest. But I do try to keep it under control because Lou says it makes me start swearing……

Best wishes

Colin

Hi Colin,

Lou and Phyllis should form a club. Phyllis says that when she hears the constant scream of winch pawls she knows my “Maniacal Racing Skipper” side has come to the fore. Like you, my last race was in the mid-nineties but the drive is still there.